On 3 July, Sotheby’s will bring to auction

a newly-discovered

painting of Olimpia Pamphilj by Spanish master, Diego Velázquez. Lost for

almost three centuries, this captivating portrait once formed part of the

illustrious collection of Don Gaspar Mendez de Haro y Guzman, 7th Marques del

Carpio - one of the greatest patrons

and collectors of arts in 17th-century Italy. Last recorded in 1724, it subsequently

disappeared without trace. The

whereabouts of the painting remained completely unknown

until one day, an

unattributed work, sold in the 1980s as

‘anonymous Dutch school’, was brought into Sotheby’s Amsterdam office. An

intriguing old cypher hidden on the back of the painting

prompted Sotheby’s specialists to begin a

process of research and

discovery – all of which ultimately lead to the realisation that this striking portrait

was the long-lost original by Velázquez:

a painting much revered in

its day and executed during the artist’s ‘golden period’.

James Macdonald, Sotheby’s Senior Specialist of Old Master Paintings, said: ‘The search for Velázquez’s portrait of Donna Olimpia is finally over. Painted in Rome in 1650 by perhaps the greatest portrait painter of all time, this depiction of one of the most powerful and domineering woman of her time has long been recorded through early documents and engravings but was lost for nearly 300 years. Its recent rediscovery represents a highly significant addition to the great Spanish master’s oeuvre and the painting can be counted amongst only a handful of works by the artist remaining in private hands today.’

Painted in 1649-50 during Velázquez’s second trip to Rome, the Portrait of Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj (est. £2 - 3 million) will be offered at Sotheby’s London on July 3rd in the context of one of the strongest Old Master sales ever staged. On view to the public from 28th June till 3rd July, it will hang alongside major works by the titans of British Art – Thomas Gainsborough, John Constable, J.M.W. Turner – as well as leading Renaissance and Baroque painters Botticelli, Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Sir Peter Paul Rubens. A newly discovered drawing by 16th century Mannerist artist Rosso Fiorentino will also be unveiled to the public for the first time. The portrait of Olimpia belongs to a moment during which Velázquez produced some of his most celebrated masterpieces, including the Portrait of Pope Innocent X – a work that was to have a profound influence on subsequent generations of artists, culminating most famously in Francis Bacon’s seminal Pope series. One of a few, and the only lady, to be selected to be painted by Velázquez during his visit, the painting depicts a stout, strong-jowled woman, and exudes the artist’s unique ability to capture and convey the personalities of his sitters.

Commissioned either by, or for Olimpia herself, the painting is documented as having been in the collections of numerous notable figures of 17th and 18th century Rome, including the sitter’s grandson Cardinal Camillo Massimi, a famous connoisseur and art patron, and Don Gaspar Mendez de Haro y Guzman, 7th Marques del Carpio, who by his death had amassed over 1,800 paintings for his collection, including no fewer than six paintings by Velázquez. Well documented in a number of collections thereafter, the painting was last recorded as being in the collection of Cardinal Pompeo Aldrovandi of Bologna and Rome in 1724, after which traces of the work are lost.

Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj

Born into a noble family in Viterbo in 1591, Olimpia married and was widowed twice, latterly by Pamphilio Pamphilj, the elder brother of Cardinal Giambattista Pamphilj, later elected Pope Innocent X in 1644. The Pope’s sister-in-law and his reputed lover, Olimpia Pamphilj was one of the most influential figures at the papal court during her brother-in-law’s tenure. Her influence over the pontiff was well-known with one Cardinal, Alessandro Bichi, on the election of Innocent in October 1644, supposedly angrily declaring, “Gentlemen, we have just elected a female pope.”

Eleanor Herman, New York Times best-selling author and writer of a captivating biography of Olimpia Pamphilj, ‘Mistress of the Vatican’ comments: ‘The most powerful and notorious woman of her time, Olimpia Maidalchini was a baroque rock star. Women from all over the Catholic world came to Rome to station themselves outside her palace to cheer as her carriage rolled out. They could not believe that a female from modest beginnings had risen to such heights – running the nation of the Papal States and the Catholic Church, an institution where women were not allowed any power.’ Nicknamed ‘Papessa’ – the ‘lady Pope’, Olimpia effectively controlled appointments at Papal Court with candidates for vacant episcopal roles applying directly to her, and the office typically going to the highest bidder.

