The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza is holding the first retrospective in Madrid on the Belgian artist and leading Surrealist René Magritte (1898-1967) since the exhibition held at the Fundación Juan March in 1989. Its title, The Magritte machine, emphasises the repetitive and combinatorial element present in the work of this painter, whose obsessive themes constantly recur with innumerable variations. Magritte’s boundless imagination gave rise to a very large number of audacious compositions and provocative images which alter the viewer’s perception, question our preconceived reality and provoke reflection.

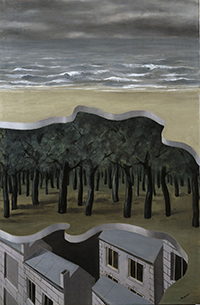

René Magritte. The Dream, 1945. Utsonomiya Museum of Art, Japan

Curated by Guillermo Solana, the museum’s artistic director, The Magritte machine is benefiting from the collaboration of Comunidad de Madrid and features more than 95 paintings loaned from institutions, galleries and private collections around the world, thanks to the support of Magritte Foundation and its president Charly Herscovici. The exhibition is completed with a selection of photographs and amateur films by Magritte himself which is part of a traveling exhibition curated by Xavier Canonne, director of the Musée de la Photographie de Charleroi, and which will now be shown in a special installation. After its presentation in Madrid The Magritte machine will be seen at the Caixaforum in Barcelona from 24 February to 5 June 2022.

My paintings are visible thoughts

In 1950 René Magritte and some of his Belgian Surrealist friends produced a catalogue of products of a supposed cooperative society, La Manufacture de Poésie, which included items intended to automatise thinking and creation, including “a universal machine for making paintings,” described as “very simple to use, within the reach of everyone” and which could be used to “compose an almost unlimited number of thinking paintings.”

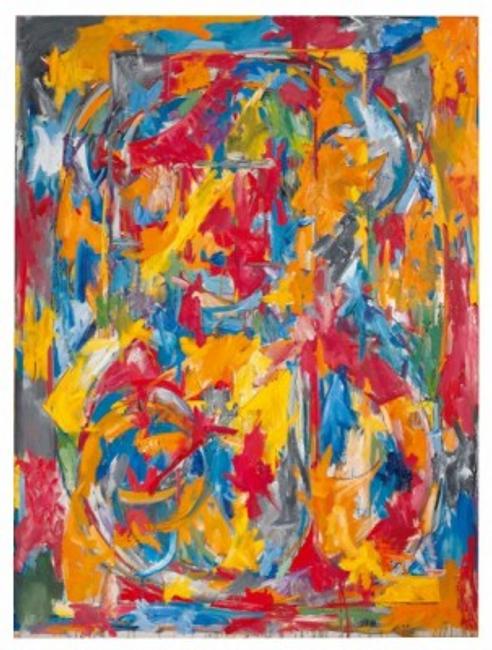

René Magritte. The Anniversary, 1959. Art Gallery of Ontario Collection, Toronto

The painting machine had precedents in avant-garde literature, such as those devised by Alfred Jarry and Raymond Roussel, forerunners of Surrealism whose inventions emphasised the physical process of painting, albeit through opposing concepts: in the former’s the machine revolved and sprayed out jets of paint in all directions, while the latter’s resembled a printer that produced photo-realist images. The device described by the Belgian Surrealists is different and was intended to generate images that were aware of themselves. The Magritte machine is a metapictorial one, a machine for producing thinking paintings and ones that reflect on painting itself.

Since my first exhibition, in 1926 [...] I have painted a thousand paintings, but I haven’t conceived more than a hundred of those images which we’re talking about. These thousand paintings are the result of the fact that I’ve often painted variants of my images: it’s my way of better defining the mystery, of possessing it better.

René Magritte. Personal Values, 1952. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Magritte defined his painting as an art of thinking. Despite his well-known opposition to automatism as a central procedure of Surrealism, he seemed to confer an intellectual value on the de-personalisation and objectivity of that auto-reproduction of his work. The Magritte machine is not coherent and closed in the manner of a system; rather, it is an interactive procedure involving discovery. It is also recursive as the same operations constantly repeat themselves but with different results every time.

All of Magritte’s art is a reflection on painting itself, a reflection it undertakes using paradox as a fundamental tool. What is revealed in a painting, either through contrast or contradiction, is not just the object but also its representation, the painting itself. When painting is limited to reproducing reality, the painting disappears and only reappears when the painter sets everything at odds: painting only becomes visible through paradox, the unexpected, the unbelievable and the odd.

