Museum of Modern Art

March 31 through July 20, 2024

The Museum of Modern Art has announced the first-ever New York City museum retrospective devoted to Käthe Kollwitz, and the first major international loan exhibition of her work in the United States in more than 30 years. On view at MoMA from March 31 through July 20, 2024, Käthe Kollwitz presents a focused exploration of the artist’s career in approximately 110 rarely seen examples of her drawings, prints, and sculptures drawn from public and private collections in the US and Europe. Organized chronologically, the exhibition traces the development of Kollwitz’s work from the 1890s through the 1930s, a period of unprecedented turmoil in German history marked by the social ills of industrialization in the late 19th century and the traumas of war and political upheaval in the early 20th century. Crucial examples of the artist’s most important projects will showcase her commitment to socially critical subject matter, and key selections of preparatory studies and working proofs will highlight her creative process. Käthe Kollwitz is organized by Starr Figura, Curator, with Maggie Hire, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints.

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945) was born in the Prussian city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia). She initially trained as a painter but quickly turned to drawing and printmaking, which she saw as the most effective mediums for social criticism. She also worked occasionally in sculpture. In the early decades of the 20th century, when many artists were experimenting with the language of abstraction, Kollwitz remained committed to figuration and an art of social purpose. During an era when the leading figures in all fields were almost exclusively men, she was widely acknowledged as one of history’s most outstanding graphic artists, and became one of the few women artists to achieve international renown in her own lifetime.

As a woman confronting the injustices of her era, Kollwitz radically asserted a female point of view as a necessary and powerful agent for change. Unflinching in her pursuit of raw emotional honesty, she continually reworked her central themes of motherhood, grief, and resistance from one work to the next. Her drive was fueled by a bold ambition for herself as an artist and a dedication to bringing visibility to women and the working class. Figura explains, “Kollwitz forged an art of compassion and social conscience that resonates as powerfully today as it did in her lifetime, and this exhibition aims to reintroduce her at a moment when her commitment to social and political change is of renewed, even urgent, relevance.”

