ALBERTINA Museum

21

September 2018–6 January 2019

This autumn,

the ALBERTINA Museum is mounting Austria’s first broad-based presentation of

works by Claude Monet (1840–1926) in over 20 years.The 100 paintings to be

shown include important loan works from over 40 international museums and

private collections such as the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Museum of Fine Arts

Boston, the National Gallery London, the National Museum of Western Art in

Tokyo,and the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

This retrospective

presentation, realized with generous support from the Musée Marmottan Monet in

Paris, illuminates Monet’s development from realism to impressionism and onward

to a mode of painting in which colors and light gradually separate from the

subjects that reflect them, with the motif as such breaking free from the mere

observation of nature.As a consequence, the artist’s late works would come to

pave the way for abstract expressionism in painting.

Monet, the “Master of Light”

“A panorama of water and water lilies, of light and sky,” the collector René Gimpel noted in his diary on August 19, 1910 after paying a visit together with the art dealer Georges Bernheim to Claude Monet in Giverny, where he saw “a dozen canvases placed one after another in a circle on the ground, all about six feet wide by four feet high.”

This rencontre with Claude Monet took place in a high-ceilinged studio filled with light and air, which the painter had built on his property in Giverny to work on his ideas for the so-called Grandes Décorations, which he later donated to the French state. What Gimpel saw were smaller, easily movable canvases, which were preliminary works for this endeavor. Monet, who originally planned a circular installation of his water lily pond paintings in the Hotel Biron in Paris,had arranged them accordingly. His plan was abandoned after 1920, however, in favor of a realization in two oval rooms of the Orangerie.

The painting from the Batliner Collection in the ALBERTINA Museum, The Water-Lily Pond, is one of these preparatory works, some of which were sold during Monet’s lifetime.

After the death of Michel Monet, the son and sole heirof Claude Monet, the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris acquired the Impressionist’s estate.Nearly ninety paintings, many of which Claude Monet had guarded with utmost care, were to find a new home—as Michel Monet stipulated in his last will—“in the Musée Marmottan [as] the largest and most beautiful Monet collection.”

It is therefore fortunate that the ALBERTINA Museum has found a partner in the Musée Marmottan Monet, which has provided forty of its most splendid paintings by Monet for this exhibition. For a short time, the ALBERTINA Museum’s Water-Lily Pond finds itself in the midst of those paintings, in the context of which it was created at the time.

With two other works from the Batliner Collection, which Monet painted inVétheuil and Giverny, as well as over fifty paintings on loan from about forty international institutions and works from private collections, the exhibition traces the life and work of Claude Monet with paintings that are both lavish and colorful, and yet at times also astonishingly chromatically reserved.

Precious international loans

The motif for this exhibition’s poster is the monumental work On the Boat, which Monet painted on the water in 1887; it is being shown courtesy of the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

As with the nature in Monet’s landscapes, this street is a place of constant activity that changes according to the time of day, the atmosphere, and the weather.

Among the impressive loan works, many of which are in large formats, there is also the Grainstack in Sunlight (1891, on loan from Kunsthaus Zürich), which Kandinsky saw in an exhibition on French impressionism and greatly admired. Despite his enthusiasm, however, Kandinsky had difficulty recognizing the motif—an effect that presaged Monet’s emancipation of colors and the advent of abstract painting.

Further highlights are Monet’s early winter paintings, including the portrait The Red Kerchief (1873, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA); two paintings of Rouen Cathedral from an extensive series that he created before this Gothic national monument that would themselves become icons of impressionism; and several paintings of the river Creuse in the Massif Central region done in very nasty weather that are pioneering in terms of their composition and use of color.

