Albuquerque Museum opens June 26, 2021

Philbrook Museum of Art, from October 17, 2021 to February 20, 2022

Artis—Naples, The Baker Museum, from March 26 to July 24, 2022

Crocker Art Museum from August 28 to November 20, 2022

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, from December 18, 2022 to April 16, 2023

The major traveling exhibition Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group kicks off this summer.

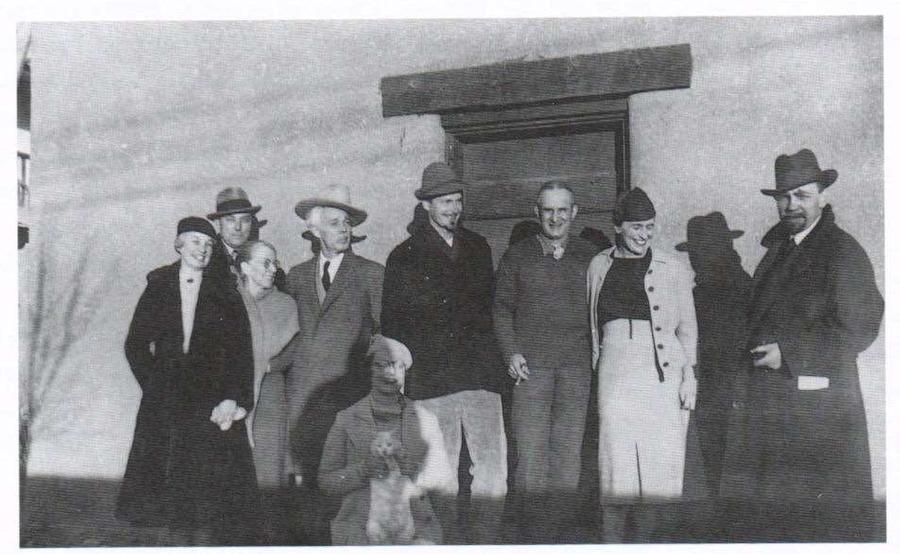

This landmark museum exhibition—the first exhibition of this important group of American modernists to be shown beyond New Mexico’s borders, and the first to be accompanied by a major scholarly publication—is devoted to an often overlooked group of 20th century abstract artists who pursued enlightenment and spiritual illumination. Organized by independent curator Michael Duncan and the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, Calif., this survey of 85 works made by the 11 visionary abstractionists is drawn from a variety of private and public collections including the Crocker’s. It aims to provide a broad perspective on the group’s work and reposition it within the history of modern painting and 20th century American art. The groundbreaking show will be accompanied by a fully illustrated publication by Duncan and other scholars, including the Crocker’s Associate Director and Chief Curator Scott A. Shields, who assert the group’s artists as crucial contributors to an alternative through line in modern art history, one with renewed relevance today. The traveling exhibition opens at the Albuquerque Museum on June 26, 2021, and then travels to four additional venues (see schedule at end).

“These motivated individuals transformed the dramatic natural surroundings of the Southwest into luminous reflections of the human spirit,” says Shields, a leading specialist in the art of California and the American West. “This sets their work apart from abstraction made in Europe at the same time—that and the otherworldly beauty and quality of the artwork itself. Well connected, well read, but isolated geographically, the artists sought to connect and communicate with viewers through potently charged symbols and dynamic relationships of color and form.”

“Despite the quality of their works, this group of Southwest artists have been neglected in most surveys of American art, their paintings rarely exhibited outside of New Mexico,” said Duncan, who originally planned the exhibition nearly a decade ago. A corresponding editor for Art in America whose writings have focused on maverick artists of the 20th century and West Coast modernism, he asserts that “as we settle into the 21st century, the ‘spiritual’ seems no longer a complete taboo, and art history is undergoing a vast sea change.”

The Transcendental Painting Group achieved their modernity through potently charged shapes, patterns, and archetypes that they believed dwelled in the “collective unconscious.” The artists looked to a wide variety of literary, religious, and philosophical forces, including Zen Buddhism, Theosophy, Agni Yoga, Carl Jung, and Friedrich Nietzsche, and were greatly impacted by the Russian-born artist and theoretician Wassily Kandinsky. Convinced that an art capable of being intuitively understood would have equal validity to representational painting in an era of uncertainty, political divide, and fear, they attempted to promote abstraction that pursued enlightenment and spiritual illumination. Their manifesto stated their purpose: “To carry painting beyond the appearance of the physical world, through new concepts of space, color, light and design, to imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual.”

