At the Discover Portsmouth Welcome Center (Portsmouth Historical Society) in New Hampshire this summer is a special exhibition on two underappreciated American Impressionists.

“Twilight of American Impressionism: Alice Ruggles Sohier and Frederick A. Bosley” (through Sept. 12, 2021) showcases the largely unsung talents of Alice Ruggles Sohier and Frederick A. Bosley, two American impressionists working at a time when realistic art was falling out of fashion and abstract art was in vogue.

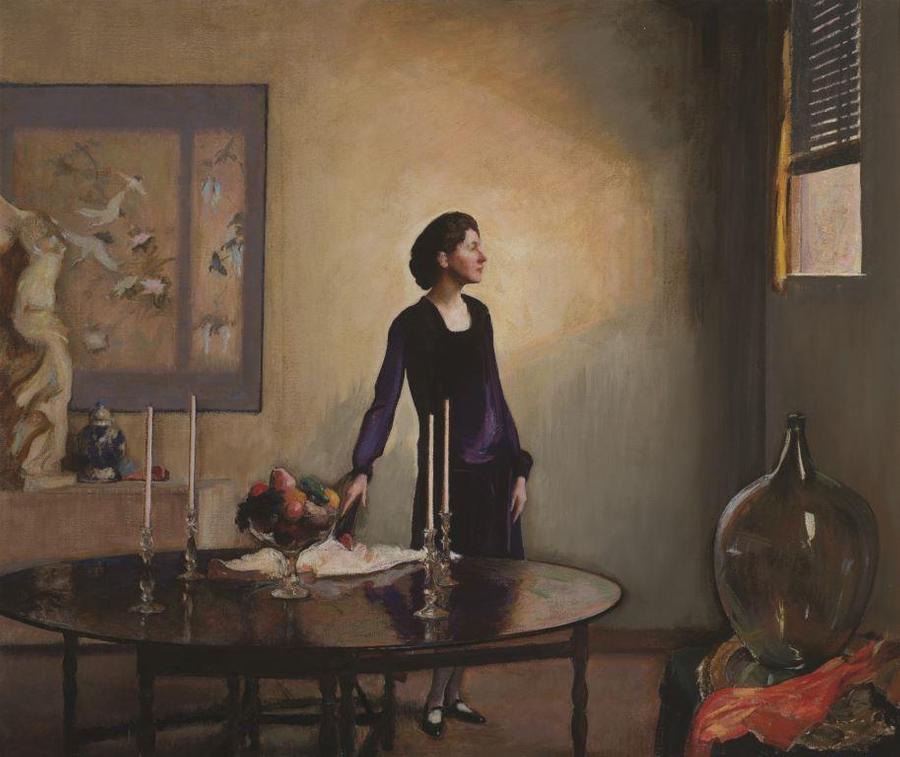

Alice Ruggles Sohier (1880–1969) and Frederick Andrew Bosley (1881–1942) were students of Edmund Tarbell, trained at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Related by marriage (Frederick was Alice’s brother-in-law), each artist became a master of the so-called Boston School, creating landscapes, interiors, still lifes, portraits, and other refined and elegant works notable for their sublime treatment of light and shade in the grand manner espoused by Tarbell and his disciples. Today, however, as was the case with Gertrude Fiske, Sohier and Bosley’s work is not particularly well known, nor have these important and intriguing artists received the scholarly attention that they deserve. This exhibition attempts to address this situation by bringing to light many of their major works that have slumbered for nearly a century and through enriching the biographical record of their lives.

Each artist faced challenges common to Boston School artists as they pursued a traditional career in an art world that was shifting dramatically to more modern modes as the twentieth century progressed. Sohier and Bosley, after enjoying the relative prosperity of the 1910s and 1920s, also had to cope with the effects of the Great Depression in the 1930s. Each also confronted individual obstacles. Alice had to navigate her career and family through a world dominated by men, and Frederick suffered from bouts of depression, especially after his resignation as director of the Museum School in 1931, a decision triggered by the institution’s shift to modernism.

As with the Fiske and Tarbell shows, the Sohier/Bosley exhibition will draw heavily on privately owned works that have rarely been exhibited publicly. Many of the works remain in the families of the artists’ descendants. Those same families also retain some of the furniture and small objects used as props in the paintings, as well as significant caches of period photographs and important documents.

These rich materials allowed us, to an unprecedented extent, to trace the trajectory of each artist’s career, as well as to provide an overview of their respective oeuvre. The result is a greater understanding of these individual overlooked artists and their place in the evolution of the Boston School. Twilight’s twenty-first-century perspective on the work of Sohier and Bosley shows that, while they may have been painting at the end of an era, they were at the height of their art.

In total, the exhibition contains about 65 major works with an additional number of studies, drawings, and associated objects, documents, and photographs.

The show will be accompanied by a catalogue published by the Portsmouth Marine Society Press, the publishing arm of the Society. This richly illustrated volume will include an essay by guest curator William Brewster Jr. Brewster, a grandson of Bosley and great-nephew of Sohier, is the author of the only previously published work devoted solely to the two artists, a pamphlet published in 2000 by the Portsmouth Athenaeum to accompany a small show of their work. A catalogue section will illustrate the individual works. The book also will include a bibliography.

Alice Ruggles Sohier, from a venerable Massachusetts family, received her art education in the Art Students League in Buffalo, New York, and then at the Museum School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from which she graduated in 1907. During her academic career, she studied with Tarbell and Frank W. Benson, and received many awards and honors. Upon graduation she was the recipient of a prestigious Paige Traveling Scholarship, which provided funds for two years of travel and study in Europe. Upon her return, she exhibited widely from 1910 to 1930, being represented in at least twenty-nine shows throughout the country and receiving a bronze medal at the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915. Her work was noted for its realism and treatment of light in the Tarbell manner. Throughout her career, Sohier faced the challenges common to female artists at the time, including balancing career and family. She married Louis Sohier, an engineer, in 1913. (Louis Sohier’s sister Emily was married to Frederick Bosley.) The Sohiers moved to Pennsylvania and, later, to Concord, Massachusetts. Although Sohier stopped exhibiting ca. 1930, she continued to paint until at least 1959.

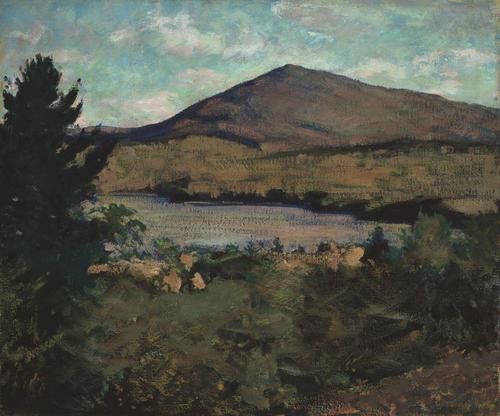

Frederick Andrew Bosley was born in Lebanon, New Hampshire. After high school, he too attended the Museum School, finishing the seven-year program in only six years. Like Sohier, he studied with Tarbell and Benson and won a Paige scholarship. In 1913, he succeeded Tarbell as the director of the Department of Drawing and Painting and as instructor in Advanced Painting, influential teaching positions he held until 1931. Bosley was known for his portraits, interiors, and landscapes, as well as for his abilities in pencil and charcoal drawing, and his prize-winning work was also widely exhibited. In the 1920s, he painted at the art colony in Peterborough, N.H., and he also attempted to open his own art school in Piermont. In 1930, the Museum School shifted its focus away from traditional representational painting to a more modern approach. Bosley, along with several other faculty members, resigned in protest the next year. He suffered from depression for the next decade and passed away in 1942.