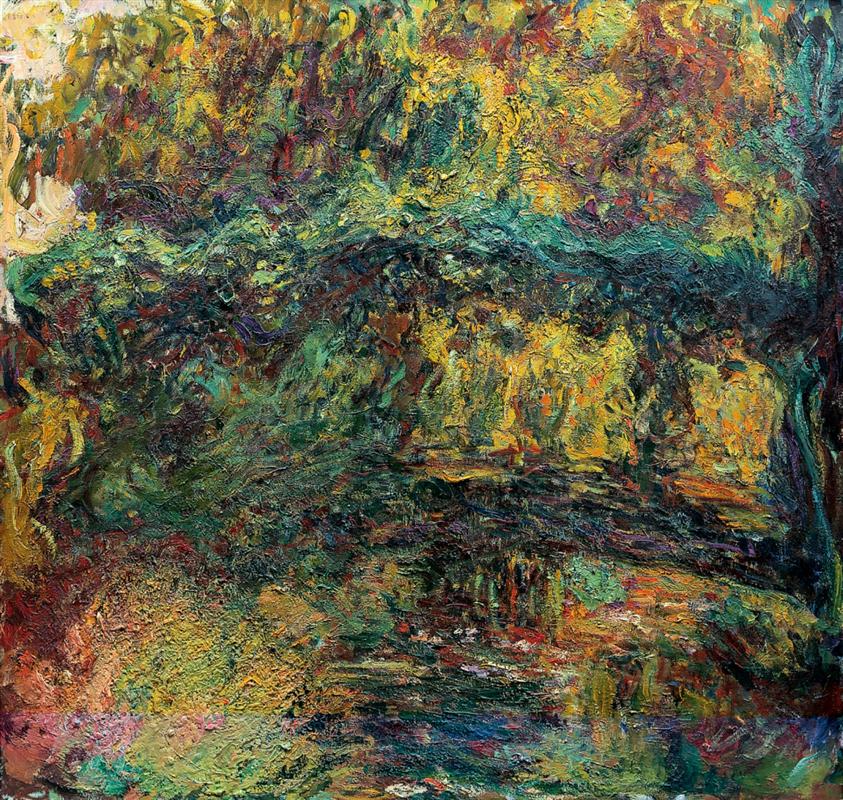

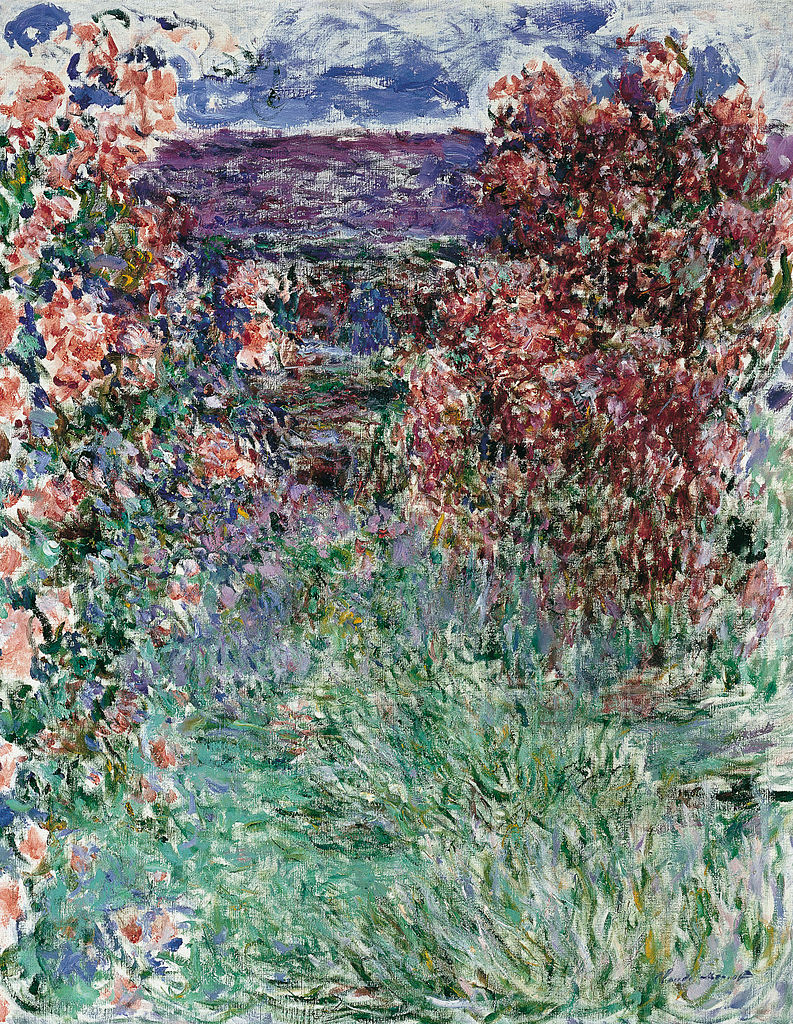

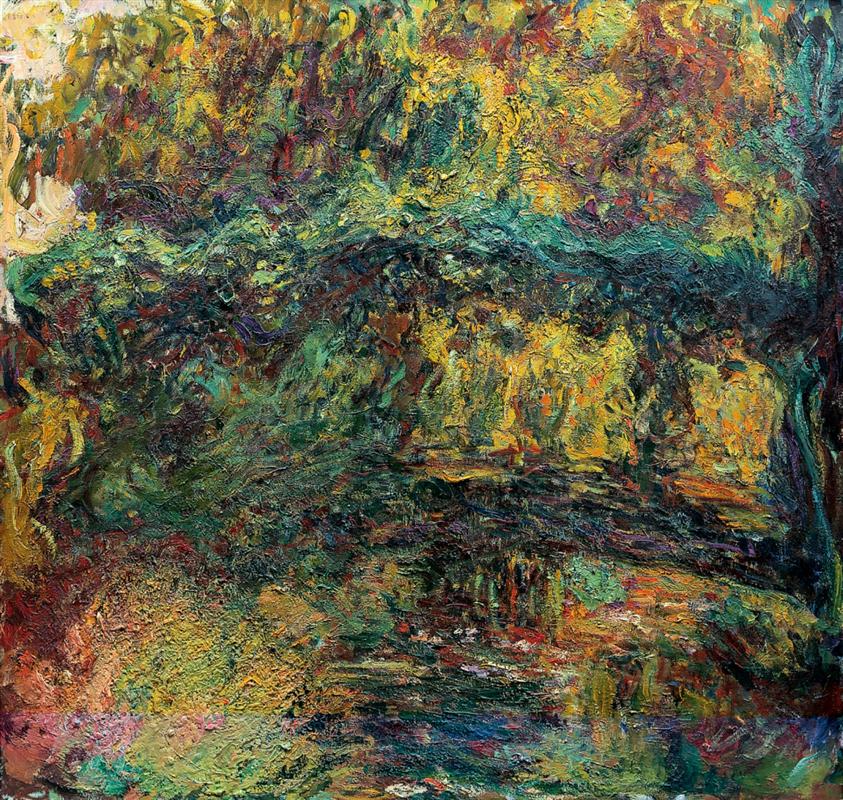

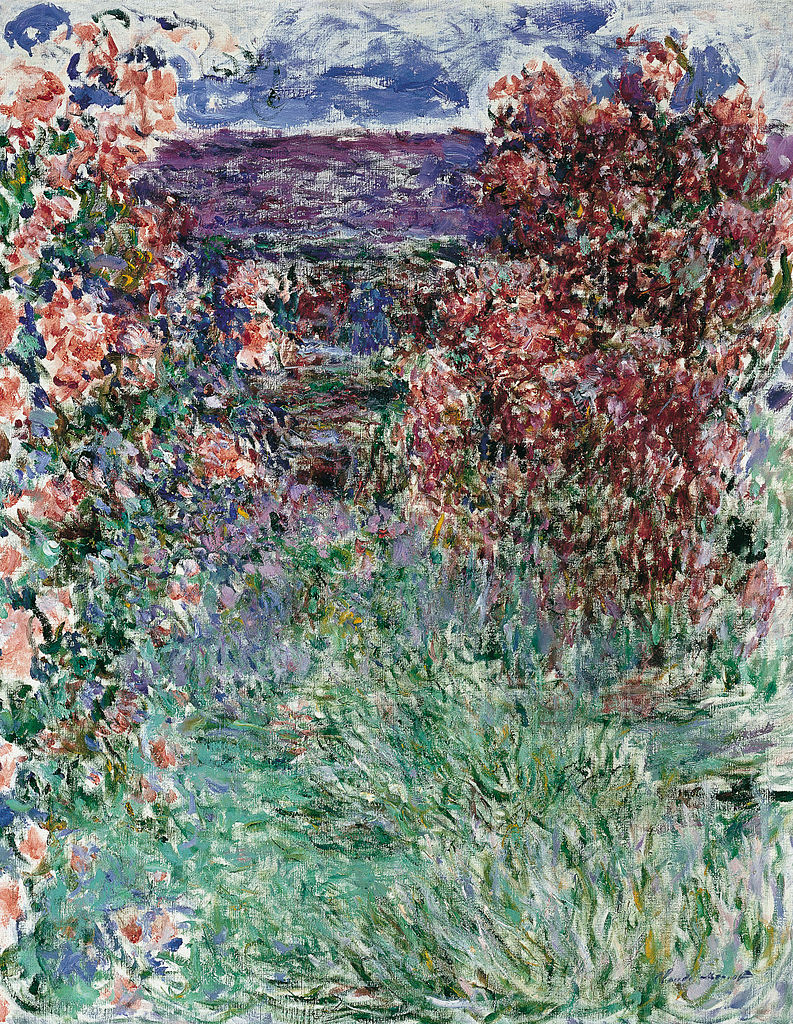

And from near the end of Monet’s life, by which point his eyesight was severely impaired and he limited himself to working in his garden at Giverny, this exhibition presents