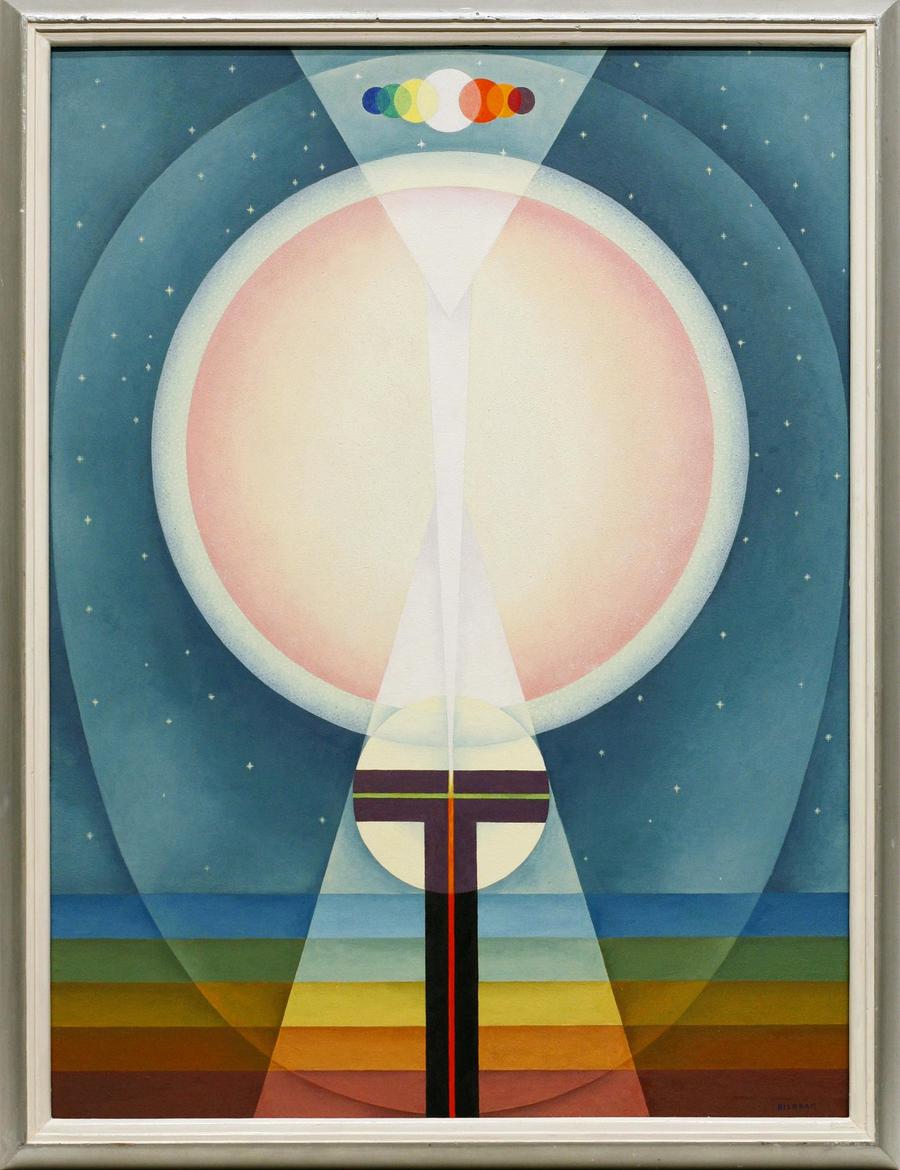

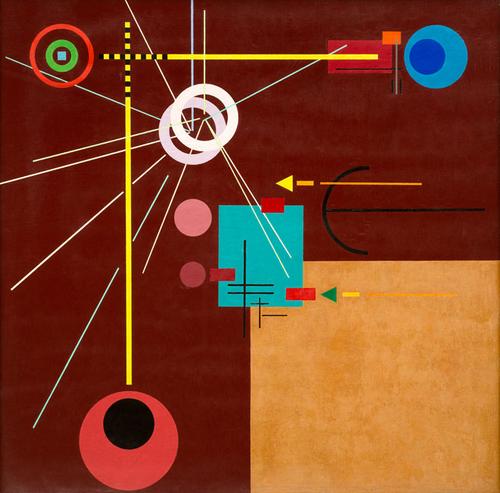

The group was co-founded by New Mexico painters Raymond Jonson (1891–1982), today a vastly underrated figure in the development of abstraction in the United States who generally pursued a rigorous clarity in his art and was the stalwart backbone of the group, and Emil Bisttram (1895–1976), a key Southwest modernist, whose work evidenced a calculated precision that demonstrated his interest in the theory of Dynamic Symmetry and geometry’s potential for occult symbolism.

