Vancouver Art Gallery

June 24 to October 1, 2017

Claude Monet’s Secret Garden presents thirty-eight paintings spanning the career of one of the most important figures in Western art, focusing on the phenomenal body of work produced in Giverny, a small village in northern France where Monet resided from 1883 to the end of his life in 1926. A creative endeavor in their own right, the gardens that Monet designed and cultivated in Giverny became the central inspiration of his art. Its waterlilies — populated with exotic strains from as far as South America and the Middle East — weeping willows and the famed Japanese bridge endure as some of the most iconic imagery in art.

These audaciously expressive works represent the summation of Monet’s lifelong dialogue with nature that guided him into radically new territories of painting. “Monet’s unique vision, remarkable output and reputation as an intrepid documenter of nature gave full expression to modern life in France. We are proud to bring to Vancouver these pioneering artworks drawn from the unparalleled collection of the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. They trace the arc of a career that spanned over sixty years and that continually overturned conventions to experiment with new ways of rendering the world,” says Gallery Director, Kathleen S. Bartels. “We welcome audiences to immerse themselves in the extraordinary and innovative vision that transformed European painting and paved the way for avant garde modernist art movements in the 20th century.”

Claude Monet’s Secret Garden maps out Monet’s career beginning in the late nineteenth century during his involvement with the Impressionist group of French painters.

Monet’s 1872 painting Impression, Sunrise gave the movement its name and encapsulates its insistence on the primacy of immediate visual perception. The Impressionists cast off historical subject matter and turned to the world around them. Their art gave expression to modern life in France, a country rapidly altered by industrialization and urbanization in their time.

“This sensation of an ever-changing world reverberates through Monet’s art. Together with the other Impressionists, Monet spearheaded a radically new approach to painting,” says Ian M. Thom, Senior Curator – Historical. “In Monet’s art, technical innovations arose from the desire to find a means of expressing his individual perceptions of the world; and above all it was the experience of nature that was the driving catalyst of his painting.”

Claude Monet’s Secret Garden also surveys the diversity of subjects in his art, from the portrayal of modern life in his early figure studies to the inventive treatment of light in his scenes of the Parisian countryside and views of the River Thames. These works attest to Monet’s dedicated experimentation and novel approach to painting, which sought to capture the fleeting appearances and colors conjured by variable light with unique sensitivity.

Collaboratively organized by the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris and the Vancouver Art Gallery, this exhibition is curated by Marianne Mathieu, Deputy Director of the Musée Marmottan Monet, responsible for Collections and Communication; and Ian M. Thom, Senior Curator – Historical at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Outstanding review

Claude Monet

Les Roses, 1925–26

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

Nymphéas, 1903

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

En promenade près d’Argenteuil, 1875

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

Nymphéas, 1916–19

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

Le Train dans la neige. La Locomotive,

1875

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

Londres. Le Parlement. Reflets sur la

Tamise, 1905

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

Sur la plage de Trouville, 1870–71

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

Claude Monet

Glycines, 1919–21

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo: © Bridgeman Giraudon/Press

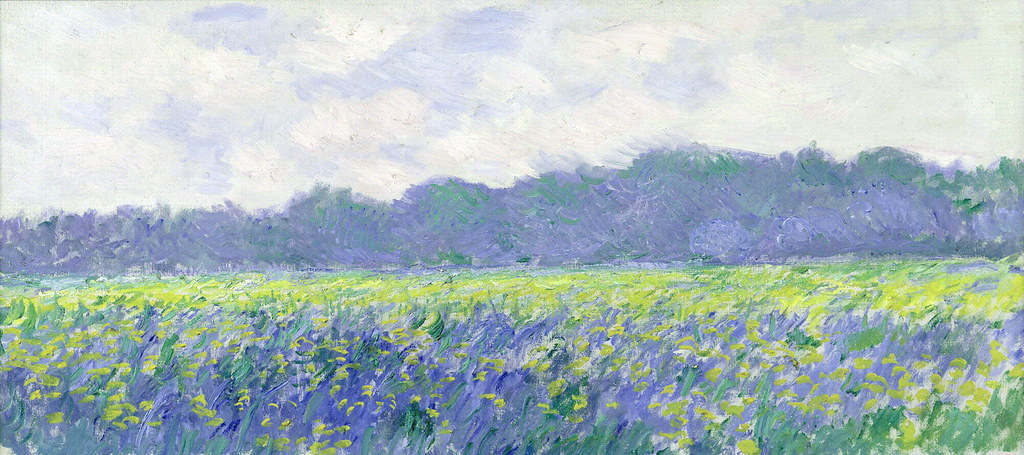

Claude Monet

Champ d’iris jaunes à Giverny, 1887

oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Photo:

© Bridgeman Giraudon/Press