CLARK ART INSTITUTE

JUNE 10-October 15

Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany

November 18, 2023–April 1, 2024

Munch Museum (MUNCH), Oslo, Norway

April 27–August 24, 2024

The Clark Art Institute presents the first exhibition in the United States to consider how the noted Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863–1944) employed nature to convey meaning in his art. Munch is regarded primarily as a figure painter, and his most celebrated images (including his iconic The Scream) are connected to themes of love, anxiety, longing, and death. Yet, landscape plays an essential role in a large portion of Munch’s work. Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth considers this important, but less explored aspect of the artist’s career. The Clark is the sole U.S. venue for the exhibition which opens on June 10 and is on view through October 15, 2023. Organized in collaboration with the Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany and the Munch Museum (MUNCH), Oslo, Norway, the exhibition is presented in Potsdam from November 18, 2023–April 1, 2024, and in Oslo from April 27–August 24, 2024.

“This fascinating exhibition provides a fresh opportunity to explore the range and depth of Edvard Munch’s art,” said Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director of the Clark. “Although many people make immediate associations and assumptions regarding Munch’s work, this exhibition offers a considerably different look at the artist that encourages us to expand our understanding and deepen our appreciation of his exceptional talents. For the Clark, the opportunity to explore Munch’s perceptions of nature against the backdrop of our own beautiful natural setting is particularly compelling.”

The exhibition is organized thematically to show how Munch used nature to convey human emotions and relationships, celebrate farming practice and garden cultivation, and explore the mysteries of the forest even as his Norwegian homeland faced industrialization.

Trembling Earth features seventy-five objects, ranging from brilliantly hued landscapes and three stunning self-portraits, to an extensive selection of his innovative prints and drawings, including a lithograph of The Scream. The exhibition includes more than thirty works from MUNCH’s world-renowned collection, major pieces from other museums in the USA and Europe, and nearly forty paintings, prints, and drawings from private collections, many of which are rarely exhibited.

“This exhibition draws on new research to offer a fresh perspective on Munch’s career,” said Jay A. Clarke, Rothman Family Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. “Alongside depictions of death, existential torment, and troubled relationships, Munch also created imagery reflecting his knowledge of science, showing his embrace of pantheism, and a deep reverence for nature.” Clarke led the curatorial project for the Clark and began early work on the exhibition when she served as its Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs from 2009–2018.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

This exhibition introduces Munch’s lesser-known landscape paintings and considers his iconic figural images from a new perspective, by focusing on how his rendering of nature animated his chosen narratives. In paintings of the Oslo Fjord shoreline and the Baltic coast of Germany, Munch explored changes brought about by increased tourism, partially the result of health reform initiatives extolling the virtues of outdoor activity. Munch developed his own pantheistic worldview that connected human biology, plant life, and the solar system. Munch’s fascination with humankind’s interaction with the earth and the impact of one on the other can be seen in a selection of landscape-rich prints, drawings, and paintings from the 1890s to the 1940s.

“It is with great pride that the MUNCH Museum participates in this substantial exhibition of Edvard Munch's art, where the public can gain insight into his strong relationship to nature. It is also a great pleasure to participate in a network of skilled professionals from the U.S., Germany, and Norway, collaborating to bring forward new knowledge about one of Norway's greatest artists. I am sure that the exhibition and the insightful catalogue that accompanies all three venues will be well received by the public,” said Tone Hansen, director of MUNCH. “MUNCH is a museum for modern and contemporary art, and manages and preserves the legacy of Edvard Munch for an international public. An exhibition series like this one demonstrates the importance of Munch’s work, the value of collaboration, and the importance of new research and insight.”

Ortrud Westheider, director of the Museum Barberini said: “Munch’s works are still unsurpassed in their emotional expressiveness and overwhelming modernity, and for good reason: for many people, his art is a symbol of their own feelings. With the first exhibition devoted exclusively to Munch’s landscape depictions, we are opening up a facet of his oeuvre that has hitherto been little represented, and the dramatic weather conditions in his paintings take on a special urgency, especially against the backdrop of the looming climate catastrophe.”