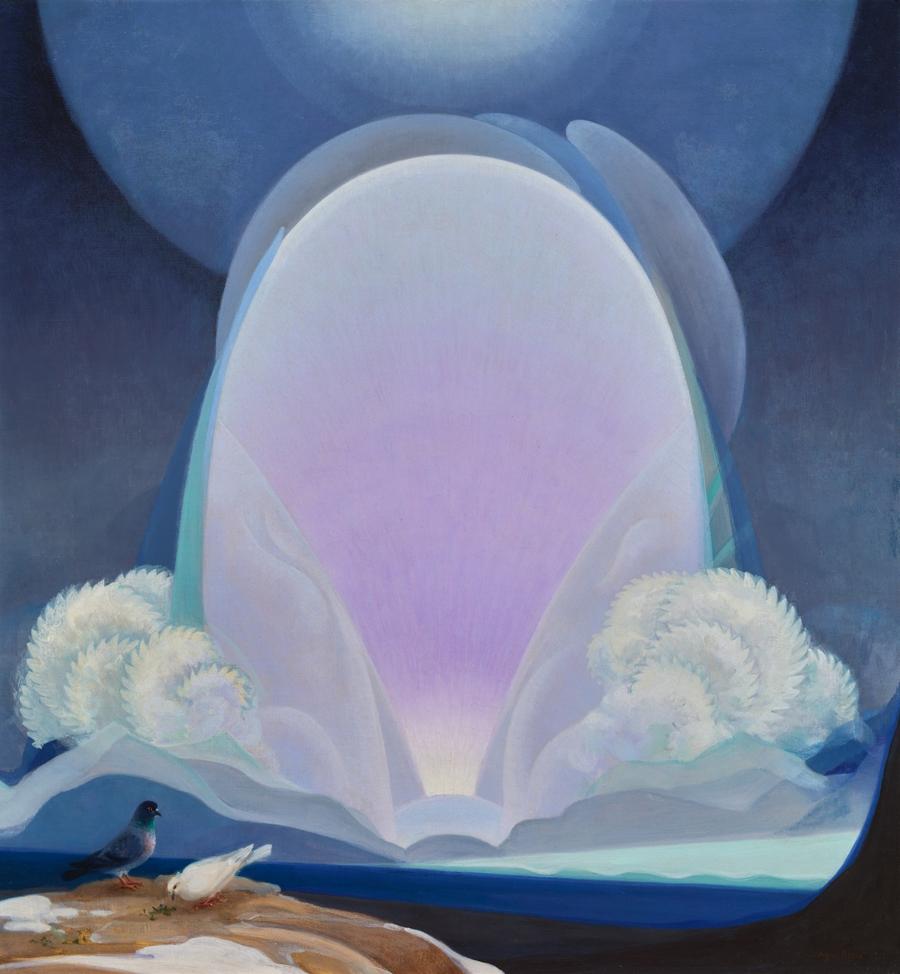

All of the artists in the TPG sought to imbue their art with unforgettable, affecting metaphors, symbols, and visions, employing the freewheeling imagery of Surrealism to depict a transfigured, spiritually alive America. Agnes Pelton (1881–1961), increasingly appreciated today for her shimmering, celestial forms, was the honorary president of the group and its educational arm, the American Foundation for Transcendental Painting. Lawren Harris (1885–1970), of Canada, was the group’s only non-American member and known primarily for his light-filled, sharply delineated mountain landscapes. Florence Miller Pierce (1918–2007), the youngest member, created stunning paintings and drawings using geometric and biomorphic forms. Horace Pierce (1916–1958), who created graph-like and spiraling geometries in space, was also an experimental filmmaker.