The Japanese Bridge (1918–1924)

and his The House Among the Roses.

Water as a source of inspiration“A Floating World” is the evocative subtitle of the exhibition in the ALBERTINA Museum, the artist’s first large-scale retrospective in Vienna in more than twenty years. The Seine was a home to the pleinairist—both in terms of his various residences and his studio boat, from which he sought to capture the nature and life of the river and its shores with his paintbrush, regardless of the weather conditions.

Guided by one hundred paintings, the exhibition visitor follows in the footsteps of the most important Impressionist along the Seine, pausing at various stations of his life: in Paris, where Monet captured the pulse of modern life with flickering light; in Argenteuil, where he reconciled nature and technology; in Vétheuil, where, in the face of his precarious financial and family situation, he withdrew into solitude to devote himself to unspoiled and original nature; and finally in Giverny, where he arrived at a new aesthetic concept that led Impressionism out of its crisis and paved the way for modern painting.

The river also stands for the many aspects that characterize Monet’s oeuvre: the flowing world of the Japanese woodblock prints that influenced Monet; the coalescing of water, mist, fog, snow, and ice; the colors that change with the weather and lighting conditions; the reflections on the water surface.

The visitor also accompanies Monet to the coasts of Normandy and Brittany, to London and Norway, either to understand his beginnings in Le Havre and his repeated visits to the Atlantic coast, or to visit places together with the artist which promised him new inspiration for his painting.

Monet, the “Master of Light”

“A panorama of water and water lilies, of light and sky,” the collector René Gimpel noted in his diary on August 19, 1910 after paying a visit together with the art dealer Georges Bernheim to Claude Monet in Giverny, where he saw “a dozen canvases placed one after another in a circle on the ground, all about six feet wide by four feet high.”

This rencontre with Claude Monet took place in a high-ceilinged studio filled with light and air, which the painter had built on his property in Giverny to work on his ideas for the so-called Grandes Décorations, which he later donated to the French state. What Gimpel saw were smaller, easily movable canvases, which were preliminary works for this endeavor. Monet, who originally planned a circular installation of his water lily pond paintings in the Hotel Biron in Paris,had arranged them accordingly. His plan was abandoned after 1920, however, in favor of a realization in two oval rooms of the Orangerie.

Claude Monet | The Water Lily Pond, 1917-1919 | © The Albertina Museum, Vienna. The Batliner Collection

The painting from the Batliner Collection in the ALBERTINA Museum, The Water-Lily Pond, is one of these preparatory works, some of which were sold during Monet’s lifetime.

After the death of Michel Monet, the son and sole heirof Claude Monet, the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris acquired the Impressionist’s estate.Nearly ninety paintings, many of which Claude Monet had guarded with utmost care, were to find a new home—as Michel Monet stipulated in his last will—“in the Musée Marmottan [as] the largest and most beautiful Monet collection.”

It is therefore fortunate that the ALBERTINA Museum has found a partner in the Musée Marmottan Monet, which has provided forty of its most splendid paintings by Monet for this exhibition. For a short time, the ALBERTINA Museum’s Water-Lily Pond finds itself in the midst of those paintings, in the context of which it was created at the time.

With two other works from the Batliner Collection, which Monet painted inVétheuil and Giverny, as well as over fifty paintings on loan from about forty international institutions and works from private collections, the exhibition traces the life and work of Claude Monet with paintings that are both lavish and colorful, and yet at times also astonishingly chromatically reserved.

Precious international loans

Claude Monet

Young Girls in a Rowing Boat, 1887

Oil on canvas

The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, Matsukata Collection

© The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

The motif for this exhibition’s poster is the monumental work On the Boat, which Monet painted on the water in 1887; it is being shown courtesy of the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

Moscow’s Pushkin Museum is contributing one of the two versions of the Boulevard des Capucines (1873), a strongly elevated view of Paris’s busiest commercial area that lets one take in the big city’s swarming, scintillating, motion-filled atmosphere. (The other is in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City)

Claude Monet

The Boulevard des Capucines, 1873

Oil on canvas

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

© Photo Scala, Florence 2017

As with the nature in Monet’s landscapes, this street is a place of constant activity that changes according to the time of day, the atmosphere, and the weather.

Claude Monet

Grainstack in the Sunlight, 1891

Oil on canvas

Kunsthaus Zürich, acquired from the Otto Meister Bequest, with a contribution from the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt

© Kunsthaus Zürich

Among the impressive loan works, many of which are in large formats, there is also the Grainstack in Sunlight (1891, on loan from Kunsthaus Zürich), which Kandinsky saw in an exhibition on French impressionism and greatly admired. Despite his enthusiasm, however, Kandinsky had difficulty recognizing the motif—an effect that presaged Monet’s emancipation of colors and the advent of abstract painting.

Claude Monet

The Red Kerchief, Portrait of Mrs. Monet, 1873

Oil on canvas

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Estate of Leonard C. Hanna, Jr.

© The Cleveland Museum of Art

Further highlights are Monet’s early winter paintings, including the portrait The Red Kerchief (1873, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA); two paintings of Rouen Cathedral from an extensive series that he created before this Gothic national monument that would themselves become icons of impressionism; and several paintings of the river Creuse in the Massif Central region done in very nasty weather that are pioneering in terms of their composition and use of color.

And from near the end of Monet’s life, by which point his eyesight was severely impaired and he limited himself to working in his garden at Giverny, this exhibition presents

The Japanese Bridge (1918–1924)

and his The House Among the Roses.