René Magritte. Panorama for the Populace, 1926. Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

In order to achieve this aim Magritte used the classic resources of metapainting, of the representation of the representation (the painting within the painting, the window, the mirror, the figure seen from behind) which become deceptions in his work. The present exhibition analyses these metapictorial devices, which are the guiding thread of the different sections. The first section is entitled “The magician’s powers” and includes various self-portraits which explore the figure of the artist and the superpowers attributed to him. The next section is “Image and word” which focuses on the introduction of writing into painting and in the conflicts generated between textual and figurative signs, followed by the third section, “Figure and background”, which examines the paradoxical possibilities generated by the inversion of the figure and background, silhouette and void. “Picture and window” analyses the painting within the painting, which is Magritte’s most common metapictorial motif, while “Face and mask” focuses on the suppression of the face in the human body, one of Magritte’s most frequently used devices. The two final sections look at opposing processes of metamorphosis, namely “Mimicry” and “Megalomania”. The first introduces Magritte’s fascination with animal camouflage, which he transferred to objects and bodies that conceal themselves in their setting, in some cases dissolving into space, while the final section presents the device of change of scale as an anti-mimetic movement, extracting the object from its normal setting and projecting it outside of any context.

1. The magician’s power

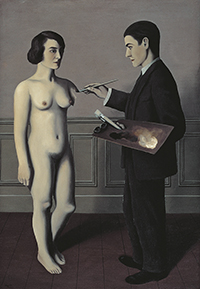

René Magritte. Attempting the Impossible, 1928. Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

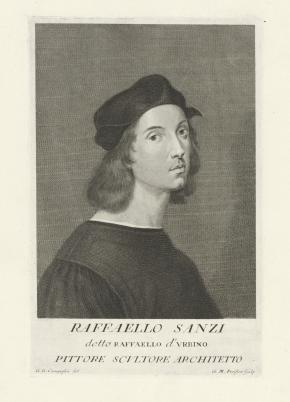

This space brings together three of the four known self-portraits by Magritte in which he explored the potential of the artist as magician while suggesting an ironic attitude towards myths relating to the genius creator. Magritte was not interested in describing his appearance or in recounting his life through these works. His self-portraits are pretexts to introduce the figure of the artist and the creative process into the painting.

In Attempting the Impossible (1928) Magritte is seen painting a naked woman; he is real but she is only the product of his imagination, suspended between existence and nothingness. This is a version of the myth of Pygmalion, of artistic creation identified with desire and with the power of the imagination to produce reality. The Philosopher’s Lamp(1936) presents the encounter between two of the artist’s fetish elements, both of which have sexual symbolism; the nose and the pipe. In The Magician (1951) the painter is seen using his superpowers to feed himself. A group of photographic self-portraits completes this first section in the exhibition.

2. Image and word

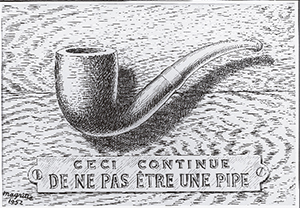

René Magritte. The Treachery of images. This continues not to be a pipe, 1952. Private collection, Belgium

Words were a habitual device employed in Cubist, Futurist, Dadaist and Surrealist paintings and collages. Magritte introduced them into his work during his time in Paris between September 1927 and July 1930 when he was in close contact with the Parisian Surrealist group. During those years he created his tableaux-mots, paintings in which the words combine with figurative images or semi-abstract forms in the case of the early ones while in those of 1928 and 1929 they are shown alone, set in frames and silhouettes and almost always in school textbook handwriting.

In the former, image and word rarely coincide, which disconcerts the viewer and encourages reflection. The important aspect of these works is not the designated objects but the appearance of contradiction between what the image shows and what the text says. The words deny the image and the image denies the words, establishing a separation between the object and its representation. Its supreme paradox is to deny that any paradox exists. When words replace image and become the sole protagonists they are almost always depicted inside a curving surround like a comic book bread roll. Writing reappeared in Magritte’s work in 1931 in replicas or variants of these paintings and only rarely in new inventions.

3. Figure and background

René Magritte. The Amorous Vista, 1935. Private collection, courtesy Guggenheim, Asher Associates

The production of collages and papiers collés is not particularly extensive in Magritte’s output although their influence is evident throughout his painting and thus throughout the exhibition. The first step in making a collage is cutting out and the cut-out generates a large part of Magritte’s images, creating a partitioned, stratified, compartmentalised world of planes that are partly concealed and partly reveal others further back into the pictorial space.

