This November, Sotheby’s will present A Legacy Reimagined, the latest offering of works from The Collection of Dorothy and Roy Lichtenstein. Marking the culmination of a year-long, landmark series of sales that began in New York in November 2024 and traversed London, Paris, Hong Kong and beyond, this sale will take place at Sotheby’s new home in the iconic Breuer building on Madison Avenue — the former site of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Fittingly, it was within these very walls that Roy Lichtenstein’s 1981 mid-career retrospective cemented his place among the giants of twentieth-century art.

One work featured in that exhibition, the painting Cubist Still Life with Vase and Flowers (est. $4-6 million), will anchor the sale, bringing the artist’s dialogue with the Breuer full circle. Now, more than four decades later, the building once again becomes the stage for a defining moment in his legacy. The sale will also feature Brushstrokes (est. $4-6 million), one of Lichtenstein’s most spirited sculptures, which will be installed at the Southwest Corner of 3 World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan ahead of the auction. This dynamic installation extends Lichtenstein’s presence across the city — from uptown at the Breuer to downtown at the Word Trade Center — underscoring his enduring impact on New York’s cultural and architectural landscape. Encompassing paintings, sculptures and works on paper that span the breadth of his career, A Legacy Reimagined brings to a close a year of extraordinary discovery and reflection on one of the most influential artists of the modern era. The sale is estimated to achieve in excess of $30 million, and follows the white-glove results achieved for all works offered from the estate at Sotheby’s since November 2024. The running total for the collection stands at $128.3 million - surpassing the combined pre-sale estimate of $60.1 - 87.5 million.

“To showcase these extraordinary examples of Lichtenstein’s work at the Breuer is to place them within one of the great modernist settings of our time — a fitting context for an artist who redefined modernism itself. The collection’s continued success at Sotheby’s speaks to both the enduring relevance of Lichtenstein’s vision and 3 their mass appeal to collectors the world over. They embody the intelligence, humor, and formal rigor that have made his art an essential part of the cultural imagination” Lucius Elliott, Head of Sotheby’s Contemporary Evening Auctions in New York

Collection Highlights

Cubist Still Life with Vase and Flowers 1973, acrylic, oil, graphite pencil on canvas Estimate $4,000,000 - 6,000,000

To be sold as part of The Now and Contemporary Evening Auction, New York A rare and important work from Lichtenstein’s Cubist Still Life series, Cubist Still Life with Vase and Flowers captures the artist at a pivotal moment of reinvention. Moving beyond his comic-inspired Pop imagery, Lichtenstein turned his focus to the great movements of modern art, beginning with Cubism. The work pays homage to Pablo Picasso, his foremost influence, refracting the visual language of Analytical Cubism through the cool precision of American Pop. Lichtenstein transforms Picasso’s fractured still lifes into crisp geometric forms and bold planes of color, reimagining one of the most recognizable motifs in twentieth-century art. One of only eleven Cubist Still Life paintings created between 1973 and 1975—and the only one to feature a vase of flowers—it stands as a landmark of Lichtenstein’s mature style and his enduring conversation with the art historical canon. In Cubist Still Life with Vase and Flowers, Lichtenstein unites intellect and wit in a composition that is both playful and profound. The artist transforms the traditional still life - long associated with refinement and material identity - into a modern graphic statement of color, line, and form. Floating stems, jagged petals, and fractured backgrounds rendered in Ben-Day dots blur the line between high art and mass culture. Through this witty reconstruction, Lichtenstein honors Picasso’s radical vision while redefining it for a new era. Exhibited internationally, including in the artist’s 1981 mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum’s Breuer Building, the painting stands as a quintessential example of Lichtenstein’s ability to transform art history itself into art.

