Sept. 14

through Dec. 30, 2018

Reynolda House Museum of American Art

January - April, 2019

Suzanne H. Arnold Art Gallery, PA

September– December, 2019

Gilcrease Museum, OK

September - December, 2020

Pulaski Tech, AR

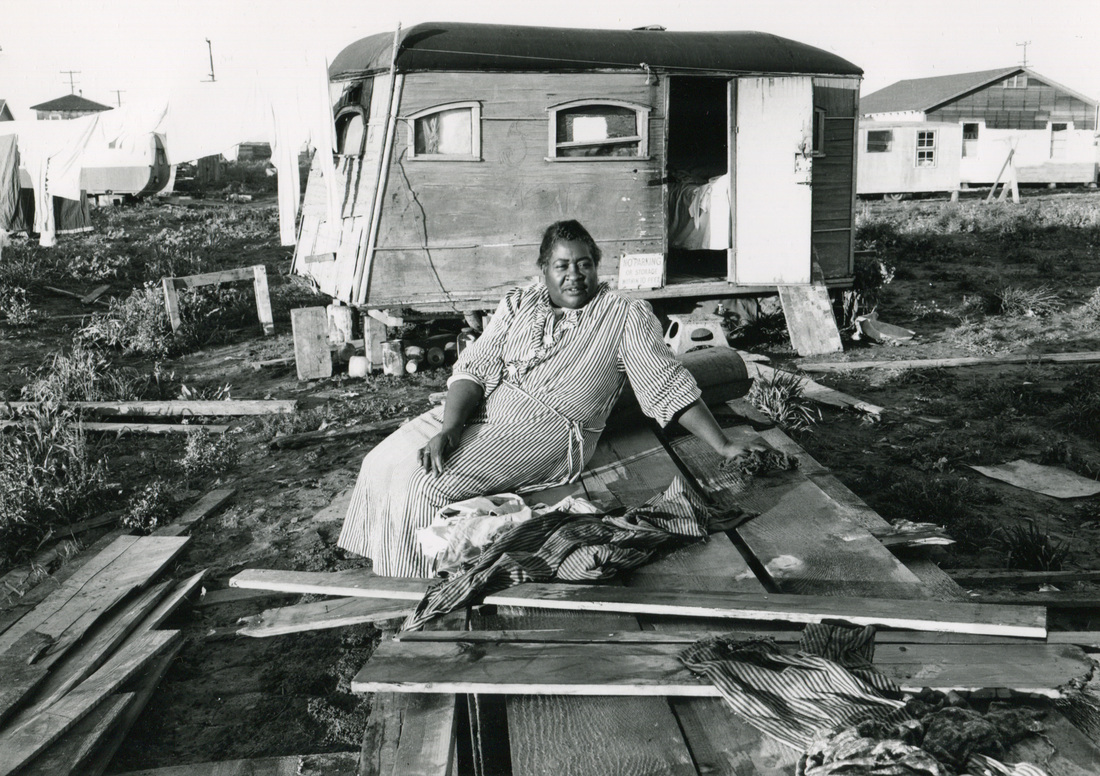

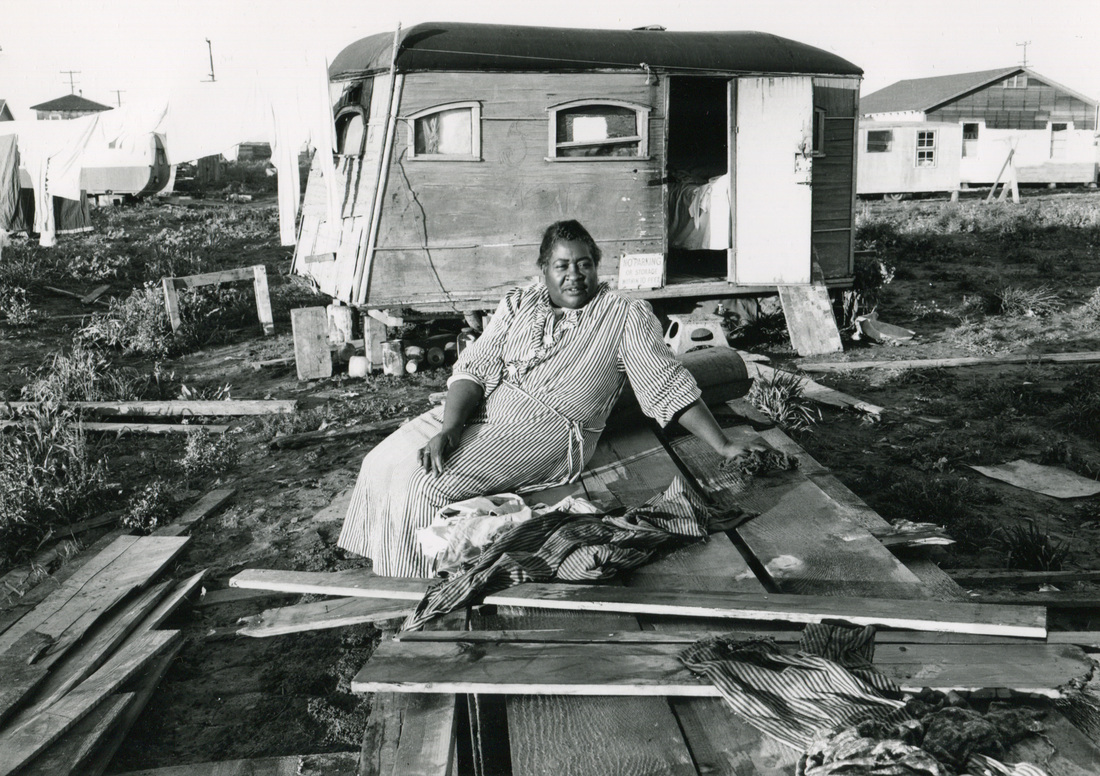

The exhibition, “Dorothea Lange’s America,” presents Lange’s haunting photographs of 1930s and 1940s America and features some of the most iconic images of the 20th century.

“Lange’s documentary photographs appeared in local newspapers, reaching both the masses across middle America and the lawmakers in our nation’s capital, becoming poignant catalysts for social change and, ultimately, highly valued works of art,” says Allison Perkins, Reynolda House executive director. “We identified this exhibition as an opportunity not only to appreciate the artistry of her photographs, but also to draw connections between their subjects and our communities today.”