Water as a source of inspiration“A Floating World” is the evocative subtitle of the exhibition in the ALBERTINA Museum, the artist’s first large-scale retrospective in Vienna in more than twenty years. The Seine was a home to the pleinairist—both in terms of his various residences and his studio boat, from which he sought to capture the nature and life of the river and its shores with his paintbrush, regardless of the weather conditions.

Guided by one hundred paintings, the exhibition visitor follows in the footsteps of the most important Impressionist along the Seine, pausing at various stations of his life: in Paris, where Monet captured the pulse of modern life with flickering light; in Argenteuil, where he reconciled nature and technology; in Vétheuil, where, in the face of his precarious financial and family situation, he withdrew into solitude to devote himself to unspoiled and original nature; and finally in Giverny, where he arrived at a new aesthetic concept that led Impressionism out of its crisis and paved the way for modern painting.

The river also stands for the many aspects that characterize Monet’s oeuvre: the flowing world of the Japanese woodblock prints that influenced Monet; the coalescing of water, mist, fog, snow, and ice; the colors that change with the weather and lighting conditions; the reflections on the water surface.

The visitor also accompanies Monet to the coasts of Normandy and Brittany, to London and Norway, either to understand his beginnings in Le Havre and his repeated visits to the Atlantic coast, or to visit places together with the artist which promised him new inspiration for his painting.

Wall Texts

Claude Monet was fifty

years old when he finally had his first successes. Yet for his friends he had

always been the uncontested leader of “Impressionism,” the movement that self-confidently

staged its secession from the official Salon under its derisive nickname.

Even before the outbreak of World War I, Monet would become a living legend celebrated as a giant.Monet’s enduring popularity is due to the fact that his painting can be considered the last generally comprehensible form of expression in the visual arts. Given its apparent self-evidence, it is easily overlooked how it changed the visual habits of generations. Bringing light to the canvas, Monet radically rejected academic painting: his random views, sketchy brushwork, and depictions of fleeting moments contradicted the idea of an accomplished and finished painting.

Monet did not find his motifs in the past, but in the immediate present. A witness of his time, he captured the hustle and bustle of modern boulevards and the humble charm of Parisian suburbs, with their smokestacks, bridges, and leisurely Sundays on the banks of the Seine. The greatest plein-air painter of all time committed the changing light to canvas outdoors instead ofthe confinement of his studio.In this retrospective, a hundred paintings trace Monet’s development: from his beginnings in Paris to his stay in Argenteuil and the years in bitter poverty in Vétheuil, where he painted some of the most superb winter and spring landscapes.

This was followed by a period of triumph, the series of the 1890s: the haystacks, Rouen Cathedral, and the Creuse landscapes as the first series Monet painted from a single viewpoint in changing light conditions. For the last thirty years of his life, Monet directed his gaze from close up at the opulent nature of his garden in Giverny: the water lily pond, the Japanese bridge, and the alley of roses.

Argenteuil: 1871 to 1878

As the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 marks a turning point—the transitionfrom monarchy to Third Republic—in French history, these years also led to profound changes in Monet’s personal life: before the outbreak of the war, he married Camille, his companion of many years and mother of his son; seeking to escape military service, the painter fled to London with his young family, where he was inspired by the art of James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Constable and the late work of William Turner.

In London, Monet met Paul Durand-Ruel, his most important art dealer and supporter for many decades to come. In those years, Monet received the inheritance from his recently deceased father and from his wealthy aunt, which ensured his independence. After his return from London, Monet also met the department store magnate Ernest Hoschedé, an influential patron. Monet settled in Argenteuil, a few kilometers outside Paris, where he continued to have a studio.During this period Monet became a keen observer of the shift from the metropolis to the countryside, the changes brought about by industrialization, and railroad traffic and its infrastructure of stations and bridges.

Besides painting intimate genre portraits of of his wife Camille, Monet carried his new landscape interpretation to a first high point. It was also during his years in Argenteuil that the first exhibition of the plein-air painters of modern life took place, who, from 1874 on, were ridiculed as “Impressionists.”

Monet’s pictures of those years show boats on the Seine; a steam engine pulling into the station in deep winter;a fragile bridge construction the artist painted from his studio boat (his own design) in the middle of the Seine; pictures of winter in which he has captured the different temperatures—from biting cold to thaw—in the subtlest nuances. In Argenteuil Monet also adopted the achievement of a flat pictorial layout from the Japanese woodblock prints that were traded on the Paris art market in large quantities.

Argenteuil: The Cradle of Impressionism

In 1871 Monet returned to France from his London exile via Holland and settled in Argenteuil. Whether it was the Zaan in Holland or the Seine in France: the river increasingly became the focus of his attention. Situated on the Seine not far from Paris, Argenteuil was surrounded by asparagus fields and vineyards; industrial plants alternated with embankment promenades; both a railroad bridge and a road bridge crossed the river. The water reflected the smoke of factory chimneys fuming in the distance, the bridges, and a boat hire.

In Monet’s pictures, the strokes describing this mirror image began to develop a life of their own, partly detaching themselves from the concrete motif; the blurring reflections permitted Monet to carry his sketch-like manner of painting further. Moreover, Monet’s garden became increasingly important for him. When moving again in the future, he would always insist on having a garden. Whereas in Argenteuil his garden still existed independently of his painting, Monet would later lay out his garden in Giverny with his painting in mind, subordinating the design of the garden to his art.