Between 1926 and 1931 the influence of collage became more intense. Magritte’s paintings now became filled with pierced and torn planes and with silhouettes that simulate cut-out paper and stand up vertically like theatrical set elements. In 1927 the artist began to evoke the children’s game of folding and cutting out paper to create chains of repeated geometrical and symmetrical motifs. The result is a sort of lattice, one of those elements which simultaneously reveal and conceal that are so characteristic of the artist.

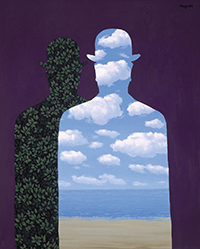

René Magritte. High Society, 1965 o 1966. Fundación Telefónica

Another frequently used device is the inversion of figure and background, making solid bodies into voids or holes through which we see a landscape or an area that is filled with something such as the sky, water or vegetation. The outline belongs to the object not the background and preserves the ghostly presence of the object. Magritte used this play of inversion of figure and background in order to develop his exploration of mimicry, which is the subject of another section in the exhibition.

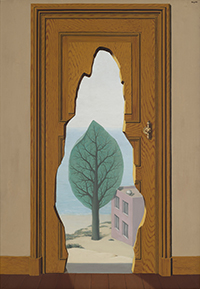

4. Picture and window

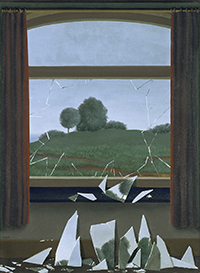

In front of a window seen from the inside of a room I placed a painting that exactly represented the part of the landscape concealed by that painting. Thus the tree represented in the painting concealed the tree located behind it, outside the room. For the viewer, the tree was in the painting inside the room and at the same time, through the mental process, it was outside, in the real landscape. This is how we see the world; we see it outside ourselves but nevertheless we only have a representation of it inside us.

René Magritte. The Key of the Fields, 1936. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

The painting inside the painting is an iconographic theme which on occasions acquired an ambiguous appearance in the work of the Old Masters. Heir to the tradition of trompe l’oeil games, in Magritte’s work it always becomes a ruse and leads to the disappearance of the painting. The artist literally adopted the classical metaphor that compares the painting to a window and took it to its furthest extent: if the painting is a window, the perfect painting would be completely transparent, in other words, invisible. The perfection of the painting consists in it disappearing, and Magritte almost reaches that point then stops. He was not, however, looking for a sudden, permanent disappearance but rather a gradual one that would always leave the viewer doubting if we are really seeing what we think we see.

The exhibition brings together outstanding examples such as The Promenades of Euclid (1955). Here Magritte creates a series of animated frames, one inside the other; the edge of the cloth, the window, the curtains. He thus moves several degrees away from reality. The painting loses its privileges and becomes just one of various framing devices. In The Key of the Fields (1936), a fundamental work that is in the permanent collection of the Museo Thyssen, the painting disappears or rather its powers are transferred to the window, the glass of which ceases to be transparent and mysteriously reveals itself as a painted surface. The painting disappears but it returns in the fragments of glass.

5. Face and mask

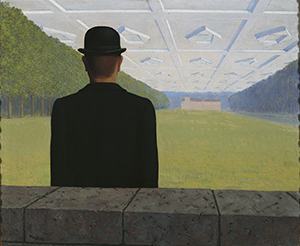

René Magritte. The Great Century, 1954. Kunstmuseum Gelsenkirchen

Since it first appeared in 1926-1927, the figure seen from behind constantly reappears in Magritte’s work and accompanies a wide range of enigmas; with its hidden face it is the perfect silent witness to the mystery. The figure seen from behind dates back to late medieval painting but it only became significant when Friedrich made it the principal motif in his paintings. In the late 19th century Arnold Böcklin revived this Romantic motif as an expression of longing and melancholy and from Böcklin it passed on to Giorgio de Chirico and from him to Magritte.

The figure seen from behind shows us the landscape and how to contemplate it, introducing us into it. The figure’s gaze leads our eyes towards the horizon and encourages the perspectival depth but the figure’s body conceals that gaze from us. The figure from behind makes the viewer aware of the act of looking and the act of contemplation is raised to the power of two. The viewer moves from admiring the landscape to admiring the act of that viewer included in the painting.

With Magritte we also find a recurring symmetry in which a figure seen from behind accompanies another figure seen frontally with the face concealed, which are two completely different ways of hiding the face. This is often done with a white cloth covering the head or in some cases the whole body. The covered head has been related to Magritte’s early fascination with Fantômas, the hero of a series of popular novels whose kept his head covered and whose identity was never revealed, and also with a childhood memory; the suicide of his mother who jumped into a river. When her body was found her head was covered by her nightgown.

