National Portrait Gallery -London

10 October 2024 – 19 January 2025

Study for Self-Portrait, 1963 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales;

Three Studies of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1967 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin;

Self-Portrait, 1987 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection, NYC.

Francis Bacon has long been considered one of the most outstanding painters of the twentiethcentury. Best known as a figurative artist, his work transforms the appearance of his subjects through an extraordinary use of paint. Francis Bacon: Human Presence (10 October 2024 – 19 January 2025) will be the National Portrait Gallery’s first exhibition to focus on the work of this important artist, and will explore Bacon’s deep and complex engagement with portraiture – from his responses to portraits by earlier artists, to large-scale triptychs memorialising lost lovers.

Featuring more than 50 works from private and public collections around the world, in addition to photographs of the artist, Francis Bacon: Human Presence will be organised thematically and chronologically, starting with works made in the late 1940s and closing with portraits painted at the end of his life, one of which remained unfinished on an easel in his studio.

Through five key phases – Portraits Emerge, Beyond Appearance, Painting from the Masters, Self Portraits, and Friends and Lovers – the exhibition will chart the evolution of Bacon’s practice, exploring how he both embraced and challenged the traditional definitions of portraiture.

Bacon’s early works feature disconcerting figures, screaming or pained, as the artist explored how to depict humanity in a post-war world.

The exhibition will begin by introducing viewers to a selection of these early paintings, including Head VI (1949) and Study of the Human Head, (1953) works that depict anonymous male subjects. Both bear all of the visual conventions of formal portraiture. The sitters are presented in a traditional three-quarter-length format against dark backgrounds. In the case of Head VI, the figure is trapped within a transparent cage, while Study of the Human Head peers through striations and appears X-rayed, disconcertingly revealing the sitter’s skull and teeth. Bacon’s early work destabilised and the traditional understanding of portraits of powerful and successful men.

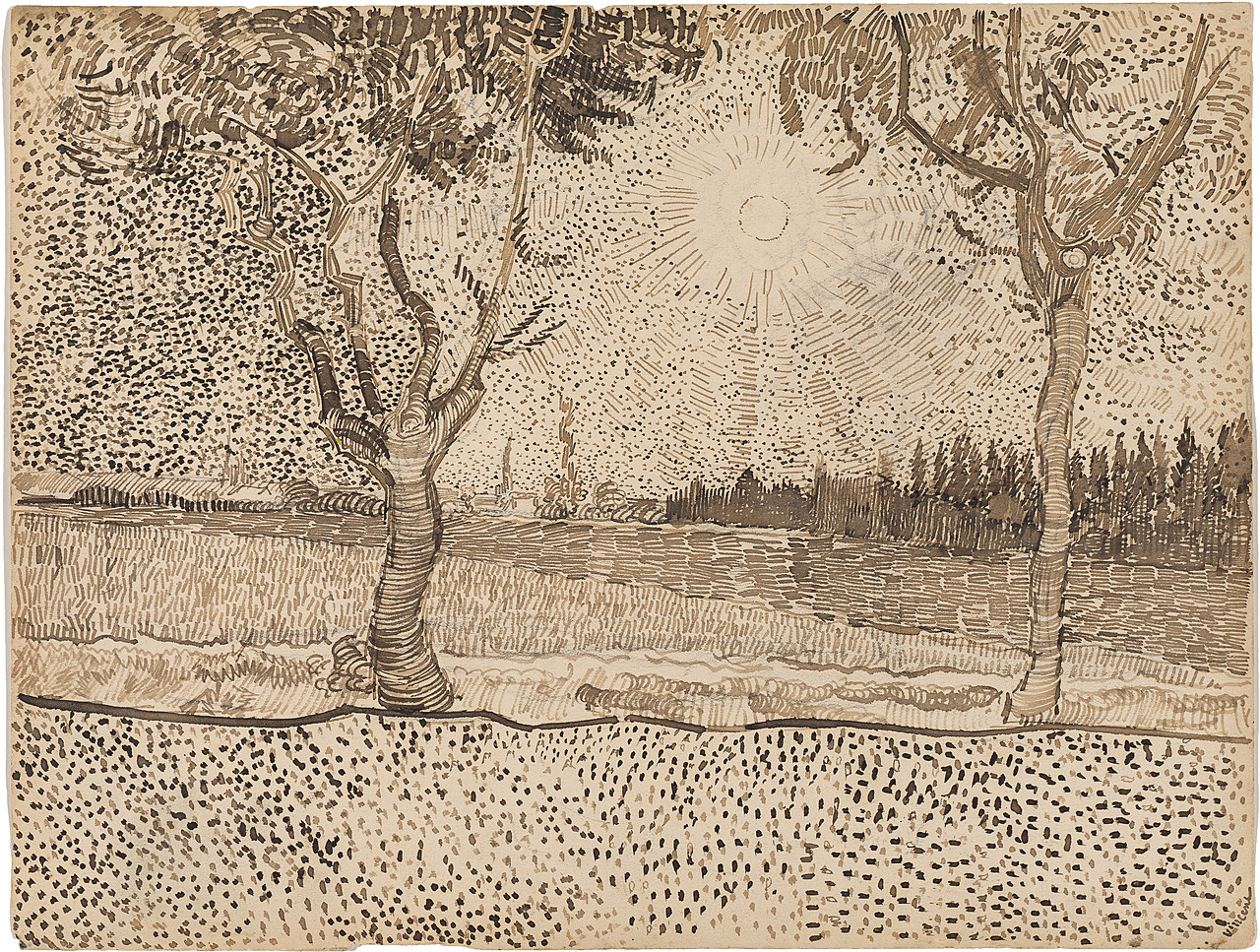

While he never saw

Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X (1649−50) or

Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888) in person,

these paintings became great sources of inspiration to Bacon. From books and torn-out references that adorned his studio floor, he reimagined elements of each painting throughout his career, paying homage whilst challenging assumptions of what a portrait was and could be. Bacon’s interest in Van Gogh saw him move away from the creation of dark, monochromatic images, opting to introduce colour, which would characterise his future work.

