Muscarelle Museum of Art

March 6, 2025 - May 28, 2025

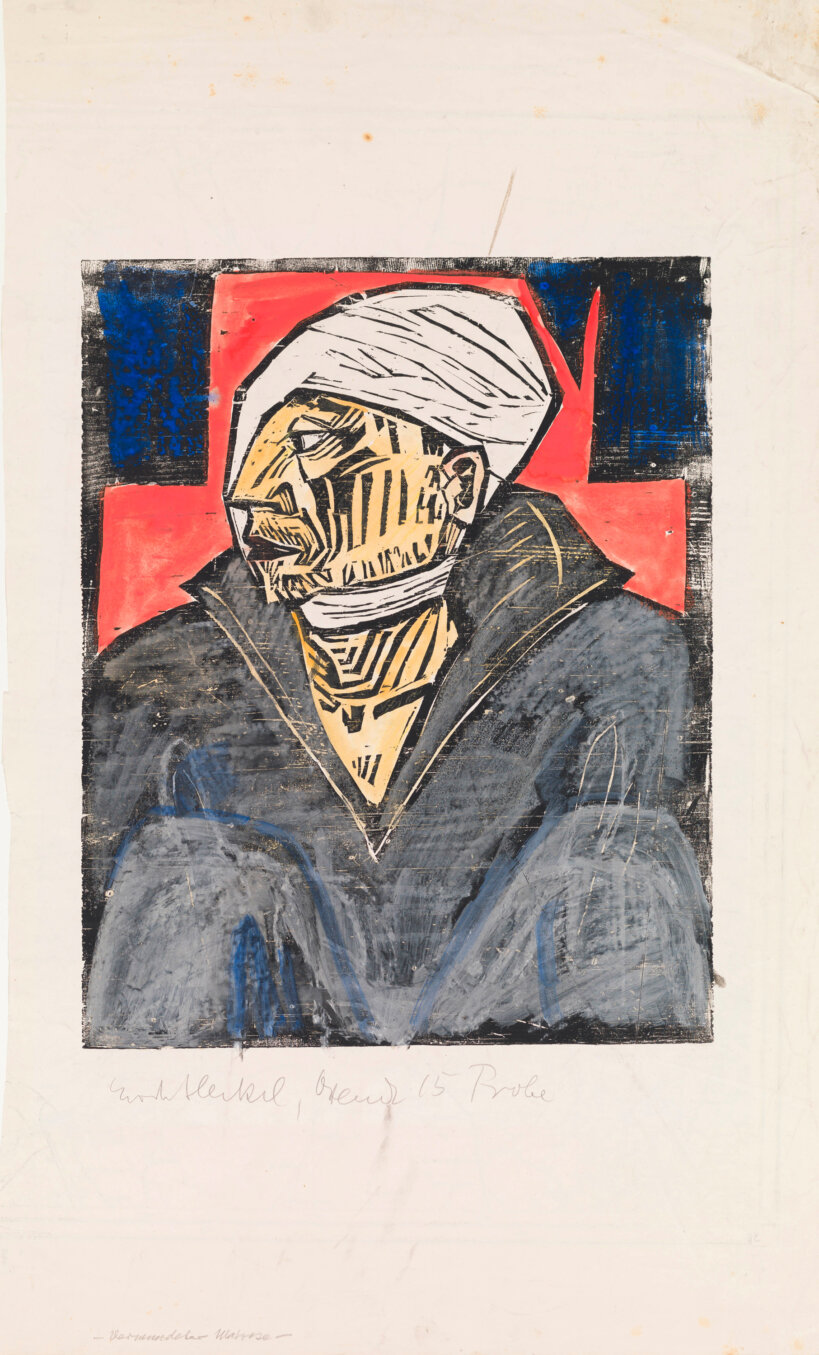

Bringing 24 rarely-displayed masterpiece drawings by Michelangelo to the United States, Michelangelo: The Genesis of the Sistine will offer American viewers an unprecedented opportunity to experience first-hand the genius of the famed artist. Displaying Michelangelo’s initial studies and early drawings of the famous frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, the exhibition will explore the rich story of the origin of these works, arguably some of the most famous in the world.