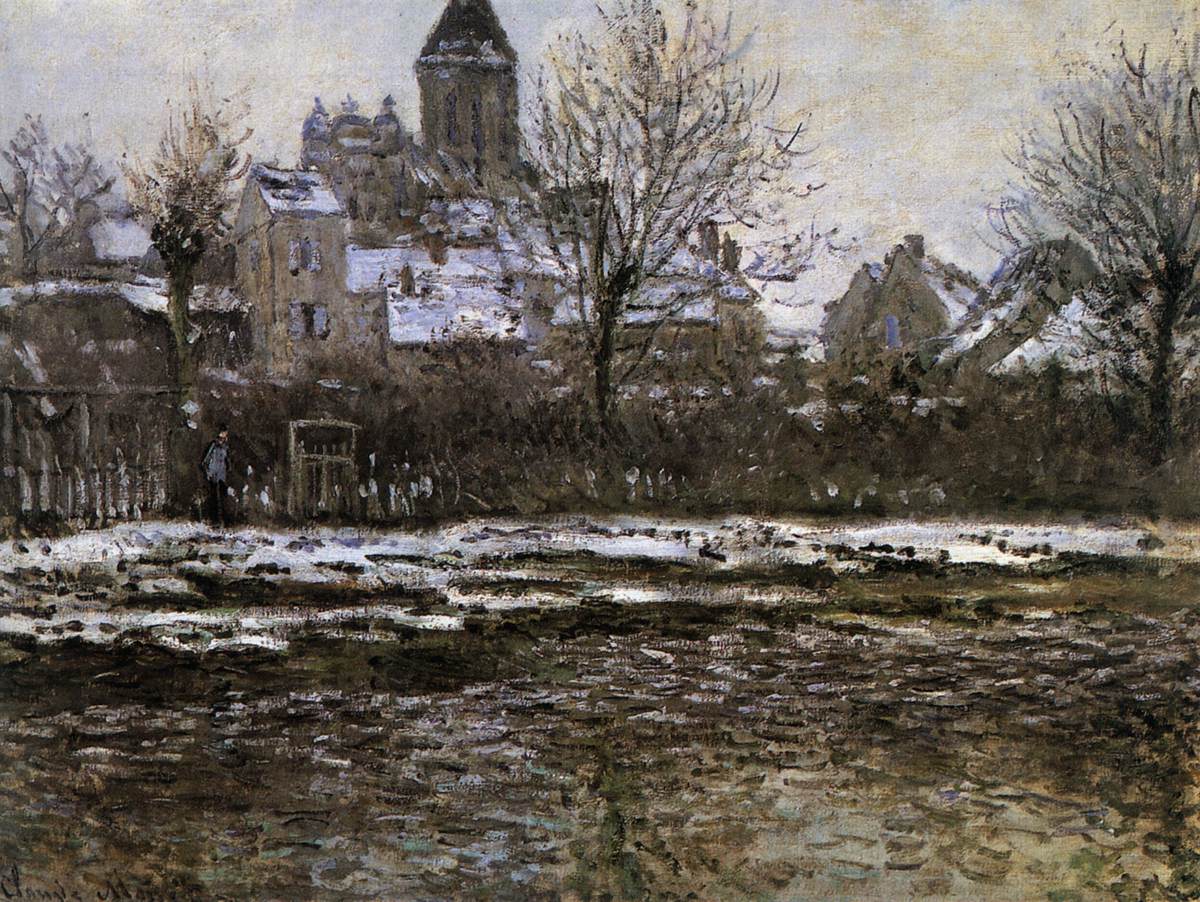

Vétheuil: 1878 to 1881

In January 1878 Monet was forced to leave Argenteuil because of a heavy burden of debt. He had to exchange the Parisian suburb, which could easily be reached by train, for the remote village of Vétheuil. As Monet’s patron Ernest Hoschedé had gone bankrupt with his business, he could no longer support the artist, who was still eyed with suspicion because of his renewal of landscape painting. In March, Monet’s wife Camille gave birth to their second son. Alice, Ernest Hoschedé’s wife, did not follow her ruined husband to Paris, but moved to Vétheuil with her six children, where they shared a house with the Monets. Camille, who was seriously ill, died the following year.

The pictures of the snow-covered Vétheuil and the disastrous ice break of the winter of 1878/79 emanate the deep melancholy and sadness of a life marked by failure and personal misery. Only the spring and summer pictures Monet painted in Vétheuil during those years of great poverty do not betray the unlucky personal fate of the painter, whom his friends already regarded as the Impressionists’ uncontested leader. Monet was too much of an eye for the oppressing situation to obscure his unerring vision of nature.

In 1883 Claude Monet rented a house in Giverny and moved there with Alice Hoschedé and their eight children. Following a period of extensive travels and his first major successes with his series of the Creuse and Rouen Cathedral, the artist was finally able to purchase the small house, a former cider press, in 1890.

After Ernest Hoschedé’s death in March 1891, Monet and Alice married the subsequent year.

The Spectacle of Nature –Journeys of the 1880s

In the 1880s, Monet extended his travels to the whole of France, painting the spectacular coasts of Normandy, the Mediterranean, and Brittany. If Monet had hitherto avoided using famous landmarks as pictorial motifs, in Étretat he began to paint one of the most stunning natural monuments in France: the solitary rock needle and rock gate of Aval, which Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and Gustave Courbet had immortalized before him.

As in Vétheuil and Argenteuil, Monet was interested in the changing appearance of his motifs, caused by different weather conditions, the times of day, and the seasons. He studied the stages of the sunset, with the distant coast increasingly curling into a dark block set against the light. With loose brushstrokes he sought to arrest the individual moment that was so difficult to grasp aesthetically.

Whereas in the following decade Monet would approach the motifs of his famous series—the façade of Rouen Cathedral, the grainstacks, the Houses of Parliament in London, and the hills above the Creuse—from a single perspective and observe how they perpetually changed in the light and atmosphere, on the Normandy coast he still studied his motifs from different viewpoints, both from the distance and from close up. Monet still orbited around his motif, paintingit from various perspectives.

Impression and Completion—The Scandal of Impressionism

The green tone of deep water, the purple glow of wet sand, the dance of thousands of lights as the sun slowly sinks into the sea—nothing escaped Monet’s eye. It also observed how the bright morning light softens the contrasts between colors and bathes the coast in an even light.While working on the French coast, Monet, resorting to the concepts of sprezzatura and non-finito, gave the swiftly painted sketch an autonomy of its own, so that the line between sketch and finished painting became increasingly blurred.

Monet’s art dealer Durand-Ruel disliked overly sketchy paintings, which he considered unsalable. On the other hand, the artist protested that the paintings he delivered were finished all the same.The scandal about Impressionism was closely linked to the reproach of producing unfinished work. Although the oil sketch as an independent art discipline has long found its devotees, in the case of Monet the scandal had to do with his claim that what resembled a preliminary sketchiness actually represented the final work of art. For Monet, the swiftness of painting was in fact proof of the truthfulness with which a momentary mood and atmosphere were captured with due spontaneity and immediacy.

