The Louvre

16 OCTOBRE 2024 —3 FEBRUARY 2025

‘The Louvre’s enigmatic painting par excellence.’

These are the words that the painter and writer Bernard Dufour

used to describe Pierrot, long known as Gilles, by Antoine

Watteau (1684–1721). Though this strange character, dressed in

white from top to toe, cuts a familiar, even iconic gure, this is a

work of absolute originality. From its history to its composition,

from its format to its iconography, everything about this piece

captivates and intrigues.

Its origins remain unknown; the rst conrmed mention of its

existence only dates back to 1826. Interpreting this painting,

inspired by the world of theatre and particularly by Pierrot, the

most famous comedy character of this period, is also a difcult

task.

Thanks to recent conservation work carried out at the Centre

for Research and Restoration of Museums of France (C2RMF),

which has restored the painting to its former glory, the Musée

du Louvre is nally able to give it the monographic exhibition it

so richly deserves. The exhibition will explore this mysterious

masterpiece, placing it back into the context of theatre life at the

start of the 18th century and of the artworks produced by

Watteau and his contemporaries. It will also touch on the

fascination that Gilles has inspired all the way to the present

day, inuencing creators of all backgrounds from Fragonard to

Picasso to Nadar, from André Derain to Marcel Carné. Each of

these painters, authors, actors, photographers and lmmakers

made a talented attempt at solving its captivating riddle.

The exhibition presents sixty-five works (paintings, drawings, engravings, books, photographs and film excerpts), including seven paintings by Watteau, thanks to the support of various French, European and American museums, including the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the Wallace Collection and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Standing as an eternally blank page in spite of countless interpretations, Pierrot is still an actor with no lines... and a painting with no equal.

