Almine Rech New York, Upper East Side

January 9 to February 22, 2025

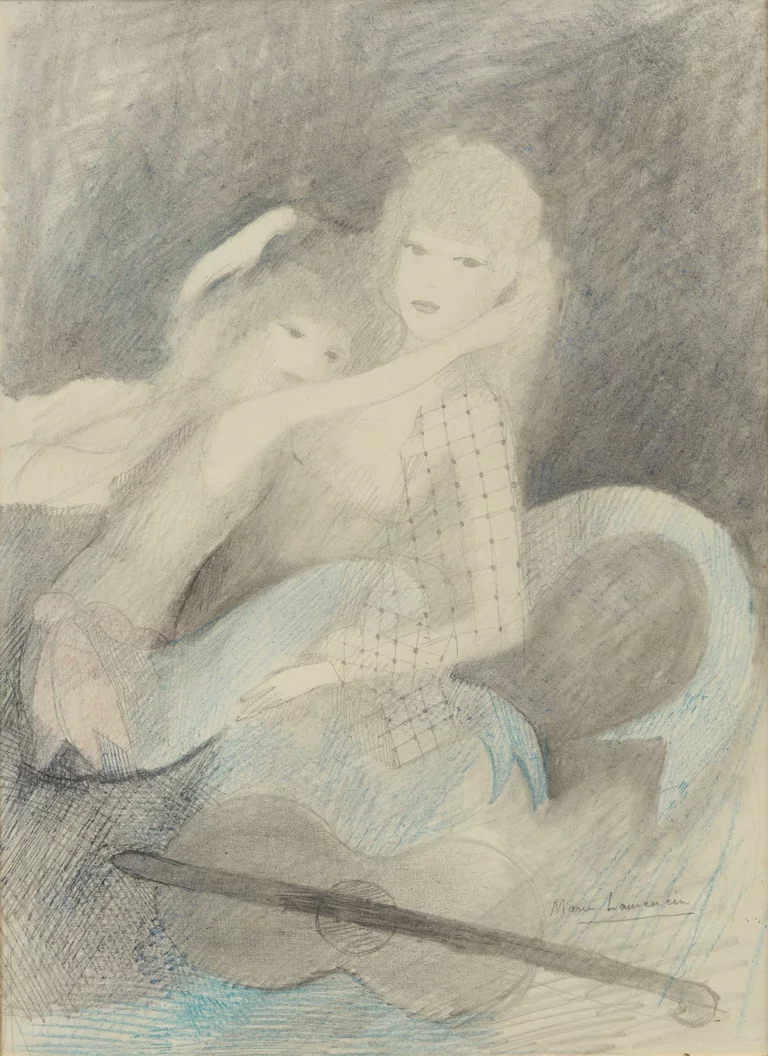

Marie Laurencin Jeune fille à la mandoline, 1935

Oil on canvas

60.9 x 50 cm, 24 x 19 3/4 in (unframed)

93 x 81.9 x 8.6 cm, 36 5/8 x 32 1/4 x 3 3/8 in (framed)

In a 1952 article for TIME, the French artist Marie Laurencin was asked about her unwavering interest in the female form. Born in 1883, she had been producing paintings, watercolors, and drawings depicting elegant young women since her twenties. Now in her late sixties, she indicated to the TIME journalist that she had no intention of changing course. “Why should I paint dead fish, onions and beer glasses?” she quipped. “Girls are so much prettier.”

As these words suggest, Laurencin was never one to shy away from the title of woman artist, embracing all things girlish with little hesitation or apology. During her long and storied career, she not only elevated female sitters—she rarely chose to represent men—but also cultivated a deliberately dainty aesthetic, favoring pastel tones, naïve storybook figuration, and airy brushstrokes. Her pretty pictures of pretty girls were more than just an ode to the power and allure of the feminine. They also functioned as visual expressions of Laurencin’s fluid sexual identity, which caused her pursue love affairs with both men and women. As a recent retrospective at the Barnes Foundation contended, the artist possessed a singular queer aesthetic that "subtly but radically challenges existing narratives of modern European art."

For its pleasing surface and transgressive subtext, Laurencin’s oeuvre was commercially and critically celebrated in her lifetime but fell into relative obscurity after her death in 1956, as the art world turned its eyes from Paris to New York and the masculine swagger of Abstract Expressionism. Thanks to recent curatorial and scholarly efforts, however, Laurencin is being returned to her rightful place in the history of modern European art. Marie Laurencin: 1905– 1952 joins in international reappraisals of the artist, showcasing over twenty works that trace the evolution of her practice from early student experimentations to mature compositions.

Laurencin trained in porcelain decoration before enrolling, in 1904, in painting lessons at the Académie Humbert alongside Georges Bracque. Through Bracque, she met Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire, with whom she became romantically involved. She quickly became part of the Cubist inner circle and began to emulate their style, incorporating flatness and fragmentation into her work, as exemplified in Portrait of Clara d’Ellébeuse (1908).

By the 1910s, she had grown weary of Cubism and ended her formal relationship with the movement. Her interest in abstraction remained but she started taking inspiration from other sources, among them, the decorative arts and the romance and finery of the rococo. As demonstrated in Jeune Fille (1914), her figures grew soft and willowy, and her color scheme, pale and powdery. For her alluring marriage of modernism and nostalgia, she earned the attention of famed modernist dealer Paul Rosenberg. Presented in Portrait d’un Homme (1913/14), he would represent Laurencin from 1921 until her death. (A number of the works included here were displayed in Rosenberg’s Paris and New York galleries.)

The years leading up to World War I also saw her break things off with Apollinaire. In his place, she married a German count and started an affair with Nicole Grout, sister of couturier Paul Poiret. The tryst would outlast the short marriage, dissolved in the early 1920s, as would Laurencin’s interest in queerness. Throughout the interwar period, she was a regular guest of Natalie Clifford Barney’s sapphic salon—alongside figures like Sylvia Beach, Tamara de Lempicka, and Gertrude Stein (an early patron)—and peppered her work with allusions to same-sex love and lust.

Many of Laurencin’s trademark motifs doubled as emblems of lesbianism. She often painted compositions that included female deer, in French, les biches, a slang term for gay women. She likewise enjoyed depicting female friends, and Les deux amies, noir et bleu, jaune et rose (c. 1922/23) is one of many Laurencin pieces to seize upon the ambiguity of the term amie, which, like the English “girlfriend,” can refer to a platonic or romantic mate.

Laurencin also painted women in close, sensuous contact. Dancers float across stages and ballroom floors devoid of male partners. Two mermaids embrace, their tails coiling around each other’s torsos. Equestrians ride off into the distance with thighs exposed. Why, indeed, should Laurencin paint still lifes of “dead fish, onions, or beer glasses” when there was so much to explore in the rich and multilayered world of women and their desires?

IMAGES