In 1645 she received the title Princess of San Martino, a position she used in court to bring considerable wealth to the house of Pamphilj. Her influence subsided somewhat following the recalling by Innocent X of Fabio Chigi from Germany, who subsequently became Pope Alexander VII, however, in the last years of Innocent’s life, she guarded access to him and used her position for her own financial gain.

Having constantly feared being condemned to a convent as a young woman – the fate of many a dowerless young lady of the time – Olimpia was empathetic to the plight of her own sex. Contemporary accounts describe how she gave money to women to save them from this fate, delivering provisions to convents and building hundreds of homes as dowries for girls who would otherwise not be able to marry and would be forced into a convent or prostitution. She was also said to have allowed prostitutes in Rome to ride in carriages bearing her coat of arms to indicate that they were under her protection.

Olimpia was also a patron of Roman culture sponsoring numerous artists, musicians, playwrights and sculptors and was responsible for Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in the Piazza Navona in Rome designed and created for Pope Innocent X in 1651.

The Discovery

ThePortrait of Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj was last documented alongside Velázquez’s celebrated portrait of her grandson, Cardinal Camillo Massimi, in the collection of Cardinal Pompeo Aldrovandi (1668 – 1752) of Bologna and Rome, in 1724. While the subsequent ownership of Camillo’s portrait is well-documented through to its current location in Kingston Lacy, Dorset, records of the portrait of Olimpia end with Aldrovandi.

The only clue to its whereabouts for almost 300 years before it re-appearance at a Dutch auction house in 1986, is an old custom stamp on the reverse of the former stretcher, indicating that the painting had left Italy in 1911. Brought to the attention of Sotheby’s specialists in Amsterdam who immediately recognised the mysterious cypher on the back of the painting as that of Don Gaspar Mendez de Haro y Guzman, 7th Marques del Carpio, the process of establishing the true creator of the work began in earnest.

Viewing the painting and tracking down various inventories from the 17th and 18th centuries, Sotheby’s Senior Specialist, James Macdonald, soon suspected that this striking portrait could be the hitherto missing original by Velázquez. Showing the painting to key experts in the field, the attribution of the work was confirmed, making the portrait one of only a handful of paintings by the great Spanish artist left in private hands.

Another great discovery: a rare, long-lost drawing by Rosso Fiorentino.

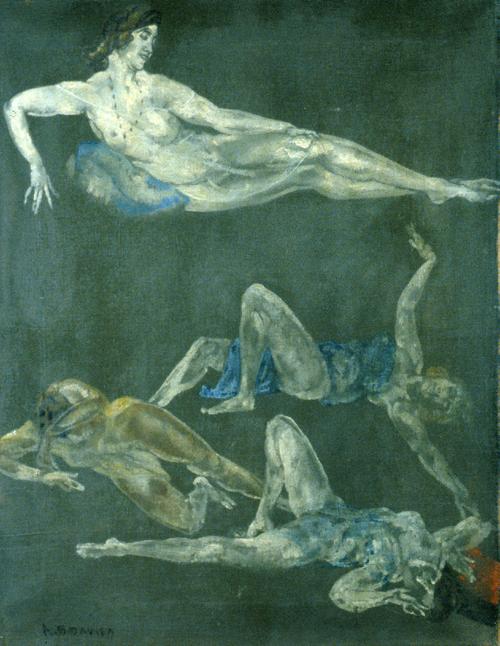

Scrolling through a batch of images sent through from around the world via Sotheby's online valuation tool Cristiana Romalli, Senior Director and Italian specialist in Sotheby’s Old Master Drawings Department, paused at an intriguingly accomplished sketch. It looked to her like an accomplished work by major Mannerist artist, Rosso Fiorentino, whose drawings are extremely rare.

Cristiana retired home to read Giorgio Vasari’s ‘Lives of the Artists’, chronicling the lives of the leading Italian artists of the early 16th-century. And there she found a reference to this work, since then unrecorded – lost from the canon of art history.

Vasari describes how, in 1524, Rosso set out from Florence to Rome, in search of work. He stopped en route in his home town of Arezzo, where he caught up with his old friend Antonio Lappoli (1492-1552). Lappoli – a less successful artist than Rosso – had just been asked to complete a major commission in Arrezzo: a rendering of the Visitation, for the family chapel of a wealthy Aretine citizen. Lappoli turned to his friend Rosso for help and inspiration, and Rosso, forever generous, worked up this beautifully accomplished composition, which Lappoli then used as the basis for his painting.

