Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

25 October 2018 to 27 January

2019

CaixaForum’s exhibition space in Barcelona,

21 February to 26 May 2019.

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza is presenting

Beckmann. Exile figures, the first exhibition in Spain in twenty years to be

devoted to the a rtist, one of the most important of the 20 th century.

While

close to New Objectivity at the outset o f his career, Max Beckmann (Leipzig, 1884

– New York, 1950) created a unique and independent ty pe of painting, realist

in style but filled with symbolic resonances, which came to constitut e a

vigorous account of society of his day. Following its display at the Museo

Thyssen, where i t is sponsored by the Comunidad de Madrid, it will travel to

CaixaForum’s exhibition space in Barcelona, from 21 February to 26 May 2019.

Curated

by Tomàs Llorens the exhibition will feature a total of 52 works, principally

paintings but also sculptures and lithographs, loaned from museums and collections

worldwide and including some of the artist’s most important creations, such as

The

Boat (1926),

Paris Society, 1931. Solomon R. Guggenheim

Museum, New York /

Society, Paris (1931),

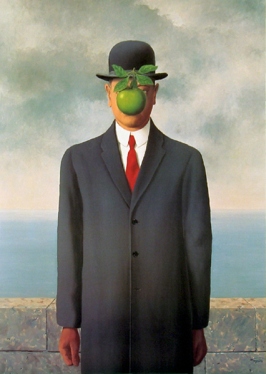

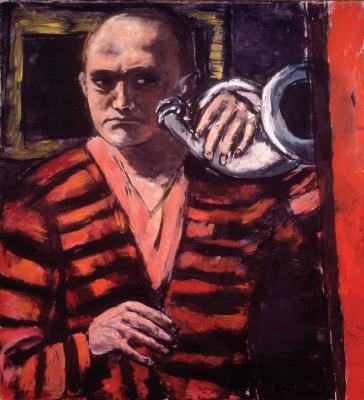

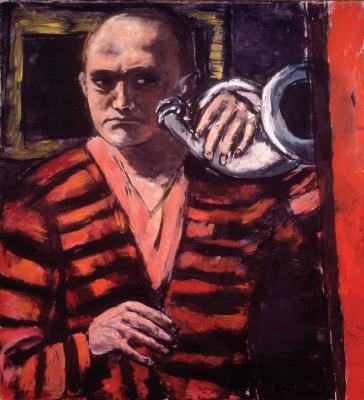

Self-Portrait with Horn , 1938. Neue Galerie, New

York, and private collection /

Self- portrait with Horn (1938),

City. Night

in the City (1950),

Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May

and The Argonauts (1949-50), the triptych that Beckmann

finished on the day he died at a relatively early age in New York.

The

exhibition is structured into two sections. The first, smaller one is devoted

to the artist’s time in Germany from the years prior to World War I when he began

to achieve public recognition, to the rise of Nazism in 1933 when Beckmann was

stripped of his post at the Frankfurt art school and was banned from exhibiting

in public. Works displayed in this section have been chosen for their

significance and importance within the artist’s oeuv e.

In the second, larger

section, which spans the years in Amsterdam (1937-47) and the United States

(1947-50) where he settled after he was obliged to leave Germany, the works

have been selected using a thematic criterion: exile, both in its literal sense

with regard to Beckmann’s own life, and figurative, in reference to the significance

it had for the artist as the basic condition of human existence in general.

As a result, his allegorical paintings

– to which he devoted most time and effort (all his triptychs and large-format canvases

are allegorical compositions) – are the most extensively represented in the exhibition.

The portraits, landscapes and still lifes, traditional genres in which Beckmann

worked throughout his career, have also been chosen for their allegorical

resonances.

This part of the exhibition is structured around four metaphors

relating to exile:

Masks , which focuses on the loss of identity associated

with the circumstances of exile;

Electric Babylon , on the vertiginous modern city

as the capital of exile;

The long goodbye , which looks at the parallel between

exile and death; and

The Sea , a metaphor of the infinite, its seduction and alienation.

A German painter in a bewildering Germany

The conviction that German art had

its own character, different to that of France or Italy, was profoundly rooted

in the artists of Beckmann’s generation whose sensibility was oriented towards

the “emotion of life” rather than ideal beauty. This trait, repressed and

inexplicit for centuries, started to re-emerge during the modern era in parallel

to Germany’s new social and economic rise. With defeat in World War I, however,

the new confidence and self-esteem disappeared and was replaced by an acute

awareness of crisis while in the field of art naturalism was replaced by

Expressionism. Beckmann’s early painting is eclectic in style.

In addition to

Max Liebermann and Lovis Corinth, his work of this period recalls other German

artists of the previous generation. The most important long-lasting influence,

however, was that of Cézanne and Beckmann’s concern to combine the representation

of volume s with the two-dimensional surface of the canvas would be one of his

principal obsessions throughout his career.

Beckmann believed that there was no

such things as a new painting based on new theoretical principles: for him, the

different personalities of artists represented the only new element in art.

His interest in allaying himself with the great tradition of European painting became

the principal aim of his work during his initial period, leading him to challenge

the avant-garde of the Expressionist painters of his day. His profound rejection of the collective, sectarian and doctrinal aspect of these mov ements provided

the basis of his individualist position agai nst all the collective art trends

that he encountered during the course of his life.

Max Beckmann: Abtransport der Sphinxe, [Transporting the Sphinxes], 1945

Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe ⓒ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015

“The great orchestra of mankind lies in the city” During the early

years of his career Beckmann devised a new type of painting that was realist

and “of the moment”. It brought him initial success and began to be recognised

in art circles of the day. He would become fully established with his first monographic

exhibition in 1913. That same year he introduced a new theme into his painting:

street scenes of Berlin that evoke the metropolitan character of the big city.

While already adopted by the Futurists and Expressionists, Beckmann’s focus on this

subject was notably different, offering an objective vision through the gaze of

the painter as fas cinated witness to its agitation. The following years were

marked by the experience of t he war. Like many German artists of his generation

Beckmann enlisted as a volunteer, not out of patr iotism but in search of a life-

changing experience, which would ultimately become a form of artistic learning.

Following temporary leave of absence from the army due to a nerv ous breakdown,

in 1915 he moved to Frankfurt where he lived until 1933. This was the start of

a new life, both in personal terms with the crisis of his first marriage and

his second in 1925 to Mathilde von Kaulbach (known as “Quappi”), and in

artistic ones.

Beckmann’s reputation c ontinued to grow. “I believe that I love

painting as much as I do precise ly because it forces me to be objective. There

is nothing I hate more than sentimentality” the artist wrote in 1918 in a text

that sets out his creative principles. Rejection of sentimentality, obje ctivity,

concentration on the volumetric aspect of the painting: Be ckmann was the first

artist to formulate these basic princip les, using them to establish one of the

prevailing trends in the post-wa r aesthetic. Nonetheless, when this aesthetic

became a fashionable tend ency with the name of Neue Sachlichkeit [New

Objectivity], of which he was considered by many to be the principal representative, Beckmann continued to reject being labelled in any way. During the years of

the rise of Nazism Beckmann’s positi on became increasingly difficult. He was a

prominent pub lic figure in Frankfurt and while his painting revealed its

German roots and was only moderately modern, his contacts with the Jewish soci al

elite told against him.

He returned to Berlin in 1933 in search of greater anonymity.

German museums were, however, ceasing to display his work and hi s income

started to decline.

On the day of the inauguration of the Degenerate Art exhibition

in 1937 Beckmann caught a train to Amsterdam and never returned to Germany. Following

a chronological order, this first part of this exhibition aims to present all

the different aspects of Beckmann’s output during the period in question up to

his exile.

Among the most important works shown in this section, alongside

various sculptures and prints are:

The Street Family Picture , 1920. The Museum

of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller

Carnival , Double

Portrait , 1925. Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf 4 (1914),

Self-portrait with a

Glass of Champagne (1919),

Self-portrait as a Clown (1921),

Double Portrait.

Carnival (1925),

The Boat (1926),

Carnival in Paris (1930)

and Society, Paris (1931).

Leaving and beginning

“What I want to show in my work is the idea that is

hidden behind what we call reality [...] From the starting point of the present

I look for the bridge that leads from the visible to the invisible [...]” The most

important innovation in Beckmann’s Berlin phase, between 1933 and 1937, was the

appearance in his work of a new pictorial format, namely the triptych. Adopted by

other German painters during the interwar period, for Beckmann it represented a

conscious reference to medieval German art, connecting 20 th -century German

painting with its Gothic and Renaissance past. As a type of painting intended for

public consumption the triptych would gradually replace the large-format 19 th -century

salon painting while with Beckmann it is also associated with the large-format

paintings of his youth. These works reflect a radical rethinking not just

regarding his creative output but also his relationship with the world and his

concept of t he meaning of life and man’s fate. Investigating the visible and the

most sensory aspect of the world in order to capture the invisible is

characteristic of allegory. The principal effect that exile had on Beckmann’s

work was to increase his commitment to this type of painting, princ ipally expressed

in the form of triptychs.

The exhibition includes three of the ten that he produced

(one of them unfinished), including The Beginning, which he started in

Amsterdam in 1946 and completed in the United States in 1949. In it, the artist

represented his new beginnings while evoking childhood memories. Masks The

first effect of exile is to question the natural identity of the exiled

person. Any individual expelled from their home has also been deprived of the ir

identity to some extent. The paradigm of this condition is the wandering artist,

circus or cabaret performer who appears before the audience in a mask or costume.

Another such paradigm is carnival.

Among the principal works in this section

are:

Self-portrait with Horn (1938), one of two self-portraits that Beckmann

painted in his early months in Amsterdam and among his most memorable works;

the triptych Carnival (1943), in which the artist includes himself as Pierrot

dressed in white in the central panel; Begin the Beguine (1946), in which the

festive atmosphere of the dance is counterbalanced by a setting that suggests a

latent menace; and

Masquerade (1948), which reveals the same combination of the

Begin the Beguine , 1946. Collection of the University of Michigan Museum of

Art, Ann Arbor. Museum Purchase, 1948

The Beginning , 1946 - 1949. The Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot ( 1876–1967

), 1967 5

festive and the sinister and in which, as in so many of Beck mann’s

works, the couple in fancy dress are the artist and his second wife Quappi.

Among these paintings, those dating from the artist’s relatively happy years in

the United States re veal how the allegorical knot that connects exile with disguise

and with the most sinister side of the crisis of identity continued to be present

in Beckmann’s consciousness.

Electric Babylon

The large city is the

paradigmatic place of modern man’s loss of identity. In historical terms this sentiment

first emerged around the end of the 19th and start of the 20th centuries but

there are ancient precedents.

The Bible recounts the Jews’ exile to Babylon, a

place where the divine sense of belonging that constituted their identity as a people

was erased as they were subjected to a multitude of false idols. “Electric Babylon”,

the title for this section, thus refers to the modern metropolis where the

frontiers between the rural a nd the urban, the natural and the artificial and

between day and night break down. The result is a labyrinth of bars, gambling halls,

dance halls and performance, spaces of temptation and pe dition that present

themselves to the biblical Prodigal Son. The city as modern metropolis, “where everyone

is a unique event” in Beckmann’s words, became one of the key themes of German

sociology at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The transition from the

countryside to the city is the quintessence of modernity and the experience of

that modernisation, which traumatically culminated in World War I and the

destruct ion of hope, would profoundly influence Beckmann’s work. For him, the metropolis

presented itself as a performance and among its different forms he was most

attracted to the circus and the variety show.

Large Variety Show with Magician

and Dancer

Large Variety Show with Magician

and Dancer (1942) is the most spectacular of his interpretations of this theme:

here everything is slight-of hand, confusion, fireworks, smoke and the glitter of

sequins. Babylon, city of exile, is also ho wever the capital of temptations, the

paradigmatic site of the perdition of

The Prodigal Son

The Prodigal Son (1949), another of the

artist’s essential works on display in this section and a subject to which he had

devoted a series of watercolours in 1918. This section also includes a number

of watercolours dating from Beckmann’s final years when he had fulfilled his

dream of moving to New York and enjoye d a prolific and highly successful phase.

Plaza

(Hotel Lobby) ,

Plaza

(Hotel Lobby) , 1950. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York.

Estate of Max Beckmann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Germany

Plaza (Hotel Vestibule)

and

and Night in the City , both of 1950 are the

direct result of his everyday life in the great metropolis, the greatest “orchestra

of humanity on the face of the earth” in the artist’s own words. The long

goodbye To leave is to die a little, or a lot. With every le ave-taking

something breaks. The exile is a figure of death and vice versa. Furthermore,

while Beckmann was an artist who persistently questioned his German identity

from the start of his career, in the new Germany that emerged with the rise of

National Socialism the parallel between exile and death became a reality.

Having settled in Amsterdam after they left Germany,

Max and Quappi lived in the anonymity of exile and with an uncertain future. This

was once again the start of a new life. The artist’s first large-scale

allegorical composition that he began in Amsterdam is entitled

Birth (

Birth (1937). A few

months later he painted

Death

Death (1938). With a horizontal format and marked

compositional and iconographic parallels, they seem to be devised as a pair although

Beckmann sold them separately.