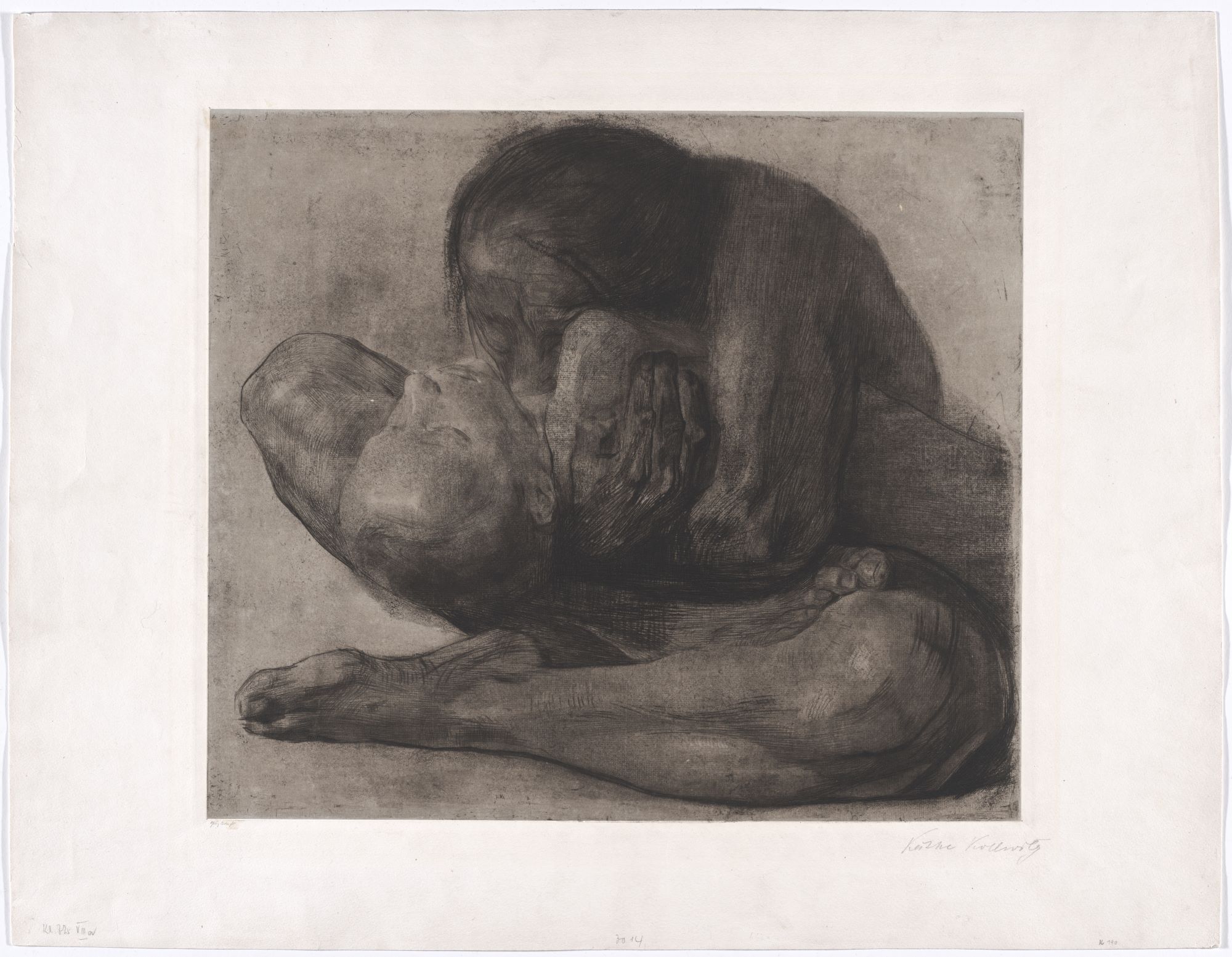

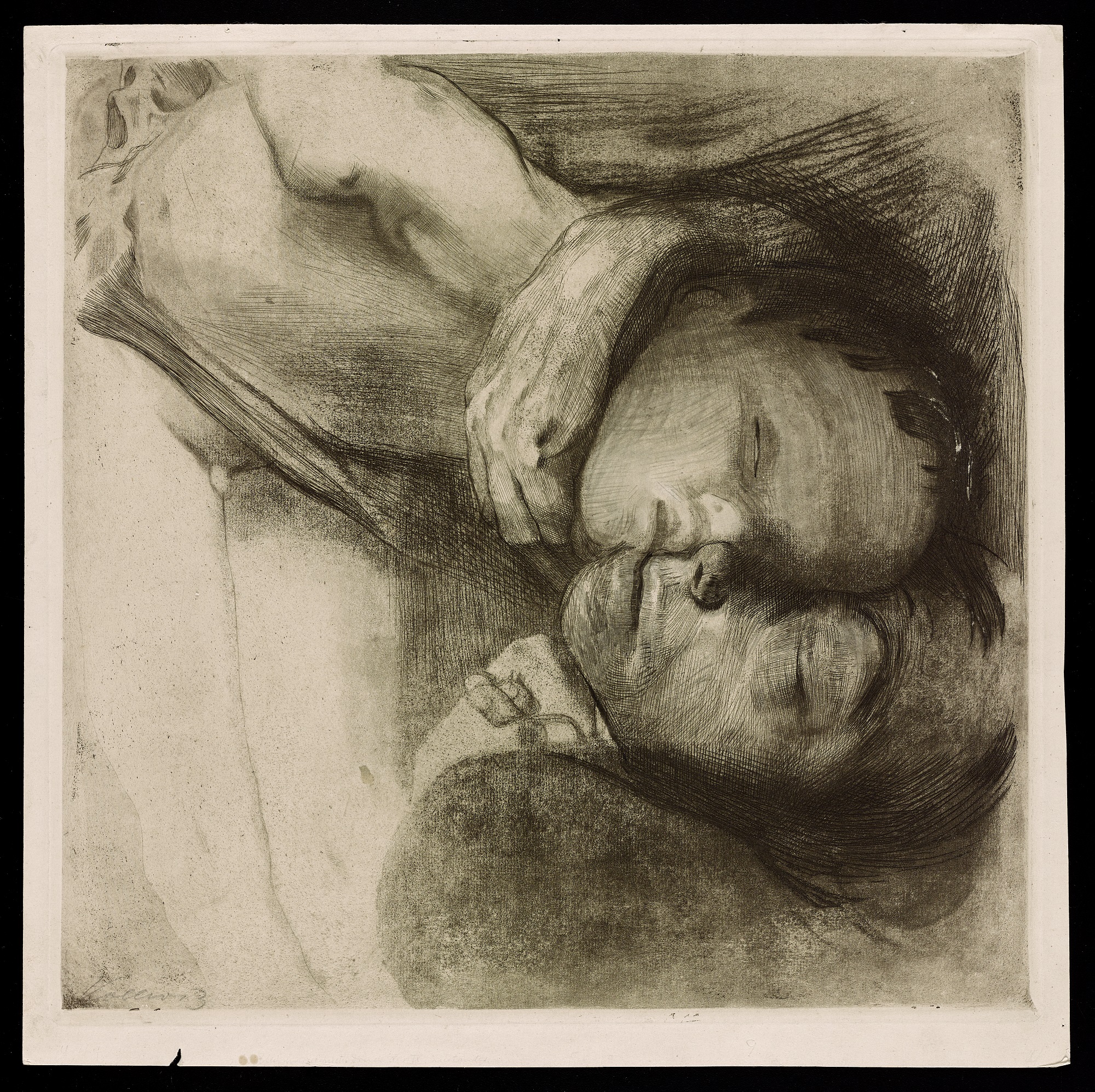

Among the pivotal works in the exhibition are Kollwitz’s iconic etching Woman with Dead Child (1903), accompanied by a revelatory sequence of studies, state proofs, and hand- colored working proofs that chart the artist’s process of conceiving and reconceiving its composition. During a period when childhood mortality was a devastating reality,

Kollwitz used the traditional Christian subject of the Pietà as a point of departure in her images of a mother grieving the loss of a child. Other highlights of the exhibition include Peasants’ War (1902-08), a print cycle that drew attention to the struggles of the working class, and War (1921-22, published 1923), a portfolio of seven woodcuts memorializing the anguish of World War I from the point of view of those left behind—parents, widows, and children.