IN THE FOREST

Munch’s depictions of forests include emotional encounters between couples, children approaching dense woods, and scenes of Norway’s logging industry. In prints of the 1890s and 1910s, such as

Ashes I (1896)

1897

1915

and Towards the Forest (1897 and 1915),

a dense thicket of wood often served as a backdrop for scenes of impending liaisons or extinguished love. In his diaries and other writings, the artist suggested the woods as a place where love could either collapse or prompt intimacy.

The Fairytale Forest (1927–29), one of a number of works on this theme painted from 1901 through the late 1920s, shows small children walking towards an imposing forest. The claustrophobic depiction of children surrounded by towering dark spruces is heightened by the acid-green colors, the differences in scale, and the anthropomorphic shape of the trees, whose branches resemble a gaping mouth.

Edvard Munch, The Yellow Log, 1912, oil on canvas. Munchmuseet, MM.M.00393, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Munchmuseet

Edvard Munch, The Yellow Log, 1912, oil on canvas. Munchmuseet, MM.M.00393, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Munchmuseet

The Yellow Log (1912)

and The Logger (1913) draw attention to both the growth of trees and destruction of Norway’s forests. The Yellow Log depicts a group of felled trees in a dense forest, the brightly-hued large central tree dramatically disappearing into the vanishing point of the canvas. The surrounding trunks are shaded purple with dark, cellular-shaped circles demarcating their bark and emphasizing the life force within them.

CULTIVATED LANDSCAPE

Munch’s paintings of cultivated landscapes could be seen as reactions against the intense urbanization and modernization that occurred during his lifetime. In particular, farming subjects demonstrate Munch’s quest for alternatives to the alienating conditions of city life. During a time when Norwegian agriculture was undergoing modernization and mechanization, Munch preferred to depict traditional small-scale farming practices, celebrating the farmer’s “simple” way of life, as in

The Haymaker (1917).

shows a male and female laborer posed on either side of a tree, suggesting a harmony between the sexes.

The artist drew inspiration from the fertile coastal area around the Oslo Fjord, where he rented or owned properties in locations such as Åsgårdstrand, Kragerø, and Hvitsten. Reflecting a horticultural boom in Norway, Munch created flower and kitchen gardens, planted fruit trees and kept animals such as hens, ducks, and horses at his various homes. The artist’s final property at Ekely, on the outskirts of Oslo, included a productive garden where he planted vegetables during World War I to supply his family and friends with fresh produce. He later let the gardens run wild, with trees dripping with fruit, as featured in

Apple Tree in the Garden (1932–42).

In Woman with Pumpkin (1942) Munch pairs the woman with the lush abundance of the garden.

The artist regarded his gardens and fields as places of refuge overflowing with life. They can also be understood as liminal zones between nature and civilization. In a notebook, Munch described the female figures who populate his paintings of gardens as “brightly dressed women from the city.” The formally dressed woman who appears in

Girl Under Apple Tree (1904) seems out of place in the verdant setting, and perhaps signals the contemporary expansion of tourism in the resorts around the Oslo Fjord.

STORM AND SNOW

Munch’s fascination with metamorphosis, together with his faith in nature’s cyclical renewal, led him to depict each season with reverence. Climate anxiety at the beginning of the twentieth century involved very different concerns to those that preoccupy us today. The prevalent fear was not that temperatures would rise, but that the earth would be engulfed by a new Ice Age. As an avid newspaper reader, Munch would have been aware of this trend, although his depictions of snow and ice are not overtly pessimistic. His paintings of snowy landscapes celebrate the mystery and wonder of Norway’s long, dark winters. The large-scale evening vistas, painted in hues of white and blue, feature starry night skies and sturdy pine trees impervious to the bitter cold. The snowcapped forests, townscapes, and moonlit winter skies in paintings such as

White Night (1900–01)

and Starry Night (1922-24) convey a sense of quiet awe.

Starry Night depicts a magnificent frozen landscape beneath the starlit canopy of a night sky. The perspective is from the artist’s veranda at his home in Ekely, where he looked out over the winter landscape of his fields and garden, contemplating the sky that arches over the distant lights of the city.

