ARTISTS

Beckmann, Max

Dix, Otto

Feininger, Lyonel

Gerstl, Richard

Grosz, George

Heckel, Erich

Kandinsky, Wassily

Kirchner, Ernst Ludwig

Klee, Paul

Kokoschka, Oskar

Kubin, Alfred

Macke, August

Marc, Franz

Mueller, Otto

Nolde, Emil

Pechstein, Hermann Max

Schiele, Egon

Schmidt-Rottluff, Karl

Realism and abstraction are frequently cast as

opposing forces in modernism’s developmental narrative. For reasons that

had to do less with art-historical inevitably than with geopolitics,

abstraction was declared victorious in the United States after World War

II. Reflecting wartime alliances, American abstraction traced its

lineage to France, while the Germanic tradition of figural Expressionism

was largely sidelined. To the extent that Germany’s contributions to

modernism were acknowledged, Munich’s

Blaue Reiter group, which

experimented most overtly with abstraction, received greater attention

than the comparatively representational work of artists based elsewhere

in German-speaking Europe. Wassily Kandinsky’s esoteric theories,

endorsed by Galka Scheyer on the West Coast and Hilla Rebay at the

fledgling Guggenheim Museum (originally the Museum of Non-Objective

Painting) in New York, seemed to affirm the formalist dogma that

dominated the American art world in the third quarter of the twentieth

century.

However, neither Kandinsky nor his Expressionist

colleagues in Germany and Austria believed that art should be free of

all extrinsic content, or as the critic Clement Greenberg put it, that

an artist should be concerned solely with the “arrangement of spaces,

surfaces, shapes, colors, etc., to the exclusion of whatever is not

necessarily implicated in these factors.” In the

Blaue Reiter Almanac,

Kandinsky described two fundamental formal approaches, “the great

realism” and “the great abstraction,” both of which, he said, ultimately

serve the same end: to express “the inner resonance of the thing.” The

German critic Paul Fechter, who authored the first book on the subject

in 1914, similarly identified two strands of Expressionism: the

“extensive,” which retains ties to recognizable subject matter, and the

“intensive,” which entirely renounces such imagery. Whether realist or

abstract in their orientation, Expressionists were driven by a need to

re-envision the world.

Germany and Austria industrialized

relatively late and, unlike England and France, had failed to establish

effective democratic institutions to channel the concomitant social

upheaval. Artists coming of age in German-speaking Europe at the dawn of

the twentieth century objected equally to the rigidity of the old

aristocratic order and to the materialism associated with bourgeois

capitalism.

Inspired by the Nietzschean ideal of human perfectibility,

the North-German

Brücke group hoped to build a “bridge” to a

better future by uniting “the entire younger generation” in opposition

to “entrenched and established tendencies.” For the most part,

first-generation Expressionists eschewed political solutions, instead

focusing on spiritual self-improvement. “When religion, science and

morals…are in danger of failing,” Kandinsky observed, “man turns his

eyes away from the exterior world, onto himself.” At the same time, many

Expressionists sought a connection to universal forces beyond the self,

situated in nature, the infinite or the occult.

Although

Germany’s component principalities made remarkable contributions to the

fields of music, literature and philosophy prior to national unification

in 1871, the territory as a whole had historically ceded artistic

leadership to France. The chain of “isms” emanating from the French

capital—Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, Cubism,

“Primitivism”—continued to inform Germanic modernism, but the German

responses were nonetheless distinct. Whereas French artists tended to

deconstruct their subjects aesthetically, the Expressionists attacked

them metaphysically.

The French (with the notable exception of Paul

Gauguin) responded to “Primitivism” in largely formal terms, while

German artists sought an Edenic ideal in cultures untouched by the

forces of modern civilization. Symbolism—a multinational movement that

attempted to find objective visual correlatives for subjective

states—had a far more profound impact in German-speaking Europe than in

France.