The beautiful drawing by Rosso – described by Vasari asmolto bello – was believed by scholars to be lost. Its re-emergence now adds significantly to our understanding of the working methods of an artist known for his eccentricity, and expressive, unconventional style. Only the second drawing by Rosso to have appeared on the market in over half a century, its survival and fine state of preservation is nothing short of miraculous.

That it has clearly been handled with care over the last 500 years is perhaps largely thanks to an old attribution to Michelangelo, penned on the back of the drawing in a 17th-century hand; partly too because it has enjoyed the lucky fate of having, since the 18th century, just one careful family of owners. Watch Cristiana Romalli talk about the process of discovery here. The drawing will be offered as a highlight of Sotheby’s Old Master and British Works on Paper sale on 3 July.

James Macdonald, Sotheby’s Senior Specialist of Old Master Paintings, said: ‘The search for Velázquez’s portrait of Donna Olimpia is finally over. Painted in Rome in 1650 by perhaps the greatest portrait painter of all time, this depiction of one of the most powerful and domineering woman of her time has long been recorded through early documents and engravings but was lost for nearly 300 years. Its recent rediscovery represents a highly significant addition to the great Spanish master’s oeuvre and the painting can be counted amongst only a handful of works by the artist remaining in private hands today.’

Painted in 1649-50 during Velázquez’s second trip to Rome, the Portrait of Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj (est. £2 - 3 million) will be offered at Sotheby’s London on July 3rd in the context of one of the strongest Old Master sales ever staged. On view to the public from 28th June till 3rd July, it will hang alongside major works by the titans of British Art – Thomas Gainsborough, John Constable, J.M.W. Turner – as well as leading Renaissance and Baroque painters Botticelli, Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Sir Peter Paul Rubens. A newly discovered drawing by 16th century Mannerist artist Rosso Fiorentino will also be unveiled to the public for the first time. The portrait of Olimpia belongs to a moment during which Velázquez produced some of his most celebrated masterpieces, including the Portrait of Pope Innocent X – a work that was to have a profound influence on subsequent generations of artists, culminating most famously in Francis Bacon’s seminal Pope series. One of a few, and the only lady, to be selected to be painted by Velázquez during his visit, the painting depicts a stout, strong-jowled woman, and exudes the artist’s unique ability to capture and convey the personalities of his sitters.

Commissioned either by, or for Olimpia herself, the painting is documented as having been in the collections of numerous notable figures of 17th and 18th century Rome, including the sitter’s grandson Cardinal Camillo Massimi, a famous connoisseur and art patron, and Don Gaspar Mendez de Haro y Guzman, 7th Marques del Carpio, who by his death had amassed over 1,800 paintings for his collection, including no fewer than six paintings by Velázquez. Well documented in a number of collections thereafter, the painting was last recorded as being in the collection of Cardinal Pompeo Aldrovandi of Bologna and Rome in 1724, after which traces of the work are lost.

Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj

Born into a noble family in Viterbo in 1591, Olimpia married and was widowed twice, latterly by Pamphilio Pamphilj, the elder brother of Cardinal Giambattista Pamphilj, later elected Pope Innocent X in 1644. The Pope’s sister-in-law and his reputed lover, Olimpia Pamphilj was one of the most influential figures at the papal court during her brother-in-law’s tenure. Her influence over the pontiff was well-known with one Cardinal, Alessandro Bichi, on the election of Innocent in October 1644, supposedly angrily declaring, “Gentlemen, we have just elected a female pope.”

Eleanor Herman, New York Times best-selling author and writer of a captivating biography of Olimpia Pamphilj, ‘Mistress of the Vatican’ comments: ‘The most powerful and notorious woman of her time, Olimpia Maidalchini was a baroque rock star. Women from all over the Catholic world came to Rome to station themselves outside her palace to cheer as her carriage rolled out. They could not believe that a female from modest beginnings had risen to such heights – running the nation of the Papal States and the Catholic Church, an institution where women were not allowed any power.’ Nicknamed ‘Papessa’ – the ‘lady Pope’, Olimpia effectively controlled appointments at Papal Court with candidates for vacant episcopal roles applying directly to her, and the office typically going to the highest bidder.

