National Gallery

7 October 2019 – 26 January 2020

The first-ever exhibition devoted to the portraits of

Paul Gauguin will open at the National Gallery in October 2019.

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits

(7 October 2019 – 26 January 2020) will show how the French artist,

famous for his paintings of French Polynesia, revolutionised the

portrait.

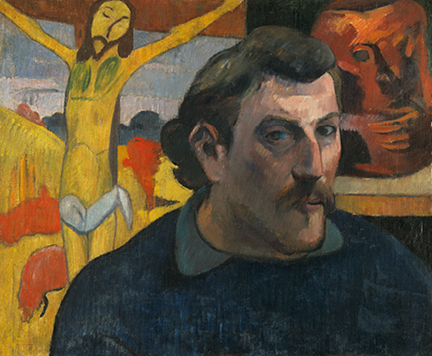

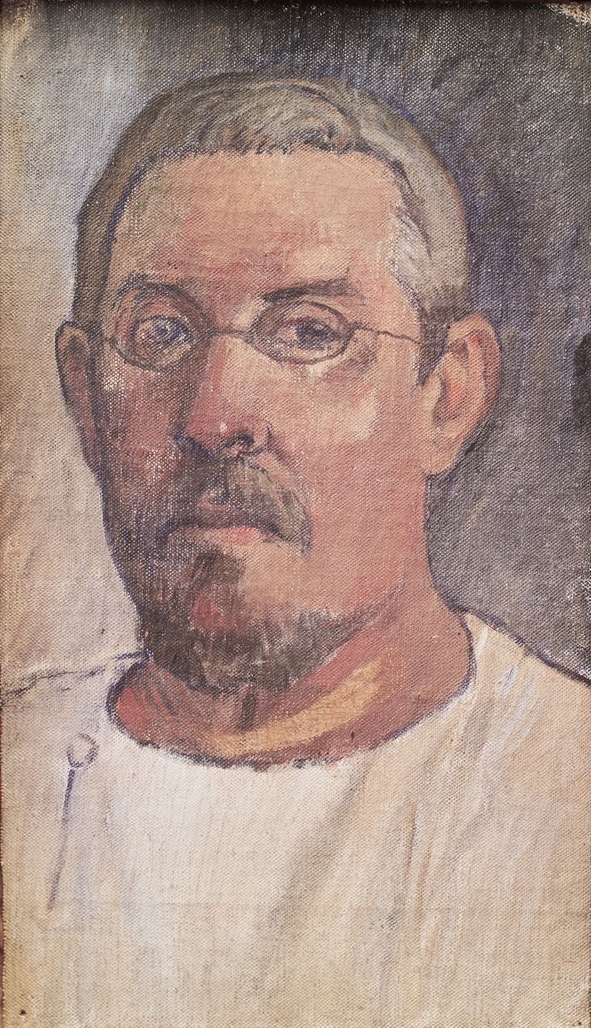

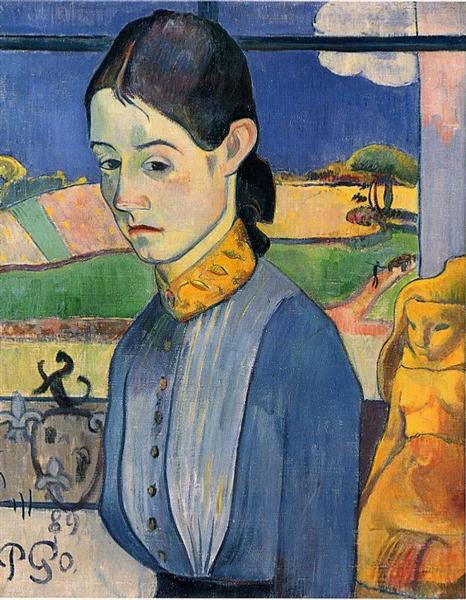

Paul Gauguin, 'Self

Portrait with Yellow Christ', 1890-1, Musée d'Orsay, Paris (RF 1994-2) ©

RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / René-Gabriel Ojéda

This landmark exhibition of major loans from museums and private

collections throughout the world will show how Gauguin used portraits

primarily to express himself and his ideas about art.

Although he was fully aware of the Western portrait tradition,

Gauguin was rarely interested in exploring his sitters’ social standing,

personality, or family background, which had been among the main

reasons for making portraits in the past.