Germans and Austrians proved especially receptive

to fin-de-siècle ideas that revealed, or purported to reveal, the truth

behind surface appearances. Kandinsky equated the discovery of subatomic

particles with the literal dissolution of matter. X-rays, which make it

possible to see through solid objects, came to be associated with

clairvoyance. The physicist Ernst Mach contended that there is no real

difference “between bodies and sensations . . . between what is without

and what is within, between the material world and the spiritual world.”

Enormously popular in German-speaking Europe, Theosophy posited that

the “astral plane” could be accessed through a “subtle invisible essence

or fluid” that radiates from all living beings. Artists were

encouraged, by such contemporary thinkers as Joséphin Péladan, Karl

Wilhelm Diefenbach and Stanislaw Przbyszewski, to consider themselves

“seers,” possessed of a vision that was spiritual as well as artistic.

Accordingly,

the Expressionists transformed color, line and composition into

vehicles for exploring the mystical, emotional or psychological

underpinnings of their subjects.

Urfarben (the “source colors” of

the rainbow), which had been used by the Neo-Impressionists to

replicate optical effects, lost their connection to observable reality.

Not only are these colors purer and brighter than intermediate mixed

hues, but they carry greater emotional weight, especially when clashing

complementaries are juxtaposed.

“Color,” wrote Kandinsky, “is a means to

exercise a direct influence on the soul.” In his 1810 book,

Zur Farbenlehre

(On the Lessons of Color), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had proposed a

vocabulary of symbolic color equivalencies: red was associated with

beauty, orange with nobility, yellow with goodness, green with utility,

blue with mediocrity and so on. The Theosophists also believed in

mystical color associations, though theirs were somewhat different.

(Blue, for example, connoted purity of thought.) Clairvoyants could

ostensibly see these colors emanating from human bodies as “auras” and

“thought forms”—phenomena painted variously by Kandinsky, Oskar

Kokoschka and Egon Schiele.

Like color, Expressionist line

did not adhere to the strict requirements of realistic verisimilitude.

Japanese woodblock prints and

Jugendstil graphic design, both of

which jettisoned three-dimensional interior modeling in favor of

evocative contours, were decisive influences. The woodcuts of Gauguin

and Edvard Munch, caricatures from the satirical magazine

Simplicissimus,

Medieval religious imagery and tribal carvings added an element of

exaggeration to the mix. German and Austrian artists saw line as an

expressive tool in its own right. Many of them employed jagged, angular

or broken lines and bizarre striations for emotional effect. Some aimed

for concision and economy of means, while others retraced outlines

repeatedly to arrive at a quintessential form.

Drawing the moving figure

was a practice common among the

Brücke artists in Dresden, as

well as Schiele and Kokoschka in Vienna. These men all sought to capture

spontaneous visual responses, what Ernst Ludwig Kirchner called “the

ecstasy of first sight.” Kandinsky, on the other hand, developed a more

cerebral language of symbolic lines.

Whether approached in

aesthetic or metaphysical terms, line constituted a crucial boundary

between figure and ground, subject and surrounding cosmos. From Gothic

woodcuts to

Jugendstil design, many of the sources that

influenced the Expressionists treated positive and negative space

equally. The resultant two-dimensional flattening of the picture plane

was especially well suited to landscapes, whose components (buildings,

sky, trees, mountains, etc.) can readily be reduced to abstract shapes.

By visually uniting these elements, artists conveyed a sense of mystical

harmony with and within the natural or human-built environment. Lyonel

Feininger and Schiele each interpreted (or misinterpreted) Cubism in

this vein. Kandinsky, who between 1910 and 1913 gradually relinquished

representational subject matter altogether, equated the picture plane

with infinity or utopia. Fragmentation of form could be used by artists

with a more figural bent to suggest the immateriality of the soul and

the fusion of the body with the spirit realm.