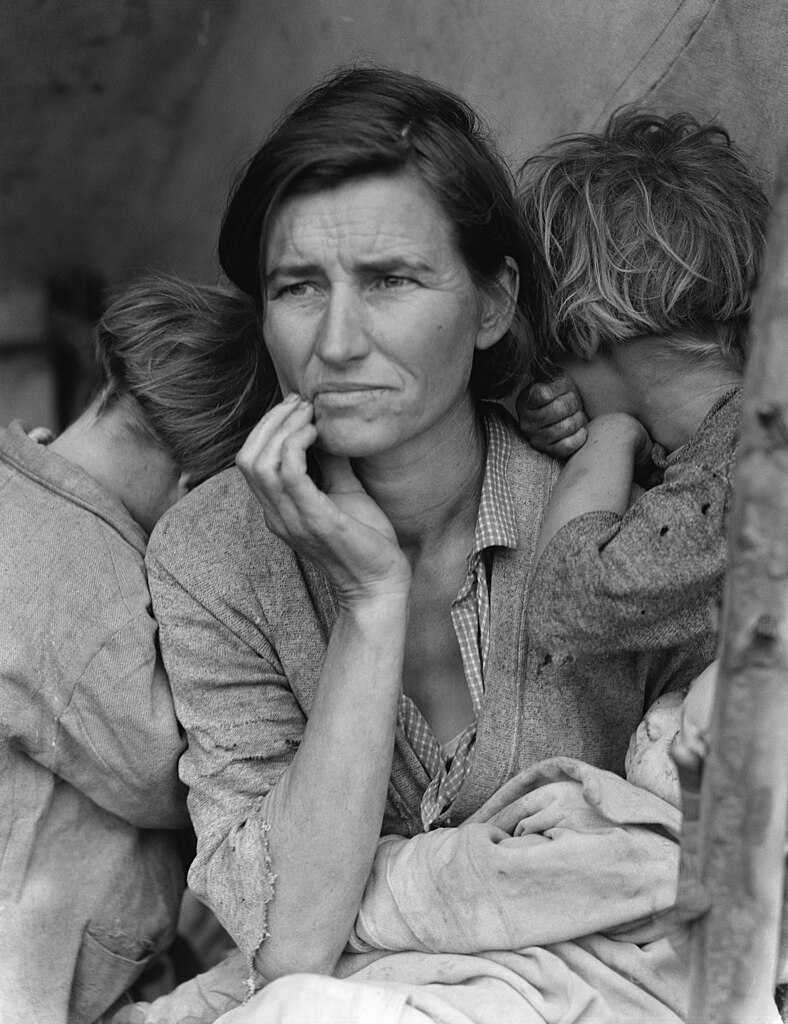

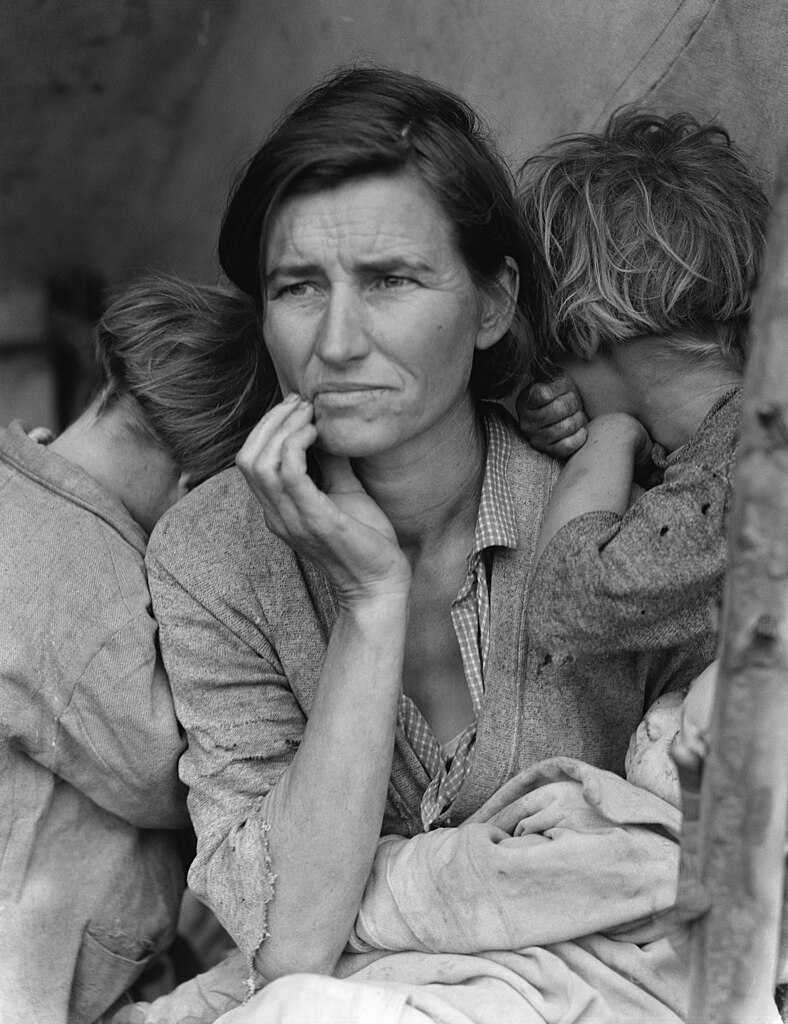

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the most recognizable photograph of Lange’s career, “Migrant Mother,” made in 1936. Recently named the most downloaded photograph in the Library of Congress' archive, it is also one of the most arresting images ever created; its ensuing influence on photojournalism is incapable of measurement. The portrait of Florence Owens Thompson with three of her young children became a visual shorthand for the Great Depression and humanized its consequences for the public at large. Upon its original publication in a San Francisco newspaper, the image ignited a massive benevolent response: 20,000 pounds of food was delivered within days to the migrant camp where the photograph was made.