Brushstrokes Conceived in 1996 and cast in 2001, painted aluminum Estimate $4,000,000 - 6,000,000

To be sold as part of The Now and Contemporary Evening Auction, New York Brushstrokes stands among Lichtenstein’s most iconic and exuberant monumental sculptures, translating one of his signature motifs into three dimensions. Reimagining the dynamic sweep of a painted gesture as solid form, 4Lichtenstein transforms the very act of painting into sculptural expression. The work revisits his celebrated Brushstroke paintings of the 1960s - wry commentaries on the heroic gestures of Abstract Expressionism - now elevated into space as a vibrant composition of color, line, and motion. The sculpture’s powder-blue arc, streaked with emerald, yellow, and white, seems to defy gravity, capturing both the rhythm and humor of Lichtenstein’s lifelong inquiry into the mechanics of artmaking. One of only two examples from the edition, the other held by the Portland Art Museum, Brushstrokes exemplifies the artist’s ability to reframe the language of modernism with wit, clarity, and conceptual brilliance. In Brushstrokes, Lichtenstein turns an essential gesture of painting into an object of playful contradiction. His painted aluminum planes evoke the weightless energy of pigment while remaining rooted in sculptural mass, challenging the very definition of form and space. As critics have observed, Lichtenstein “draws in space,” much like Picasso, using color and contour to suggest motion rather than volume. The result is both cerebral and joyful— a monument to the act of creation and a parody of artistic heroism. With its vivid palette and graphic immediacy, Brushstrokes blurs the boundary between image and object, making the world itself a kind of canvas. Monumental in scale and deeply self-reflective, it stands as one of the most compelling summations of Lichtenstein’s career-long exploration of art’s relationship to its own making.

Modern Painting Triptych II 1967, acrylic, oil, graphite pencil on canvas (three joined panels) Estimate $3,500,000 - 4,500,000

To be sold as part of The Now and Contemporary Evening Auction, New York A striking synthesis of geometry, color, and architectural rhythm, Modern Painting Triptych II captures Lichtenstein’s fascination with the language of modernity. Translating the Art Deco dynamism of New York’s skyline into his bold Pop vernacular, the work unfolds in interlocking fields of scarlet, yellow, and ultramarine. One Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstrokes, installed at 3 World Trade Center Plaza 5 of only six multipanel compositions from the Modern Paintings series, it bridges Lichtenstein’s early Pop iconography and his later investigations of structure and seriality. Drawing inspiration from Mondrian and van Doesburg while parodying the optimism of early Modernism, Modern Painting Triptych II transforms the visual codes of its era into a vibrant meditation on art, architecture, and the enduring pulse of the modern city.

Reflections on Brushstrokes 1990, acrylic, oil and graphite on canvas Estimate $1,200,000 - 1,800,000

To be sold as part of the Contemporary Day Auction, New York Brilliantly reimagining one of his most iconic motifs, Lichtenstein’s Reflections on Brushstrokes transforms the expressive gesture of painting into a layered meditation on perception and artifice. Part of the artist’s celebrated Reflections series, the work fractures his familiar brushstroke through mirrored planes, diagonal bars, and embossed textures, creating a dazzling interplay of surface and illusion. In revisiting the brushstroke nearly three decades after his Pop satires of Abstract Expressionism beginning in the 1960s, Lichtenstein turns parody into introspection, making both artist and spectator part of the act of seeing. Exhibited internationally, including in his landmark 1993–96 retrospective, Reflections on Brushstrokes stands as a luminous statement of Lichtenstein’s late-career mastery and his enduring dialogue with modern art’s visual language.

Archaic Head 1988, patinated bronze Estimate $600,000 - 800,000

To be sold as part of the Contemporary Day Auction, New York Commanding in scale and elegant in form, Archaic Head exemplifies Lichtenstein’s ability to translate the weight of art history into the crisp visual language of Pop. Cast in patinated bronze, the sculpture reimagines the timeless gravitas of an ancient bust through bold contours, schematic planes, and a polished, graphic surface. The result is both monumental and witty - a Pop monument to antiquity. Bridging the classical and the contemporary, Archaic Head captures Lichtenstein’s late-career mastery of transforming enduring cultural symbols into images of modern invention.

