Godfried Maes. Head of Medusa, 1680. The Art Institute of Chicago, Prints and Drawings Purchase Fund.

Drawing reached one of its pinnacles in the Netherlands during the 17th century—a period commonly known as the Golden Age. While early modern Dutch and Flemish art typically focus on the paintings created during this time, this exhibition constructs an alternative narrative, casting drawings not in supporting roles but as the main characters. Featuring works by Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, Hendrick Goltzius, Gerrit von Honthorst, Jacques de Gheyn II, and many others, the show traces the development of drawing in this period, exploring its many roles in artistic training, its preparatory function for works in other media, and its eventual emergence as a medium in its own right.

The 17th century brought change to the northern and southern Netherlands, including political upheaval and scientific innovation. The effects of these changes had a great impact on art—what kind of art was in demand, who could and did produce art, and where and how art was made. Most artists in 17th-century Netherlands chose their career through family connections, training with a relative who worked in an artistic trade, although there are significant exceptions to this trajectory—Rubens was the son of a lawyer and Rembrandt the son of a miller.

Hendrick Avercamp, “Two Old Men beside a Sled Bearing the Coats of Arms of Amsterdam and Utrecht”, ca. 1620-1633

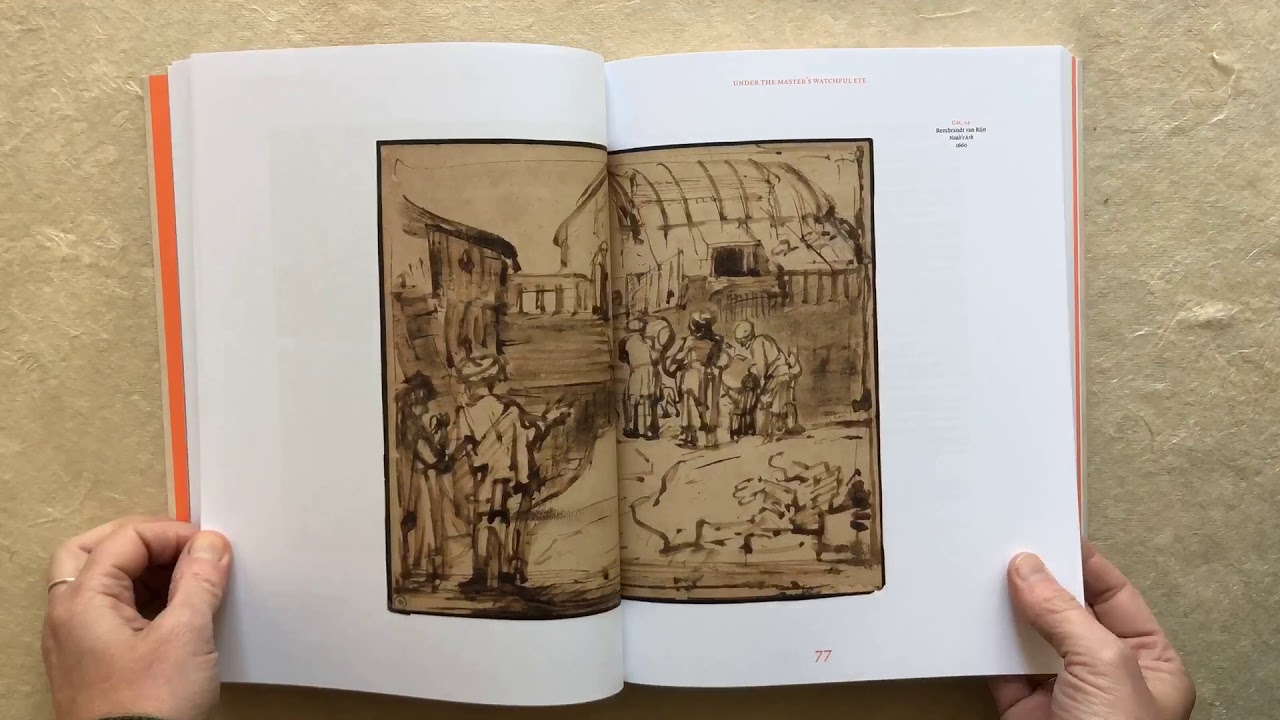

Abraham Bloemaert, Rubens, and Rembrandt supervised the three most important workshops of the period, overseeing the development of dozens, if not hundreds, of students. In these workshops, learning to draw was essential. The ability to accurately depict the human face and body was critical to an artist’s success and was especially important for those who aspired to create history paintings—the genre considered most prestigious because it relied on literary sources and often required portraying multiple figures in complex and dramatic scenes.

Rembrandt, more than other artists of this period, embraced life drawing. Most notably, he pioneered the collective study of the female nude—a commonplace practice today, but one that challenged the bounds of decency in the 17th century. Studying the live figure increasingly became standard practice in the Netherlands during this period, but it was generally restricted to drawing male models, since prevailing cultural norms made it difficult for artists to find women to pose for them, especially in the nude. Among the most celebrated of all Rembrandt’s drawings is a rare study of a female nude, which is featured in this exhibition. An emotive and striking work, it highlights the importance for artists of the period to learn to draw the female figure.

Although drawings in the 17th century served many purposes—as reference materials, studies for future paintings, preparatory designs for prints—they also emerged as independent works of art, bought, commissioned, and collected by wealthy merchants. Produced in a broad range of media, including chalk, ink, and watercolor, the drawings in this exhibition are captivating examples of artistic skill and imagination. Together they provide a new view of the creativity and working process of Netherlandish artists in the 17th century and reveal how drawings came to be the celebrated works of art we know them to be today.

The Art Institute’s collection of Dutch and Flemish drawings - one of the museum’s best kept secrets - has never been exhibited together before or understood and interpreted as a coherent group. This exhibition and its beautiful accompanying catalogue reveal, for the first time, the remarkable strength and importance of our holdings in this area.

Catalogue

356 pages, 8 x 10 1/2

218 color + 43 b/w illus.

ISBN: 9780300247077

PB-with Flaps

Distributed for the Art Institute of Chicago

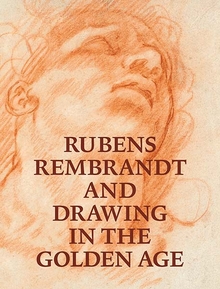

Rubens, Rembrandt, and Drawing in the Golden Age

An extraordinary history of Netherlandish drawing, focused on the training and skill of artists during the long 17th century

With a lively narrative thread and thematic chapters, this book offers an exceptional introduction to Dutch and Flemish drawing during the long 17th century. Victoria Sancho Lobis discusses the many roles of drawing in artistic training, its function in the production of works in other media, and its emergence as a medium in its own right. Beautifully illustrated with some 120 drawings by artists including Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, Hendrick Goltzius, Gerrit von Honthorst, and Jacob De Gheyn, this book surveys current methodologies of studying these works and features a brief history of Dutch papermaking and watermarks as well as a glossary. Paying careful attention to materials and techniques, and informed by recent conservation treatments, Lobis explains how to look at these drawings as records of experimentation and skill, true windows into the artist’s mind.

Victoria Sancho Lobis

served as curator in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Art

Institute of Chicago from 2013 to 2017 and is guest curator of this

exhibition. She is also currently a lecturer in the History Department

at Claremont McKenna College.