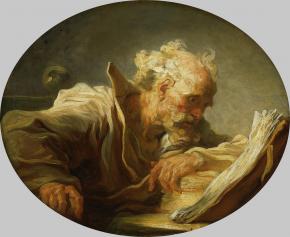

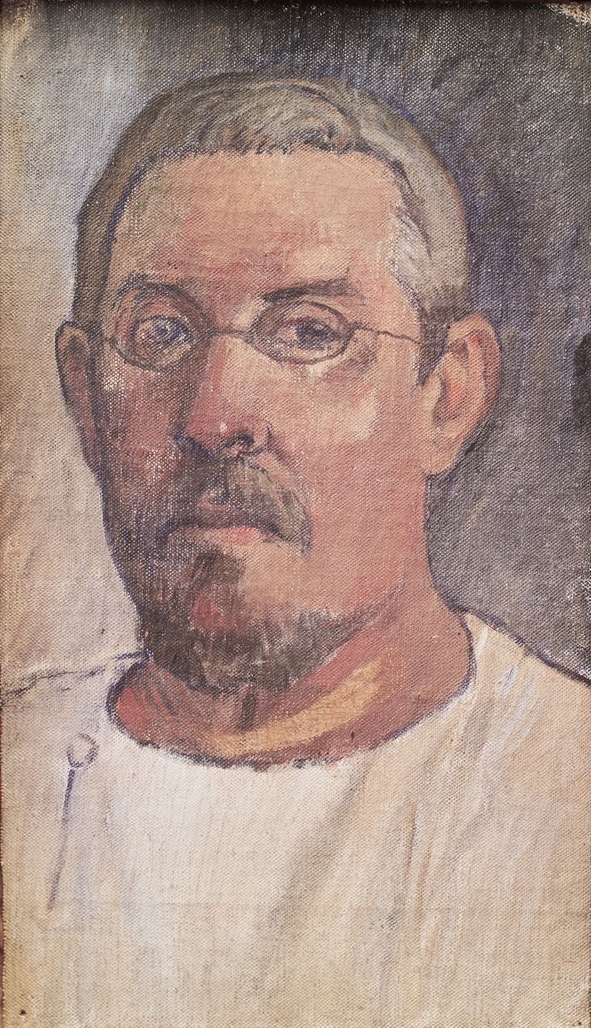

Paul

Gauguin, Portrait of the Painter Slewinski, 1891. Oil on canvas, 53.5 ×

81.5 cm. National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo. Matsukata Collection ©

National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo.

From sculptures in ceramics and wood to paintings and drawings, an

extraordinary range of media for a National Gallery exhibition, visitors

will see how Gauguin interpreted a specific sitter or model over time,

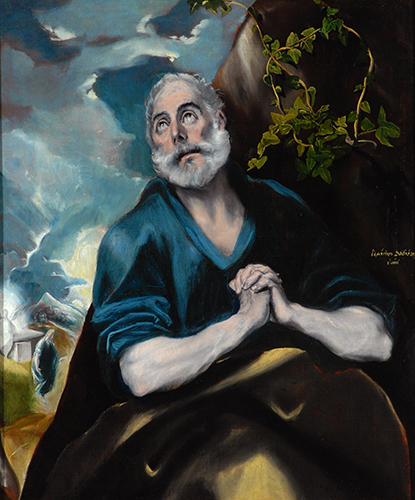

and often in different guises. A group of self portraits in the

exhibition, for example, will show how Gauguin created a range of

personifications including his self-image as Jesus Christ. Together with

his use of intense colour and his interest in non-Western subject

matter, his approach had a far-reaching influence on artists throughout

the late 19th and 20th centuries including

Henri Matisse and

Pablo Picasso.

'The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits' will show how the

artist – inspired by his time spent in Brittany and French Polynesia

from the mid-1880s to the end of his life in 1903 – became fascinated by

societies that to him seemed close to nature. With their folk tale

heritage and spirituality, these communities appeared to him to be far

removed from the industrialisation of Paris.

Gauguin’s inspiration to visit French Polynesia was partly drawn from

the exotic novels of Pierre Loti (whose naval training included a stay

in Tahiti), his photographs of Borobudur sculptures, and Pacific

exhibits he had seen at Paris’s Exposition Universelle in 1889. At the

same time his own upbringing in Peru allowed him to think of himself as

someone who stood outside the European tradition, a ‘savage,’ while the

European artistic and literary circles in which he moved also helped

shape his views towards Tahiti and the Marquesas.