But there is a limit to

how much the human figure can be abstracted and still remain, well,

human. The contrast between artistic representations of “real” people

and the two-dimensional surfaces upon which they “lived” was more likely

to evoke alienation than harmony. For some Expressionists, the line

dividing figure from ground, physical from spiritual, was an impermeable

barrier that only served to highlight the fragility of the self in the

face of a surrounding existential void.

Despite certain

broad affinities among its artists, Expressionism was not a coherent

style in the manner of Impressionism or Cubism. German-speaking Europe

had multiple cultural centers, essentially revolving around its

different art academies. In the final decade of the nineteenth century, a

number of Secession initiatives arose to counter the dominance of those

academies. The Secessions did not espouse specific stylistic programs,

but rather sought to provide exhibition outlets for the rising

avant-garde and to foster international cultural exchange. Collectively,

their aim might be summed up by the motto of the Vienna Secession: “To

the age its art; to art its freedom.”

As a younger generation came to

the fore in the twentieth century, the Secessions foundered.

Nevertheless, they bequeathed to their Expressionist successors a

mandate to pursue the

Kunstwollen—artistic aims—of the time on

their own individual terms. Artists, dispersed among the preexisting

academic centers in such cities as Dresden, Berlin, Munich and Vienna,

took up the challenge in disparate ways.

Die Brücke,

established in Dresden in 1905, was the first and, initially, the most

cohesive Expressionist group. Its founding members, Kirchner, Erich

Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl, were former architecture

students at the Dresden Technical Institute, and though the curriculum

there covered drawing, only Kirchner, who spent one semester at a

progressive studio school in Munich, had any dedicated fine arts

training. Kirchner brought back from Bavaria an appreciation for

Jugendstil

graphics and Gothic woodcuts, as well as an interest in primeval

cultures, which was soon affirmed by the Oceanic and African art in the

Dresden ethnographic museum. This yearning for the “primitive” would

take Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein (both of whom joined

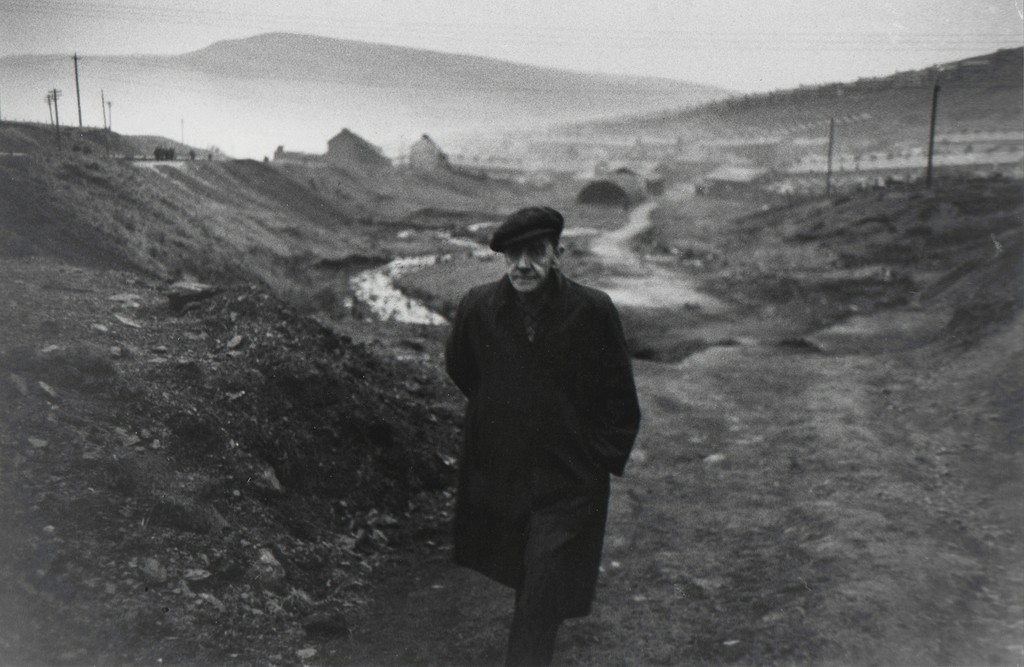

Die Brücke in 1906) to the South Seas in 1913-14, and Otto Mueller (a member from 1910-13) to the Balkans in the 1920s.

At first the

Brücke

artists attempted to create a refuge from modern civilization in their

own backyard. Working communally in a storefront studio, they endeavored

(in Kirchner’s words) “to bring art and life into harmony with one

another.” During the warmer months, they decamped to the countryside,

where they pursued a shared resolve to “study the nude in free

naturalness.”

Printmaking was central to the

Brücke initiative,

both in forging a collective identity and in soliciting financial

support from “passive members,” who were rewarded with an annual print

portfolio. Woodcut, with its melding of Medieval and contemporary

influences, its stark contrasts and exaggerated forms, is the graphic

technique most often associated with

Die Brücke. But the artists

were equally innovative in their etchings and lithographs, transforming

what had been essentially reproductive techniques into original

expressive vehicles.

The group ethos disintegrated after 1911, when

Heckel, Kirchner and Schmidt-Rottluff decided to join Mueller and

Pechstein in Berlin. Leadership conflicts caused

Die Brücke formally to disband in 1913.

While

Germans at the turn of the twentieth century were struggling to cement a

national identity, Austria-Hungary was being torn apart by ethnic,

economic and political tensions across its far-flung empire. There was

little unity among the Austrian Expressionists, little of the utopianism

that marked the Germans’ quest for radical transformation.

Brücke

artists tried to subordinate themselves to a communal ideal; Austrians

were more concerned with redefining the self in the face of intellectual

challenges by such contemporaries as Mach and Sigmund Freud. Kokoschka,

who claimed to have “x-ray vision,” aspired to extract the souls of his

subjects from their external physical shells. Schiele probed his own

persona incessantly, testing the boundary between pretense and essence.

In his oils, Schiele continued a tradition of Symbolist allegory that

owed much to the example of Gustav Klimt. Mortality and human frailty

were recurring themes for both artists.

The

Jugendstil-inflected

work of Klimt and the Wiener Werkstätte strongly influenced Kokoschka

and Schiele during their student years, but by 1910 each had emerged

with a distinctive Expressionistic idiom. Kokoschka’s raw, painterly

style derived from artifacts he had seen in Vienna’s ethnographic

museum. Schiele, on the other hand, retained a propensity for elegant

lines and structured compositions that can be attributed to his more

conventional academic training and to Klimt’s lingering impact. From

1910 on, Kokoschka spent considerable stretches of time in Germany,

where he made contact with members of

Die Brücke and

Der Blaue Reiter.

Appropriating the heavier impastos and bolder colors of those

colleagues, he hereafter was frequently classified as a “German”

Expressionist. Although Schiele also exhibited in Germany, he had

little success there. Both geographically and artistically, he remained

isolated in the Austrian environment. Austria’s third great

Expressionist, Richard Gerstl, who committed suicide in 1908, was

totally unknown until his rediscovery in 1931. Independently working his

way through the formal and tonal lessons of Neo-Impressionism, Gerstl

arrived at the first iteration of what was later called “Abstract

Expressionism.”

Less disjointed than the Austrian Expressionists, but more informal that the

Brücke group,

Der Blaue Reiter

was an alliance of international artists who exhibited together in

Germany between 1911 and 1913. Because this period coincided with the

publication of Kandinsky’s most famous theoretical writings, in the

Blaue Reiter Almanac and

On the Spiritual in Art,

his ideas came to be associated with artists whose styles were actually

quite diverse. Kandinsky had moved to Munich in 1896, along with two

other Russian artists, Alexei Jawlensky and Marianne Werefkin. Soon

Kandinsky assumed a leadership position, founding the Phalanx group and

school in 1901, and in 1909, the

Neue Künstlervereinigung (New

Artists’ Association), an alternative to the increasingly conservative

Munich Secession. In addition to the three Russians and Gabriele Münter

(a former Phalanx student), the

NKV pulled into its orbit Feininger, Alfred Kubin, Paul Klee, August Macke and Franz Marc—all of whom later showed with

Der Blaue Reiter.

During the years of their association, the

Blaue Reiter

artists, each in his or her own way, explored the distinction between

what Kandinsky called the “great realism” and the “great abstraction.”

“Primitivism” (here incorporating not just tribal art, but domestic folk

art, the work of self-taught painters like Henri Rousseau, children’s

art and, for Klee and Kubin, the art of the mentally ill) represented

the “great realism”: art without artifice. By emulating untrained

creators,

Blaue Reiter artists hoped to recapture a primordial

innocence that would enable them to reveal their subjects’ “inner

truths.” Marc’s search for an unspoiled, “natural” state of

consciousness prompted him to identify with nonhuman animals and to try

to depict the world through their eyes.

The path to the

“great abstraction” lay beyond nature, in the realm of pure imagination.

Kandinsky was looking for a visual equivalent to music; an art that

would be free of any representational associations. “In color,” Macke

declared, “there is counterpoint, violin, ground bass, minor, major, as

in music.” Klee and Feininger, both trained as violinists, tried to

imbue their art with the emotional immediacy of music. Nonetheless,

neither they nor Kubin, Münter, Jawlensky or Werefkin ever entirely gave

up recognizable imagery. Even Kandinsky, slow to digest his own

philosophical pronouncements, was still painting landscape forms as late

as 1913. He worried that a completely abstract artwork might too easily

be confused with a “necktie or a carpet” pattern—confounding the

essential link to the spiritual. Macke and Marc were the only other

Blaue Reiter

artists to break through, albeit tentatively, to abstraction. When they

perished in World War I, Kandinsky became the sole surviving

non-objective painter among the first-generation Expressionists.

The

Expressionists’ search for spiritual authenticity was an implicit

protest against capitalistic materialism. Nevertheless, after the

carnage of World War I and the political turmoil that followed, their

approach appeared hopelessly bourgeois. Prewar utopianism was

superseded by the practical necessity of dealing with the socioeconomic

problems of the Weimar era. Denounced as self-indulgent and

incomprehensible, abstraction was deemed incapable of addressing these

new realities. The artists who came of age in Germany after 1918,

however, readily adopted the more realistic innovations of their prewar

predecessors.

There was, in fact, considerable stylistic

continuity between the first- and second-generation Expressionists.

Fragmented images, erratic lines and crazed croppings were ideally

suited to Otto Dix’s on-the-spot renderings of trench warfare. These

same tropes were subsequently used by Max Beckmann to convey the sense

of dislocation and unease endemic to Weimar society. Expressive

exaggeration, verging on caricature in the case of Dix and George Grosz,

was a perfect way to critique contemporary decadence. Often the

compositions of all three artists are packed with detail, compressed

into a claustrophobic, flattened space. At other times, isolated figures

are presented as icons of alienation. By means of these formal devices,

each artist was able to transform his subjective experiences into an

emotionally compelling commentary on the human condition.

Expressionism’s most significant legacy lies in the creation of a

pictorial language that amalgamates abstract elements with references to

the visible world.

All Photos courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York:

MAX BECKMANN (German, 1884-1950)

1. Dinner Party

Circa

1919. Woodcut on thin cream laid Japan paper. Signed, lower right, and

inscribed "Probedruck" (trial proof), lower left. 12" x 4" (30.2 x 10

cm). One of six documented trial proofs; probably hand-printed by the

artist. Hofmaier 158/A.

2. The Tall Man

1921.

Etching on cream wove paper, worked over in ink. Signed and dated, lower

right, and inscribed "Luftschaukel (Handprobedruck)" (Air-Swing

[hand-pulled proof]), lower left. 12" x 8 1/8" (30.5 x 20.6 cm). Plate 5

from the cycle

The Annual Fair. Unique proof of the first state,

hand-printed and extensively worked over by the artist in anticipation

of additions and alterations to the plate in the second state. Hofmaier

195/I.

3. Merry-Go-Round

1921. Drypoing on laid

Japan paper. Signed and with Marées Gesellschaft chop, lower right. 20

7/8" x 15" (53 x 38.1 cm). Plate 7 from the cycle

The Annual Fair. From the edition of 75 impressions on this paper. Hofmaier 197/IIBa.

4. Portrait of Irma Simon

1924. Oil on canvas. Signed and dated, upper right. 48" x 23 5/8" (122 x 60 cm). Göpel 235.

5. Reclining Woman

1945.

Pen, ink and pencil on watermarked laid paper. Signed, dated and

inscribed "A," lower right. 13" x 14 1/8" (33 x 35.9 cm). Study for

Afternoon (Göpel 724).

OTTO DIX (German, 1891-1969)

6. Madonna

1914.

Watercolor, gouahce, ink and pencil on thin off-white wove paper.

Signed and dated, lower right; titled and inscribed "Z. 3081," lower

center. 19 5/8" x 16 7/8" (49.8 x 42.9 cm). Pfäffle A/G 1914/2.

7. Trench with House

1915. Pencil on off-white watermarked laid paper. Signed, lower right. 11 3/8" x 8 1/4" (28.9 x 21 cm). Lorenz WK 5.3.19.

8. Grenade Crater in a House

1916. Pencil on heavy tan wove paper. Signed, lower right. 11 1/4" x 11 1/4" (28.6 x 28.6 cm). Lorenz WK 5.3.24.

9. Soldier

Circa 1917. Black chalk on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, upper right. 16" x 5 1/2" (40.6 x 39.4 cm). Lorenz WK 6.4.27.

10. Apotheosis

1919.

Woodcut on off-white wove paper. Signed and titled, lower right;

inscribed "Handdruck" (hand-pulled print), lower left. 11 1/8" x 7 7/8"

(28.3 x 20 cm). One of a few hand-pulled proofs before the edition of 30

impressions published in 1922. Karsch 30/a.

11. Street Noise

1920.

Woodcut on white wove paper. Signed and dated, lower right, and titled,

lower center; numbered 25/30, lower left. 19 7/8" x 9 1/4" (50.5 x 23.5

cm). Plate 4 from the portfolio

Woodcuts II: 9 Woodcuts. From the edition of 30 impressions. Karsch 26/Bb.

12. Reclining Female Semi-Nude

1929. Red crayon on thin cream wove paper. Signed, upper right. 12 1/4" x 17 5/8" (31.1 x 44.8 cm). Lorenz NSk 12.3.3.

13. The Madam

1923.

Color lithograph on beige laid paper. Signed, lower right, and numbered

64/65, lower left. 19" x 14 1/2" (48.3 x 36.8 cm). From the edition of

65 impressions. Karsch 69/II.

14. Mediterranean Sailor

1923.

Lithograph on heavy smooth off-white wove paper. Signed, lower right,

and numbered 4/55, lower left. 18 1/2" x 12 1/2" (47 x 31.8 cm). From a

total edition of 55 impressions. Karsch 59/b.

RICHARD GERSTL (Austrian, 1883-1908)

17. Nude in Garden

1908. Oil on canvas. Estate stamp, verso. 47 5/8" x 39" (121.1 x 99.1 cm). Kallir 48. Private collection.

GEORGE GROSZ (German 1893-1959)

18. Eccentric Dance

1914.

Pencil on thin cream laid Velin paper. Titled, lower center. Estate

stamp, no. 5-183-6, verso. 11 3/8" x 8 7/8" (29 x 22.5 cm).

19. Reclining Female Nude with Upraised Head

1927.

Pencil on heavy tan wove paper. Signed, lower right, and inscribed

"III/27," upper right corner. 12 3/8" x 17 3/8" (31.4 x 44.1 cm).

WASSILY KANDINSKY (French (Born Russian), 1866-1944)

29. Archer

1908-09.

Colored woodcut on cream watermarked laid paper. Signed, lower rgiht. 6

1/2" x 6" (16.5 x 15.2 cm). Roethel 79. Private collection.

30. Small Worlds

1922.

Portfolio of twelve prints (six lithographs, four drypoints, and two

woodcuts). Title page dedicated to Ilse and Walter Gropius, lower left.

Individual prints signed, lower right. 10 1/2" x 11 7/8" (26.7 x 30 cm).

From the edition of 230 portfolios published by Propyläen-Verlag,

Berlin, 1922, and printed by the Staatliches Bauhaus, Weimar. Private

collection.

ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER (German, 1880-1938)

32. Archer in Moritzburg (Erich Heckel)

1909.

Pen and ink on brownish paper. Estate stamp and registration numbers, "F

Dre/Bf 6," "C 2110" and "K 4901," verso. 17 1/4" x 13" (43.8 x 33 cm).

Registered with the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern,

Switzerland.

33. Dance Group (Three Dancers)

Circa

1910. Pencil on cream wove paper. Numbered 15, verso. 8 1/4" x 6 1/4"

(21 x 15.9 cm). Registered with the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive,

Wichtrach/Bern, Switzerland.

34. Man and Woman Dancing

Circa

1916. Graphite on thin off-white wove paper. 6 3/8" x 7 7/8" (16.2 x 20

cm). Registered with the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern,

Switzerland. Formerly collection Robert Lehman.

35. Fanny in Armchair (Fanny Wocke)

1916.

Lithograph on thin yellow wove paper. Signed, lower right, and

inscribed "Handdruck" (hand-print), lower left. Titled "Fanny" and with

estate stamp and registration number, L450, verso. 23 1/4" x 19 3/4" (59

x 50 cm). One of seven known impressions; hand-printed by the artist.

Gercken 813.

36. Making Hay

1924. Drypoint in brown

on heavt white wove paper. Signed and numbered "111," lower right;

titled and dated, lower center. Estate stamp and registration number, R

489 II, verso. 11 3/4" x 9 7/8" (29.8 x 25.1 cm). One of six known

impressions. To be included in Volume VI of Günther Gercken's catalogue

raisonné; 1466/II. Dube R. 510.

OSKAR KOKOSCHKA (Austrian, 1886-1980)

38. Wiener Werkstätte Postcards

1906-08.

Five color lithographs on heavy card stock. Each 4 7/8" x 3 1/8" (12.1 x

7.9 cm). Published by the Wiener Werkstätte. Wingler/Welz, 3, 4, 14, 15

and 17.

39. The Dreaming Youths

1908. Illustrated

book with eight color lithographs and three line engravings. Numbered

XII inside back cover. 9 5/8" x 11 3/4" x 3/8" (24.4 x 29.8 x 0.9 cm).

One of 275 copies (from a total of 500 printed by the Wiener Werkstäyye

in 1908) published in 1917 by Kurt Wolff. Wingler/Welz 22-29.

40. Sleeping Woman in a Deck Shair (Alma Mahler)

1913.

Red crayon on thin tan wove paper. Initialed, lower left. 13 5/8" x 8

7/8" (34.6 x 22.5 cm). From a series of drawings of Alma Mahler on a

balcony in Naples. Weidinger/Strobl 521.

41. The Last Judgement

1913.

Chalk, pen and ink on thin cream tracing paper. Initialed, lower right.

14 3/4" x 11 5/8" (37.5 x 29.5 cm). Study for the lithograph

Columbus in Chains (Wingler/Welz 45). Weidinger/Strobl 531.

