In 1857,

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his friend

William Morris headed to Oxford, to paint the murals in the new debating chamber of the Oxford Union.

On

a break from work one evening, Rossetti went to the theatre — and was

captivated by a fellow audience member, a 17-year-old beauty called Jane

Burden. This local ostler’s daughter so entranced him that, immediately

after the show, Rossetti asked if she’d become his model. Just two

years later, it was Morris whom Burden married, rather than Rossetti.

There

developed a love triangle that would change the course of British art

in the late 19th century. Jane would ultimately sit for a host of works

by Rossetti, including

Proserpine: a painting the artist himself referred to as his ‘very favourite design’. On October 28, Christie’s offers an 1878 version of

Proserpine as part of its

European Art Part I sale in New York.

The

image is inspired by Classical mythology: specifically the tale of

Proserpine, the beautiful but unwilling wife of Pluto, god of the

underworld, who had found her picking flowers in the vale of Nysa, and

abducted her.

The king of the gods, Zeus, granted

Proserpine’s mother, Ceres, permission for the girl to return to Earth,

on the condition that she’d eaten nothing in the underworld. Alas — and

this is the moment captured by Rossetti — Proserpine had eaten

six pomegranate seeds. The upshot was that she’d spend only half of the

year on Earth, and the other half beneath it (one month with Pluto for

each pomegranate seed consumed).

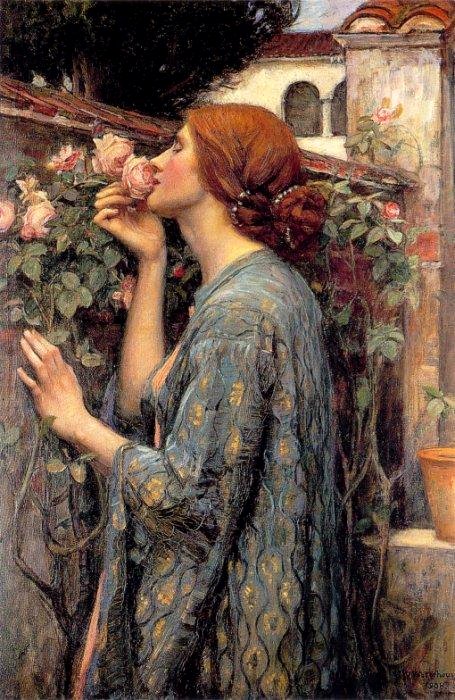

Posing as Proserpine,

Jane Morris sports long dark brown tresses and a flowing blue robe.

Viewed in three-quarter profile, she looks out of the picture

enigmatically, holding the offending fruit in her left hand. She seems

somehow aware that she has erred, her right hand catching the wrist of

her left, as if to prevent the eating of further seeds.

As

he does in many single-figure paintings of heroines, Rossetti thrusts

Proserpine to the front of a tight, claustrophobic space (other examples

include

The Day Dream, for which Jane modelled; and

Bocca Baciata, for which she didn’t). By compressing the scene like this, he emphasises his subject’s captivity.

The

artist worked hard on the picture, telling his friend G.P. Boyce that

he had ‘begun and rebegun it time after time’. Each element was

painstakingly considered: from the sonnet about Proserpine, written by

Rossetti himself and inscribed in the top right, to the spray of ivy

curving down the painting’s left. The plant, which typically clings to

its support, was said by Rossetti to symbolise the heroine’s ‘clinging

memory’ of life on Earth.

As for the shaft of light on

the rear wall, this is left ambiguous. Is it the fading light of her

beloved Earth, as Proserpine awaits a dark future with Pluto? Or is it

actually a symbol of hope, for the happy months of the year she’s

allowed back in the world above?

John R. Parsons, portrait of Jane Morris, 1865. Photo: The Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman Images

Although it is derived from classical myth, Proserpine is

almost always interpreted autobiographically: which is to say, in terms

of the love triangle between Jane, William Morris and Rossetti.

When

the two men first met her, Rossetti — the co-founder of the

Pre-Raphaelite movement — was already engaged to another woman,

Lizzie Siddal.

Despite his attraction to Jane, he married Lizzie in 1860. Only two

years later, however, Siddal died from an overdose of laudanum.

Jane

was by now not just Morris’s wife but colleague, taking charge of

textile embroidery at his celebrated design firm, Morris, Marshall,

Faulkner & Co. The marriage was far from blissful, however. From the

mid 1860s on, Jane modelled for a number of Rossetti’s paintings

(another famous example being

Mariana) — and became his lover, too.

Liaisons

were made easier when Morris and Rossetti signed a joint lease on a

country retreat in the Cotswolds called Kelmscott Manor. The former was

often away — taking extended trips to Iceland in 1871 and 1873, for

example — meaning his wife and friend were able to spend large periods

of time together alone.

‘Beauty like hers is genius,’

Rossetti claimed. As a woman trapped in an unhappy marriage,

Proserpine’s predicament neatly reflected Jane’s own — certainly in

Rossetti’s eyes. That panel of light might also represent the happiness

that might have been, had Jane and Rossetti ever married.