Clark Art Institute

November 10, 2018–February 3, 2019

Currier & Ives (American, 1834–1907) after Artist Unknown (American, 19th Century), The Great Fire at Boston, Nov. 9 & 10, 1872, 1872. Hand-colored lithograph on paper, 7 15/16 x 12 11/16 in. Clark Art Institute, Gift of J. Thomas Wilson, 1981.23

Natural Disaster

The public’s interest in nature’s unrelenting fury developed into a morbid fascination with disaster in the nineteenth century. Popular magazines and scientific journals transformed floods, fires, and catastrophes at sea into cataclysmic spectacles.

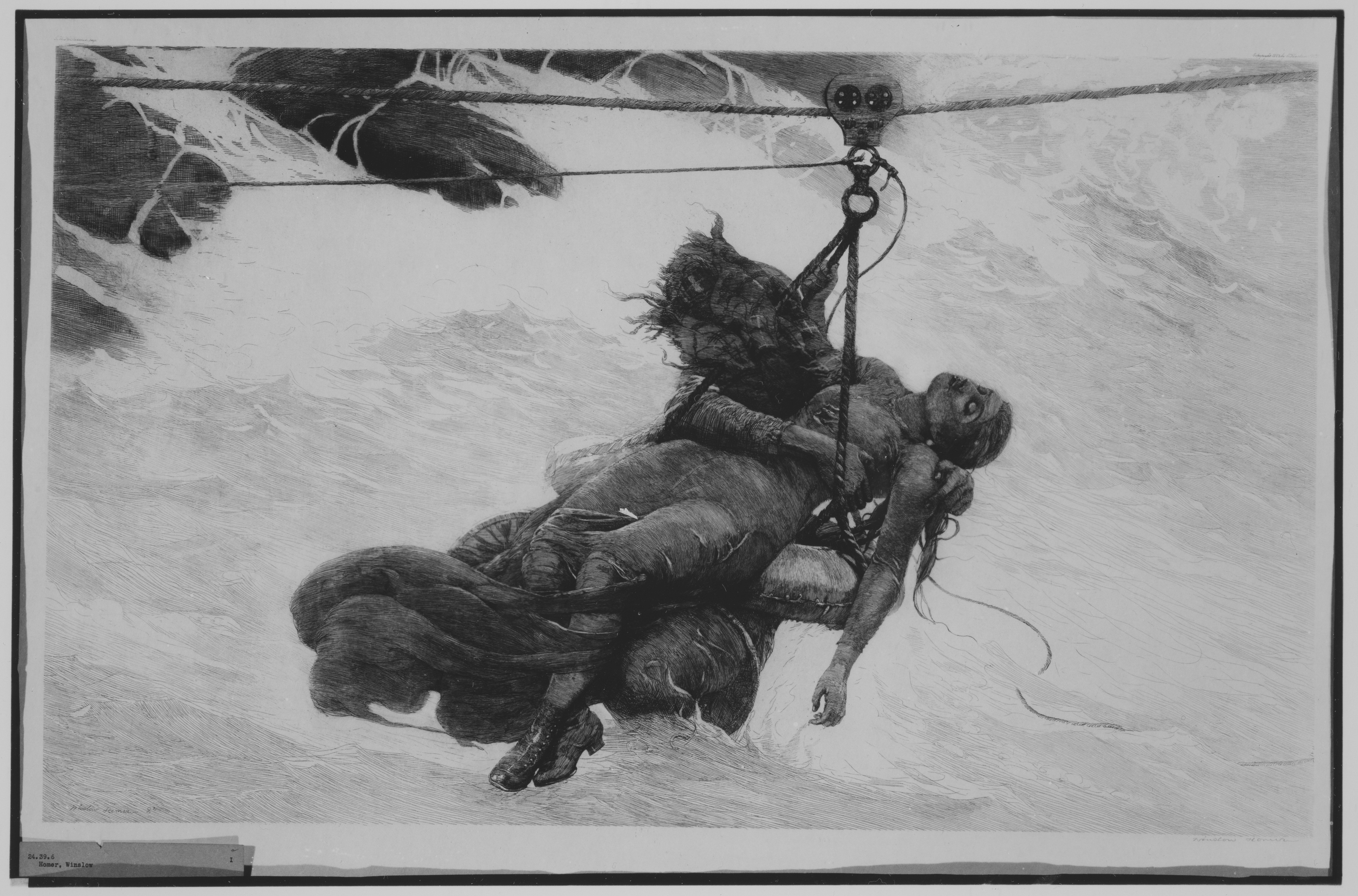

Currier & Ives issued lithographs like The Great Fire at Boston, Nov. 9 & 10, 1872 (1872) to document the devastating blazes that engulfed the city, while Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910) contemplated water’s unbridled power in etchings such as

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910), Saved, 1889. Etching on paper, 16 7/8 x 30 1/16 in. Clark Art Institute, 1972.16

Saved (1889), portraying a rescue in choppy waters.

The eight eruptions of Mount Vesuvius in the nineteenth century formulated the basis of a popular fireworks show staged in New York that purported to reenact the decimation of Pompeii.

Charles Graham’s (American, 1852–1911) Fire-Works at Manhattan Beach—“The Last Days of Pompeii” (1885) transforms the prospect of disaster into an eerily beautiful and exciting occurrence.

Alluring Landscapes

Mountainous topographies, rocky bluffs, and plummeting waterfalls by artists such as Aaron Draper Shattuck (American, 1832–1928) illustrate how the modern foundation of geology and other natural sciences influenced artistic portrayals of the landscape.

The replication of nature’s minutest details in Shattuck’s Monument Mountain (c. 1862) in southern Berkshire County, Massachusetts,

in William Westall’s (English, 1781–1850) Entrance to Peak Cavern, Derbyshire (c. 1822),

and in a late 1890s color photochrom of Niagara Falls elicited wonder and excitement among viewers who might imagine the exhilarating experience of encountering these geographic phenomena.

William Bradford’s (American, 1823–1892) photographs of towering arctic icebergs and

Timothy O’Sullivan’s (American, c. 1840–1882) Cañon de Chelle, Walls of the Grand Cañon about 1200 feet in height (1871) brought these locales into the popular mindset while also scientifically documenting geological features using the latest in photographic technology.

Volatile Atmospheres

The late-eighteenth-century invention of the hot air balloon contributed to modern meteorology. By the end of the century, new discoveries in weather encouraged an interest broader than the bounds of the atmosphere—one that questioned the stars, considered the moon’s formation, and examined the power of the sun. Scientists’ observations from the air, as well as increasing global travel, brought heightened awareness of atmospheric conditions. Publications like early meteorologist Luke Howard’s 1803 classification of clouds as cumulus, stratus, and cirrus inspired artists such as Joseph Mallord William Turner (English, 1775–1851) and John Martin (English, 1789–1854) to portray weather’s volatility with greater attention to detail.

]William Baillie’s (Irish, 1723–1818) dramatic The Three Trees (c. 1800) depicts a zigzagging lightning bolt as it strikes three trees on a hilltop. Based on Rembrandt van Rijn’s (Dutch, 1606–1669) etched landscape of the same name, Baillie’s etching added darkened storm clouds and violent lightning, suggesting an interest in the relationship between electricity and this severe form of weather.

Extremes Imagined

Extreme Nature! is drawn primarily from the Clark’s permanent and library collections with additional material on loan from The Troob Family Foundation, Williams College Museum of Art, and Williams College’s Chapin Library. The exhibition is on view in the Eugene V. Thaw Gallery for Works on Paper.