Gauguin’s life and art have increasingly come under scrutiny,

especially the period he spent in South Polynesia. The Gallery aims to

explore this controversial subject matter in the exhibition

interpretation and accompanying programme and to join conversations now

taking place that consider Gauguin's relationships and the impact of

colonialism through the prisms of contemporary debate.

Featuring over fifty works, the exhibition includes paintings,

sculptures, prints, and drawings many of which have rarely been seen

together. These include works from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France; The

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA; The Art Institute of

Chicago, USA.; The National Gallery of Canada; The National Museum of

Western Art, Tokyo, Japan; and The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of

Belgium.

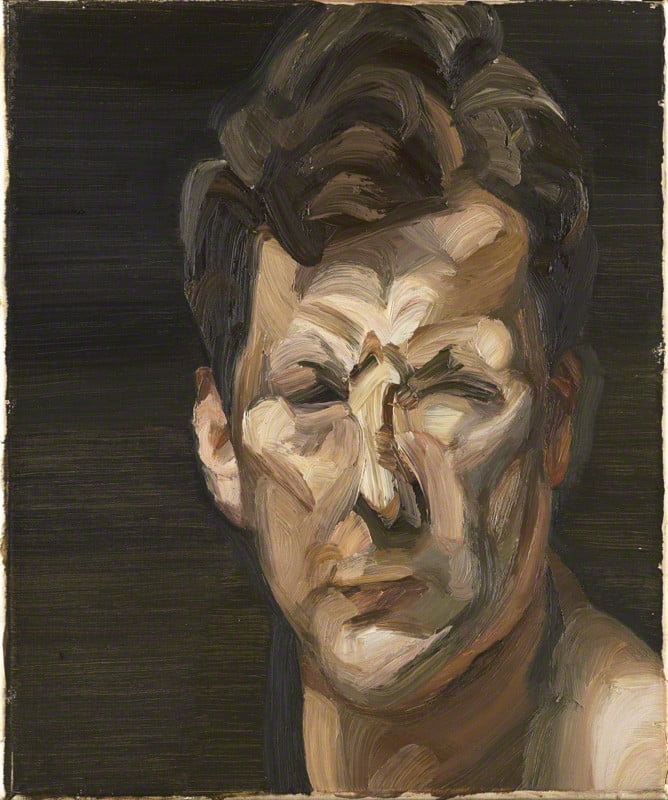

With pictures from his early years as an artist through to his final

visit to the South Seas, the first room of the exhibition will be

dedicated to self portraits; the most numerous of all Gauguin’s

paintings. By making himself his chief subject and by assuming different

personalities these images show Gauguin constantly reinventing himself.

Included in this room is a rough, grotesque self-portrait head with his

thumb in his mouth demonstrating his interest in non-Western

iconography and art, and also his radical experimentation in different

media ('Anthropomorphic pot', enamelled sandstone, 1889, Musée d'Orsay,

Paris).

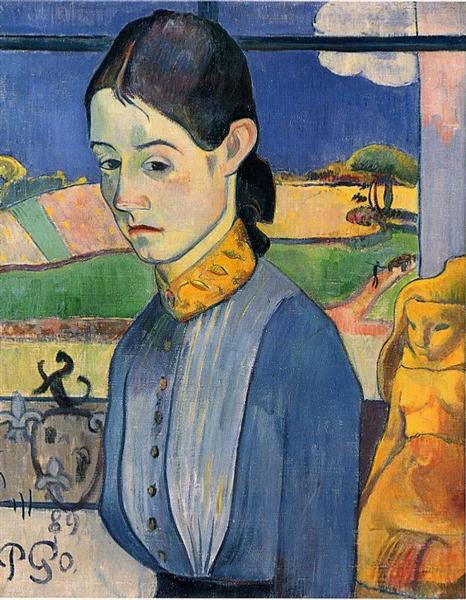

Room 2 is devoted to the period he spent in Brittany (1884–-91)

where, in the remote village of Le Pouldu, he turned his back on his

life as a Paris stockbroker to become the leading figure of a new

artists’ colony. This room also contains portraits of some of the

friends he had made in Paris and members of his family including

'Mette

in Evening Dress', 1884 (The National Museum of Art, Architecture, and

Design, Oslo).