Munch also depicted extreme weather events during the warmer months, as in

The Storm (1893)

and Stormy Landscape (1902–03), allowing him to explore tumultuous conditions like waving trees and swirling clouds. For all his awareness of humankind’s imprint on nature and interconnectedness with the universe, Munch’s paintings of snow, storm, and ice present nature as a force that is ultimately beyond human control.

ON THE SHORE

The shoreline was an important motif for Munch, as he lived on or near the Oslo Fjord coast much of his adult life. Munch depicted its curving shoreline in his paintings, drawings, and prints from the 1890s through the 1930s. It became a recurring theme, one he identified with the “perpetually shifting lines of life.” In some depictions, the shoreline itself was the subject, as in

Summer Night by the Beach (1902–03), and in others it was a backdrop amplifying human emotion, as in

Two Human Beings, the Lonely Ones (1899). The coastline featured most prominently in Munch’s works depicting themes of melancholy, human isolation, and physical separation.

One narrative theme that employed the shoreline was that of a man and woman parting from one another.

Separation II (1896) focuses closely on a couple, showing only their heads, shoulders, and the shoreline winding between and behind them. The woman faces the water and strands of her hair, echoing both the waves and curving shore, flow towards the man, her tresses touching his head and shoulder, and settling near his heart. The man, eyes closed and head turning away from the water, seems defeated yet inextricably connected to the woman.

Another frequent subject the artist set on the shoreline was a dejected man or woman facing the water. While the figure was most often male, Munch’s Melancholy II (1898) woodcut depicts a woman. The woman throws her head into her hands with hair cascading downwards. Her red dress, with the anthropomorphic shape of an open mouth, echoes the curving shoreline, its borders emphasized by the black background. By setting depictions of separation, attraction, and loneliness against the winding and jagged coast of the fjord, Munch infused his pictures with vitality and emotion.

CYCLES OF NATURE

Munch’s artistic practice was affected by his overlapping interests in philosophy, religion, and the natural sciences. Although raised in a staunchly Christian household, in adulthood Munch’s religious views were shaped by scientific theories of Darwinian evolution and Monism, a philosophical belief that all existence is unified: animal, vegetal, and terrestrial. The position of humans as part of a cosmic cycle is a recurrent theme in his art, one often associated with the image that has become synonymous with modern anxiety,

The Scream (1895).

A lithograph of the artist’s most celebrated work—one of about only thirty made—is on view in the exhibition.

The Scream has generally been interpreted as an outward expression of an interior mental state. Seen alongside

The Sun (1912), however, its connection to the universal force of nature becomes more evident. In The Scream, a figure confronts the viewer with staring eyes and mouth agape. Even more importantly, the figure is depicted as part of the churning, trembling landscape behind. The rhythm of the lone figure’s swaying body continues into the pulsating landscape. Nature is alive, like a human being, and they mutually impact each other. The German inscription included on the lithograph translates to “I felt the great scream through nature.”

Munch’s long-standing fascination with the existential meaning of nature culminates in the motif of the sun. Painted with magnificent energy, the beams of light of The Sun (1912) are rendered in strong hues of orange, yellow, white, and green, piercing the earth below, infusing the rocks, water, and soil with energy. In related works, the artist linked humankind to nature and the cosmos with images of people stretching upwards towards the sun, a symbol of life and enlightenment.

Several works depict the cycles of nature directly, for example in the form of rotting bodies that provide nourishment to sprouting plants. In his 1896 drawing

Metabolism (Life and Death), plants with anthropomorphic features grow out of the corpse of a woman. In the background, a pregnant woman is surrounded by plants and trees. The sun’s rays shine upon her body, nourishing the baby growing within her as well as the surrounding plants. They suggest that the boundaries between humanity and nature are blurred—we do not stand outside the cycle of nature, we are part of it. There are no clear distinctions between internal and external, material and non-material, living and dead.

CHOSEN PLACES

Throughout his life, specific geographic sites impacted Munch and his artistic production. These places where Munch lived and worked for periods of time became protagonists in his paintings, prints, and drawings, distinct with their own visual characteristics and inspired narratives.

