Käthe Kollwitz: Life, Death, and War

National Gallery of Ireland

6 September - 10 December 2017

6 September - 10 December 2017

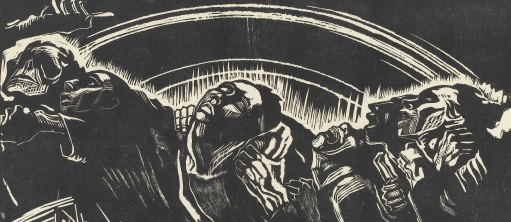

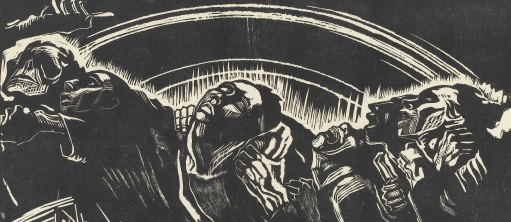

The Volunteers Plate 2 from the cycle War.

An exhibition of 40 prints and drawings by the German artist Käthe

Kollwitz (1867-1945) will be shown in the National

Gallery of Ireland. It is an opportunity for visitors to discover this

important artist who created almost 300 prints, around 20 sculptures and

some 1450 drawings during her long career.

The works in the exhibition, specially selected by the Gallery from the superb collection at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, will allow visitors to reflect on the effects of war, in particular the grief left in its wake.

Kollwitz’s five print cycles: Revolt of the Weavers (1893-98),

War (1921-22),

Proletariat (1924-25),

and Death (1934-37) place her among the foremost printmakers of the twentieth century.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a free illustrated brochure, and a programme of talks and music.

Curator: Anne Hodge, National Gallery of Ireland

Nice little review

The works in the exhibition, specially selected by the Gallery from the superb collection at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, will allow visitors to reflect on the effects of war, in particular the grief left in its wake.

Kollwitz’s five print cycles: Revolt of the Weavers (1893-98),

The Peasants’ War, 5: Outbreak, 1902/03 (1921 edition) (Soft-ground etching with line, drypoint, aquatint and stopping out on paper – courtesy of Staatsgalerie Stuttgart)

The Ploughman-1907Peasant War (1902-08),

War, 1: The Sacrifice, Spring 1922 (Woodcut on paper – courtesy of Staatsgalerie Stuttgart)

War (1921-22),

Proletariat (1924-25),

Death With a Girl in Her Lap Artist: Kathe Kollwitz

and Death (1934-37) place her among the foremost printmakers of the twentieth century.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a free illustrated brochure, and a programme of talks and music.

Curator: Anne Hodge, National Gallery of Ireland

Nice little review

Galerie St. Etienne

24 West 57th Street, New York NY 10019

October 26, 2017 - February 10, 2018

Käthe Kollwitz

Never Again War! 1924. Lithograph with text on dark tan poster paper. 37" x 27" (94 x 68.6 cm). Knesebeck 205/IIIb. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Poverty

1897. Lithograph on yellow chine collé, mounted on heavy white wove paper. Signed, lower right. 6 1/8" x 6 1/8" (15.4 x 15.4 cm). Plate 1 from the cycle Revolt of the Weavers. Printed prior to 1907, before the edition of 50 numbered impressions published in 1918. Knesebeck 33/AIIIa.

Storming the Gate

Before 1897. Wash and ink on heavy ivory wove paper Signed, center right. 23 1/4" x 17 1/2" (59.1 x 44.5 cm). Study for the etching of the same title (Knesebeck 37) from the cycle Revolt of the Weavers. Nagel/Timm 135. Private collection.

Storming the Gate

1983-97. Etching on ivory wove paper. Signed, lower right; signed by O. Felsing, and numbered 11/50, lower left. 9 3/8" x 11 5/8" (23.8 x 29.5 cm). Plate 5 from the cycle Revolt of the Weavers. From the edition of 50 numbered impressions published in 1918. Knesebeck 37/IIc.

