January 14 to March 18, 2018

An exhibition featuring the works of the artist credited with inspiring the Art Nouveau movement opened Sunday, January 14, at The Hyde Collection.

Alphonse Mucha: Master of Art Nouveau includes more than seventy works drawn from the Dhawan Collection of Los Angeles, California, one of the most significant private collections of Mucha’s work in the United States.

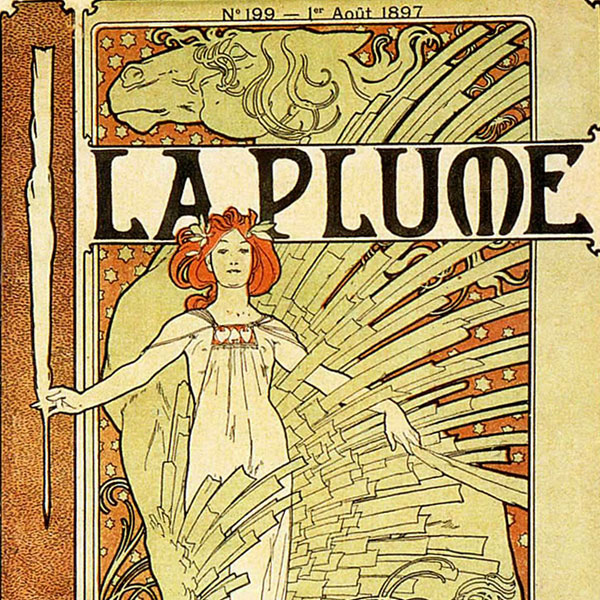

L'Estampe Moderne 1897

The exhibition examines how Mucha’s work helped shape the aesthetics of French Art Nouveau at the turn of the century. Art Nouveau, or New Art, describes a style in architecture, and visual and decorative arts that flourished from the 1890s through 1910. It emphasized the beauty of natural forms in everyday life. Art Nouveau featured a sinuous or “whiplash” line, flattened space, and botanical shapes and patterns.

“Mucha’s early work is centered on the epitome of beauty,” said Jonathan Canning, director of curatorial affairs and programming at The Hyde Collection. “With use of subtle color schemes, lavish scrolling text, and exquisite women, he defined the Art Nouveau movement.”

Many of the works in the exhibition feature beautiful women, dramatic curving lines, flowers, and plants. Mucha worked across many media and those are revealed in the exhibition, which includes lithographs, drawings, paintings, books, and advertisements. Highlights include four versions of a poster Mucha created for actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1894 — an assignment largely believed to have launched Mucha’s prolific career —

and two posters advertising Job cigarette papers from 1896 and 1898.

The Slavs in their Original Homeland , Oil and tempera on canvas

"The Celebration of Svantovit"More images

Mucha (July 24, 1860-July 14, 1939), the most successful decorative graphic artist of his day, considered his life’s masterpiece to be Slav Epic, twenty large-scale paintings depicting the history of the Czech lands and people. The latter part of Mucha’s career is also included in the exhibition, with samples of his work after returning to his homeland in the early part of the twentieth century, including bank notes and one of the Slav Epic panels.

New York Times article about the Slav Epic

“Later in his career, Mucha wanted to separate himself from his commercial art, and instead devoted himself to making art that celebrated the history of his people,” Canning said. “He was inspired by the traditional dress, the folklore, and landscapes, and proud of the Czech culture.”

About Alphonse Mucha

Alphonse Maria Mucha was born in Ivančice, a rural town in Moravia

(now part of the Czech Republic) at the height of the Czech National

Revival. He grew up with a strong belief in national heritage and an

independent Czech nation. Those beliefs would shape his artwork in the

latter part of his career.Musical ability earned young Mucha a scholarship to the Gymnázium Slovanské secondary school in Brno. Poor academic performance led to his being asked to leave. He vowed to earn a living as an artist and applied to Prague Academy of Art, but was rejected. Undeterred, he worked as a court clerk while designing sets for local theaters and magazines. He signed on as an apprentice scenery painter at a theater in Vienna, where he took art classes.

Mucha was commissioned to paint murals for wealthy landowners, one of whom became his benefactor and paid for formal art training at Munich’s Academy of Art. By the 1880s, he regularly contributed artwork to magazines. Moving to Paris in 1887, he enrolled in Académie Julian, then Académie Colarossi, both of which encouraged students to meld art and design.

His sponsorship ended, Mucha left art school and worked as an illustrator for magazines and, ultimately, books. His artwork developed a following and was regularly exhibited. He taught drawing out of his studio, classes that became known as Cours Mucha. They were eventually so successful that the artist was asked to teach at the Académie Colarossi and ran a drawing course at James McNeill Whistler’s Académie Carmen.

But his catapult to fame is reported to have happened quite by accident. The young commercial artist was in a print shop in 1894 when iconic French actress Sarah Bernhardt called needing a poster for one of her upcoming shows. The result is the poster Gismonda. Ms. Bernhardt was so moved by Mucha’s work, she signed him on for a six-year contract, during which he created advertisements so beautiful, art lovers searched them out throughout the city, removed them from their posts, and brought them home to hang on their parlor walls.

In the years that followed, posters became an art in their own right, and Art Nouveau flourished. Mucha moved into a new studio, where he was introduced to pastels and sculpture. His works were commissioned by Imprimerie Champenois, one of the most important printers of the period, Job cigarette paper, and other companies seeking advertisements. In 1895, Mucha teamed up with jeweler Georges Fouquet and the pair redefined jewelry design, making aesthetic more important than the monetary value of the materials used.

When Fouquet decided to move his jewelry boutique to the luxurious Rue Royale in Paris, he called on Mucha to design all aspects of his shop — exterior, interior, furniture, light fittings, and showcases. Mucha conceived the shop as a complete work of art inspired by the natural world.

After the turn of the century, Mucha traveled to the United States several times to secure funding for Slav Epic. He painted portraits, taught classes, and befriended President Theodore Roosevelt.

He ultimately secured funding for the project from Chicago industrialist Charles Richard Crane, heir to R.T. Crane Brass and Bell Foundry. In 1910, he returned to Bohemia and spent the next two decades working on the twenty-panel series. Some of the completed panels were exhibited in the United States, attracting massive crowds to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brooklyn Museum in 1920-21.

Mucha focused on social and cultural projects for the new Czechoslovakia, including stamps, bank notes, murals, and cultural projects until his death in 1939.

Complete illustrated checklist