In the final event of a year that has paid tribute to Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza (1921-2002), marking the 00th anniversary of his birth, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza is presenting an exhibition which brings together the magnificent collection of American art assembled by the Baron over more than three decades. The works on display come from both the Thyssen family and the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza collections, as well as and principally from the museum itself, which has an exceptional holding of this school in a European context, making the Museo Thyssen in Madrid a key point of reference for knowledge of American art.

American Art from the Thyssen Collection is the result of a research project undertaken with the support of the Terra Foundation for American Art to study and reinterpret these paintings with a new thematic and transversal approach through categories such as history, politics, science, the environment and urban life. It has also taken into account issues including gender, ethnicity, social class and landscape in order to provide a more profound knowledge of the complexities of American art and culture.

This reinterpretation is revealed in the new presentation of the works in the galleries and in the corresponding catalogue with essays by the two curators: Paloma Alarcó, Head of the Department of Modern Painting at the museum, and Alba Campo Rosillo, Terra Foundation Fellow of American Art, who have also written the texts that accompany each thematic section, together with the museum’s curators of modern painting, Clara Marcellán and Marta Ruiz del Árbol. This selection of works also benefits from commentaries by the experts on American art who have participated in the project. As with all the exhibition and activities associated with the centenary of Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza, the exhibition has received the support of the Comunidad de Madrid.

The 140 paintings brought together for this event are displayed in Rooms 55 to 46 of the museum’s first floor, organised into four thematic sections: Nature, Culture Crossings, Urban Space and Material Culture, which are in turn divided into various sub-sections that establish dialogues between paintings from different periods and by different artists, combining 19th- and 20th-century art.

1. NATURE

The exhibition’s opening section is devoted to landscape, a central theme in the Thyssen collection in general and in American art in particular. The concept of nature was essential to the creation of the young North American nation and the emergence and evolution of the genre of landscape can thus not be dissociated from American history and the country’s political consciousness. Landscape painting defined the country while at the same time representing it, and the reflection of a virgin nature was consequently established as the ideal formula for reaffirming the growing national spirit.

Sublime America

Following the country’s independence in 1776 and above all at the start of the 19th century American artists, most of whom had trained in Europe, became aware of the grandeur of the country’s topography. In its early years American landscape painting was an adaptation of the European Romantic tradition to the exuberance of the New World, combined with a religious and patriotic sentiment. The section Sublime America focuses on nature as a source of spirituality and pride, of connectivity, life and death. This is evident in the work of Thomas Cole, the first painter to reveal the relationship between man and nature through his use of the conventions of the Romantic sublime and to visually express a religious sentiment; in the work of Frederic Church, who contributed the scientific spirit characteristic of his activities as an explorer; and of George Inness, whose visionary and poetic work aims to arouse the viewer’s emotions.