Outbreak/Charge

1903. Etching on heavy wove paper. Signed, lower left. 20" x 23 3/8" (50.8 x 59.4 cm). Plate 5 from the cycle Peasant War. From the first edition of approximately 300 impressions published in 1908. Knesebeck 70/VIIIb. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Working Woman with Blue Shawl

1903. Lithograph in two colors on heavy cream wove paper. 13 7/8" x 9 3/4" (35.2 x 24.6 cm). Impression from the regular edition, with printed text in the lower margin. Knesebeck 75/AIIIb.

Woman with Scythe

1905. Etching on wove paper. Signed, also by O. Felsing, lower left. 11 3/4" x 11 3/4" (29.8 x 29.8 cm). Plate 3 from the sycle Peasant War. Proof before any edition. Knesebeck 88/V. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Battlefield

1907. Etching on heavy white wove paper. Signed, lower right. 16 1/8" x 19 7/8" (41 x 50.5 cm). Plate 6 from the cycle Peasant War. From the first edition of approximately 300 impressions published in 1908. Knesebeck 100/Xb.

Raped

1907-08. Etching on heavy wove paper. Signed, lower left. 12 1/8" x 20 3/4" (30.8 x 52.7 cm). Plate 2 from the cycle Peasant War. From the edition of approximately 300 impressions published in 1908. Knesbeck 101/Vb. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

The Prisoners

1908. Charocal on white Ingres paper. Signed, upper right. 18 1/4" x 23" (46.4 x 58.4 cm). Study for plate 7 from the cycle Peasant War (Knesebeck 102). Nagel/Timm 429. Private collection.

The Prisoners

1908. Etching on Japan paper. Signed, lower right, and by O. Felsing, lower left. 12 7/8" x 16 7/8" (32.7 x 42.9 cm). Plate 7 from the cycle Peasant War. Fromt the edtiion published by von der Becke in 1931-41. Knesebeck 102/IXa. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Unemployment

1909. Etching on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower right, and signed by O. Felsing, lower left. 15 5/8" x 20 3/4" (39.7 x 52.7 cm). Proof before the numbered edition published in 1918. Knesebeck 104/VIc.

Pregnant Woman

1910. Etching on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower right. 14 7/8" x 9 3/8" (37.7 x 23.6 cm). From the edition published in 1921. Knesebeck 111/V.

Working Woman (with Earring)

1910. Etching on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower right, and by O. Felsing, lower left. 13" x 9 7/8" (32.9 x 25.1 cm). Knesebeck 112/IVc.

Free Our Prisoners!

1919. Lithograph with text on heavy dark beige paper. 26 3/4" x 36 1/8" (67.9 x 91.8 cm). Knesebeck 139/II. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Killed in Action (First Version)

1919. Lithograph on smooth paper. Signed, lower right. 14 1/8" x 11 3/4" (35.9 x 29.8 cm). One of three recorded impressions. Knesebeck 144. Private collection.

Help Russia!

1921. Lithograph with text on tan poster paper. 26" x 18 3/4" (66 x 47.6 cm). Knesbeck 170/AII. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

The Volunteers

1921-22. Woodcut on heavy white Japan paper. Signed, lower right, and numbered 63/100, lower left. 13 3/4" x 19 1/2" (34.9 x 49.5 cm). Plate 2 from the cycle War. From the edition of 100 impressions on this paper. Knesebeck 173/IVb. Private collection.

The Widow I

1922-23. Woodcut on heavy cream wove paper. 14 5/8" x 8 7/8" (37.1 x 22.5 cm). Plate 4 from the cycle War. From the edition of 100 impressions printed on the cover of the "A" edition of the portfolio.

The Sacrifice

1922. Woodcut on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower right, and numbered "B 4/100," lower left. 14 5/8" x 15 7/8" (37.1 x 40.3 cm). Plate 1 from the cycle War. From the edition of 100 impressions on this paper. Knesebeck 179/IXc.