Even before the outbreak of World War I, Monet would become a living legend celebrated as a giant.Monet’s enduring popularity is due to the fact that his painting can be considered the last generally comprehensible form of expression in the visual arts. Given its apparent self-evidence, it is easily overlooked how it changed the visual habits of generations. Bringing light to the canvas, Monet radically rejected academic painting: his random views, sketchy brushwork, and depictions of fleeting moments contradicted the idea of an accomplished and finished painting.

Monet did not find his motifs in the past, but in the immediate present. A witness of his time, he captured the hustle and bustle of modern boulevards and the humble charm of Parisian suburbs, with their smokestacks, bridges, and leisurely Sundays on the banks of the Seine. The greatest plein-air painter of all time committed the changing light to canvas outdoors instead ofthe confinement of his studio.In this retrospective, a hundred paintings trace Monet’s development: from his beginnings in Paris to his stay in Argenteuil and the years in bitter poverty in Vétheuil, where he painted some of the most superb winter and spring landscapes.

This was followed by a period of triumph, the series of the 1890s: the haystacks, Rouen Cathedral, and the Creuse landscapes as the first series Monet painted from a single viewpoint in changing light conditions. For the last thirty years of his life, Monet directed his gaze from close up at the opulent nature of his garden in Giverny: the water lily pond, the Japanese bridge, and the alley of roses.

Argenteuil: 1871 to 1878

As the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 marks a turning point—the transitionfrom monarchy to Third Republic—in French history, these years also led to profound changes in Monet’s personal life: before the outbreak of the war, he married Camille, his companion of many years and mother of his son; seeking to escape military service, the painter fled to London with his young family, where he was inspired by the art of James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Constable and the late work of William Turner.

In London, Monet met Paul Durand-Ruel, his most important art dealer and supporter for many decades to come. In those years, Monet received the inheritance from his recently deceased father and from his wealthy aunt, which ensured his independence. After his return from London, Monet also met the department store magnate Ernest Hoschedé, an influential patron. Monet settled in Argenteuil, a few kilometers outside Paris, where he continued to have a studio.During this period Monet became a keen observer of the shift from the metropolis to the countryside, the changes brought about by industrialization, and railroad traffic and its infrastructure of stations and bridges.

Besides painting intimate genre portraits of of his wife Camille, Monet carried his new landscape interpretation to a first high point. It was also during his years in Argenteuil that the first exhibition of the plein-air painters of modern life took place, who, from 1874 on, were ridiculed as “Impressionists.”

Monet’s pictures of those years show boats on the Seine; a steam engine pulling into the station in deep winter;a fragile bridge construction the artist painted from his studio boat (his own design) in the middle of the Seine; pictures of winter in which he has captured the different temperatures—from biting cold to thaw—in the subtlest nuances. In Argenteuil Monet also adopted the achievement of a flat pictorial layout from the Japanese woodblock prints that were traded on the Paris art market in large quantities.

Argenteuil: The Cradle of Impressionism

In 1871 Monet returned to France from his London exile via Holland and settled in Argenteuil. Whether it was the Zaan in Holland or the Seine in France: the river increasingly became the focus of his attention. Situated on the Seine not far from Paris, Argenteuil was surrounded by asparagus fields and vineyards; industrial plants alternated with embankment promenades; both a railroad bridge and a road bridge crossed the river. The water reflected the smoke of factory chimneys fuming in the distance, the bridges, and a boat hire.

In Monet’s pictures, the strokes describing this mirror image began to develop a life of their own, partly detaching themselves from the concrete motif; the blurring reflections permitted Monet to carry his sketch-like manner of painting further. Moreover, Monet’s garden became increasingly important for him. When moving again in the future, he would always insist on having a garden. Whereas in Argenteuil his garden still existed independently of his painting, Monet would later lay out his garden in Giverny with his painting in mind, subordinating the design of the garden to his art.

Vétheuil: 1878 to 1881

In January 1878 Monet was forced to leave Argenteuil because of a heavy burden of debt. He had to exchange the Parisian suburb, which could easily be reached by train, for the remote village of Vétheuil. As Monet’s patron Ernest Hoschedé had gone bankrupt with his business, he could no longer support the artist, who was still eyed with suspicion because of his renewal of landscape painting. In March, Monet’s wife Camille gave birth to their second son. Alice, Ernest Hoschedé’s wife, did not follow her ruined husband to Paris, but moved to Vétheuil with her six children, where they shared a house with the Monets. Camille, who was seriously ill, died the following year.

The pictures of the snow-covered Vétheuil and the disastrous ice break of the winter of 1878/79 emanate the deep melancholy and sadness of a life marked by failure and personal misery. Only the spring and summer pictures Monet painted in Vétheuil during those years of great poverty do not betray the unlucky personal fate of the painter, whom his friends already regarded as the Impressionists’ uncontested leader. Monet was too much of an eye for the oppressing situation to obscure his unerring vision of nature.

In 1883 Claude Monet rented a house in Giverny and moved there with Alice Hoschedé and their eight children. Following a period of extensive travels and his first major successes with his series of the Creuse and Rouen Cathedral, the artist was finally able to purchase the small house, a former cider press, in 1890.

After Ernest Hoschedé’s death in March 1891, Monet and Alice married the subsequent year.

The Spectacle of Nature –Journeys of the 1880s

In the 1880s, Monet extended his travels to the whole of France, painting the spectacular coasts of Normandy, the Mediterranean, and Brittany. If Monet had hitherto avoided using famous landmarks as pictorial motifs, in Étretat he began to paint one of the most stunning natural monuments in France: the solitary rock needle and rock gate of Aval, which Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and Gustave Courbet had immortalized before him.

As in Vétheuil and Argenteuil, Monet was interested in the changing appearance of his motifs, caused by different weather conditions, the times of day, and the seasons. He studied the stages of the sunset, with the distant coast increasingly curling into a dark block set against the light. With loose brushstrokes he sought to arrest the individual moment that was so difficult to grasp aesthetically.

Whereas in the following decade Monet would approach the motifs of his famous series—the façade of Rouen Cathedral, the grainstacks, the Houses of Parliament in London, and the hills above the Creuse—from a single perspective and observe how they perpetually changed in the light and atmosphere, on the Normandy coast he still studied his motifs from different viewpoints, both from the distance and from close up. Monet still orbited around his motif, paintingit from various perspectives.