Lange herself had known adversity early in life. At age 7 she was stricken with polio, which left her with a lifetime limp. And at age 12 her father disappeared from the scene, leaving an impoverished household behind. Every day she would ride the ferry with her mother from Hoboken to lower Manhattan, to a roiling working-class neighborhood teeming with immigrants. During that period Lange talked her way into photo courses with a range of teachers as diverse as Arnold Genthe and Clarence White. In 1918 she moved to San Francisco where she befriended the photographers Ansel Adams and Imogen Cunningham, and, through them, the celebrated Western painter Maynard Dixon, who became her first husband. She soon opened a thriving portrait studio that catered to San Francisco’s professional class and monied elite. But with the crash of 1929 she found her true calling, as a peripatetic chronicler of the many faces of America, old and young, urban and rural, native-born and immigrant, as they dealt with unprecedented hardship, sometimes with resilience, often with despondence. Her immortal portraits seared these faces of the Depression era into America’s consciousness.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art

January - April, 2019

Suzanne H. Arnold Art Gallery, PA

September– December, 2019

Gilcrease Museum, OK

September - December, 2020

Pulaski Tech, AR

The exhibition, “Dorothea Lange’s America,” presents Lange’s haunting photographs of 1930s and 1940s America and features some of the most iconic images of the 20th century.

“Lange’s documentary photographs appeared in local newspapers, reaching both the masses across middle America and the lawmakers in our nation’s capital, becoming poignant catalysts for social change and, ultimately, highly valued works of art,” says Allison Perkins, Reynolda House executive director. “We identified this exhibition as an opportunity not only to appreciate the artistry of her photographs, but also to draw connections between their subjects and our communities today.”

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the most recognizable photograph of Lange’s career, “Migrant Mother,” made in 1936. Recently named the most downloaded photograph in the Library of Congress' archive, it is also one of the most arresting images ever created; its ensuing influence on photojournalism is incapable of measurement. The portrait of Florence Owens Thompson with three of her young children became a visual shorthand for the Great Depression and humanized its consequences for the public at large. Upon its original publication in a San Francisco newspaper, the image ignited a massive benevolent response: 20,000 pounds of food was delivered within days to the migrant camp where the photograph was made.

You

force yourself to watch and wait. You accept all the discomfort and the

disharmony. Being out of your depth is a very uncomfortable thing. You

force yourself onto strange streets, among strangers. It may be very

hot. It may be painfully cold. It may be sandy and windy and you say,

‘What am I doing here? What drives me to do this hard thing?’-- Dorothea Lange

Highlighting this show are oversized exhibition prints of her seminal portraits from the Great Depression, including

Highlighting this show are oversized exhibition prints of her seminal portraits from the Great Depression, including

White Angel Breadline,

and, most famously,Migrant Mother – an emblematic picture that came to personify pride and resilience in the face of abject poverty in 1930s America.

Dorothea Lange

Hands, Maynard and Don Dixon, California, 1930

Hands, Maynard and Don Dixon, California, 1930

Dorothea Lange

Filipinos cutting lettuce, Salinas, California, 1935

Filipinos cutting lettuce, Salinas, California, 1935

Lange herself had known adversity early in life. At age 7 she was stricken with polio, which left her with a lifetime limp. And at age 12 her father disappeared from the scene, leaving an impoverished household behind. Every day she would ride the ferry with her mother from Hoboken to lower Manhattan, to a roiling working-class neighborhood teeming with immigrants. During that period Lange talked her way into photo courses with a range of teachers as diverse as Arnold Genthe and Clarence White. In 1918 she moved to San Francisco where she befriended the photographers Ansel Adams and Imogen Cunningham, and, through them, the celebrated Western painter Maynard Dixon, who became her first husband. She soon opened a thriving portrait studio that catered to San Francisco’s professional class and monied elite. But with the crash of 1929 she found her true calling, as a peripatetic chronicler of the many faces of America, old and young, urban and rural, native-born and immigrant, as they dealt with unprecedented hardship, sometimes with resilience, often with despondence. Her immortal portraits seared these faces of the Depression era into America’s consciousness.

All

works in the exhibition are from the collection of Michael Mattis and

Judith Hochberg. The exhibition was organized by art2art Circulating

Exhibitions.

Great collection of Lange images

Great collection of Lange images