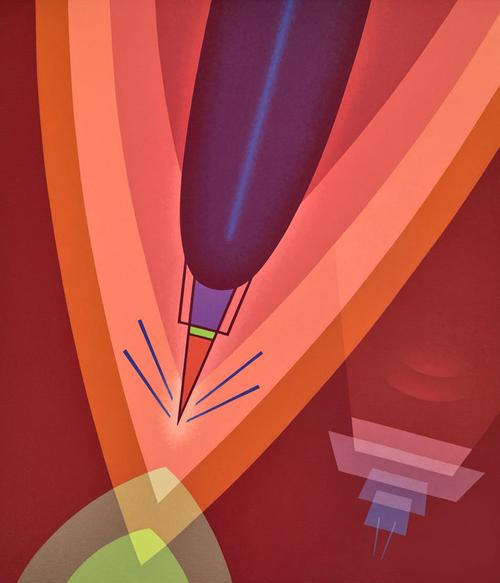

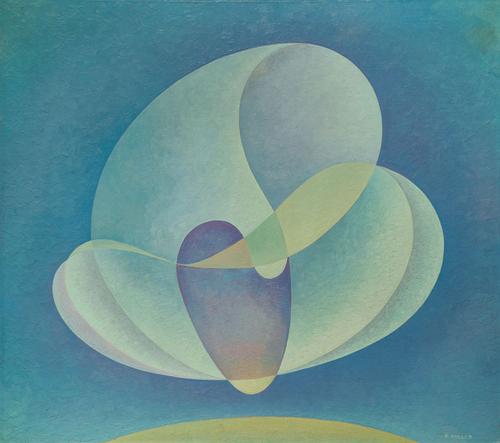

Robert Gribbroek (1906–1971) was a fine artist, commercial art director, and layout artist for Hollywood animation studios; William Lumpkins (1909–2000), the only New Mexico native of the group, produced expressive watercolors that were the most unrefined and expressionistic, his style manifesting his interest in Zen Buddhism and Eastern thought; Stuart Walker’s (1904–1940) layered, swooping pastel forms embody transformative movement, growth, and enlightenment (pictured); and Ed Garman (1914–2004) was an idealist who took an improvisatory but analytical approach to his abstract compositions.

Also included in the survey are paintings by Dane Rudhyar (1895–1985), a philosopher, composer, artist, poet, novelist, and astrologer. Though not an official TPG member, his writings were critical in the group’s formation and cohesion.

The show includes striking, sublime works such as Oversoul (circa 1941), a warm, lyrical oil by Bisttram; Pelton’s stylized, shimmering Birthday (1943), that depicts the hallucinatory aura of the desert sky and landscape; and an ethereal, sensuous 1938 canvas by Walker invoking an idealized landscape of hills and clouds.

The exhibition is the sum of an astonishing array of loans and includes works drawn from the Crocker’s permanent collection including Winter (1933), a radiant, vibrant painting by Pelton, who sometimes incorporated representational elements that she felt could assist on the path to inner awareness and whose masterful and delicate abstractions have since the 1990s been rediscovered. The Crocker has also contributed two paintings by Jonson, a critical figure in expanding Southwest art beyond landscape painting and regional depictions to incorporate the light, color, and spirit of New Mexico in rich, metaphorical abstraction. These works, both from the early 1940s, demonstrate his interest in mechanical forms. Jonson, Duncan points out, himself became a strong advocate of Pelton’s work, praising her work for its luminosity.

“Another World” is accompanied by a lavishly illustrated exhibition catalogue (Delmonico Books, 2021). Revelatory, in-depth essays by Duncan; Shields; art historian, author, and independent curator Malin Wilson Powell; Catherine Whitney, a curator with a specialization in the regional Taos and Santa Fe painters; and Ilene Susan Fort, Curator Emerita at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; comprise the most significant contribution to the study and understanding of the group to date. The texts range from an exploration of the group in light of their international artistic peers, to their involvement with esoteric thought and Theosophy, their sources in the culture and landscape of the American Southwest, and the experience of its two female members. The handsome, colorful volume features stand-alone essays on each member, an illustrated chronology of the group with archival photography and ephemera, and an extended excerpt from Rudhyar’s polemical unpublished 1938 treatise positioning Transcendental art as a redemptive 20th century movement.

In the opening essay, “Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group,” Duncan asserts the group as contributors to an alternative approach to abstraction and places their art within the history of modern painting and 20th century American art. While Shields, in his “The Transcendental Painting Group and Significant Abstraction,” argues that while their art very often shares formal resemblances to that of modernist pioneers like Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O’Keeffe, “it was not the lack of an objective stimulus that set their work apart from that of their predecessors but a difference in motivation,” and that the group’s 19th century definition of Transcendentalism “gave way to the idea that art should be focused on the relationship between the maker’s inner self and the divine, rather than nature and the divine.”