Hunger

1923. Woodcut on thick, soft, textured off-white paper. Signed, lower right. 8 3/4" x 9" (22 x 22.8 cm). One of approximately 20 impressions. Knesebeck 182/VI.

The Survivors

1923. Charcoal on gray wove paper. Signed, lower right. 19 3/8" x 25 1/2" (49.5 x 64.8 cm). Study for the lithograph of the same title (Knesebeck 197). Nagel/Timm 985. Private collection.

Poster Against Paragraph 218

1923. Lithograph with text on thin tan poster paper. 18 1/2" x 17 1/8" (47 x 43.5 cm). Knesebeck 198/II. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Germany's Children are Starving

1923. Lithograph on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, upper right. 16 3/4" x 11 3/8" (42.5 x 28.9 cm). Impression from the edition published by Richter. Knesbeck 202/AIVa2.

Fight Hunger/Buy Food Stamps" (Beggars)

1924. Lithograph with text on dark tan poster paper. 13 3/4" x 18" (34.9 x 45.7 cm). Knesbeck 206/AII. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Käthe Kollwitz

Unemployed 1925. Woodcut, worked over in India ink and white tempera, on heavy soft textured Japan paper. Signed, lower right, and inscribed "I.Z" (1st s[tate]), lower left. 14 1/8" x 11 3/4" (35.9 x 29.8 cm). Plate 1 from the cycle Proletariat. Unique proof. Knesebeck 215/I. Private collection.

Unemployed 1925. Woodcut, worked over in India ink and white tempera, on heavy soft textured Japan paper. Signed, lower right, and inscribed "I.Z" (1st s[tate]), lower left. 14 1/8" x 11 3/4" (35.9 x 29.8 cm). Plate 1 from the cycle Proletariat. Unique proof. Knesebeck 215/I. Private collection.

Käthe Kollwitz

Cottage Industry 1925. Lithograph with text on thin, tan poster paper. Signed, lower right. 27" x 17 3/4" (68.6 x 45.1 cm). Poster for the 1925 Deutsche Heimarbeit-Ausstellung. Knesebeck 217/BII. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection

Prisoners Listening to Music

1925. Lithograph on soft cream Japan paper. Signed, lower right. 13 1/8" x 12 5/8" (33.4 x 32 cm). From the edition published for members of the Kunstverein Kassel between 1925 adn 1927. Knesebeck 223/IIIa.

Municipal Shelter

1926. Lithograph on off-white wove paper. Signed, lower right. 16 1/2" x 22" (42 x 56 cm). From the edition published for members of the Kunstverein Leipzig in 1926. Knesebeck 226/b.

The Agitator

1926. Lithograph on white wove paper. 12 1/4" x 8 1/2" (31.1 x 21.6 cm). Knesebeck 230/d.

Fettered Man

1928. Lithograph on Velin paper. Signed, lower right, and numbered "N. 21," lower left. 11 1/4" x 7 5/8" (28.5 x 19.3 cm). From the edition of 32 impressions. Knesebeck 241. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

66. 1931. Lithograph on yellowish, heavy, soft wove paper. Signed, lower right. 14 1/2" x 10 1/8" (36.9 x 25.7 cm). Knesebeck 252/IIc. Daniel Stoll and Sibylle von Heydebrand Collection.

Tower of Mothers

1937-38. Bronze with brown patina. 11 1/8" x 10 1/2" (28.3 x 26.7 cm). Cast in 1941 by H. Noack, Berlin, at the artist's request. Private collection.

68. Seed-Corn Must Not be Ground

1941. Lithograph on smooth ivory wove paper. Signed, lower right. 14 1/2" x 15 1/2" (37 x 39.5 cm). Very rare proof; no edition was published. Knesebeck 274. Private collection.