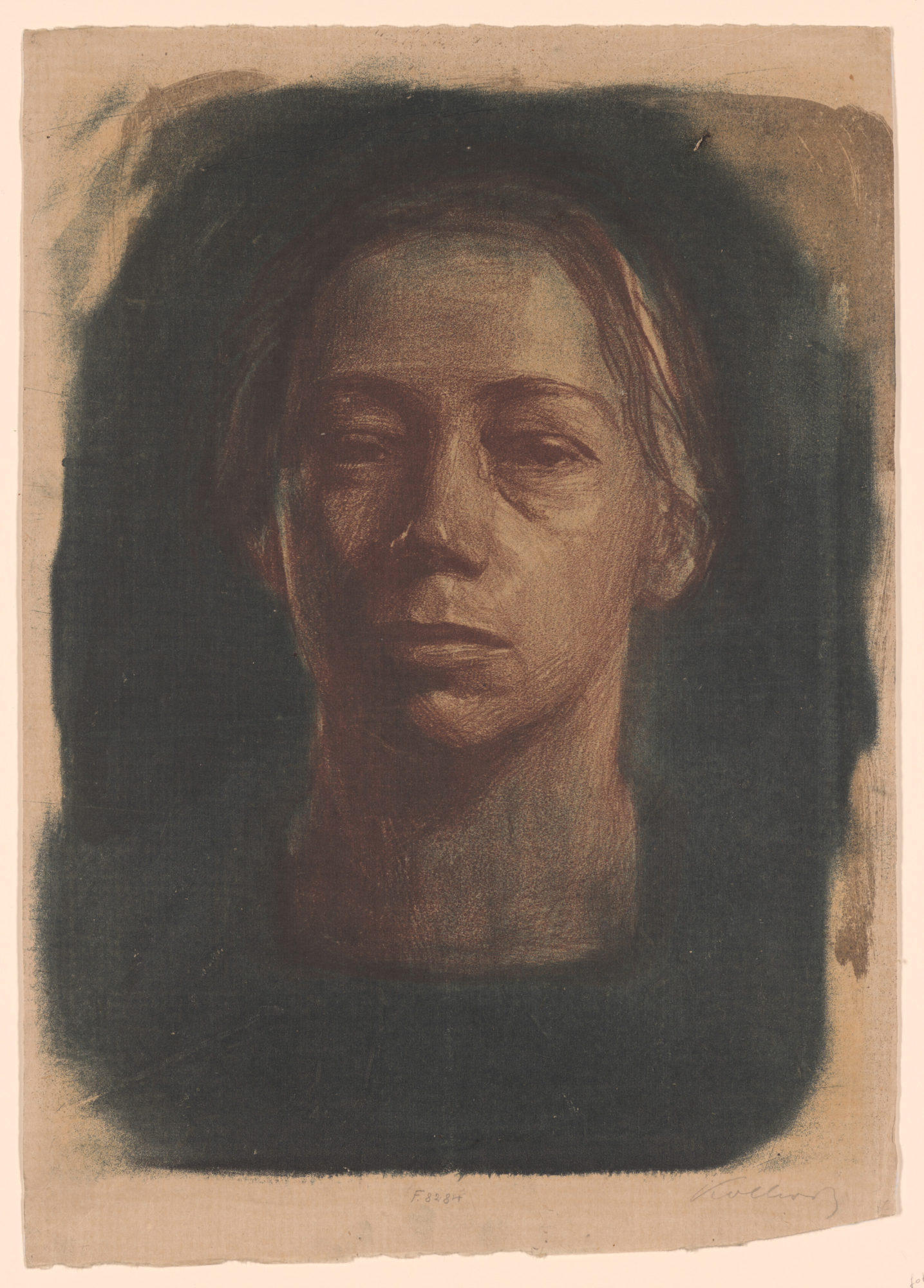

Together with the loans of many extraordinary drawings and unique prints that have rarely, if ever, been exhibited in New York, the exhibition features several important works from MoMA’s collection, including, most notably, Self-portrait en face (1904). One of the most remarkable self-portraits made in the early years of the 20th century, it was acquired jointly by The Museum of Modern Art and Neue Galerie in 2021. Käthe Kollwitz and its accompanying major publication will explore the artist’s legacy and her place in an expanded narrative of modernism.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue, edited by Starr Figura and featuring texts by Kirsty Bell, Maggie Hire, Dorothy Price, and Sarah Rapoport, that explores crucial aspects of Kollwitz's art, career, and legacy, including her professional life and connections in Berlin, her groundbreaking approach to the subject of women’s grief, and her work’s reception in the US.