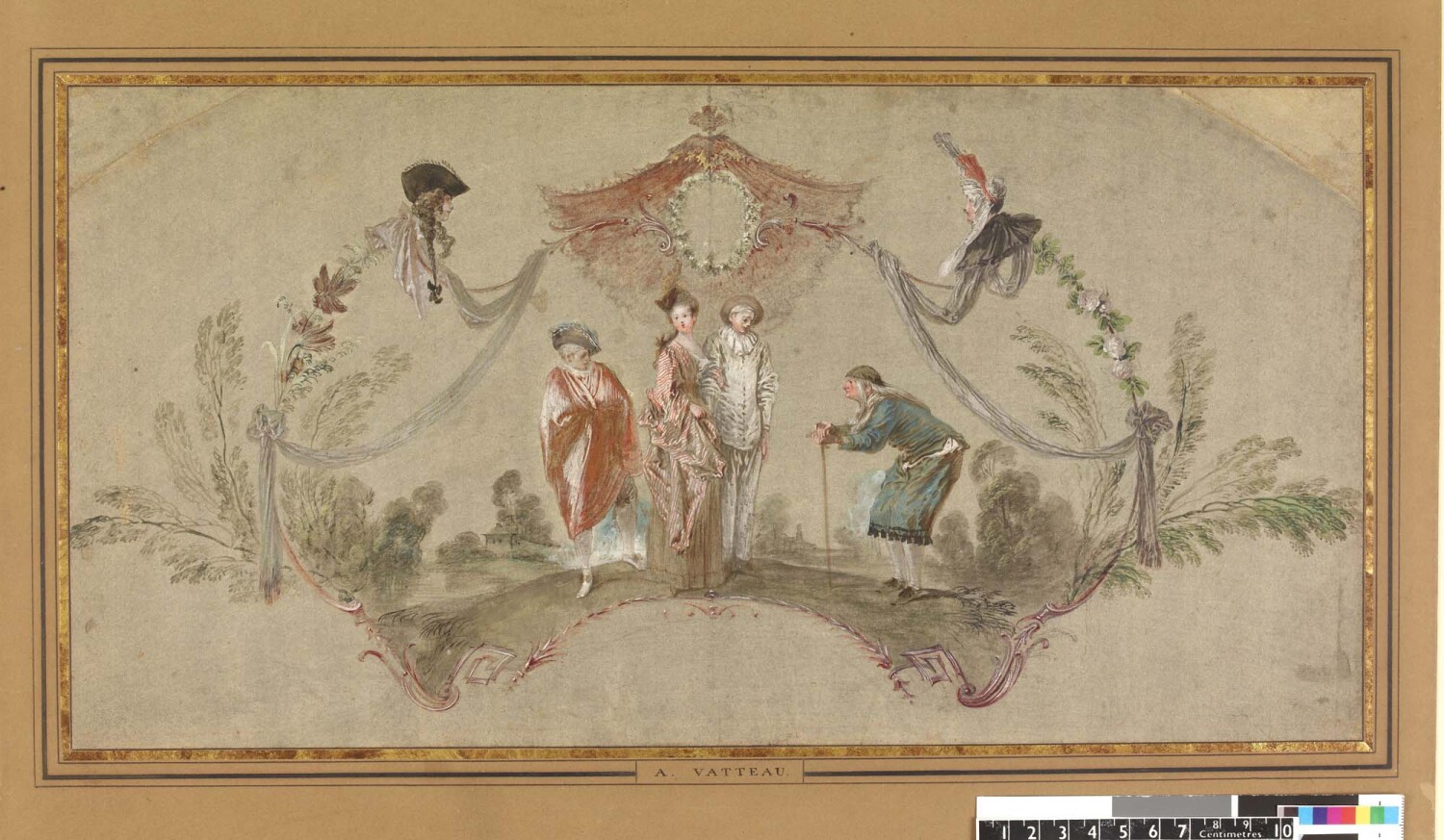

Pierrot and Comedy in Watteau’s Time

In the beginning of the 18th century, the Parisian comedy world was the scene of a erce rivalry between different acting troupes. The two ofcial companies each upheld their star performers: Crispin, the scheming valet, made top billing at the Comédie-Française, while Harlequin and Pierrot, the jesting servant pair, thrilled the public at the Comédie-Italienne. However, the latter company was forbidden to play between 1697 and 1716. Meanwhile, private troupes, whose burlesque – and occasionally, mimed – repertoire was exhibited at Parisian fairs, won public acclaim when they borrowed the characters of Harlequin and Pierrot, but their representations were often halted, or even banned, by the ofcial playing companies. At the so-called ‘Théâtre de la Foire’, or theatre played at seasonal fairs, acting troupes put on public performances on outdoor trestle stages to bring in audiences. Many engravings publicised these very popular shows.

Watteau and the Theatre

Hailing from Valenciennes (northern France), the painter Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) moved to Paris around 1702. His apparently early interest for the world of theatre was amplified by his collaboration with Claude Gillot, who specialised in depictions of Comédie-Italienne scenes, around 1705–1709. Watteau’s personal work later gave pride of place to the repertoire of comedy. In several self-portraits, he seemed to depict himself with features that were most common in comic theatre, a most peculiar choice at a time when actors lingered at the lower rungs of the social ladder.

2 -

Watteau and the Creation of Pierrot

The Louvre’s Pierrot is quite a mysterious painting. The circumstances of its creation are unknown and its subject is difcult to interpret. It has been suggested, without concrete proof, that this work may have served as the sign for a café run by a former actor who specialised in the Pierrot role, or as an advertisement for a play shown at a fair. Its very attribution to Watteau has sometimes been contested; this painting’s large format does indeed set it apart from the rest of the great master’s oeuvre. And yet, Pierrot’s frontal, symmetrical presentation and his ramrod-straight posture are probably of Watteau’s invention. The composition includes some unique elements which appear in other works by the same master, such as the faun-headed sculpture and the surprising association of Pierrot with the character of Crispin. Both the style and the incredible quality of the work support its attribution to Watteau.

3 -

Watteau’s Pierrots and Posterity in the 18th Century

After 1720, the character of Pierrot lost some wind on the Parisian theatre scene. However, a new comedy character conquered the fairground trestle stage, and would remain there until the end of the century: Gilles. Sporting an identical white costume, he was derived from the Pierrot character, yet altered: a crass, lascivious valet, fomenting schemes that were generally to the detriment of his master Cassandre.

Though the painting that the Louvre holds today seems to have remained in obscurity in the 18th century, French painters continued to nd inspiration in the character of Pierrot as he had been recorded by Watteau. The rst of these were the artists who were close with the Valenciennes master: Jean-Baptiste Pater and Nicolas Lancret. In the 1780s, Fragonard painted a charming portrait of a child in a Pierrot costume, in which we can feel the spirit of Watteau.