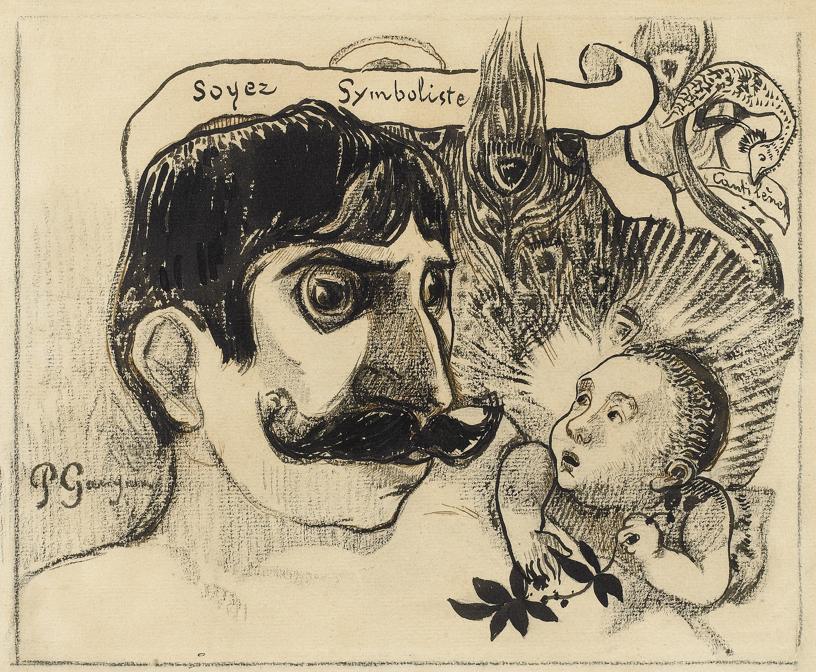

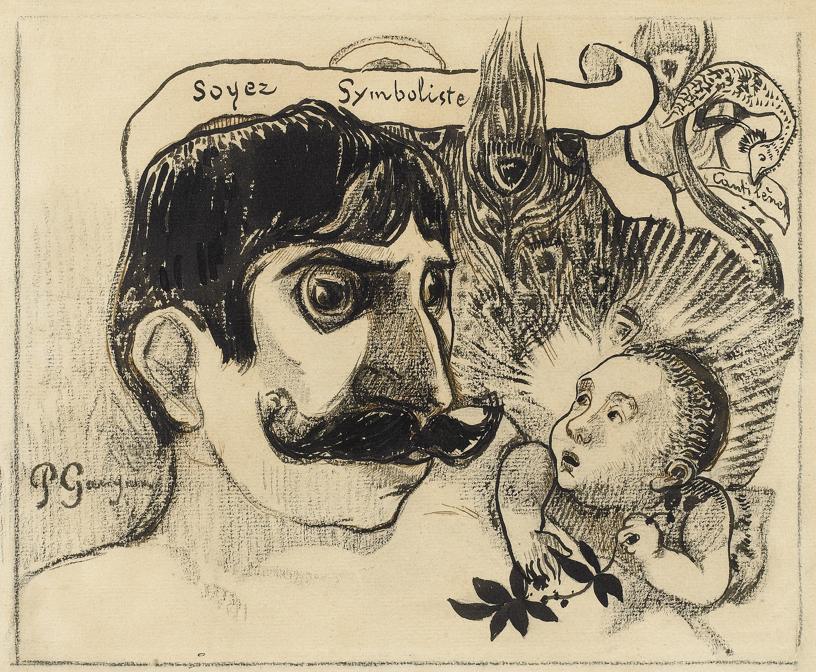

In paintings such as 'Be Symbolist: Portrait of Jean

Moréas' (1890–1, Talabardon & Gautier, Paris)

and 'Young Breton

Woman', (1889, Private Collection) Gauguin started to push the

boundaries of portraiture by eschewing its usual conventions of

resemblance, flattery, and coherence of time and space.

Gauguin’s fraught relationships with fellow artists are explored in

Room 3, particularly two key friends who, in spite of falling out with

him, remained as portrait subjects for the rest of his life:

Vincent van Gogh

and Meijer de Haan (1852–1895). A group of portraits of de Haan shows

how he became a symbolic cipher within his work that far outlived their

friendship (and the sitter himself), stretching the possibilities for

portraiture into something new across different media, such as the

wooden bust of de Haan (1889–90, National Gallery of Canada).