SECTION TEXTS

ASSERTING HERSELF

In 1891, when Kollwitz was twenty-four years old, she married, settled in Berlin, and began her career as an artist. Within a few years, she had given birth to her two children, Hans and Peter. To be a wife and mother as well as a professional artist was virtually unheard of in her time. She was able to balance these roles thanks to her fierce sense of purpose and the support of her progressive husband, Karl, a medical doctor and socialist who believed in gender equality.

Kollwitz gained initial renown for her meticulous prints focusing on the struggles of the working class, including her first print portfolio, A Weavers’ Revolt (between 1893 and 1897). With these works, she established a lasting practice of distilling vast social problems into images ofthe painful experiences and smoldering potential of women. She would continue, throughout her life, to plumb the technical possibilities of drawing and printmaking in order to amplify that emotional content.

“My work at this time . . . was in the direction of socialism. . . . [I chose] my subjects almost exclusively from the life of the workers.”

FORGING AN ART OF SOCIAL PURPOSE

In nineteenth-century Germany, the Industrial Revolution effected a massive shift from a rural, agrarian economy to one based on industrial production in urban centers. These rapid transformations exacted a heavy toll on workers, who often suffered horrible living and labor conditions, andinflamed tensions around social inequities. In response, socialism emerged as a movement for workers’ rights and economic parity, and a push for women’s rights also gained ground. Kollwitz was committed to both of these radical causes. She focused her early work on narratives of class struggle, and, crucially, constructed many images around the actions and circumstances of women.

In Peasants’ War, her second print portfolio, Kollwitz turned to history to explore the injustices of her own time.

The project was inspired by a sixteenth-century uprising of farm laborers against the feudal landowners who exploited them. At the center of the series is “Black Anna,” a legendary leader in the conflict. Kollwitz envisions her as a powerful revolutionary whose upraised hands unleash the fury sown by centuries of oppression.

HER CREATIVE PROCESS

To develop the images in her etchings, Kollwitz often created numerous studies and draft versions that she refined or rejected along the way. She typically printed many trial proofs, testing the progress of her prints.

Occasionally she overworked these proofs with charcoal, ink, or pencil marks intended to guide the subsequent changes she would make on her metal etching plate. Together these sequential iterations map a process of refining and reconceiving in order to make her images more potent.

Exhibited here is a selection of drawings and etchings that evolved into Sharpening the Scythe (1905), a pivotal print in Kollwitz’s Peasants’ War series (on view in the adjacent gallery). The artist’s first version, at far left, shows a man guiding a downcast peasant woman in how to use a scythe.

Over the course of her revisions, which proceed clockwise around the room, Kollwitz gradually reimagined the. composition to give the woman a powerful agency. In its final form, the woman stands alone, in full command of the scythe and ready to wield it in a revolt.

“I have never done any work cold. I have always worked with my blood, so to speak. Those who see these things must feel that.”

LOVE AND GRIEF

Between 1908 and 1913 Kollwitz focused much attention on the women in the working-class neighborhood where she lived. She knew many of them as patients of her husband’s medical practice, where they sought treatment for maladies related to pollution and malnutrition, domestic violence, and unwanted pregnancy—all of which were rampant in crowded, newly industrialized cities like Berlin. “I was powerfully moved by [their] fate,” the artist wrote.

During these years, Kollwitz was also preoccupied with two emotional situations in her own life. In 1908 her sixteen-year-old son Hans contracted diphtheria, and his grave illness, coupled with the high rate of childhood mortality in her environment, affected her deeply. She made many works that depict a mother clinging to her wan son. These images of fervent embrace echo the intertwining figures in Kollwitz’s works from this period of lovers— which the artist created in the aftermath of an extramarital relationship she had. Such disparate but related visions underscore the connection between grief and love at the core of Kollwitz’s art.

“I have been through a revolution, and . . . I am no revolutionist. . . . I should hardly mount a barricade now that I know what they are like in reality.”

WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH

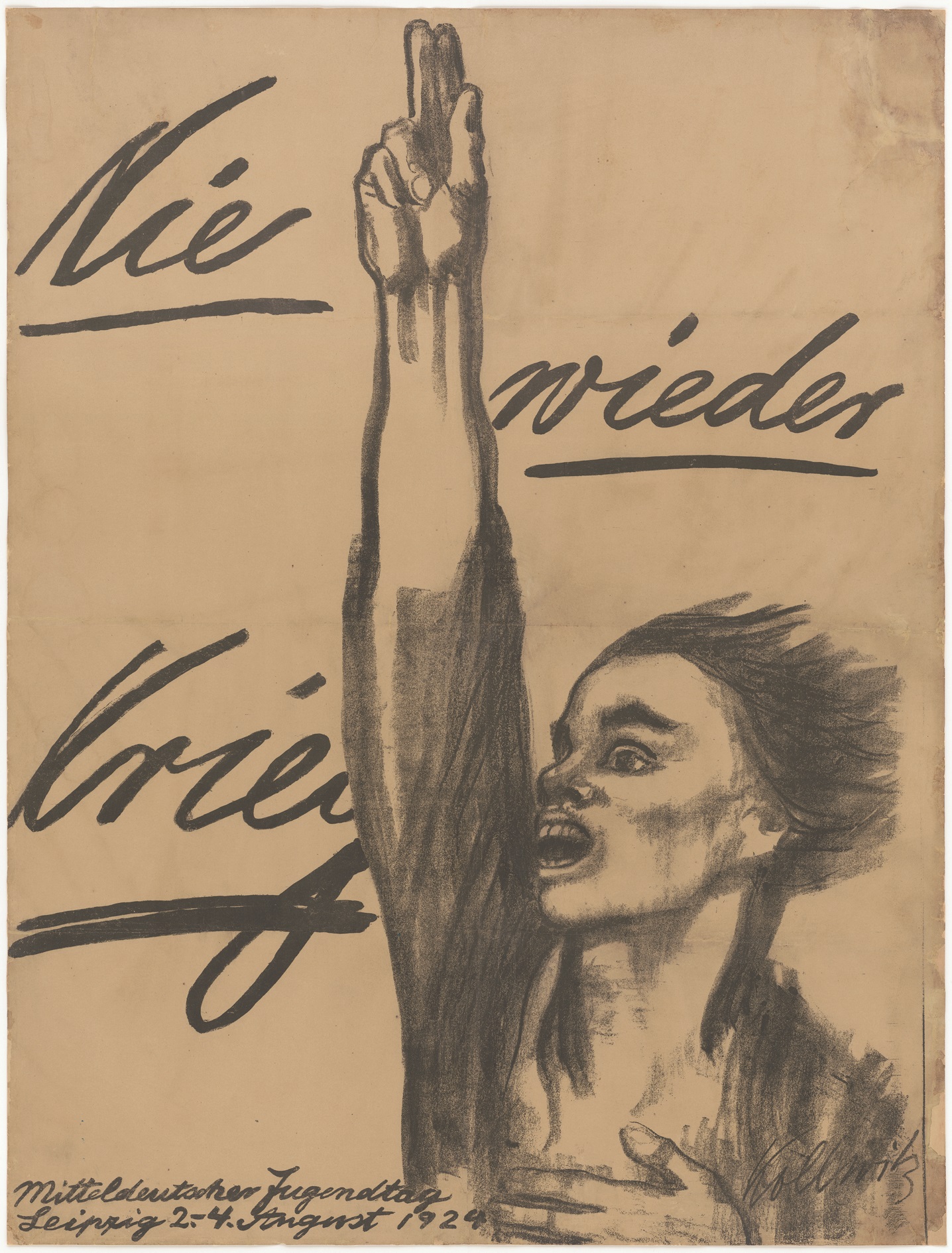

World War I (1914–18) marked a devastating turning point in Kollwitz’s life and art. In 1914, only two months after the conflict began, her eighteen-year-old son Peter was killed on the Flemish front. His death, and her role in allowing him to enlist as a minor, haunted her for the rest of her life. Her third print portfolio, War (1921–22), is a memorial to those “unspeakably difficult” years of war and her resulting turn toward pacifism. Its images of mothers safeguarding children supplanted her earlier depictions of revolutionary uprising.

In the years after the war, as a new democratic government brought more rights for women in Germany, Kollwitz rose to great prominence. In 1919 she became the first woman to be a professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts, Berlin’s leading art school. Her public presence was further elevated by the posters she produced in support of humanitarian crises wrought by the war and its turbulent aftermath. Addressing issues including famine relief, pacifism, and women’s health, they were plastered throughout the streets of Berlin and other cities.

“The most important task for someone who is aging is to spread love and warmth whenever possible.”

