Centre Pompidou

28 MARCH - 16 JULY 2018

Jewish Museum, New York

14 September 2018 to 2 January 2019

The Centre Pompidou is offering audiences a chance to explore a chapter in the history

of modernity and the Russian avant-garde: the period of the people's art school (1918 - 1922) founded by Marc Chagall in his native city of Vitebsk, which now lies in Belorussia.

2018 marks the one hundredth anniversary of Chagall’s appointment as Fine Arts Commissioner

for the Vitebsk region: a position that enabled him to carry out his project for an art institute open

to everyone. El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich, leading exponents of the Russian and Soviet avant-garde, were two of the artists Chagall invited to teach at the school. A period of feverish artistic activity followed, turning the school into a revolutionary laboratory.

Marc Chagall, Cubist landscape, 1918; Liozna, near Vitebsk, BelarusThe exhibition retraces these fascinating post-revolutionary years when the history of art was shaped in Vitebsk, far from Russia's main cities.

Through 250 works and documents loaned by the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg, museums in Vitebsk and Minsk and major American and European collections, the exhibition presents the output of three iconic figures – Marc Chagall, El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich – as well as works by students and teachers of the Vitebsk school, like Vera Ermolayeva, Nikolai Suetin and Ilya Chashnik.

A catalogue of 280 pages and some 280 illustrations, edited by Angela Lampe, the exhibition curator,

is being published by the Centre Pompidou. This major publication includes essays by international experts (including Aleksandra Shatskikh and Jean-Claude Marcadé), a compilation of French translations of hitherto unpublished Russian texts, and a detailed chronology.

The exhibition is being produced in collaboration with the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

After the Centre Pompidou, it will be on show in a modified version at the Jewish Museum in New York, from 14 September 2018 to 2 January 2019.

Introduction to the exhibition

Living in Petrograd at the time, Marc Chagall was a first-hand witness of the Bolshevik revolution that turned Russia upside down in 1917. The passing of a law that did away with all national and religious discrimination gave him, as a Jewish artist, the status of full Russian citizenship for the first time.

He then entered an ecstatic period of creativity, producing a series of monumental masterpieces.

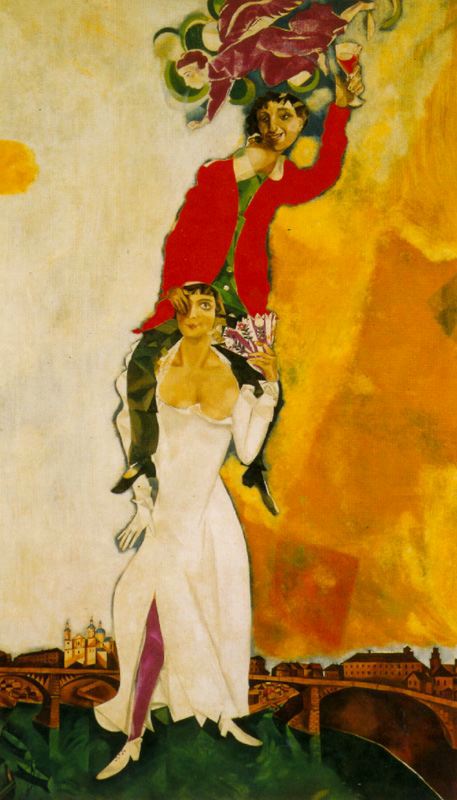

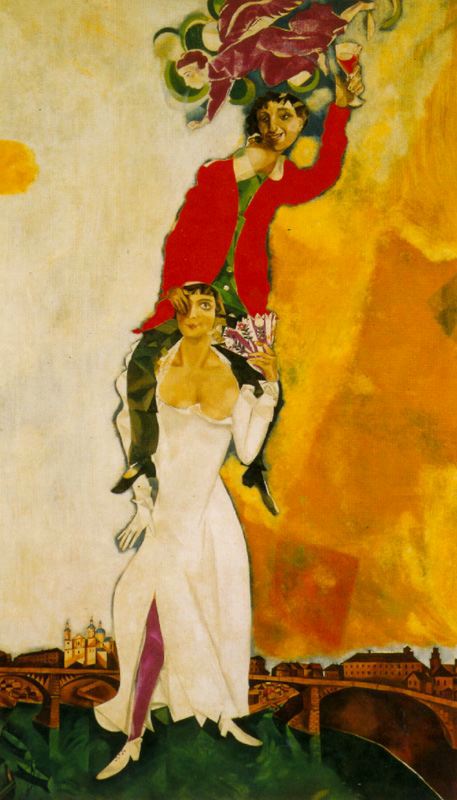

Each of these large paintings seems like a hymn to the Chagalls' happiness, such as

"The Double Portrait with a Glass of Wine" of 1917,

and "Above the City" of 1918, showing the two lovers, Chagall and his wife Bella, flying off into the clouds, free as air. Everything exudes his euphoria at the time.