4 -

Discovering Gilles

The rst conrmed mention of the Pierrot held by the Louvre dates back to 1826. The painting was then part of the private collection of Dominique-Vivant Denon (1747–1825), former Director of the Louvre. The work was immediately identied as a Watteau masterpiece and was given the name Gilles in reference to the stock character that was so in vogue in the second half of the 18th century.

From then on, this work, frequently shown in exhibitions, progressively rose to great fame, until it joined the Musée du Louvre’s collection in 1869, through a bequest by Doctor Louis La Caze (1796– 1869). At the end of the 19th century, its considerable renown inspired novels and musical representations.

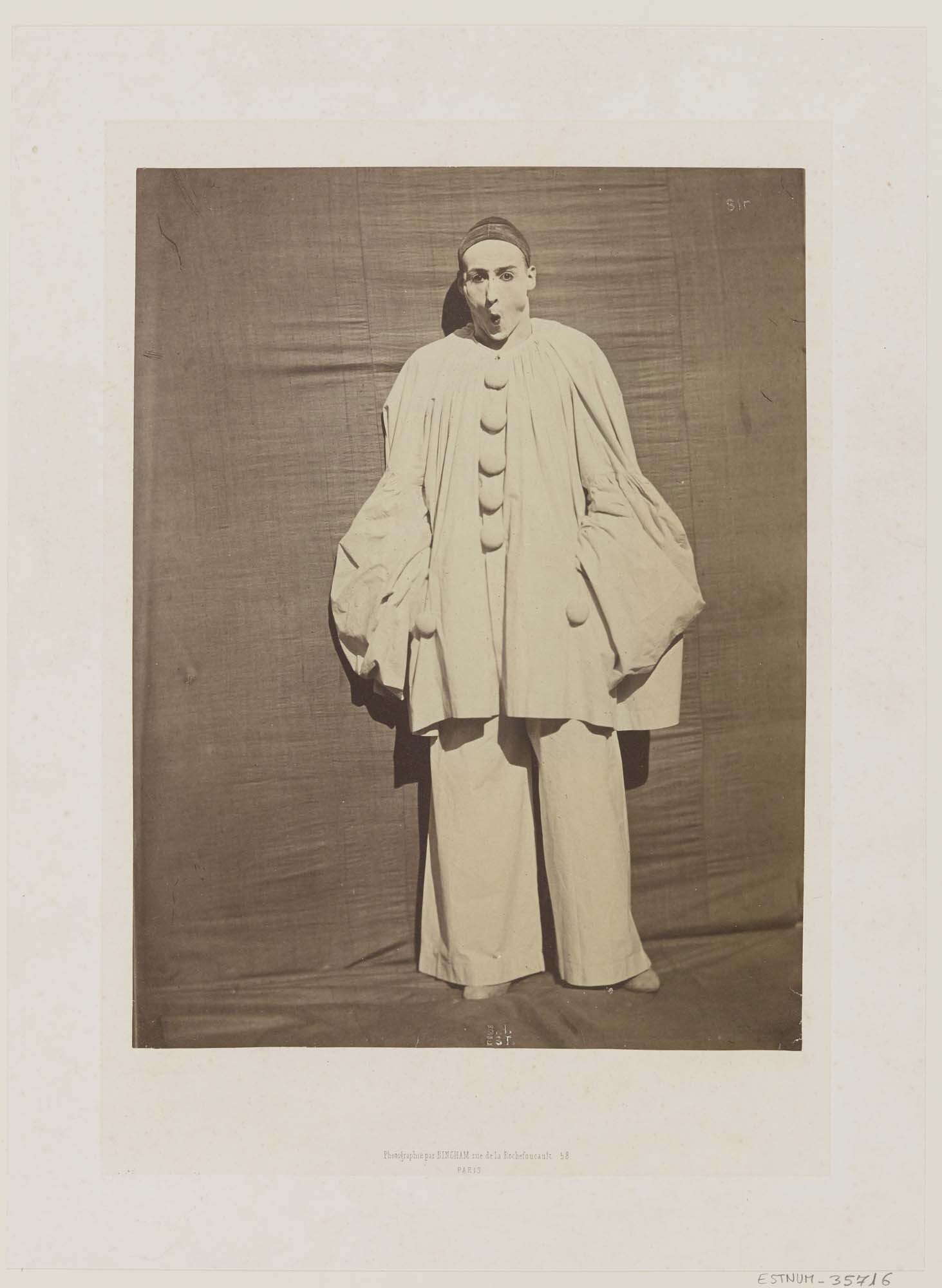

The Evolution of the Pierrot Character in the 19th Century

Beginning in the 1820s, the character of Pierrot was profoundly transformed by a brillant actor called Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846). Dedicated to pantomime, a genre of theatre based on mime, he modified both the character’s costume and his temperament. His silhouette became thinner, drowning in a too-big white costume, and took on an androgynous aspect. His personality, dreamier and more serious, even in the most comical situations, occasionally took an eerie turn, and could even adopt the tropes of drama and tragedy.

The character evolved in parallel with the public’s gradual rediscovery of Watteau’s Gilles; the two influenced each other. The various interpretations of the painting were coloured by the writings and shows featuring Pierrot. In turn, the iconography of the character – whether painted, engraved or photographed – was informed by the Louvre’s masterpiece.

5 -

Pierrot’s Modernity

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the character of Pierrot and the painting by Watteau, frequently

highlighted in the Louvre galleries, remained a wellspring of inspiration for artists.

The worlds of theatre and lm, with shows by the mime Marcel Marceau or the lm Children of

Paradise, continued to reinterpret the character in a dramatic and poetic vein. Painters also took up the

challenge of depicting the ‘great white shape standing starkly against the blue sky’ that characterised

Watteau’s painting. Picasso, André Derain, Juan Gris, Georges Rouault and Jean-Michel Alberola each

took on this enigmatic gure to give it their own twist, offering tragic visions, playful deconstructions

and enigmatic absences.