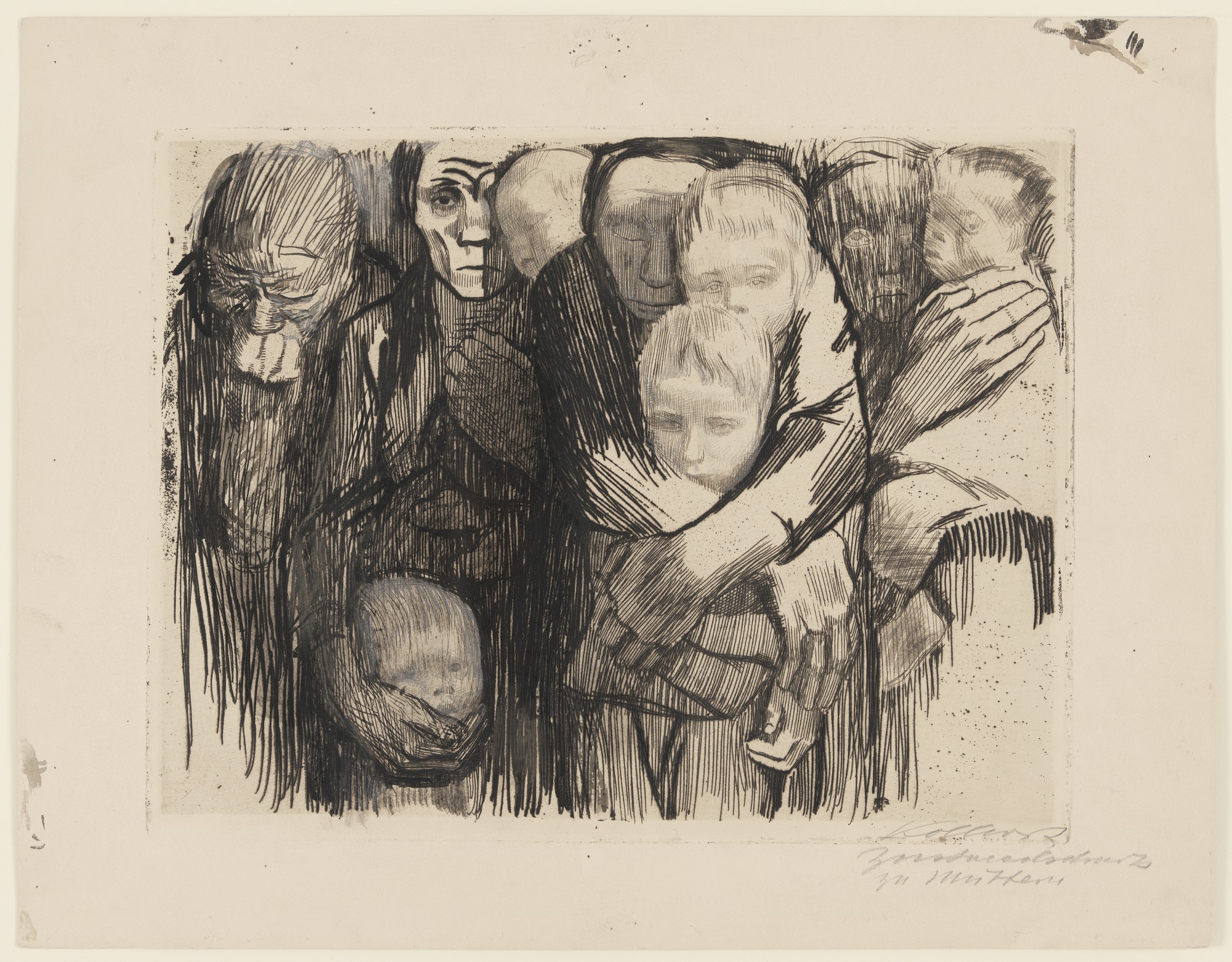

MATERNAL PROTECTION

When the Nazi party began its rise to power in the early 1930s, Kollwitz was outspoken about the danger it posed to German democracy. As a result, after Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933, she was forced to resign from her professorship at the Prussian Academy, she was prohibited from exhibiting her art, and the Gestapo threatened to send her to a concentration camp. In the midst of these intimidations, and with German fascism igniting another excruciating war in 1939, Kollwitz created many works depicting mothers with their arms encircling children. They stand as visions of maternal protection, resistance, and compassion in response to repression and terror.

In her final self-portraits, Kollwitz is frank about the toll this dark time took: she appears in them tired, with aging features. But she is unmistakably the same woman who gazed out with determination in her earliest self-images, courageously asserting herself for the cause of social justice.