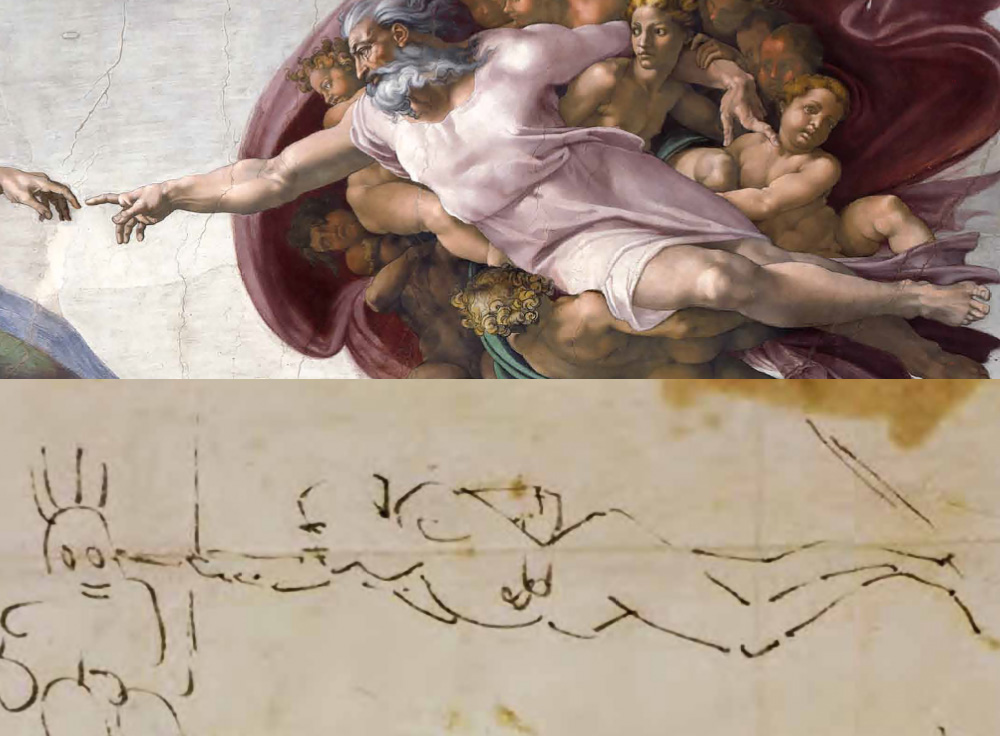

Based on 15 years of scholarship by Curator Adriano Marinazzo, the exhibition will highlight new and compelling theories about Michelangelo’s work, including a comparison between “The Creation of Adam” and a self-portrait which suggests that the artist may have envisioned himself as the Creator.

ADRIANO MARINAZZO

CURATOR OF SPECIAL PROJECTS

Adriano Marinazzo is an art and architectural historian, architect, and visual artist, recognized as a distinguished scholar of Michelangelo and Italian Renaissance art and architecture. His body of work spans exhibition catalogs, monographs, and peer-reviewed articles. Marinazzo has taught at the University of Florence and now teaches at William & Mary, focusing his research on the intersections of digital design, art, and science.

Among his key research is a groundbreaking hypothesis on a Michelangelo sketch, identified as the architectural outline for the Sistine Ceiling—possibly the first drawing made in preparation for its decoration. He presented this discovery at the XIV Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2014, later developing a multimedia work on the Sistine Ceiling’s painted architecture and publishing Michelangelo: l’Architettura. His involvement with the Muscarelle Museum began in 2008 with Painting the Italian Landscape and continued with contributions to Michelangelo: Anatomy as Architecture (2010) and Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane (2013), where he selected drawings and authored architectural catalog entries. He is currently working on special exhibitions at the Muscarelle.

Adriano Marinazzo recently connected Michelangelo's self-portrait (bottom image) to the artist's depiction of God in "The Creation of Adam” (top image).

Adriano Marinazzo, curator of special projects at the Muscarelle Museum of Art, is the inaugural designer in residence and an adjunct lecturer in the Department of Applied Science at William & Mary. He is in the first year of a three-year appointment that included teaching the new COLL 100 course Renaissance in 3D this spring and creating visual installations between art and science.