René Magritte. Shéhérazade, 1950. Private collection, courtesy Vedovi Gallery, Brussels

The coffins in the Perspectives series can also be seen as a variant on the covered head. In these works Magritte selected various icons of the bourgeois portrait in order to boycott them with his black humour. The title of the series reflects the clairvoyant powers of the painter, who is able to see the sitters in their future state. This are parodic vanitas images, mocking memento mori which laugh at death and the immortality of the great icons of painting.

Pareidolia, in which meaningful images are read into inanimate objects as more or less approximate substitutes of the human face, is a device used by Magritte in Scheherezade (1950) and in the series of nudes framed by their hair.

6. Mimicry

[...] I have found a new possibility things may have: that of gradually becoming something else, an object melting into an object other than itself. [...] In this way I obtain pictures in which 'the eye must think' in a way entirely different from the usual.

René Magritte. The Future of Statues, 1932. Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg

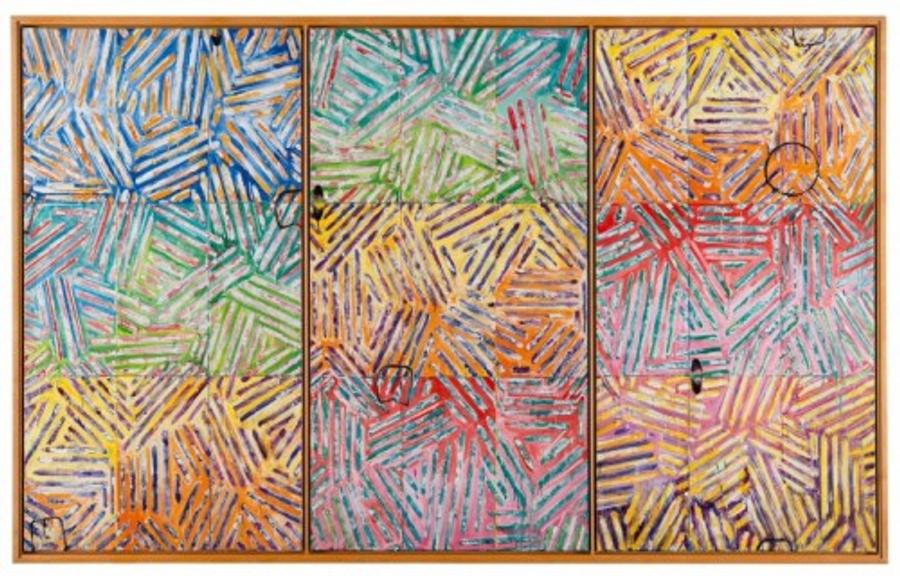

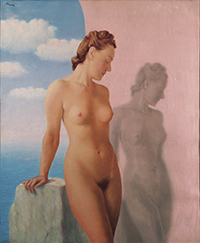

Discovery (1927) marks Magritte’s first use of the method of metamorphosis which later became his most frequently employed approach, particularly during the war. In this painting the mimetic metamorphosis seems to emerge from the body whereas in other works it proceeds from the exterior, from the surrounding space. A body dissolved into the air is also the subject of The Future of Statues (1932), a cast of Napoleon’s funerary mask camouflaged with blue sky and white clouds. Just as death dissolves the self, painting dissolves the volume of the plaster into the blue of the sky. These works anticipate an important series that began in 1934 with Black Magic, in which a woman’s naked body does not disappear as it retains its forms and outlines and rather changes colour. The body becomes chameleon-like and is now located midway between two worlds; flesh and air, land and sky.

In some of my paintings colour appears as an element of thought. For example, a thought made up of a woman’s body which is the same colour as the blue sky.

René Magritte. Sky Bird, 1966. Private collection, courtesy Di Donna Galleries, New York

Magritte was particularly interested in birds, using them to present a wide range of mimetic metamorphoses and transforming them into the sky, as in The Return (1940). In other examples a ship can become the sea, as in the four versions of The Seducer which he painted between 1950 and 1953, in which the barely visible ship is shown as filled with the colour and texture of the waves. Magritte described it as if the elements were living beings: the water imitates the sailing boat and the air imitates the bird, or better said, the water dreams about a boat that is camouflaged as water, the sky dreams about a dove clothed in the sky. The paradox of Magritte’s mimicry lies in the fact that the subordination of the figure to its setting can make that figure more visible, but visible through its absence.

