Centre Pompidou

20 October 2021 – 7 March 2022

Curators Bernard Blistène and Pamela Sticht

Excellent article - lots more images

Born in 1938, Hans-Georg Kern (his real name) was marked by his childhood in Saxony during the Nazi period and by the atrocities of war he was witness to. He was born in the village Großbaselitz (renamed Deutschbaselitz in 1948) which inspired the pseudonym he adopted in 1961. As of 1949, he grew up under the authoritarian regime of the German Democratic Republic, where abstract painting was prohibited, as an alleged expression of ‘capitalist decline.’ 1

In 1956, young Baselitz enrolled in the Hochschule für bildende und angewandte Kunst in Weissensee, East Berlin, and began studying painting under Walter Womacka (1925-2010), who was to earn a reputation as one of the most significant representatives of social realism in the GDR. When Baselitz began to draw on the work of Picasso for the paintings he produced in school, he was expelled, according to his teachers for a lack of ‘socio-cultural maturity’. He thus decided to cross the border and pursue his studies at the Staatliche Hochschule für bildende Künste in West Berlin, where, through Hann Trier’s international class, he discovered the artistic movements adopted by West German artists at the height of the Cold War, such as the informal art developed in France or American abstract expressionism.

Determined not to adhere to the prevailing ideologies and to find a means to express his anger at the situation of his divided country, Baselitz was drawn towards non-conformist artists such as Edvard Munch, Antonin Artaud, Lautréamont, or Mikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel, as well as the works of artists suffering from mental illness. He formed a particular interest in those artists examined by doctor and theorist Hans Prinzhorn, whose collection had been included by the Nazis in the 1937 exhibition of degenerate art. In the work published by Prinzhom in 1922, Expressions de la folie [The plastic activity of the mentally ill], Baselitz discovered a drawing that was to inspire his self-portrait G.- Kopf [G. Head] (1960-1961), presented at the entrance to the exhibition alongside the work G. Antonin (1962), a tribute to Artaud.

In October 1961, these texts and discoveries incited the enraged artist to write the Pandämonisches Manifest with the help of his friend Eugen Schönebeck. The title is a reference to Satan’s palace, Pandæmonium, from John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (1667),

an imaginary place which echoed the post-apocalyptic aspect of Germany in 1945. This was followed by a first series of paintings which caused a scandal when presented at his debut exhibition at the Werner & Katz gallery in West Berlin in 1963. Die große Nacht im Eimer [The Big Night Down the Drain] (1962-1963) and Der nackte Mann [The Naked Man] (1962) were both confiscated by the West Berlin authorities for their ‘pornographic character’.