As the months went by, however, Chagall felt compelled to help young residents of Vitebsk lacking an artistic education, and to support other Jews from humble backgrounds, like himself. He then conceived the idea of creating a revolutionary art school in his city, open to everyone, free of charge and with no age restriction. His project, which also included the creation of a museum, was the perfect embodiment of Bolshevik values, and was approved in August 1918 by Anatoly Lunacharsky, head of the People's Commissariat for Education. A month later, he appointed Chagall as Fine Arts Commissioner, initially tasking him with organising the festivities for the first anniversary of the October Revolution.

Chagall invited all the artists of Vitebsk to make panels and flags based on preparatory drawings, several of which have survived. In his autobiography, "My Life", Chagall later wrote:

After the celebrations, the Commissioner poured his entire energy into creating his school, and it was officially inaugurated on 28 January 1919. Chagall, though admired by his students, had to struggle somewhat to get his establishment up and running.

The first teachers began to leave, like Ivan Puni; meanwhile others arrived, like Vera Ermolayeva, the future director, and most importantly, El Lissitzky, who took charge of the printing, graphic design and architecture workshops. He pushed his friend Chagall to bring in the leader of the abstract movement, Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprematism. It did not take long for this extraordinary, charismatic theorist to galvanise the young students after his arrival in November 1919. He rapidly formed a group with teachers who sympathised with the new movement: Unovis ("champions of new art"). One of their slogans was "Long live the Unovis party, which asserts new forms of Suprematist utilitarianism."

The collective began to design posters, magazines, streamers, signs and ration cards. Suprematism infiltrated every sphere of social life. Its members became involved in the presentation of festivities, and their work decorated trams, façades and speakers' rostrums. Colourful squares, circles and rectangles invaded the city's walls and streets.

Suprematist abstraction became the new paradigm of not only the school but the world in general. Lissitzky, as a trained architect, played a crucial role in all this. With his extraordinary Proun series (projects for asserting the new in art), he was the first to extend architectural volume to the pictorial plane of the Suprematists, considering the series as "stations where one changes from painting to architecture". Meanwhile, during his years in Vitebsk, Malevich began to abandon painting – an exception being his magisterial Suprematism of the Spirit – in favour of his main theoretical writings and education.

A methodical and stimulating teacher, he attracted ever more students, while Chagall found himself increasingly isolated. His dream was to develop a revolutionary art independent of style: the dual principle that had guided him in filling his museum and organising the first public exhibition in December 1919, where paintings by Vassily Kandinsky and Mikhail Larionov were seen alongside the abstract works of Olga Rozanova.

But this dream came to an end in the spring of 1920. With his classes slowly emptying of students, Chagall decided to leave Vitebsk in June and went to live in Moscow, where he worked for the Jewish theatre. Deeply upset by this setback, he held a grudge against Malevich, believing that he had plotted against him.

After the Centre Pompidou, it will be on show in a modified version at the Jewish Museum in New York, from 14 September 2018 to 2 January 2019.

Introduction to the exhibition

Living in Petrograd at the time, Marc Chagall was a first-hand witness of the Bolshevik revolution that turned Russia upside down in 1917. The passing of a law that did away with all national and religious discrimination gave him, as a Jewish artist, the status of full Russian citizenship for the first time.

He then entered an ecstatic period of creativity, producing a series of monumental masterpieces.

Each of these large paintings seems like a hymn to the Chagalls' happiness, such as

"The Double Portrait with a Glass of Wine" of 1917,

and "Above the City" of 1918, showing the two lovers, Chagall and his wife Bella, flying off into the clouds, free as air. Everything exudes his euphoria at the time.

As the months went by, however, Chagall felt compelled to help young residents of Vitebsk lacking an artistic education, and to support other Jews from humble backgrounds, like himself. He then conceived the idea of creating a revolutionary art school in his city, open to everyone, free of charge and with no age restriction. His project, which also included the creation of a museum, was the perfect embodiment of Bolshevik values, and was approved in August 1918 by Anatoly Lunacharsky, head of the People's Commissariat for Education. A month later, he appointed Chagall as Fine Arts Commissioner, initially tasking him with organising the festivities for the first anniversary of the October Revolution.

Chagall invited all the artists of Vitebsk to make panels and flags based on preparatory drawings, several of which have survived. In his autobiography, "My Life", Chagall later wrote:

"All over the city my multicoloured beasts swayed in the air, swollen with revolution. The workers moved forward, singing the International. Seeing their smiles, I was sure they understood me. The Communist leaders didn't seem so happy. Why was the cow green? Why was the horse flying in the sky? Why? What did this have to do with Marx and Lenin?"

After the celebrations, the Commissioner poured his entire energy into creating his school, and it was officially inaugurated on 28 January 1919. Chagall, though admired by his students, had to struggle somewhat to get his establishment up and running.

The first teachers began to leave, like Ivan Puni; meanwhile others arrived, like Vera Ermolayeva, the future director, and most importantly, El Lissitzky, who took charge of the printing, graphic design and architecture workshops. He pushed his friend Chagall to bring in the leader of the abstract movement, Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprematism. It did not take long for this extraordinary, charismatic theorist to galvanise the young students after his arrival in November 1919. He rapidly formed a group with teachers who sympathised with the new movement: Unovis ("champions of new art"). One of their slogans was "Long live the Unovis party, which asserts new forms of Suprematist utilitarianism."