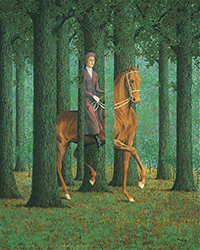

René Magritte. The Blank Signature, 1965. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Magritte’s mimicry can also be seen as a consequence of his interest in inverting the figure and background. The mimetic animal or object changes from being a figure to being background, or they fuse with the background so that they cannot be separated, as in The Blank Signature (1965) in which the rider and her horse blend with the trees just as the visible fuses with the invisible.

If somebody rides a horse through a wood, at first one sees them, and then not, yet one knows that they are there. [...] our powers of thought grasp both the visible and the invisible.

7. Megalomania

In my paintings I showed objects located where we would never find them. [...] Given my desire to make everyday objects shriek out loud, they must be arranged in a new order and acquire a disturbing sense.

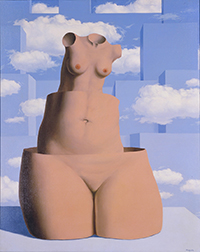

René Magritte. Megalomania (La Folie des grandeurs), 1962. The Menil Collection, Houston

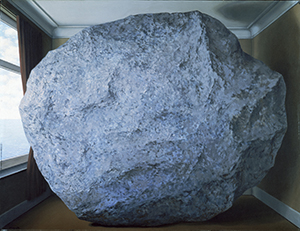

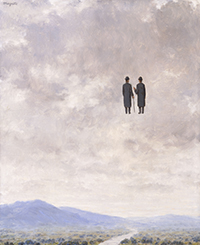

The opposing movement to mimicry, to an organism’s tendency to subject itself to its surroundings and dissolve into them, is megalomania, which tends to liberate a body or object from its context. With Magritte, megalomania became a change of scale through which he extracted an object or body from its habitual context and located it elsewhere. While with mimicry the body is devoured by the space, with megalomania it is the body that consumes the surrounding context.

The enlarged element in the artist’s works can be a natural object - an apple, a rock, a rose - and have a rounded shape, contrasting with the artificial, cubic space in which it is enclosed. Lewis Carroll, whom Magritte greatly admired and who was acknowledged by André Breton as a forerunner of Surrealism, was particularly expert at this device. The most evident source of inspiration that Magritte took from Carroll’s Alice is his series of paintings entitled La Folie des grandeurs. Their principal motif is a sculpted female torso divided into three hollow parts, each one fitted into the next like Russian dolls or like a telescope.

René Magritte. The Art of Conversation, 1963. Private collection

When megalomania manifests itself on the exterior it takes the form of ascent. Enlargement and levitation produce the same effect of removing the object or person from their context and projecting them into a new, neutral one where they are much more visible. Examples in Magritte include the bells that are blown up to a huge size and rise up like great balloons, planets or spaceships; the men in bowler hats conversing in the air; or the rock which becomes the principal motif in various late paintings.

In thinking that the stone must fall, the viewer has a greater feeling of what a stone is than he would if the stone were on the ground. The identity of stone becomes much more visible. Besides, if the rock were on the ground you wouldn’t notice the painting at all.

The essence of an object is revealed when we locate it in an unexpected situation, or even more, in a situation that is incompatible with its intrinsic nature.

RENÉ MAGRITTE. PHOTOGRAPHS AND FILMS

The Magritte machine is completed with an installation in the Museum’s first floor Balcony Gallery. It presents a selection of photographs and amateur films made by the artist himself. Magritte never considered himself a photographer but he was undoubtedly interested in film and photography in his daily life.

Rediscovered in the mid-1970s, these snapshots of his Surrealist friends, various self-portraits and photographs of the paintings that he was working on, as well as reels of film shot by the artist are presented in the exhibition in the manner of a family album. They include remarkable images filled with Magritte’s unique spirit.

René Magritte. Photographs and films is a selection of pieces from the exhibition The Revealing Image, curated by Xavier Canonne, director of the Musée de la Photographie in Charleroi. This display can be visited free of charge.

EXHIBITION DETAILS

- Title:

- The Magritte machine.

- Organisers:

- Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in collaboration with Fundación “la Caixa”.

- Sponsorship:

- Comunidad de Madrid.

- Venue and dates:

- Madrid, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 14 September 2021 to 30 January 2022. Barcelona, Caixaforum, 24 February to 5 June 2022.

- Curator:

- Guillermo Solana, artistic director of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

- Technical curator:

- Paula Luengo, responsible of the Exhibitions Department, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

- Number of works:

- 95

- Publications:

- Catalogue with essay by Guillermo Solana and biography