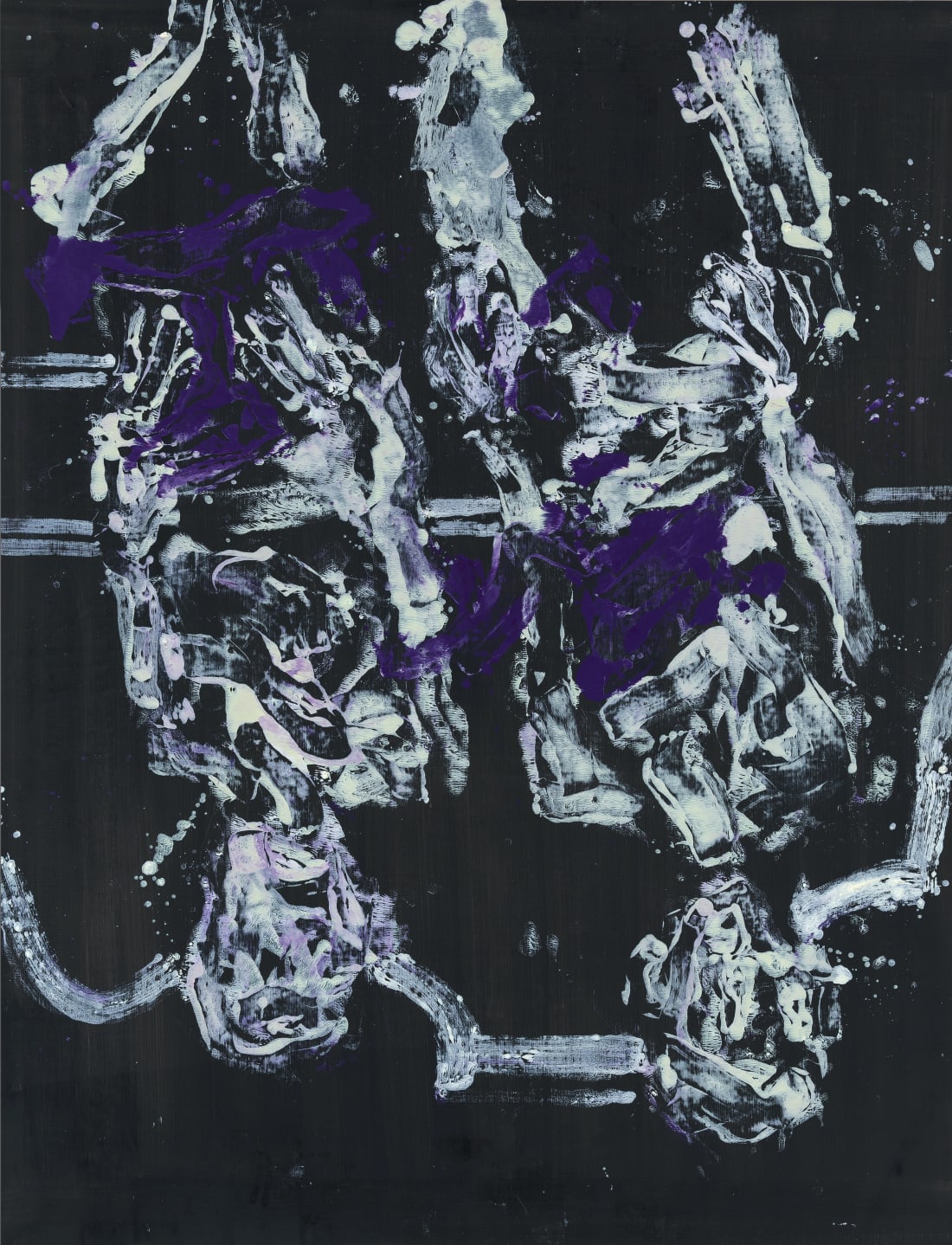

Die Mädchen von Olmo II [The Girls of Olmo II]

1981

Oil on canvas

250 × 249 cm

Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

© Georg Baselitz 2021

Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI B. Prévost Dist. RMN-GP

Curated by Bernard Blistène and in association with the artist, the Centre Pompidou presents ‘Baselitz – The Retrospective’, in Gallery 1. This is the first all-encompassing exhibition of the German artist born in 1938. Six decades of creation are presented along a chronological path highlighting the key periods in the artist’s work. From his initial paintings to the Pandemonium Manifesto of the early 1960s, the Heroes series or the Fractures series of upside-down motifs, begun in 1969, the exhibition also showcases successive ensembles of works in which Baselitz experimented with new pictorial techniques. Various forms of aesthetics unfold, fuelled by references to art history and Baselitz’s intimate knowledge of the work of many artists, such as Edvard Munch, Otto Dix and Willem de Kooning. The exhibition also features his Russian paintings and self-reflective works, Remix and Time. Unclassifiable, vacillating between figuration, abstraction and a conceptual approach, Georg Baselitz claims to paint images that have yet to exist and to unearth that which has been relegated to the past

Intimately linked to the artist’s experience and imagination, Georg Baselitz’s powerful work testifies to the complexity of life as an artist in post-war Germany and reveals his endlessly renewed questionings; on the possibilities of representing his memories, variations in technique and traditional motifs of painting, aesthetic forms developed over the course of art history, and the formalisms dictated and conveyed by the various political and aesthetic regimes of the 20th and 21st centuries.

1. Further to a decision by the General Committee of the SED [East German Communist Party] on 17 March 1951, ‘in the fight against formalism in literature and art for a progressive German culture’, the Secretary General of the SED party, Walter Ulbricht, declared before the Volkkammer on 31 October 1951: ‘We no longer want to see abstract images in our art schools (...). Grey on grey painting, the expression

of capitalist decline, is a flagrant contradiction of contemporary life in the RDA.’ 5

Keeping to dark hues and evoking Théodore Géricault’s preparatory drawings for Le Radeau de la Méduse [The Raft of the Medusa] (1818-1819), Baselitz painted P. D.- Füße [P.D. Feet] between 1960 and 1963, a group of fragmented images of brutalised feet with open wounds, brushed with a thick, pasty matter. The painting Oberon (1. Orthodoxer Salon 64 – E. Neijsvestnij) [Oberon (1st Orthodox Salon 64 – E. Neïzvestny)] (1963-1964) is a sort of hallucinatory self-portrait as the King of the Elves, in which the multiple heads resemble that of Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), a motif which the artist would use again for his first series of soft varnishes, presented in the exhibition next to a selection of water colours and ink and pencil drawings.

While Pop Art and the emergence of new critical movements dominated the West German art scene, and following a residency in Florence, Baselitz decided to create a new form of German painting and continued working, up to mid-1966, on a cycle with the provocative title Ein neuer Typ [A New Type], also known as Helden [Heroes]. Partisans, painters or poets, the war-wounded and survivors compose a gallery of figures whose disproportionally-sized bodies are also characterised by their mannerist distortions. Every figure presents a specific narrative attribute, in keeping with the tradition of Medieval pictorial art. Each of these works can be interpreted as a self-portrait, a pictorial exploration of an event, a historical figure or a painter, such as the tribute paid to Gustave Courbet with the painting B.j.M.C.– Bonjour Monsieur Courbet (1965). The series culminates with the large-format manifesto- painting Die großen Freunde [The Great Friends] (1965), which expresses all the tragedy of Germany through two wounded survivors, incapable of holding hands and standing among ruins, a patched-up flag lying on the ground.

In his following works, the images of human figures became increasingly segmented and other motifs made their appearance.– figures, dogs or trees, with a series entitled Frakturbilder [Fractures]. In B für Larry

[B for Larry] (1967), the tree, a symbol of the myth of the transcendence of the German soul appears to shatter the body of the figure inspired by the canons of ancient art and revived by the Nazi regime. This new pictorial research led Baselitz to create Der Mann am Baum

[The Man by the Tree], in which the motif is partially reversed.

The upside-down motifs were to become the artist’s signature, allowing him to concentrate more on painting and to create new images by relegating the motif to the middle ground: ‘If you want to stop constantly inventing new motifs, but still want to go on painting pictures, then turning the motif upside down is the most obvious option. The hierarchy of sky above and ground down below is in any case only a pact that we have admittedly got used to but that one absolutely doesn’t have to believe in.’ 2

Experiments with matter and emblematic motifs became the artist’s main focus, such as that of the eagle in Fingermalerei – Adler [Finger Painting – Eagle], (1972), a reference both to the animal he had observed as a child in Saxony-Anhalt and the German coat-of-arms. His next paintings entered into a dialogue with the world of Edvard Munch, or Emil Nolde, as in Die Mädchen von Olmo II [The Girls of Olmo II] (1981), as if he wanted to create new links with the Nordic artistic tradition of the pre-National-Socialist regime. Alongside his painting, Georg Baselitz also produced engravings, while experimenting different techniques and varying his motifs. Around the year 1977, he began collecting African sculptures, which would inspire the creation of Modell für eine Skulptur [Model for a Sculpture] (1979-1980), his first sculpture for the German pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale.

The title of this work was a reference to its deliberately unfinished aspect, and the posture of the ancestral figures of the Lobi people, arms raised to the sky and palms facing upwards, was nevertheless instantly associated by the German press and public with the Nazi salute, causing yet another controversy in Germany and confirming Baselitz’s reputation as a provocative enfant terrible. Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Georg Baselitz re-immersed himself in his memories of the war, notably with the series of sculptures entitled Dresdner Frauen [Women of Dresden] (1989-1990), his tribute to ‘Trümmerfrauen’, or the women who had helped to rebuild German cities after 1945.

Dresdner Frauen – Die Elbe

[Women of Dresden –The Elbe]

1990

Ashwoodand tempera

154 × 65 × 67 cm

Collection Thaddaeus Ropac London • Paris • Salzburg • Seoul

© Georg Baselitz 2021

Photo Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

In 1991, he began working on the Bildübereins series [Picture over another], in which he superimposed increasingly abstract motifs and played around with the principle of ornamentation, while retaining traces of certain figures that fascinated him. These ‘superimpose a duality which is never the same and always the same. They have this aspect of memory and underground listening.’ 3

Between 1998 and 2005, Georg Baselitz revisited the images of his East German childhood in a series entitled Russenbilder [Russian Paintings]. In particular, he re-interpreted Anxiety (1986), a work by an emblematic artist of Russian socialist realism, Gely Korzhev [1925-2012], with his painting Anxiety I (Kozhev) (1999), using a deliberately haphazard technique in which the two heads of the figures were placed off-centre and horizontally to float in the middle of two enormous red spots.

In 2005, Georg Baselitz began his Remix cycle, through which he forged a more explicit pictorial dialogue with the artists who had inspired him, or with his own works, starting with Die große Nacht im Eimer (Remix) [The Big Night Down the Drain (Remix)] (2005), and its recognisable portrait of Adolf Hitler, or Die Mädchen von Olmo (Remix) [The Girls from Olmo (Remix)] (2006): ‘When you look at history, what do you see? Lots of artists also painted remixes of their works, Munch I don’t know how many times, Picasso in his last period, Warhol while he was still young. Why not me?’ 4

2. G. Baselitz, Georg Baselitz im Gespräch mit Heinz Peter Schwerfel, in Georg Baselitz, Kunst Heute, n° 2, Cologne, Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1989, p. 24. In English: ‘Georg Baselitz in conversation with Heinz Peter Schwerfel’ (trans. Fiona Elliott), in Georg Baselitz, Collected Writings and Interviews, ed. by Detlev Gretenkort, London, Ridinghouse, 2009, p. 154

3. Éric Darragon, in Baselitz, Charabia et basta – Entretiens avec Éric Darragon

[Interviews with Éric Darragon]. Publ. by L’Arche,1996, p.178.

4. Cit. G. Baselitz in an interview with Philippe Dagen, L’oeuvre de Georg Baselitz envahit les musées de Baden-Baden [The work of Georg Baselitz invades the museums of Baden- Baden], published 21 November 2009 in Le Monde newspaper. 6