Impression and Completion—The Scandal of Impressionism

The green tone of deep water, the purple glow of wet sand, the dance of thousands of lights as the sun slowly sinks into the sea—nothing escaped Monet’s eye. It also observed how the bright morning light softens the contrasts between colors and bathes the coast in an even light.While working on the French coast, Monet, resorting to the concepts of sprezzatura and non-finito, gave the swiftly painted sketch an autonomy of its own, so that the line between sketch and finished painting became increasingly blurred.

Monet’s art dealer Durand-Ruel disliked overly sketchy paintings, which he considered unsalable. On the other hand, the artist protested that the paintings he delivered were finished all the same.The scandal about Impressionism was closely linked to the reproach of producing unfinished work. Although the oil sketch as an independent art discipline has long found its devotees, in the case of Monet the scandal had to do with his claim that what resembled a preliminary sketchiness actually represented the final work of art. For Monet, the swiftness of painting was in fact proof of the truthfulness with which a momentary mood and atmosphere were captured with due spontaneity and immediacy.

The Valley of the Creuse

In 1889 Monet

traveled to Fresselines for the first time in the company of friends. Located on

the plateau above the confluence of the headwaters of the Creuse, the commune

was enclosed by a gloomy and melancholy landscape. Here it was for the first

time that Monet did not paint a series of pictures representing a sequence of

various views of the same place: he gave up the depiction of a single motif viewed

from different spatial perspectives in favor of the depiction of the same motif

viewed at different times. This and the subsequent series—of poplars, grain stacks,

and Rouen Cathedral—are almost necessarily deserted: the observation of a motif

at different times required steady surroundings. In these pictures the lapse of

time and change are brought about without the painter moving back and forth

while the light and the colors alter.

Monet painted the Valley of the Creuse in

the morning, at noon, in damp and cold weather, in bright sunlight, and at

dusk. The differences in the landscape—and later in the façade of Rouen

Cathedral—manifested themselves in ever-smaller time units, so that Monet frequently

worked at three to four canvases simultaneously in order to be able to respond

to changes in the position of the sun and in the atmosphere.

The Late Work at

Giverny

In 1883, Monet moved to Giverny, a small town on the Seine 70 kilometers

west of Paris. He rented an old cider press and orchard, where he lived with

his companion Alice and the children. Crowned by long-overdue success, the

artist was finally able to purchase the estate in 1890. Here he completed two

gigantic panoramas of the gardens of Giverny, which were already a great

attraction during his lifetime: the legendary Grandes Décorations, which he would

eventually donate to the French state after the end of World War I.

It appears

that neither political events, such as the corruption scandal accompanying the construction

of the Panama Canal (1892) or the state crisis triggered by the Dreyfus affair (from

1894 onward), nor personal blows of fate left any traces in Monet’s art: around

the turn of the century, Monet’s stepdaughter, his second wife Alice, and his

son Jean died within a few years. As if Monet were only working for himself, he

devoted himself to the blaze of color in his private refuge with astonishing

exclusiveness.

Whereas the young painter had roamed the countryside in all

kinds of weather to render his motifs from different perspectives, in the 1890s

Monet, now in his fifties, painted his famous series: variations of a motif he

depicted from a single viewpoint and under changing conditions of light and

weather.

In his old age at Giverny, Monet finally devoted himself exclusively

to his opulent flower garden and the alley of roses, the exotic willows, the

Japanese bridge, the wisterias, and the water lily pond. In his late work,

which was revolutionary in terms of theme, composition, and painting technique,

Monet was solely guided by his inner sensations—an approach helped by his

diminishing eyesight due to a cataract. The interpretation of the alley of

roses and the Japanese bridge as a tunnel from which there was no escape

expressed the more-than-eighty-year-old painter’s wish to completely withdraw

from the outside world, his melancholy reading of nature reflecting a life

drawing to a close. Nevertheless, Monet’s dark epilogue gave another fresh turn

to his painting, whose radical modernism would only bear fruit decades after

the death of this great master of plein-air painting.

Monet, Creator and Painter

of His Garden

More than eighty years old, Monet was almost blind when he painted

the series of the alley of roses. Similar to Beethoven, who was forced to

exclusively rely on his inner ear as his hearing deteriorated, Monet had to

resort to his experience when inventing a new, albeit clouded, imagery for the

very last time. No longer was he able to perceive nature’s rich chromatic

spectrum and his own colorful palette.When it became hot under the glass roof

of his studio in the summer, Monet painted the Japanese bridge and the alley of

roses in the garden, where it was cool. The wooden bridge and the iron

trellises shared the tall arch that gave these pictures their basic structure

on which tendrils metamorphosed into sprawling lines of color. Monet took the

flowers up into the air to have them float there weightlessly. He was

interested in the “dematerialization of flowers and plants.”

Biography

Claude Monet is born in Paris in 1840.

He spends his youth in Le Havre. After two years he is exempted from a seven-year

period of military service in Algeria through payment for a substitute. Monet

receives allowances from his family until his father’s death in 1871. During his

studies in Parisian studios he meets his future friends Pierre-Auguste Renoir,

Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille.

In 1867 Camille Doncieux, Monet’s lover and

model, gives birth to their son Jean. The couple marries in 1870. In order to

escape army service during the Franco-Prussian War, Monet flees to London in

1870. He is fascinated by the haze, smoke, and fog in the city on the Thames

and studies the art of John Constable and William Turner.

In 1871 he returns to

France via the Netherlands and for a period of seven years settles in Argenteuil,

a Parisian suburb on the Seine: Argenteuil becomes the cradle of Impressionism,

and Monet is regarded as the “Impressionists’” uncrowned leader. The painter

and his friends receive this derisive nickname in 1874 on the occasion of their

first group exhibition because of the sketchiness of their atmospheric manner

of painting.

In 1878 Monet is forced to leave Argenteuil for Vétheuil, a remote

village on the Seine, because of a huge burden of debt. That same year Camille

gives birth to their second son, Michel. She dies in 1879 after a serious

illness.

After her husband has gone bankrupt, Alice Hoschedé, the wife of

Monet’s former patron, and her six children move in with Monet. It is only

after the death of Alice’s husband that she and Monet legalize their relationship

through marriage in 1892. In this difficult phase of his life, the artist paints

not only melancholy pictures of the snow-covered Vétheuil and the disastrous

ice breakup of 1880, but also sunny spring landscapes.

Having accumulated more

and more debts, Monet also has to leave Vétheuil. In 1883 he rents a small

cider press in Giverny, which he is able to purchase in 1890.