Room 4 covers Gauguin’s first Tahitian trip (1891–3) where he sought

an escape from ‘civilisation’ yet always with an eye to France, and how

he was trying and failing to break into the Parisian art market from a

distance. As well as including paintings of Teha’amana a Tahura, this

room also tracks his continued experiments in different media, which

made direct reference to the indigenous objects now surrounding him, in

works such as 'Tehura (Teha’amana)' in wood, (1891–3, Musée d'Orsay,

Paris);

and 'Arii Matamoe (The Royal End)', (1892, The J. Paul Getty

Museum, Los Angeles).

Featuring his return to Paris and Brittany and his second stay in

Tahiti (1893–5), Room 5 will also include works containing distinctly

Tahitian imagery. In a portrait made in Brittany, a young Breton woman

in prayer is shown wearing a Tahitian missionary dress

('Young Christian

Girl', 1894, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown,

Massachusetts, USA);

while in '

Self Portrait with Manao Tupapau',

(1893–4, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) can be seen the painting

'Manao Tupapau

(The Spirit of the Dead Watching)', the print of which will also be on

display (1894, National Gallery of Canada).

Room 6 has a selection of portraits in which Gauguin used symbolic

objects, arranged into still lifes, to stand in for absent figures.

These surrogate portraits had been part of Gauguin’s repertoire from the

1880s, but this room shows how they took on increasing significance

during the isolation of his later years. They include proxy portraits of

Van Gogh, his former friend who had been dead for a decade, which

depict the blooms from sunflower seeds sent from France (such as 'Still

Life with ‘Hope’', 1901, Private collection, Milano, Italy); Gauguin may

have been the first to understand that sunflowers were Van Gogh’s

signature motif and he would be famous for them.

The final room of the exhibition will be devoted to Gauguin’s late

portraits. Despite a recurring illness and a decline in the quantity of

his output, the portrait remained essential to Gauguin’s art in his

final years on the Marquesan Island of Hiva Ooa. His use of portraits to

express his role in local politics is reflected in the form of the

wooden carved sculpture made for the home he built himself caricaturing

the local bishop, as a lecherous devil (Père Paillard, 1902, National

Gallery of Art, Washington, DC).

His last self portrait, perhaps the

simplest and most direct of all, probably made shortly before the end of

his life, aged 55, brings the exhibition to a close

(Self Portrait,

1903, Kunstmuseum Basel).

Christopher Riopelle, The Neil Westreich Curator of Post-1800

Paintings at the National Gallery, and co-curator of 'The Credit Suisse

Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits', says:

'Gauguin radically expanded the parameters of portraiture.

He understood how deeply modern art would be the expression of the

individual, idiosyncratic personality, and he realised that the portrait

must serve as the portal to rich, contradictory interior worlds. That

he found the stylistic vocabulary to evoke this complexity is the mark

of his genius.'

Dr Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery, says:

“This is the first time that an exhibition focuses on

portraits by Gauguin. Never a conventional portrait painter, his

radical, highly personal vision led to the creation of a group of works

that are striking, moving and at times disturbing. Through paintings,

prints, sculptures and ceramics the exhibition explores how he defined

his own persona in his self -portraits and how he fashioned the images

of friends, lovers, and associates.”

David Mathers, CEO of Credit Suisse International, says:

“We are delighted to be supporting 'The Credit Suisse

Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits' at the National Gallery, London. This

exhibition proposes a new approach to Gauguin by looking, for the first

time, specifically at portraits inspired by those he knew intimately in

the later years of his life. His posthumous fame demonstrates the

lasting impression left on modern art by this enigmatic and talented

figure. Gauguin’s unique relationship with Vincent van Gogh and his

contribution to Symbolism during the turn of the 20th century make this a

fascinating foray into his artistic production.”

'The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits' is organised by the

National Gallery and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

The exhibition is curated by Cornelia Homburg and Christopher

Riopelle from an initial concept by Cornelia Homburg. Cornelia Homburg

is the guest curator for the National Gallery of Canada, and Christopher

Riopelle is the Neil Westreich Curator of Post-1800 Paintings at the

National Gallery, London.