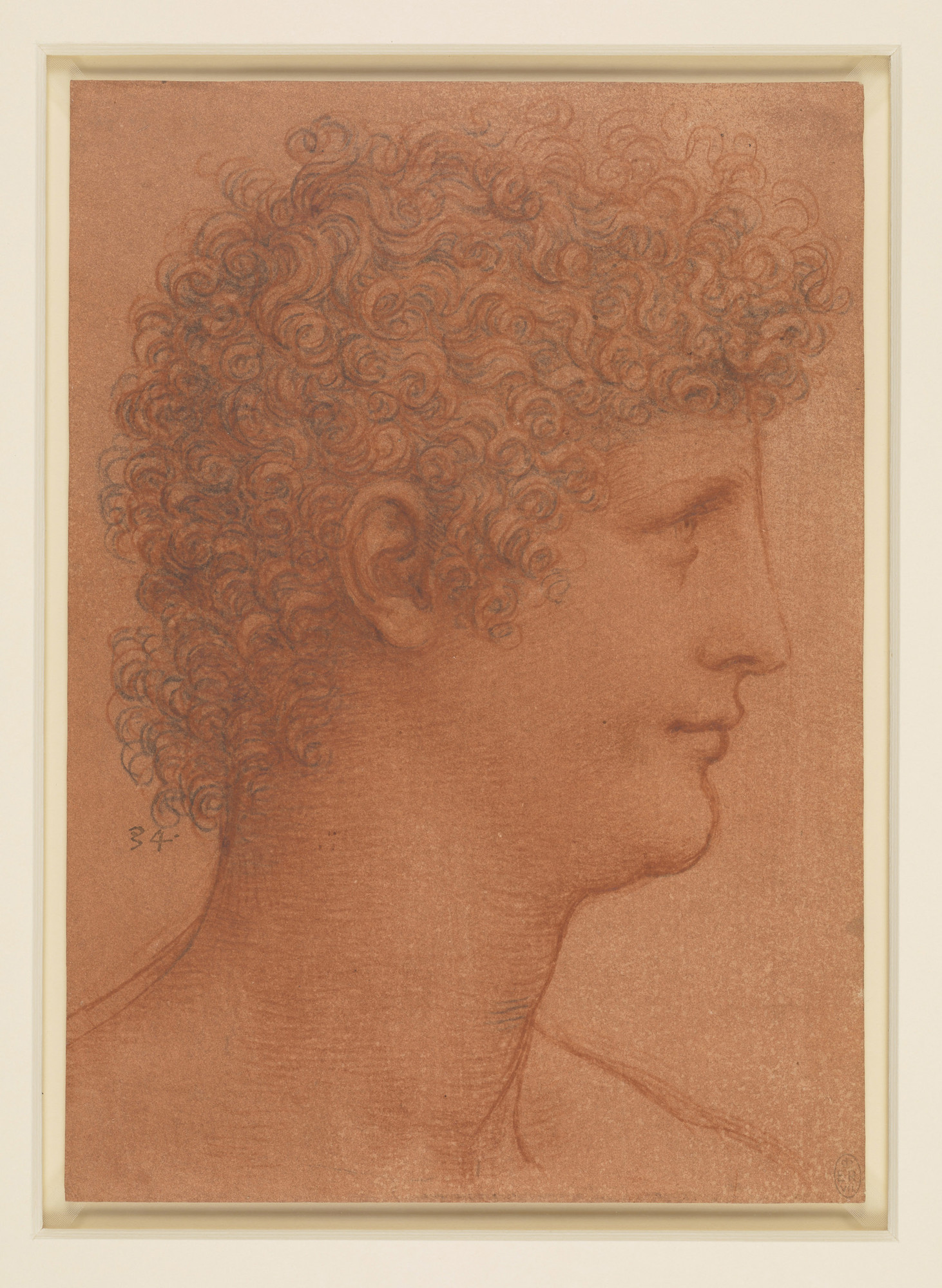

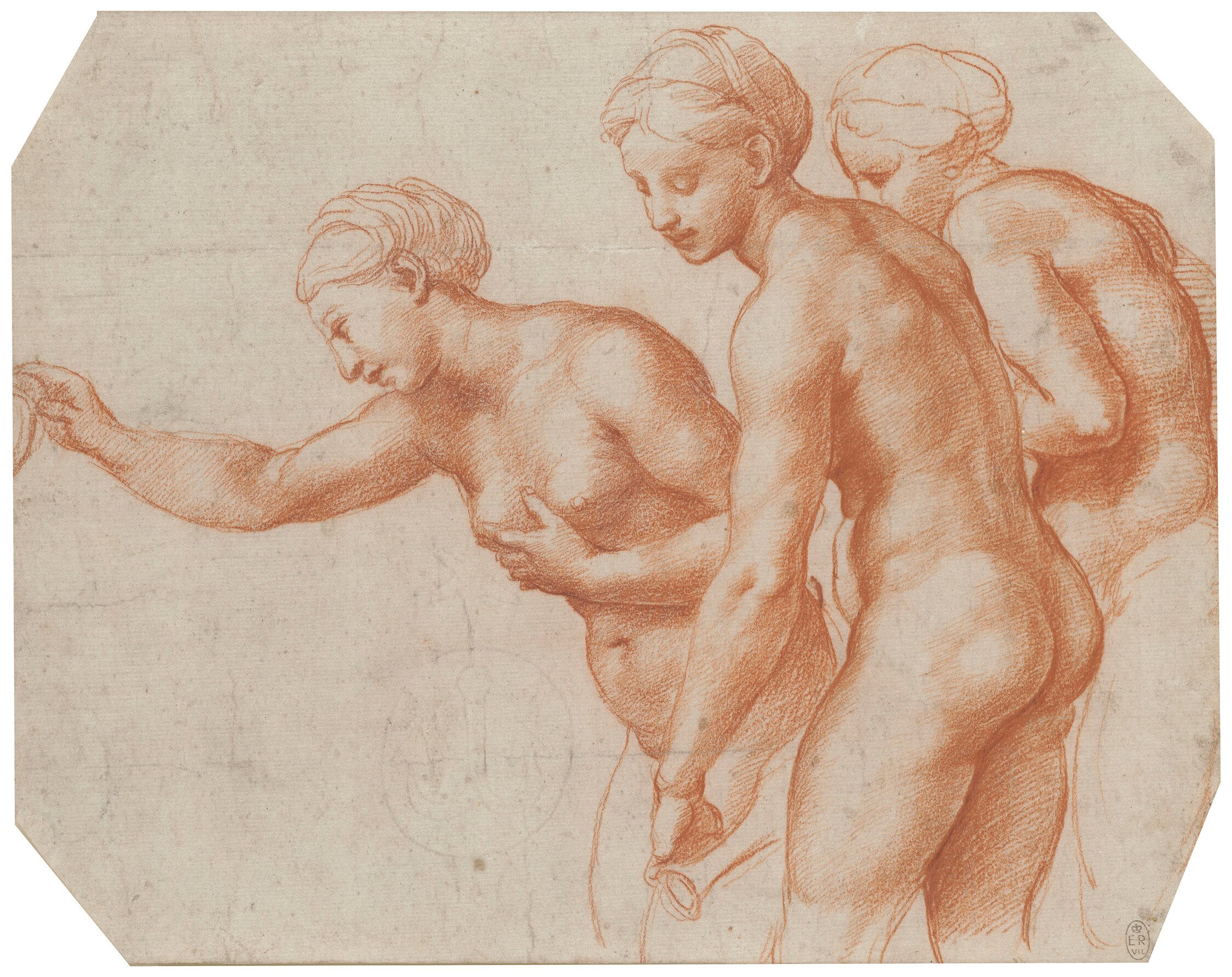

The drawing is a study for the group of the Graces sprinkling a libation over the married couple in the Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche, one of two large scenes frescoed in the vault of the garden loggia of Agostino Chigi's villa on the banks of the Tib

The drawing is a study for the group of the Graces sprinkling a libation over the married couple in the Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche, one of two large scenes frescoed in the vault of the garden loggia of Agostino Chigi's villa on the banks of the Tib