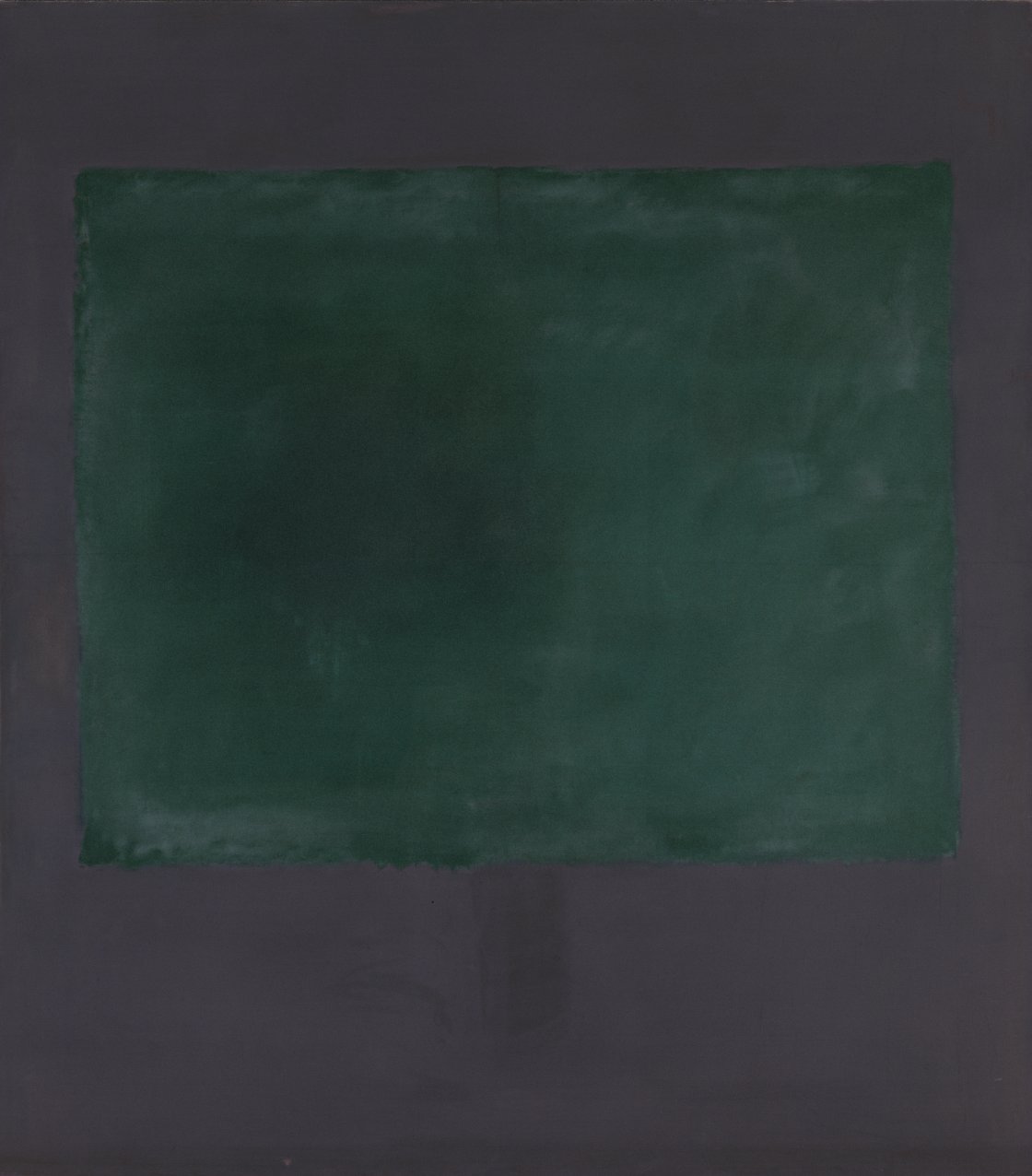

However, the influence of transcendental Romanticism goes beyond any chronological framework, making it possible to associate 19th- and 20th-century works. The allegory of the cross seen in paintings by Cole and Church is still present in the output of some of the Abstract Expressionists such as Alfonso Ossorio and Willem de Kooning, while the artists associated with the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, reintroduced the American landscape’s mystical past into modern art. Other 20th-century painters such as Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still remained in contact with sublime nature through abstraction.

Earth Rhythms

In the mid-19th century the positivist, post-Darwinian outlook encouraged a growing scientific interest in the natural world. This second generation of landscape painters came close to the naturalist trend that prevailed in Europe for much of the 19th century, focusing on natural history and on nature’s constant state of transformation. Asher B. Durand, a follower of Cole and a fervent defender of plein air painting, reveals a meticulously scientific realism in his work, as do John Frederick Kensett and James McDougal Hart.

Following a lengthy trip to Europe where he studied the new treatises on light and colour, Frederic Church started to reveal an interest in depicting the transformation of the landscape over the seasons and in different atmospheric conditions, as did Jasper Francis Cropsey who introduced the use of the panoramic format which became widespread among American artists around the mid-century. Slightly later, artists such as Theodore Robinson and William Merritt Chase reveal the incipient influence of the fleeting quality of French Impressionism.

Moving into the 20th century, a notable figure is Arthur Dove who focused on the transformation of the earth’s internal forces and on changing atmospheric conditions, aiming to integrate nature and abstraction in his painting. Another key name is Hans Hofmann, for whom “nature is always the source of the artist’s creative impulses” and who employed a type of organic figuration which combined his European roots and training with innovations arising from his American experience. Jackson Pollock also expressed his desire to reproduce the rhythms of nature; the choreography of the artist moving his body and his hand over the canvas on the floor was a true liturgy linked to the natural world.

Human impact

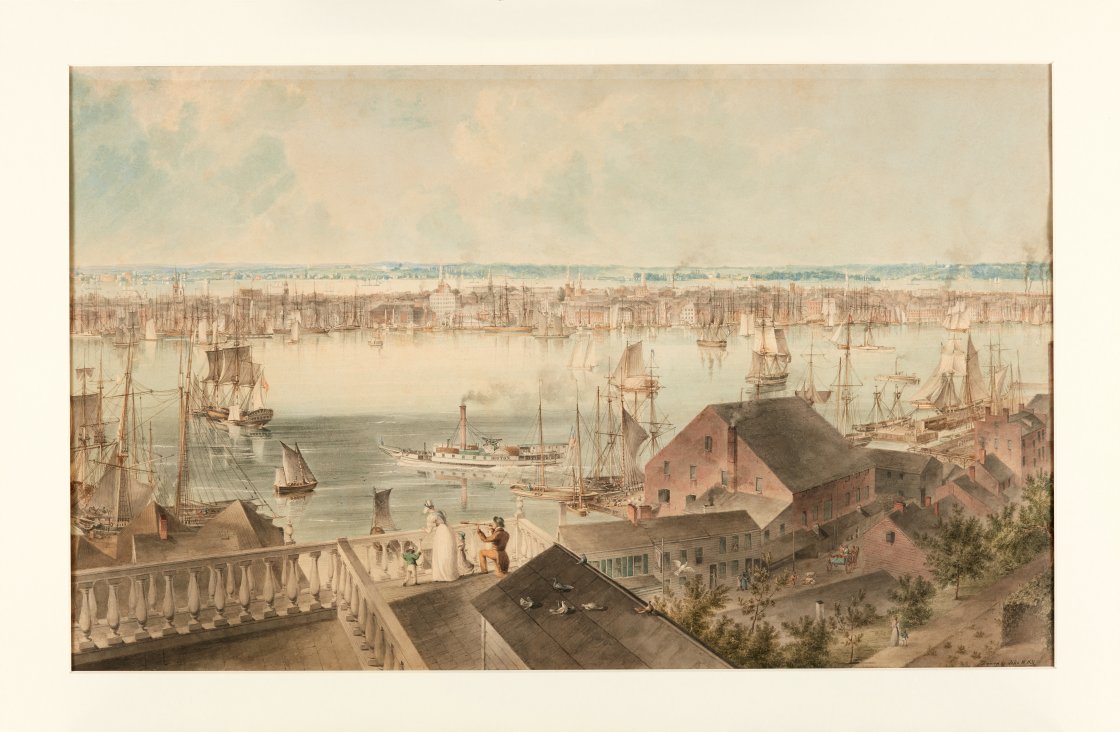

The tension between civilisation and the preservation of nature penetrated 19th-century painting to such an extent that it laid the way for our modern environmental awareness. Most of the early American landscape painters moved to live in the countryside and frequently depicted scenes of bucolic life which symbolise the abundance of the earth and the harmony between the early settlers and the natural setting. Others became interested in exploring the passing of time through human activity, as evident in scenes of ports on the Atlantic coast by John William Hill, Robert Salmon, Fitz Henry Lane, Francis A. Silva and John Frederick Peto, which find their counterpoint in Charles Sheeler’s 20th-century vision in Wind, Sea and Sail.

The legacy of the tradition of landscape painting was inherited in the late 19th century by Winslow Homer whose work reflects the confrontation of man and the forces of nature. It continues in the 20th century with Edward Hopper; the image of the dead tree that reappears in some of his works connects to those present in paintings by Cole and Durand, uprooted by destructive human impact.

2. CULTURE CROSSINGS

With a title that refers to moments of contact between different communities, this section is organised into three sub-sections:

Settings

Settings focuses on the representation of the natural landscape as the space in which the complex history of North America has been written. From the mid-18th to the 20th century numerous paintings depict narratives that present the land as the site of colonial assimilation, exalting the Euro-American presence over the indigenous or Afro-American one. Landscape also functions as the setting for accounts of man’s domestication of untamed territories and of the inevitably of the extinction of the Native Americans. Examples include the work of Charles Wilson Peale in his portrait of the children of a rich colonist on his plantation of peaches in Maryland; that of Charles Wimar in his depiction of the indigenous people as resigned to their extinction in the face of colonial advance; and the appropriation of indigenous culture evident in artists such as Joseph Henry Sharp, among others.

Hemisphere

This sub-section looks at the territorial, political and economic expansion in the United States towards the west, north and south in the country’s attempt to replace Europe as the sphere of influence on the American continent. The Falls of Saint Anthony, painted by both George Catlin and Henry Lewis, exemplify that progressively occupied but seemingly unaltered natural space, while the landscapes of Latin America by Church, Bierstadt and Heade reflect the discovery of those exotic locations, of commercial expeditions that set out in search of land for cultivation and zones for starting up intercontinental maritime transport. Remote terrains continued to provide a source for artistic experimentation for Winslow Homer in the second half of the 19th century and Andrew Wyeth in the 20th century.

Interactions

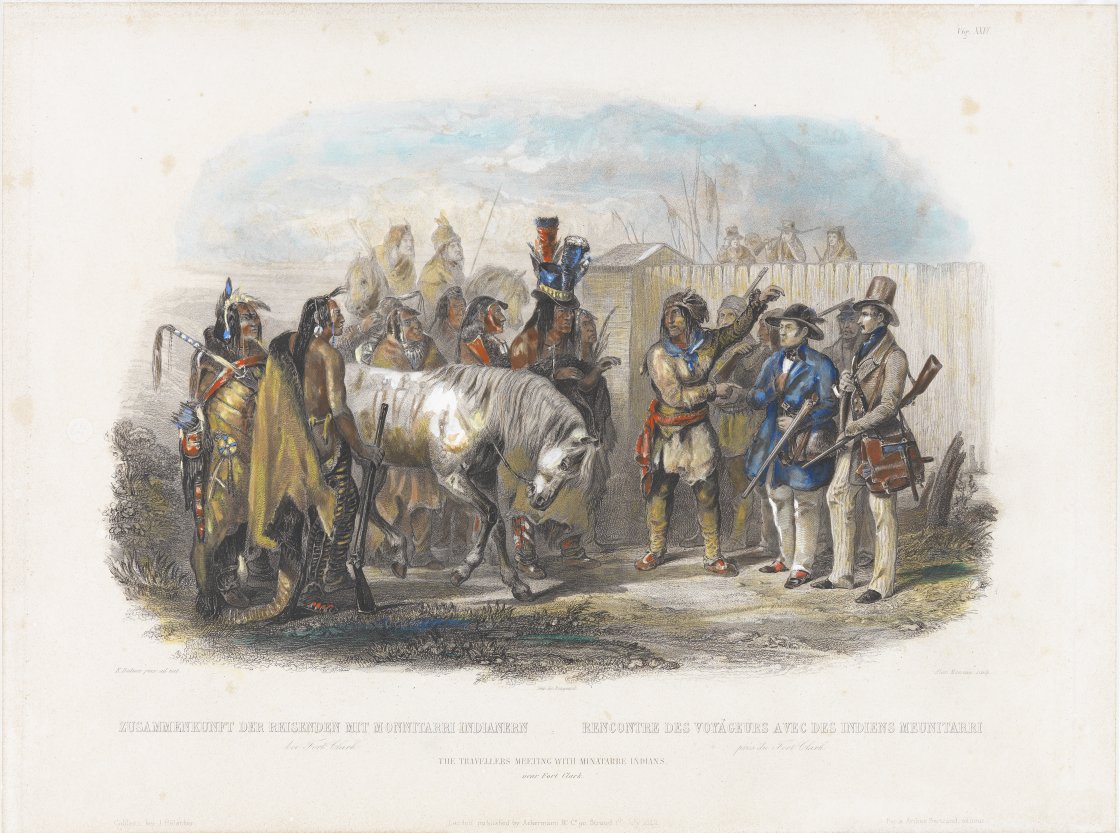

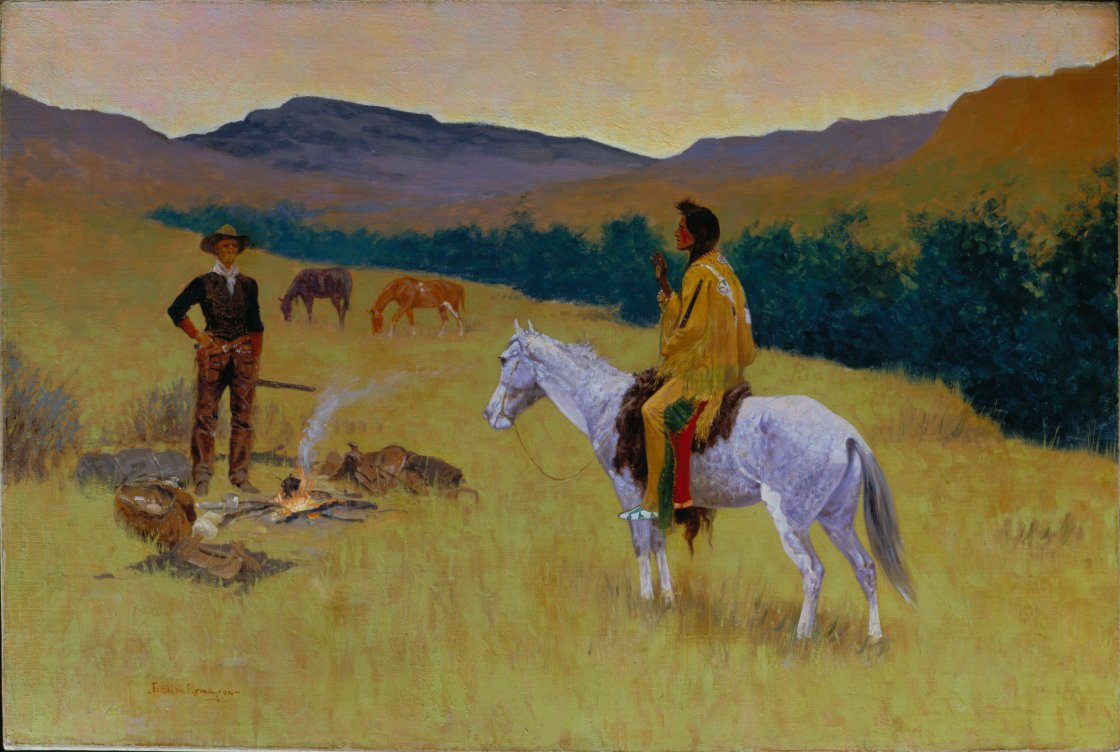

Interactions brings together works that represent the different communities of the United States - slaves, the working class, Jewish emigrants, Afro-Americans, Asians, cosmopolitans - analysing their interconnections which ranged from alliance to conflict. On display are the famous prints of indigenous peoples by Karl Bodmer, shown alongside portraits of the colonists who posed for John Singleton Copley and members of high society painted by John Singer Sargent. A focus on the exotic reappears with Frederic Remington in the early 20th century while interest in the working class and the Afro-American community is present in the work of Ben Shahn and Romare Bearden in later decades.

3. URBAN SPACE

This section reflects on modern American culture through artists’ gazes and on the growth and transformation of the urban space, the setting for a new society and the emergence of modernity.

The City

The mass migration of the Afro-American population following the civil war to cities in the north, in addition to major waves of European immigration transformed cities into spaces of encounter between different cultures. In turn, their appearance was transformed by industrial development, transport systems, and large avenues and skyscrapers, all of which inspired artists. Charles Sheeler compared streets and avenues with the geological formations of canyons; Max Weber expressed his experience of the city through the influence of Cubism and Futurism; while John Marin, who was associated with the European avant-gardes, conveyed the vital energy of the metropolis.

In the 1960s the new realist movements once again looked at the city from ground level, such as Richard Estes’ famous urban views and the city dwellers portrayed by Richard Lindner; people moving through the streets and around shopping malls. Outside the city but linked to it, Ralston Crawford’s Overseas Highway functions as a symbol of the freedom and independence of the American dream.

Modern Subject

Some artists focused their gaze on city dwellers not as representatives of an urban type but as individuals hidden among the crowd, convinced that it was those individuals’ personal stories that created the beat of the city. The key figures in many of these narratives are women, both in the public and private spheres and reflecting general changes in society. This is evident in the work of Winslow Homer in the late 19th century and Edward Hopper in the 20th century, artists who presented their particular vision of urban reality as a symbol of modern man’s isolation; or in the work of Raphael Soyer who depicted the new roles occupied by women, either at work or as the targets of new consumer practices. Another dimension to the modern subject appears in the paintings of Arshile Gorky, expressed through a style midway between Surrealist automatism and Expressionist gestural freedom; and in those of Willem de Kooning who reflected the dynamic energy of human beings.

Leisure and Urban Culture

In parallel to the industrial revolution the concept of leisure emerged in large cities and people could now devote the free time gained by shorter working hours to rest and entertainment. The creation of the first public parks and the increasing popularity of walking in the countryside or on nearby beaches - an escape mechanism for city dwellers - became the subject of scenes by Winslow Homer and the Impressionists Childe Hassam, John Sloan and William Merritt Chase, among others.

At a later date amusement parks and street music would inspire Ben Shahn, who aimed to portray his country’s social reality. From the early 20th century music became extremely important in American life. Of all the new musical forms it was jazz - which was Afro-American in origin and can be seen as the result of that urban cultural interchange - which undoubtedly became most popular and inspired numerous artists including Arthur Dove, Stuart Davis and even Jackson Pollock. Even at the start of the century music was a model for various painters such as Marsden Hartley and John Marin, who saw musical analogies as an alternative unconnected with appearances.

4. MATERIAL CULTURE

This section analyses the renewed attention that material culture has received in American art, organised into three sub-sections:

Voluptas

The celebration of life and the senses through pictorial representation, summarised in the Latin word “voluptas”, begins with various still lifes, from the most traditional example, such as the 19th-century example by Paul Lacroix, to the most innovative ones by Stuart Davis, an artist who aspired to create a national, modern art through the everyday. Other painters including Charles Demuth, Georgia O’Keeffe, Lee Krasner and Patrick Henry Bruce also aimed to reconnect art and nature through a formal treatment that started with reality and progressively evolved towards abstraction. In addition, the interaction between the human and non-human became a recurring motif in the still lifes that Pop artists employed to reflect on consumer society, evident in the work of Tom Wesselmann, Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist.

Tempus fugit

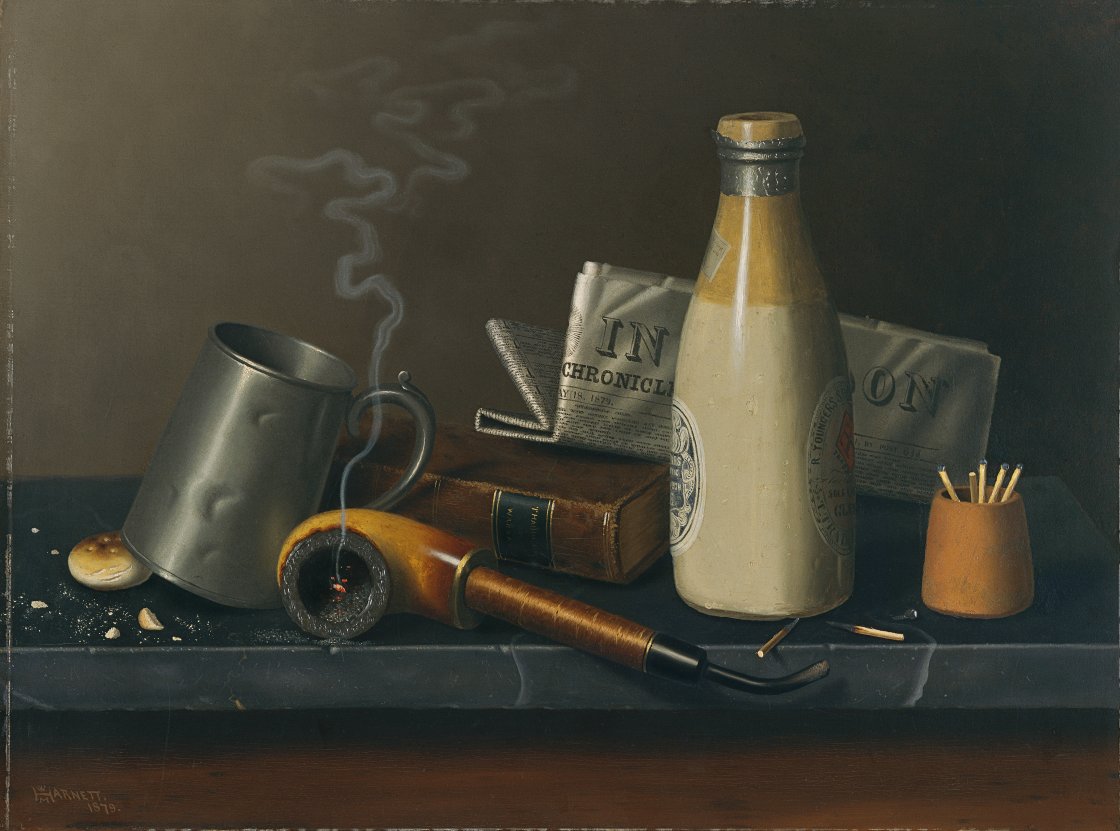

Alluding to the passing of time and the inevitability of death is a common device within the genre of still life. Tobacco smoke, spent matches, biscuit crumbs and a newspaper refer to that transitory nature of life in the painting by William Michael Harnett, one of the principal exponents and innovators in this genre in late 19th- and early 20th-century America. Mortality was also a recurring theme for Joseph Cornell, whose assemblages include animals and a range of other motifs such as soap bubbles which are employed to represent the ephemeral nature of life.

Rituals

The different cultural expressions of the country’s indigenous nations were the subject of interest by some foreign artists, such as the Swiss-French Karl Bodmer whose prints offer a visual inventory of the instruments, ritual objects and weapons of the different tribes, depicted both in isolation and in their context in everyday scenes of the village and its outskirts, and in landscapes with sanctuaries and burial grounds. Other artists expressed nostalgia for that idealised world, such as Frederic Remington who portrayed a romantic idea of the West and its inhabitants.

Publication