Birth and

Death are the two great portals of our

existence, the obverse and reverse of a single reality and the same image of

the exile. We are born itinerant artists, unaware of what life holds for us. We

die as travellers, again not knowing how our end will be. What lies between is

pure exil and primarily suffering. Life is torment and no one can escape the

force of destiny. The pr incipal force that drives us during that long goodbye

of life is desire, of which the most explicit manifestation is sexual desire. Together

with the above-mentioned

Death ,

Vampire

Vampire (1947-48),

Large Still Life with

Sculpture and Air Balloon with Windmill (1947) are some of the works to be seen

in this secti on.

The sea

The sea is one of the principal motifs in Beckmann’s work

, an image of travel and exile, an immense extension in which nothing is still

and a medium in which, like rivers, human exist ence flows to its end, is

purified and renews itself. Pure fate and pure menace: a seductive glitter for

the Argonauts and a doomed blackness for Icarus. Seduction and threat.

Transporting

the Sphinxes

Transporting

the Sphinxes (1945), one of Beckmann’s most enigmatic works;

Cabins

Cabins (1948), in which

a boat becomes the representation of a city in miniature;

and

Falling Man (1950),

one of his most surprising paintings, are among the most important works in

this section.

The exhibition culminates and concludes with the triptych

The

Argonauts. Beckmann worked on it for more than a year and a half and

considered it completed on 27 December 1950, dying of a heart attack later the

same day. He produced the left panel first, which he referred to as “the

painter and his model” as an independent work, subsequently completing it with

two further canvases and at this point referred to the whole as “the artists”.

The left panel thus became an allegory of painting, the right of music and the

centre of poetry. However, according to Quappi, having had a dream about the

Greek legend, a few days before he finished the painting he started to use the

title of The Argonauts and at this point he may have added various classical

attributes such as the s word held by the artist’s model and the sandals. The

Argonauts completes a cycle begun 45 years before with Young Men by the Sea , which

marked the triumphal start of the painter’s career and which also has the sea as

its backdrop.

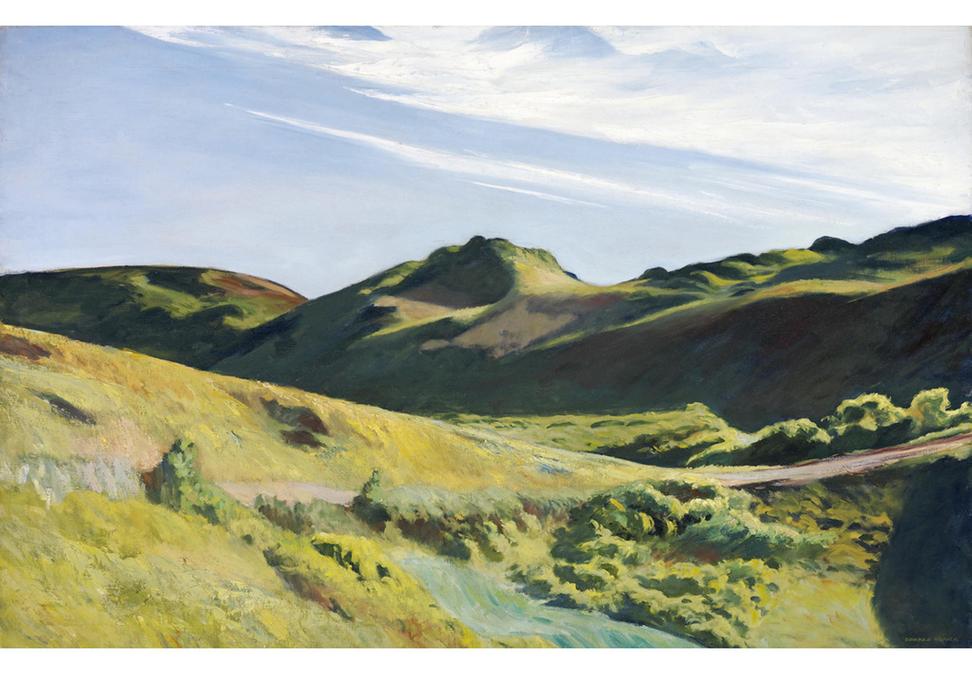

Oil on canvas, 65.1 × 100.9 cm

New York, The Museum of Modern Art