The collective began to design posters, magazines, streamers, signs and ration cards. Suprematism infiltrated every sphere of social life. Its members became involved in the presentation of festivities, and their work decorated trams, façades and speakers' rostrums. Colourful squares, circles and rectangles invaded the city's walls and streets.

Suprematist abstraction became the new paradigm of not only the school but the world in general. Lissitzky, as a trained architect, played a crucial role in all this. With his extraordinary Proun series (projects for asserting the new in art), he was the first to extend architectural volume to the pictorial plane of the Suprematists, considering the series as "stations where one changes from painting to architecture". Meanwhile, during his years in Vitebsk, Malevich began to abandon painting – an exception being his magisterial Suprematism of the Spirit – in favour of his main theoretical writings and education.

A methodical and stimulating teacher, he attracted ever more students, while Chagall found himself increasingly isolated. His dream was to develop a revolutionary art independent of style: the dual principle that had guided him in filling his museum and organising the first public exhibition in December 1919, where paintings by Vassily Kandinsky and Mikhail Larionov were seen alongside the abstract works of Olga Rozanova.

But this dream came to an end in the spring of 1920. With his classes slowly emptying of students, Chagall decided to leave Vitebsk in June and went to live in Moscow, where he worked for the Jewish theatre. Deeply upset by this setback, he held a grudge against Malevich, believing that he had plotted against him.

After Chagall's departure, Malevich and the Unovis collective, now in sole command, worked at "building a new world". Collective exhibitions were staged in Vitebsk and major Russian cities, and local committees

were set up all through the country, like the Unovis groups in Smolensk with Vladislav Streminsky and Katarzyna Kobro, Orenburg with Ivan Kudriashov, and Moscow with Gustav Klutsis and Sergei Senkin.

The latter were joined by Lissitzky, who became part of the new Constructivist movement in the winter of 1920. With the end of the civil war in 1921/1922, the political climate changed. The Soviet authorities decided to impose order in the ideological and social sphere, and this involved eliminating artistic movements that did not directly serve the interests of the Bolshevik party. In May 1922, the first batch of students graduating from the school was also the last. During the summer, Malevich left for Petrograd with several of his students, where he continued to develop his ideas on volumetric Suprematism, building models of Utopian architecture, called Architectones, and designing porcelain tableware. Over the years, Chagall's people's art school gradually became a revolutionary laboratory for rethinking the world.

The artists

Marc Chagall ; Ilya Chashnik ; Mstislav Dobuzhinsky ; Vera Ermolayeva ; Robert Falk ; German Fedorov ; Natalia S Gontcharova ; Hanna Kagan ; Wassily Kandinsky ; Lazar Khidekel ; Ivan Kliun ; Gustav Klucis ; Katarzyna Kobro ; Nina Kogan ; Ivan Kudriachov ; Moisei Kunin ; Mikhail Larionov ; El Lissitzky ; Evgenia Magaril ; Kazimir Malévich ; Yuri Pen ; Ivan Puni ; Alexander Romm ; Efim Royak ;Olga Rozanova ; Sergei Senkin ; David Shterenberg ; Vladislav Streminsky ; Nicolai Suetin ; Ivan Tilberg ; Boris Tsetlin ; Michail Wechsler ; David Yakerson ; Lev Yudin.

The latter were joined by Lissitzky, who became part of the new Constructivist movement in the winter of 1920. With the end of the civil war in 1921/1922, the political climate changed. The Soviet authorities decided to impose order in the ideological and social sphere, and this involved eliminating artistic movements that did not directly serve the interests of the Bolshevik party. In May 1922, the first batch of students graduating from the school was also the last. During the summer, Malevich left for Petrograd with several of his students, where he continued to develop his ideas on volumetric Suprematism, building models of Utopian architecture, called Architectones, and designing porcelain tableware. Over the years, Chagall's people's art school gradually became a revolutionary laboratory for rethinking the world.

The artists

Marc Chagall ; Ilya Chashnik ; Mstislav Dobuzhinsky ; Vera Ermolayeva ; Robert Falk ; German Fedorov ; Natalia S Gontcharova ; Hanna Kagan ; Wassily Kandinsky ; Lazar Khidekel ; Ivan Kliun ; Gustav Klucis ; Katarzyna Kobro ; Nina Kogan ; Ivan Kudriachov ; Moisei Kunin ; Mikhail Larionov ; El Lissitzky ; Evgenia Magaril ; Kazimir Malévich ; Yuri Pen ; Ivan Puni ; Alexander Romm ; Efim Royak ;Olga Rozanova ; Sergei Senkin ; David Shterenberg ; Vladislav Streminsky ; Nicolai Suetin ; Ivan Tilberg ; Boris Tsetlin ; Michail Wechsler ; David Yakerson ; Lev Yudin.