Images

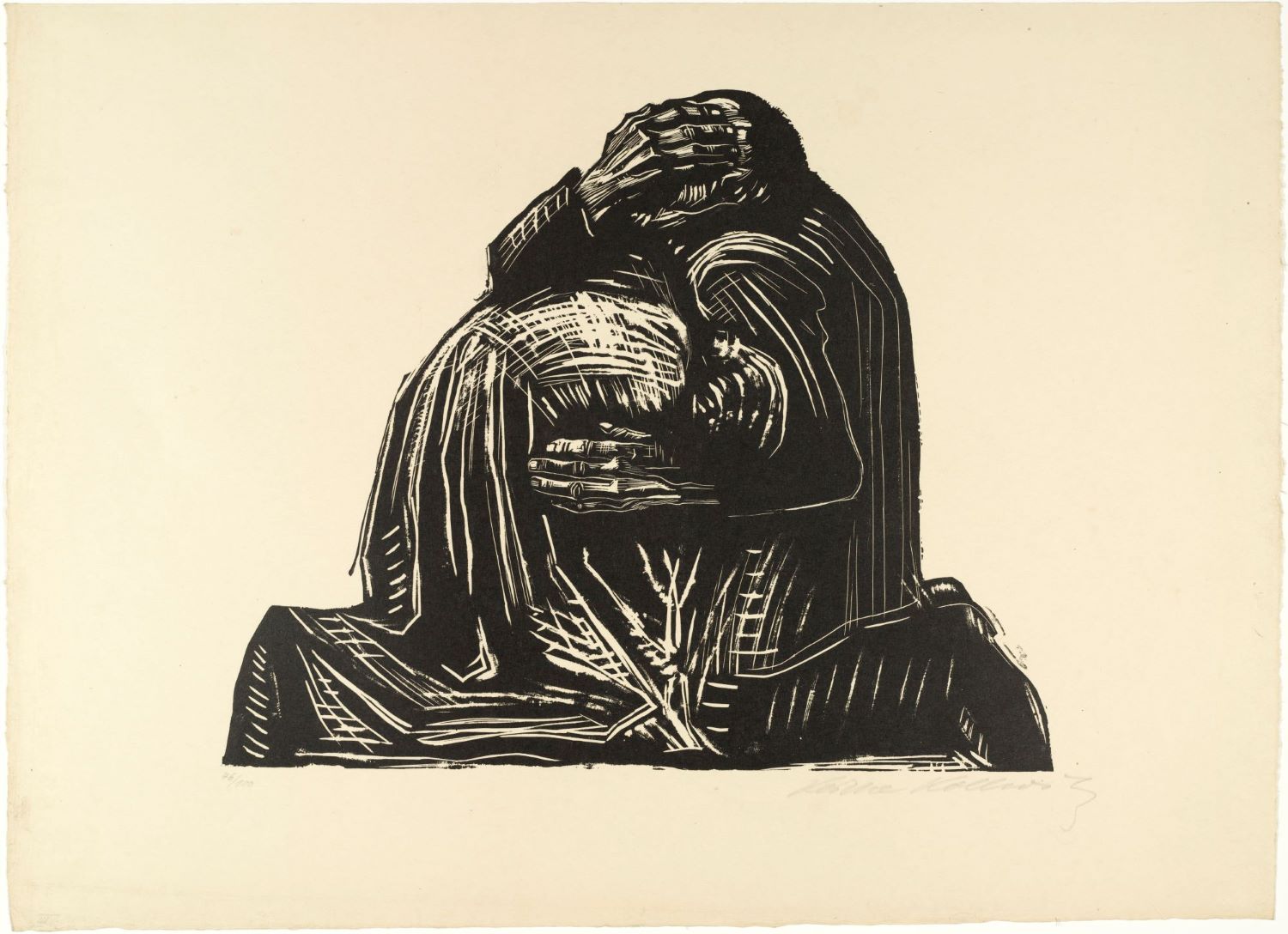

Käthe Kollwitz, The Parents (Die Eltern) from War (Krieg), 1921–22, published 1923. One from a portfolio of seven woodcuts. Composition (irreg.): 13 13/16 x 16 3/4″ (35.1 x 42.5 cm); sheet (irreg.): 18 5/8 x 25 11/16″ (47.3 x 65.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Arnhold Family in memory of Sigrid Edwards. Digital Image © 2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, photo by Robert Gerhardt

Käthe Kollwitz. Woman with Dead Child (Frau mit totem Kind). 1903. Etching with chine collé. Plate: 16 1/4 × 18 9/16″ (41.2 × 47.1 cm); sheet: 21 7/16 × 27 11/16″ (54.5 × 70.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of the Contemporary Drawing and Print Associates. Digital image © 2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, photo by Robert Gerhardt

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait en Face (Selbstbildnis en face), c.1904. Lithograph. Composition: 17 5/16 x 13 3/8″ (44 x 34 cm); sheet: 18 7/8 × 13 3/8″ (47.9 × 34 cm). Jointly owned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York (The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Endowment for Prints, and gift of Jack Shear, Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin, Alice and Tom Tisch [in honor of Marlene Hess], Kathy and Richard S. Fuld, Jr., Emily Rauh Pulitzer, Maud I. Welles, Ronnie Heyman [in honor of Marlene Hess], and Carol and Morton Rapp) and Neue Galerie New York (Gift of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder). Digital Image © 2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, photo by Robert Gerhardt