He recently made headlines across the art world for a new theory about Michelangelo and his famous work “The Creation of Adam.”

The Muscarelle sat down with the scholar for a Q&A about the discovery — and how this research ties to his work at the museum and William & Mary.

Q. You’ve curated and co-curated exhibitions on Michelangelo and written about numerous discoveries related to the artist, including his first sketch for the Sistine Chapel. How did your study of Michelangelo begin?

A. When I was six or seven, I started to be fascinated by Italian Renaissance art. I used to copy Raphael’s drawings and paintings. For my final exam in high school, I presented a detailed dissertation on Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel. It was a success! Back then, I would never have dreamt of discovering Michelangelo’s first study of the Sistine Ceiling.

Q. You recently published a new theory that compares a self-portrait sketch by Michelangelo with his depiction of God in “The Creation of Adam.” How did you make the connection between the sketch and his famous painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel?

A. I studied the original sketch in Florence at Casa Buonarroti several years ago. But, my hypothesis occurred more recently while drafting the syllabus for a new class I teach in the applied science department at William & Mary. The course, Renaissance in 3D, focuses on Renaissance art seen through the lens of digital applications. Students learn computer 3D modeling creating their original designs but also virtually recreating Leonardo’s machines/inventions, Michelangelo’s unfinished architecture and architectural projects, etc. I also wanted students to know how to present and summarize their ideas and research with just a single picture. I thought of my previous comparisons/studies on Michelangelo, and while considering additional effective comparisons, I thought of Michelangelo’s self-portrait of the Buonarroti Archive.

Q. Most Michelangelo scholars have been intrigued by your theory; what do you say to those who might be more skeptical?

A. In my study, I pointed out the intriguing resemblance between Michelangelo’s self-portrait silhouette and the artist’s depiction of God in “The Creation of Adam.” In Michelangelo’s self-portrait, his right arm is extended toward the ceiling’s surface to give life to the stories of the book of Genesis. The artist holds a brush that approaches the vault’s surface but does not touch it. This gesture recalls Michelangelo’s painting of God’s index, who gives life to Adam without touching him. Plus, in his self-portrait, Michelangelo represented himself with his legs crossed; this is a curious pose for somebody who is painting on a scaffolding. But Michelangelo also painted God with his legs crossed while giving life to Adam. I also pointed out that in his self-portrait, Michelangelo idealizes himself. The features of his face, viewed in profile, are gentle and harmonious. But in real life, Michelangelo had rough features, characterized by a flattened nose. I concluded by pointing out that Michelangelo goes towards the surface he is painting, as God goes towards Adam. The profile of the artist is flawless, like that of God.

Are all the similitudes above due to coincidence, or are they intentional? My article wants to open a conversation.

Q. Where does your research go from here?

A. I want to keep sharing my research with William & Mary students. This semester I enjoyed presenting my studies to them. They were enthusiastic. Italian masters like Brunelleschi, Leonardo and Michelangelo were both artists and scientists; they used drawing — with ink or charcoal — as scientific investigation. In my class, students learn to do the same with today’s technology.

Q. So, was Michelangelo a scientist as well as an artist?

A. Yes! In his long career, Michelangelo needed to be scientifically advanced to master the fresco technique in his paintings in the Vatican and later for his ambitious architectural and engineering designs in Rome and Florence. He also extensively studied anatomy, starting as a teenager performing corpse dissections. His scientific approach to anatomic knowledge is evident in his paintings and sketches, including his self-portrait of Casa Buonarroti. Michelangelo knew, like Leonardo, that art and science are two complementary elements of the same equation. I wish to inspire my students to be the “Leonardo” and “Michelangelo” of the future.

Q. How do you approach teaching at the intersection of art and science?

A. My students can now design in 3D; they can communicate and express themselves in a way that was impossible a few years ago. Currently, I am editing a video featuring the designs, 3D models and animations created by students this past semester to be projected in the ISC 3 lobby this summer. What we do in class is like learning a new language or musical instrument; it gives students a broader picture of our reality. It doesn’t matter what you like or study — it could be Michelangelo, biology or physics — when you learn a new communication and investigation system, you can use it as you like. This is why I envision a future visual research lab where William & Mary students and faculty experiment and exchange pioneering technologies and ideas.