In 1645 she received the title Princess of San Martino, a position she used in court to bring considerable wealth to the house of Pamphilj. Her influence subsided somewhat following the recalling by Innocent X of Fabio Chigi from Germany, who subsequently became Pope Alexander VII, however, in the last years of Innocent’s life, she guarded access to him and used her position for her own financial gain.

Having constantly feared being condemned to a convent as a young woman – the fate of many a dowerless young lady of the time – Olimpia was empathetic to the plight of her own sex. Contemporary accounts describe how she gave money to women to save them from this fate, delivering provisions to convents and building hundreds of homes as dowries for girls who would otherwise not be able to marry and would be forced into a convent or prostitution. She was also said to have allowed prostitutes in Rome to ride in carriages bearing her coat of arms to indicate that they were under her protection.

Olimpia was also a patron of Roman culture sponsoring numerous artists, musicians, playwrights and sculptors and was responsible for Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in the Piazza Navona in Rome designed and created for Pope Innocent X in 1651.

The Discovery

ThePortrait of Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj was last documented alongside Velázquez’s celebrated portrait of her grandson, Cardinal Camillo Massimi, in the collection of Cardinal Pompeo Aldrovandi (1668 – 1752) of Bologna and Rome, in 1724. While the subsequent ownership of Camillo’s portrait is well-documented through to its current location in Kingston Lacy, Dorset, records of the portrait of Olimpia end with Aldrovandi.

The only clue to its whereabouts for almost 300 years before it re-appearance at a Dutch auction house in 1986, is an old custom stamp on the reverse of the former stretcher, indicating that the painting had left Italy in 1911. Brought to the attention of Sotheby’s specialists in Amsterdam who immediately recognised the mysterious cypher on the back of the painting as that of Don Gaspar Mendez de Haro y Guzman, 7th Marques del Carpio, the process of establishing the true creator of the work began in earnest.

Viewing the painting and tracking down various inventories from the 17th and 18th centuries, Sotheby’s Senior Specialist, James Macdonald, soon suspected that this striking portrait could be the hitherto missing original by Velázquez. Showing the painting to key experts in the field, the attribution of the work was confirmed, making the portrait one of only a handful of paintings by the great Spanish artist left in private hands.

Another great discovery: a rare, long-lost drawing by Rosso Fiorentino.

Scrolling through a batch of images sent through from around the world via Sotheby's online valuation tool Cristiana Romalli, Senior Director and Italian specialist in Sotheby’s Old Master Drawings Department, paused at an intriguingly accomplished sketch. It looked to her like an accomplished work by major Mannerist artist, Rosso Fiorentino, whose drawings are extremely rare.

Cristiana retired home to read Giorgio Vasari’s ‘Lives of the Artists’, chronicling the lives of the leading Italian artists of the early 16th-century. And there she found a reference to this work, since then unrecorded – lost from the canon of art history.

Vasari describes how, in 1524, Rosso set out from Florence to Rome, in search of work. He stopped en route in his home town of Arezzo, where he caught up with his old friend Antonio Lappoli (1492-1552). Lappoli – a less successful artist than Rosso – had just been asked to complete a major commission in Arrezzo: a rendering of the Visitation, for the family chapel of a wealthy Aretine citizen. Lappoli turned to his friend Rosso for help and inspiration, and Rosso, forever generous, worked up this beautifully accomplished composition, which Lappoli then used as the basis for his painting.

The beautiful drawing by Rosso – described by Vasari asmolto bello – was believed by scholars to be lost. Its re-emergence now adds significantly to our understanding of the working methods of an artist known for his eccentricity, and expressive, unconventional style. Only the second drawing by Rosso to have appeared on the market in over half a century, its survival and fine state of preservation is nothing short of miraculous.

That it has clearly been handled with care over the last 500 years is perhaps largely thanks to an old attribution to Michelangelo, penned on the back of the drawing in a 17th-century hand; partly too because it has enjoyed the lucky fate of having, since the 18th century, just one careful family of owners. Watch Cristiana Romalli talk about the process of discovery here. The drawing will be offered as a highlight of Sotheby’s Old Master and British Works on Paper sale on 3 July.

.jpg)

View Slideshow

View Slideshow