EXHIBITION CURATOR: Guillaume Faroult, Executive Curator of the Department of Paintings, Musée du Louvre.

CATALOGUE: by Guillaume Faroult, co-published by Musée du Louvre Éditions and Liénart Éditions, 240 pages, 150 illustrations, €40.

Images

1. Watteau, Pierrot, dit le Gilles_APRES restauration © RMN - Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)_Mathieu Rabeau-

2. Karel Dujardin, Les Charlatans italiens © GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre),Tony Querrec-

3. Bernard Picart, Evariste Gherardi dit Arlequin dans un personnage de la Comédie Italienne © 2009 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn, Suzanne Nagy

4. Antoine Watteau, Arlequin empereur de la lune © Musée d'arts de Nantes_photographie, Cécile Clos

5. Louis Crépy d'après Antoine Watteau, Autoportrait d’Antoine Watteau © Bibliothèque nationale de Franc

6. Antoine Watteau, La Coquette, Londres © The Trustees of the British Museum

7. Antoine Watteau, Pierrot content, Madrid © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisz

8. Antoine Watteau, L’Amour au théâtre italien © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie Jörg P. Anders. Marque du Domaine Public 1.0 universel

9. Antoine Watteau, La Partie quarrée © Photo Joseph McDonald. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco-

10. Watteau, Pierrot, Haarlem © Teylers Museum-

11. Antoine Watteau, Les comédiens italiens, Washington. CCO Courtesy National Gallery of Art-

12. Nicolas Lancret, Les Acteurs de la Comédie Italienne © GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) Stéphane Maréchalle

13. Jean Honoré Fragonard, L'Enfant en Pierrot © Wallace Collection, London, UK Bridgeman Images-

14. Adrien Tournachon, Pierrot surpris © Bibliothèque nationale de France

15. Paul Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt dans Pierrot assassin pantomime de Jean Richepin © Bibliothèque nationale de France

16. Cecil Beaton, Greta Garbo en Pierrot © National Portrait Gallery, Vogue, Condé Nast

17. Pablo Picasso, Paul en Pierrot, 1925 © Succession Picasso 2024 photo © GrandPalaisRmn (musée national Picasso-Paris), Mathieu Rabeau-

18. André Derain, Arlequin et Pierrot, vers 1924 © Adagp, Paris, 2024 photo © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de l'Orangerie), Hervé Lewandowski

20. Jean-Michel Alberola, Le projectionniste, 1992 © Adagp, Paris, 2024 photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. GrandPalaisRmn Georges Meguerditchian