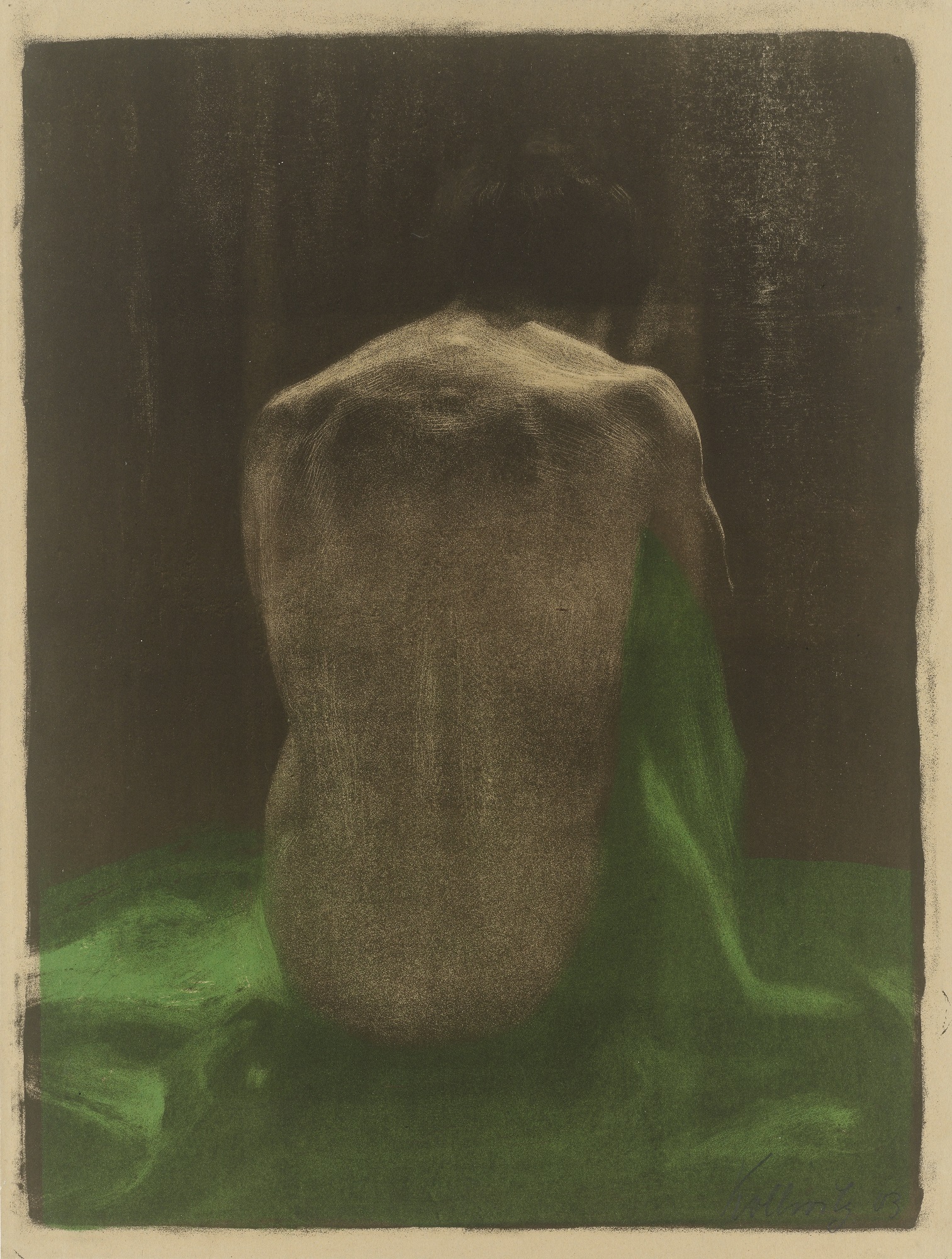

Käthe Kollwitz. Female Nude, from Behind, on Green Cloth (Weiblicher Rückenakt auf grünem Tuch). 1903. Crayon and brush lithograph with scraping needle, printed in two colors on brown paper. Composition: 22 13/16 x 17 15/16″ (58 x 44 cm); sheet: 24 x 18 ¼” (61 x 46.3 cm). Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, photo: Herbert Boswank

Käthe Kollwitz. Woman with Dead Child (Frau mit totem Kind). 1903. Line etching, drypoint, and sandpaper, with imprint of laid paper and Ziegler’s transfer paper, overworked with charcoal and blue wash, heightened with white. Sheet (trimmed to and within plate mark): 16 5/16 × 18 5/8″ (41.5 × 47.3 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Gift of Molly and Walter Bareiss. Image © Yale University Art Gallery

Käthe Kollwitz. The Mothers (Mütter). 1918. Line etching, sandpaper, needle bundle, and soft ground with the imprint of laid paper overworked with black ink, opaque white, charcoal, and pencil. Plate: 9 5/8 x 12 1/2″ (24.5 x 31.8 cm); sheet 12 5/8 x 16 5/16″ (32 x 41.4 cm). Collection Ute Kahl, Cologne. Fuis Photographie

Käthe Kollwitz. Never Again War! (Nie wieder Krieg!). 1924. Crayon and brush lithograph. Composition: 37 x 30″ (94 x 68.5 cm); sheet 37 3/16 x 28 ¼” (94.5 x 71.8 cm). Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum Berlin/Association of Friends of Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum Berlin. © Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum Berlin/Association of Friends of the Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum Berlin

Käthe Kollwitz. Death Woman and Child (Tod, Frau und Kind). 1910. Line etching, drypoint, sandpaper, and soft ground with the imprint of laid paper and Ziegler’s transfer paper, overworked in pencil and black ink. Plate: 15 7/8 x 16″ (40.4 X 40.7 cm); sheet: 16 15/16 x 16 15/16″ (43 x 43 cm). Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Partial gift of Dr. Richard A. Simms. Image courtesy Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Käthe Kollwitz. Mother, Clutching Two Children (Mutter, zwei Kinder an sich pressend). 1932. Charcoal on paper. 25 3/8 x 19″ (64.4 x 48.3 cm). Käthe Kollwitz Cologne. Image courtesy Käthe Kollwitz Museum Cologne