In his paintings of Åsgårdstrand, the Norwegian village where Munch spent many of his summers, the artist depicted the rocky, curving shoreline when looking away from the village, as in

Beach (1904). He also looked inland, shifting his focus to young girls and women standing on the town’s pier in front of the Kiøsterud Manor, one of the grandest buildings in the town. One of Munch’s most iconic and repeated motifs is

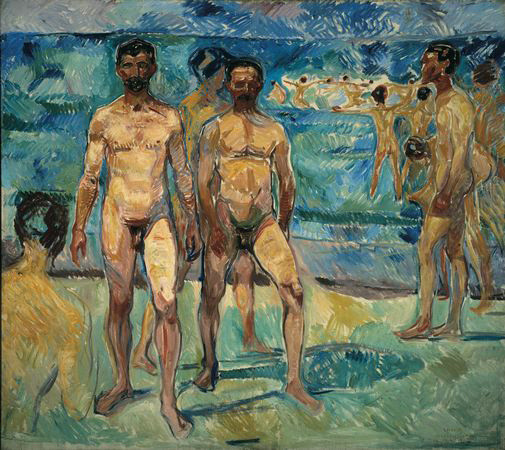

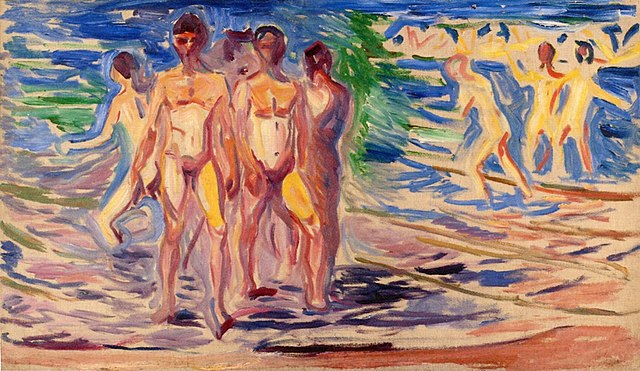

Munch spent an intense period from 1907 to 1908 in Warnemünde, on the northern coast of Germany, where he sought water cures and rest for his frayed nerves just prior to being hospitalized for alcoholism and a nervous breakdown. Here, he created

Bathing Men (1907–8), which became the central panel in a series of five known as

The Ages of Man. Bathing Men depicts a group of nude, muscular middle-aged men walking toward the viewer, playing in the waves, and strolling along the shore. The scene is one of healthful vitality.

In 1910, Munch bought property on the Oslo Fjord in Hvitsten, where he created bathing scenes and built outdoor studios for his monumental works. As Munch embraced the healing effects of sun and the outdoors, his color palette brightened, as in works like Bathing Man (1918). In this period, his contemporaries began to perceive the artist as happier: at peace with himself and at one with nature.

Catalogue

The exhibition also marks the publication of Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth, a 248-page catalogue with contributions by Ali Smith, Jay A. Clarke, Jill Lloyd, Trine Otte Bak Nielsen, and Arne Johan Vetlesen.

The book is published by MUNCH, Oslo, Norway and distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven.

A thought-provoking volume on Munch’s often neglected depictions of nature, this richly illustrated catalogue provides a multifaceted perspective on Munch’s images of the natural world, exploring the Norwegian artist’s landscapes, seascapes, and existential environments in light of his own time and ours.

.jpg/640px-Edvard_Munch_-_The_storm_(1893).jpg)

.jpg/640px-Edvard_Munch_-_Summer_night_by_the_beach_(1902-03).jpg)

_(8477718108).jpg/640px-Edvard_Munch-_The_Scream_(1895%2C_signed_1896)_(8477718108).jpg)

.jpg/640px-Edvard_Munch_-_The_Girls_on_the_Bridge%2C_Hamburger_Kunsthalle_(1901).jpg)

.jpg/640px-Edvard_Munch_-_Pikene_p%C3%A5_broen_(1902).jpg)