24 November 2015 - 27 March 2016

The Museo del Prado and Fundación AXA are presenting Ingres, the first monographic exhibition in Spain on one of the most important painters in the history of art but an artist who, for complex historical reasons, is not represented in Spanish public collections. For this reason, the present comprehensive reassessment of the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres offers visitors to the Prado a unique and outstanding opportunity to appreciate and analyse this French painter’s relationship with the artistic movements of his day – Neo-classicism, Romanticism and Realism – from which his style and ideology remained resolutely unaffected.Inspired by the Romantic quest for ideal beauty, which for Ingres arose from his fascination with the classical past and with the art of Raphael, he broadened the genres of portraiture, the nude and history painting. Ingres’ remarkable skills as a draughtsman also make him an outstanding exponent of this technique while revealing his ceaseless quest for perfection.

Nonetheless, Ingres’ art defies categorisation, given that he explored all the themes and aesthetic approaches of his time and rejected the hindrances implied by affiliating himself with a particular school, movement or style. His uniqueness is evident in the importance of the role he has played as a key forerunner of the language of the avant-garde movements and abstraction and the influence that he exercised on some of Spain’s most important painters, such as Federico de Madrazo, Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí.

As the generous lender of some of its most important works, the Musée Ingres in Montauban has been crucial for the presentation of this exhibition at the Prado. For this reason and with the collaboration of Acción Cultural Española as the co-organiser of the project, on 3 December and during the time the exhibition on Ingres is on display, the Prado will be exhibiting a series of 11 works from its collections at the Musée Ingres with the aim of offering a survey of portraiture in Spanish art.

The exhibition

Ingres offers a unique chronological survey of the artist’s career as a whole, revealing him in all his splendour. The exhibition thus opens with a seductive self-portrait that conveys his youthful energy, loaned from the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and closes with Self-portrait of Ingres aged 78 loaned from the Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence, a work that transmits the master’s supreme artistic authority in his final years.The exhibition pays close attention to Ingres’ activities as a portraitist, which gave rise to one of the most beautiful chapters of 19th-century art. Perfectly capable of precisely capturing his sitters’ characters, Ingres was able to depict both the imposing presence of an Emperor in the iconic

Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne

and the dreamy nature of an artist in François-Marius Granet from the Musée Granet in France.

All these images reveal an authentic language that arose from the artist’s ongoing dialogue with the portraits he had studied in the Musée Napoleón and the ones he later saw in Italy.

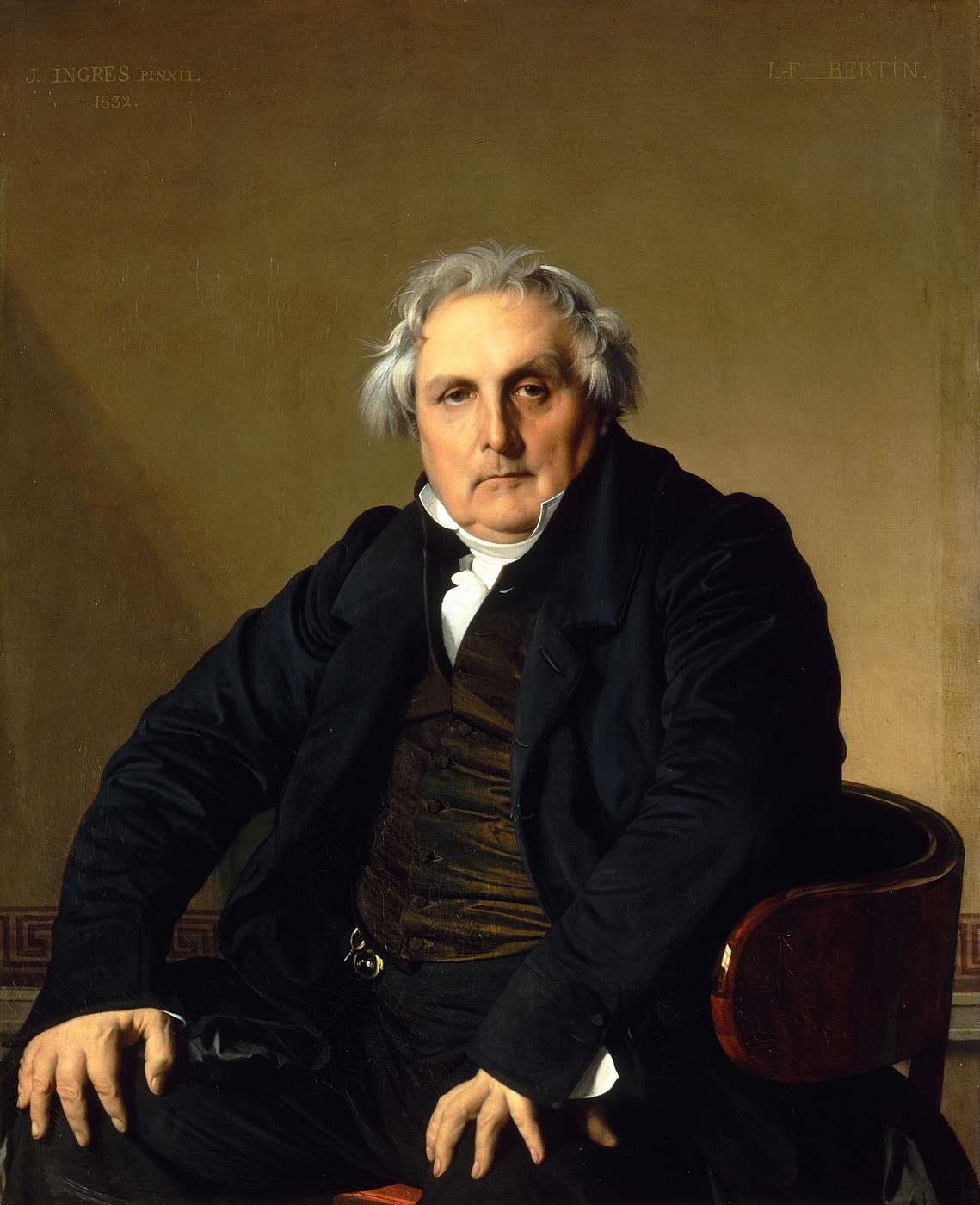

The portrait of Monsieur Bertin, loaned from the Louvre, which is a dynamic image of the fourth estate, or that of the

The Countess of Haussonville. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Oil on canvas, 132 x 92 cm. 1845. New York, The Frick Collection, 1927.

Countess of Haussonville from the Frick Collection in New York offer a superb conclusion to Ingres’ endeavours in this genre.

Displayed alongside these work is a marvelous series of sensual female nudes.

The Grande Odalisque from the Musée du Louvre, an image of pure nudity with no narrative justification, has been one of the most influential images in the history of modern painting.

Ruggiero rescuing Angelica depicts a sensual, voluptuous woman who is a clear paradigm of contemporary eroticism,

while The Turkish Bath from the Louvre, a legendary work that summarizes Ingres’ fascination with repetition, champions the curve as the ideal form for expressing his tireless enthusiasm with the female body, once again located in an exotic context.

This survey of Ingres’ work also includes a focus on his interest in the genre of history painting, represented by works painted in Rome in which the artist measured himself against the power of the myths of Greco-Roman literature and of Homer and Virgil, as in

Virgil reading the Aeneid (loaned from Brussels)

and the Studies for “The Apotheosis of Homer”.

This section also includes examples of Ingres’ “troubadour” paintings in which he gave free rein to his obsession with the artists of the past whom he most admired, including Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci, in works such as

Raphael and La Fornarina (loaned from Ohio) (one of the many versions he produced)

and François I at the Deathbed of Leonardo da Vinci (from the Petit Palais, Paris).

Finally, the exhibition analyses Ingres’ relationship with religious painting, represented in all its variants, from small-scale intimate works such as the moving

Virgin adoring the Host from the Louvre

to monumental compositions such as

Christ among the Doctors.