ALFRED KUBIN (Austrian, 1877-1959)

42. Saint Christopher

Circa 1912-15. Pen and ink on buff laid paper. Signed, lower right, and titled, lower left. 14 1/8" x 10 3/8" (35.9 x 26.3 cm).

43. Witches' Sabbath

1918.

Pen and ink on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower rgiht, and titled

"Walpurgisnacht," lower left. 10 1/4" x 14 1/8" (26 x 35.9 cm).

AUGUST MACKE (German,1887-1914)

44. Greeting

1922.

Linocut on heavy beige wove paper. Bauhaus blindstamp, lower left edge.

Inscribed "August Macke: Begrußung" by Elisabeth Macke, verso. 9 5/8" x

8 7/8" (24.4 x 22.5 cm). Plate 8 from the portfolio

Bauhaus Prints: New European Graphics, publihed by Staatliches Bauhaus, Weimar, 1921.

FRANZ MARC (German, 1880-1916)

45. Fantastic Creature

1912.

Color woodcut on white laid tissue paper. Signed, lower left. 5 3/4" x 8

5/8" (14.6 x 21.9 cm). One of 60 impressions included in the deluxe

edition of

The Blaue Reiter Almanac, published by Reinhard Piper & Co., Munich, 1912. Hoberg/Jansen 24/3. Private collection.

46. The Shepherdess

1912.

Woodcut on cream Japan paper. Stamped "Handdruck vom Originalholzstock

bestätigt" (authorized hand-print from the original wood block) and

signed by Maria Marc, verso. 8 3/4" x 3" (22.2 x 7.6 cm). From the first

edition of 21 known prints. Hoberg/Jansen 29/1.

47. Genesis II

1914.

Woodcut in black, yellow and green on thin off-white laid paper. 9 1/2"

x 7 7/8" (24.1 x 20 cm). Three color print printed from three blocks.

Hoberg/Jansen 42/2.

EMIL NOLDE (German, 1867-1956)

50. Head of an Apostle

1909.

Watercolor and pen and ink on thin watermarked cream wove paper.

Signed, lower right. 10 1/2" x 8 1/4" (26.7 x 21 cm). Authenticated by

Prof. Dr. Manfred Reuther, May 7, 2017.

52. Christ and the Sinner

1911.

Etching on heavy off-white wove paper. Signed, lower right. 11 7/8" x 9

3/4" (30.2 x 24.8 cm). One of 6 impressions in this state.

Schiefler/Mosel R 155/V.

53. Prophet

1912. Woodcut

on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower right, and titled, lower left.

Inscribed "Weihnachten 1937" (Christmas 1937), lower right margin. 12

3/4" x 8 7/8" (32.2 x 22.7 cm). From an edition of between 20 and 30

impressions. Schiefler/Mosel H 110.

54. Woman, Man, Servant

1918.

Etching on heavy white wove paper. Signed, lower right, and titled,

lower margin. 10 3/8" x 8 5/8" (26.2 x 21.9 cm). One of 18 impressions

in this state. Schiefler/Mosel 192/I.

EGON SCHIELE (Austrian, 1890-1918)

60. Two Peasant Women

1908.

Colored crayon on heavy brown wove paper. Initialed and dated, lower

left. Inscribed "Hirschbergen 1908," verso. 6 3/4" x 7 7/8" (17.1 x 20

cm). Kallir D. 246a.

61. Baby

1910. Pencil on tan wove paper. Initialed "S" and dated, lower right. 22" x 14 1/2" (55.9 x 36.8 cm). Kallir D. 392.

63. Study for a Never-Executed Painting

1912.

Watercolor, gouache and pencil o heavy cream graph paper. Initialed and

dated, lower left. 8 1/4" x 11 3/4" (20.8 x 29.7 cm). Kallir D. 1193.

Private collection.

65. Poster for the 49th Secession Exhibition

1918.

Lithograph in black, yellow, and reddish brown on thin yellowish poster

paper. 26 3/4" x 21" (67.9 x 53.3 cm). Kallir G. 15/b.

.