Study for a Pope I, 1961 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage. Photo: Sotheby's. c/o Cingilli Collection;

Homage to Van Gogh, 1960 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2024. Gothenburg Museum of Art.

By the mid 1950s, Bacon had moved away from painting screaming figures, but continued to paint ambiguous and unsettling images. Choosing – for the first time – to paint from life, he made portraits of his patrons, Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, and his friend and fellow artist, Lucian Freud, displayed in a section of the exhibition called Beyond Appearance. However, Bacon did not overly enjoy the process of painting from life, which he found to be inhibiting. While he valued qualities of immediacy in the application of paint, Bacon began to frequently distance himself from his subjects in the studio, choosing instead to paint from photographs and memory. This approach allowed him the freedom to ‘distort’ and protect his sitters from any perceived ‘injury’ that he knew he could inflict through his interpretation. Gifted a model of an 1823 life-mask of the poet and artist William Blake, bought from the National Portrait Gallery’s Shop, Bacon also painted a portrait based on this historic object, which fascinated him.

Another ‘Master’ revered by Bacon was Rembrandt, who he admired for his ‘anti-illustrational’ painting style. Bacon studied the brushstrokes that made

Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Beret (1659) while staying in France, and coveted several printed reproductions of the portrait in his London-based studio. Displayed as part of the Painting from the Masters, the National Portrait Gallery exhibition will provide an opportunity to see Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Beret alongside Bacon’s own work, presented as a key painting in his development as an artist.

Like Rembrandt, Bacon returned to self-portraiture throughout his career, painting himself over 50 times during the decades of his life, from small single heads to full-lengths and large triptychs.

Other artists were also drawn to depict Bacon, particularly photographers, for whom he sat throughout his career. The exhibition includes photographic portraits and film of Bacon by some of the century’s leading photographers, including Cecil Beaton, Arnold Newman, Bill Brandt and Mayotte Magnus.

Some of Bacon’s most poignant and introspective self-portraits were undertaken shortly after the deaths of the people closest to him. When his long-term partner Peter Lacy died in 1962, Bacon responded with a small triptych of portraits that memorialised their relationship. A decade later, Bacon lost his lover George Dyer, another potent presence in so many of his paintings. Dyer’s death seems to have compelled Bacon to make a remarkable group of self-portraits, including Self-Portrait, 1973 (1973), which – capturing his grief and isolation – became a way to reckon with his own mortality.

Head of Boy, 1960 by Francis Bacon; © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection; NPG x13707,

Self-Portrait, 1973, 1973 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection; NPG x138805,

As Bacon’s work evolved in the 1960s, his portraits became more personal and focused on a select coterie of sitters. At the heart of Francis Bacon: Human Presence are the artist’s paintings of friends and lovers, who inspired him throughout his life. Transcending likeness, Bacon’s portraits represent some of his closest relationships – including his partner, Peter Lacy; his lover, George Dyer; his partner in later life, John Edwards; his friend, Henrietta Moraes; the founder of the Colony Club, Muriel Belcher; and his friends and fellow artists, Lucian Freud and Isabel Rawsthorne. These clusters of portraits allude to Bacon’s biography – his sociability and tumultuous relationships – but also speak to his acute sensitivity to despair, grief and pain.

While Bacon chose not to paint his sitters from life, he acknowledged that he could not paint them unless he knew them very well. These paintings are perhaps his most intimate and personal, despite their distortion. He preferred to work from photographs, sometimes torn and crumpled, which he had commissioned from the former Vogue photographer, John Deakin, some of which are included in this exhibition.

Portrait of a Man Walking Down Steps, 1972 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection;

Henrietta Moraes, 1966 by Francis Bacon © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection.

“Francis Bacon was deeply engaged with portraiture, challenging long-established expectations of what a portrait should entail. For him, it was the pre-eminent painting genre, capable of expressing what it meant to be human. As one of the greatest British painters of the last century, I’m delighted to bringing so many of Bacon’s works to the National Portrait Gallery for the first time, as we stage London’s first ever exhibition dedicated to his many portraits, fusing image and paint in a truly unique way.”

The exhibition publication Francis Bacon: Human Presence, written by curator Rosie Broadley, will be available from October 2024, with essays by art historian, Richard Calvocoressi; author and art historian, James Hall; art historian and Francis Bacon specialist, Martin Harrison; curator at Tate Britain, Carol Jacobi; archivist of The Estate of Francis Bacon, Sophie Pretorius; associate professor of art history at the University of Birmingham, Dr Gregory Salter; contemporary curator at the National Portrait Gallery, Tanya Bentley; assistant curator of photography at the National Portrait Gallery, Georgia Atienza; and filmmaker and director, John Maybury, whose Love Is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon starred Sir Derek Jacobi, Daniel Craig, and Tilda Swinton.

.jpg!Large.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)