In the 1890s Monet

paints his famous series, which finally earn him success and fame: the Creuse

landscapes, the haystacks, and Rouen cathedral.

However, his real passion lies

in painting his garden in Giverny, which he gradually enlarges. These pictures reveal

nothing of the painter’s personal blows of fate: the deaths of his stepdaughter

in 1899, his second wife in 1911, and his first son in 1914. Neither does

Monet’s withdrawn late work reflect the French state’s serious crises, not even

World War I. The artist has long been considered a living legend and one of

France’s national monuments.

With his vision heavily impaired through a

cataract, Monet bathes his pictures in the colors of late autumn during his

final years. These gloomy and almost abstract paintings only become known after

Monet’s death in 1926.

Your chosen press images are now ready for download under the following link:https://www.albertina.at/en/press/?token=amRrQHF1ZXVlaW5jLmNvbXwxNTQyMDc0MTUx

Claude Monet

On the Beach at Trouville, 1870

Oil on canvas

Museé Marmottan Monet, Paris

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Claude Monet

Train Engine in the Snow, 1875

Oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Claude Monet

Water Lilies, 1907

Oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Claude Monet

The Studio Boat, 1874

Oil on canvas

Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Claude Monet

Rouen Cathedral, Sunlight Effect, 1894

Oil on canvas

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Claude Monet

The Landing Stage, 1871

Oil on canvas

Acquavella Galleries

© Acquavella Galleries

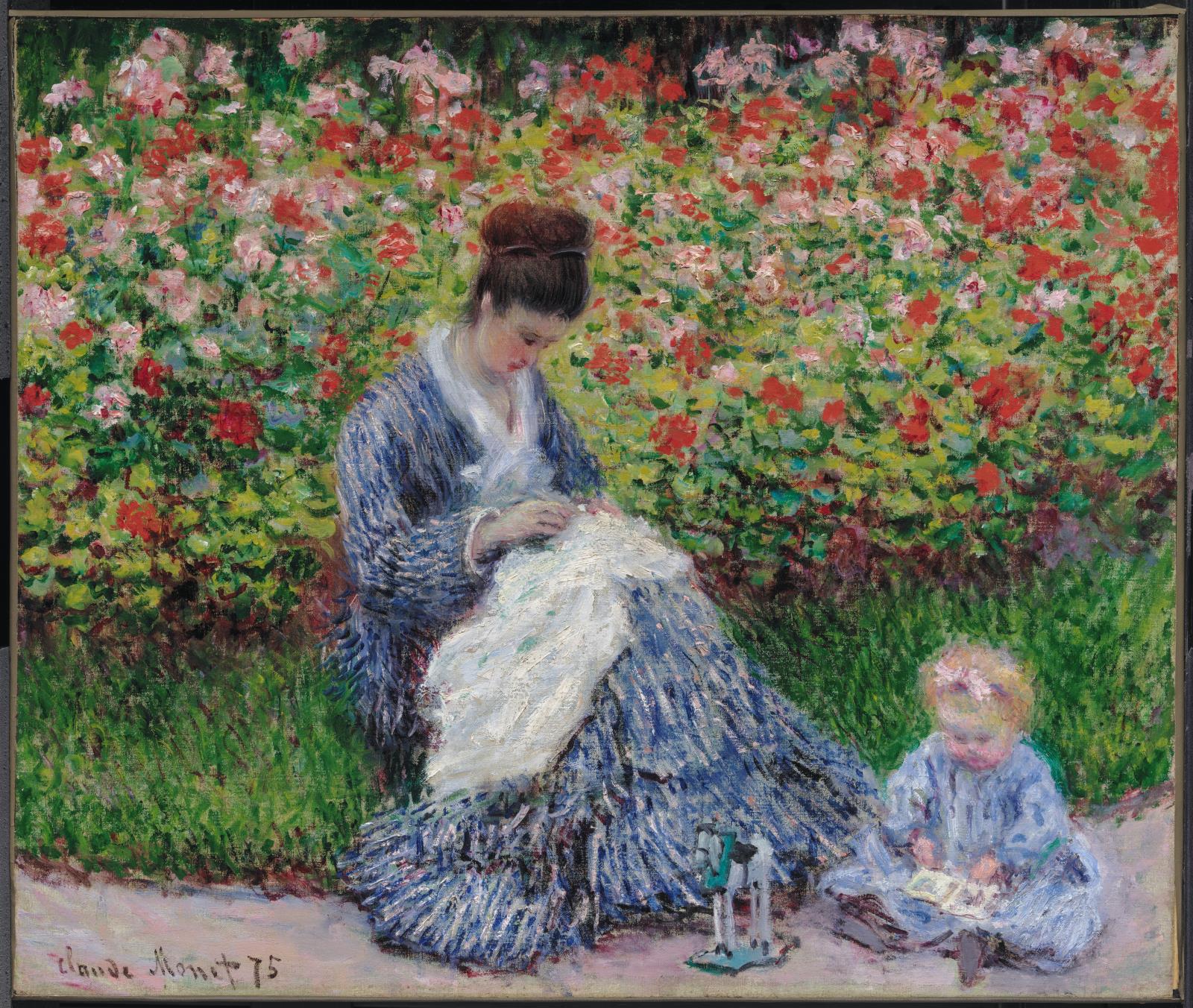

Claude Monet

Camille Monet and a Child in the Garden, 1875

Oil on canvas

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, anonymous gift in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin S. Webster

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Claude Monet

Water Lilies, 1908

Oil on canvas

Callimanopulos Collection

© Callimanopulos Collection, photo: Ugo Bozzi Editore Srl, Rome

Claude Monet

Water Lilies, 1916-1919

Oil on canvas

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel Sammlung Beyeler; Photo: Robert Bayer

Claude Monet

The Church at Vétheuil, Snow, 1878/1879

Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

© RMN-Grand Palais/Musée d’Orsay/Stéphane Maréchalle

Claude Monet

Lane in the Poppy Field, Île Saint-Martin, 1880

Oil on canvas

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Estate of Julia W. Emmons

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Claude Monet

Breakup of Ice, Gray Weather, 1880

Oil on canvas

Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon – Founder’s Collection

© Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Catarina Gomes Ferreira

Claude Monet

The Rock Needle Seen through the Porte d’Aval, 1886

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; gift from the Marjorie and Gerald Bronfman Collection, Montréal

© National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa