| Albertina, Vienna |

| 8 September–3 December 2017 The Albertina is devoting a comprehensive exhibition to Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the 16th century’s most important Netherlandish draughtsman. With its 80 works, this exhibition presents the entire spectrum of Bruegel’s drawn and printed oeuvre and seeks to shed light on his artistic origins by juxtaposing his output with high-quality works by important predecessors such as Bosch and Dürer. Included are around 20 of the Dutch artist’s most beautiful drawings from the museum’s own extensive holdings as well as from international collections, a selection that also brings together two of his final drawings—Spring and Summer—for the first time in many years. Furthermore, numerous printed treasures—sought out and painstakingly restored at the Albertina over the course of long-running research efforts—are being shown for the first time. Humanity’s Tragedy and Greatness Pieter Bruegel’s drawings, done on the eve of the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule and amidst an era of political, social, and religious transformations, conjure up a complex pictorial world. Bruegel reflects on social conditions in away that is humorous, down-to-earth, perceptive, and deeply critical. And as a moralist, he makes a theme of human beings’ tragedy and greatness, ridiculousness and weakness. Bruegel’s works stand out for his immense interest in the real world inhabited by his contemporaries: they feature peasants working in the fields, picturesque landscapes, alpine peaks, and intimate river valleys, but also numerous satirical and moralising takes on contemporary society as well as absurd and comical grotesques. The portrayal of the individual recedes in favour of illustrations of specific archetypes. At turns keenly observant of nature or engaging in parodic exaggeration, the artist the constant conflict between ideal and reality from various angles. His penchant for therough-hewn and folksy, along with unsanitised impressions of social conditions, is something that he has in common with the roughly contemporary authors Rabelais, Cervantes, and Shakespeare, who, in their literature, turned the world into stage and formulated universal insights, while his deeply moral approach is akin to that of Michel de Montaigne or Francis Bacon.  In Bruegel’s most famous drawing—The Painter and the Connoisseur, one of the masterpieces held by the Albertina—the artist makes a theme of art production itself: he confronts viewers with the serious, intellectual work of the painter, in response to which a purported art connoisseur can do nothing but gape perplexedly and reach into his purse. In this work, art meets with the incomprehension of the buyer and of society at large. Numerous Precious Works Rediscovered Pieter Bruegel the Elder is one of the 16th century’s foremost draughtsmen. Even during his lifetime, his drawings enjoyed the greatest popularity and were coveted collector’s items—with many also being reproduced as copperplate prints and widely disseminated. His audience consisted not of the peasants who so often populated his pictures, but rather of the educated elite. Alongside The Painter and the Connoisseur, the Albertina owns five other drawings from Breughel’s own hand—meaning that alongside those of the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin and the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, this is one of the world’s largest collections of his rare drawings, of which only around 60 are extant. The Albertina is also one of a very few collections worldwide that own the artist’s entire printed oeuvre—with many of them even present in multiple examples, including numerous rarities and even a few unique state proofs. Most of the Albertina’s rich holdings of early Netherlandish, Dutch and Flemish art were acquired by Albertina founder Duke Albert and by the former Imperial Court Library. Bruegel’s work in the Albertina has been analysed over several years of research. In the process, numerous precious works have been rediscovered, works such as a large-format view of Antwerp by a Bruegel contemporary of which only one further copy is known. Many of these have never before been exhibited and were therefore given conservational attention for the very first time. In light of the countless publications and exhibitions on Bruegel, it may come as a surprise that new finds of works by such a famous master can still occur—which is why it is all the more cheering to have discovered over 100 additional copies of prints by Bruegel, works previously unknown to researchers, that have now been restored for this exhibition with the utmost care. "Experiencing the Alps On his travels, he drew many views from life, so that it is said that, when he was in the Alps, he swallowed all the mountains and rocks and then spat these out again onto panels".Karel van Mander, 1604 In 1552, Pieter Bruegel traveled to Italy in the company of his friend, the cartographer Abraham Ortelius. After his return, he captured the impressions gathered during the journey over the Alps in his Large Alpine Landscape  Soldiers at Rest (Milites Requiescentes) from The Large Landscapes  The Penitent Magdalene (Magdalena Poenitens) from the series The Large Landscapes and in the series of the Large Landscapes: wide panoramas of the alpine mountains featuring steep cliffs, meandering rivers, and tiny trees and houses. In view of this unprecedented closeness to reality, Bruegel’s biographer Karel van Mander admiringly wrote in 1604 about the artist’s ability to directly translate what he had seen into a picture. The Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Cock disseminated Bruegel’s drawings in the form of engravings. This meant a steady income for the young artist, for the revenue from reproducible prints was more lucrative than the sale of individual drawings. Bruegel’s alpine views enjoyed widespread renown and established his role model function as a draftsman of landscapes far beyond his death. Engraved Ethics "Many of his bizarre and highly evocative compositions have been engraved into copper. On his deathbed, however, he instructed his wife to burn a large number of these fine and neatly drawn and inscribed satires, which are in some cases all too biting and imbued with sarcasm, either because he regretted having done them, or because he feared that they could have unpleasant consequences for his wife. "Karel van Mander, 1604 Whereas Bruegel’s earliest surviving drawings deal exclusively with landscape subjects, from the second half of the 1550s onward his artistic interest increasingly focused on man and his relationship to society: produced in close cooperation with the Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Cock, engraved illustrations of proverbs, genre scenes, and moralizing allegories became one of the artist’s trademarks. The criticism of foolery, excessive greed, and boundless egoism in particular were important themes in and around the proto-capitalist mercantile city of Antwerp. What all of the moralizing prints have in common is the fundamental significance of the accompanying captions, which provide an additional verbal level of interpretation. The interplay between image and text invites the viewer to evaluate and actively interpret both the thematic overlaps and omissions. Van Mander’s statement that the artist had these works burned before his death because of their socio-critical content must presumably be understood as an embellishing anecdote, yet it nevertheless testifies to the explosive nature ascribed to Bruegel’s pictures. A New Bosch "Who is this new Hieronymus Bosch for the world, versed in imitating the master’s ingenious dreams with such great skill of paintbrush and pen –so that sometimes he surpasses even him." Dominicus Lampsonius, 1572 Beginning in the 1550s, Bruegel closely followed the pictorial inventions of the Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450 –1516). The latter’s depictions of fantastic hybrid creatures and devils were well known far beyond the country’s borders and coveted collectables. In terms of the salability of his prints, it was thus a clever move by the young Bruegel to adopt his predecessor’s pictorial idiom. In collaboration with the publisher Hieronymus Cock, he led a revival of Bosch’s art and became its most important exponent. For example, the engraving  Big Fish Eat Little Fish, based on Bruegel’s drawing, contains an ambiguous reference to Bosch as the inventor of the motif, whereas Bruegel’s name was not yet mentioned at this early stage in his career. Bosch, who already had had many followers during his lifetime, was widely imitated. Such themes as the Temptation of Saint Anthony, Christ’s Decent into Hell, and The Last Judgment offered ample opportunities to depict the monstrous creatures that were so popular on the art market. Unlike other followers, Bruegel ingeniously knew how to elaborate on Bosch’s language of form and motif, so that the humanist writer Dominicus Lampsonius praised him as the “new Hieronymus Bosch.” Diablerie and Drollery: The Seven Deadly Sins “He worked very much in the manner of Hieronymus Bosch, and was thus called by many “Pieter the Droll.” There are few pictures by his hand which even the serious viewer can contemplate without laughing—indeed, however reserved and morose he might be, he cannot help but at least smile”.Karel van Mander, 1604 The series of the Seven Deadly Sins, drawn in 1556 and 1557 and engraved in 1558, depicts  Pride (Superbia), Envy (Invidia),  Wrath (Ira),  Avarice (Avaritia),  Sloth (Desidia), Gluttony (Gula)  and Lust (Luxuria) as female personifications accompanied by their symbolic animals –peacock, turkey, bear, toad, donkey, pig, and rooster. The female protagonists, placed in the center of the composition, are shown against a high horizon and surrounded by figures, animals, and hybrid creatures exemplarily visualizing the respective vices in a number of narrative scenes. The personifications themselves similarly succumb to the sins they embody: for example, Invidia enviously devours her own heart; Ira wages a war; Desidia sleeps; and Gula guzzles. Whereas Bosch had created a sinister world full of sinfulness and often cruel punishment in his pictures, the works of Pieter Bruegel were always also marked by a comical component. For instance, the depiction of Gluttony shows a gourmand pushing his paunch in front of him in a wheelbarrow, while in the allegory of Sloth a sluggard emptying his bowels is supported by several small figures poking him with their lances. The crude humor of this scene would have been unthinkable before. Throughout his life, Bruegel remained eager to discuss in his pictures the fundamental moral problems of his politically and socially turbulent environment. Drinking, Dancing, Reveling: The Peasants’ Kermises “Nature was wonderfully felicitous in her choice when, among the peasants of an obscure village in Brabant, she selected the quick-witted and humorous Pieter Bruegel to become a painter so that he could depict the peasants”.Karel van Mander, 1604 Images of peasants comprise only a small part of his oeuvre, and it was not Bruegel who invented the peasant genre. The first peasant pictures can already be found in the calendars of devotional literature and in prints by Albrecht Dürer. From the 1550s onwards, depictions of the rural population’s cheerful celebrations enjoyed great popularity on the Antwerp art market. Pieter Bruegel stages thelively hustle and bustle of peasants in the center of a Flemish village, withanimals roaming freely and mingling with the revelers. The target audience of the engravings was, of course, not the peasants depicted in them, but rather the urban population. Documenting local customs, these images simultaneously visualize them for the urban consumer in an aesthetically pleasing manner as both information and entertainment. The art historiographer Karel van Mander reports that Bruegel frequently went to kermises dressed in a traditional peasant’s costume or mingled among the guests of a wedding party in order to capture rural life in pictures. Although this anecdote was more likely born from Van Mander’s fantasy, it has strongly influenced our idea of Bruegel as a masterly painter of crude but merry country life to this day. In his famous season pictures, Bruegel directly picks up on the depictions of the months in medieval books of hours. His magnificent drawings Spring and Summer served as designs for a planned series of engravings. In Spring, flower beds are planted and sheep sheared, with courting couples in the right background suggesting a tender springtime atmosphere. Summer shows simple peasants working in the fields near a village: grain is cut, bundled, and carted off. Compared with the highly detailed kermis pictures, the depictions of the seasons reveal a new three-dimensionality and monumentality of the figures. In Summer, a farmhand refreshes himself with a drink from an enormous jug. His bare foot and the blade of his scythe extend beyond the frame of the landscape scene to the zone of the legend, which lends the composition a high degree of immediacy. The vibrant, delicate pen drawings are distinctly different from the more rigid and schematic lines in the engravings for which they served as models. Bruegel was not able to realize the planned scenes for Autumn and Winter before his death. Therefore, in 1570, his Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Cock asked the landscapist Hans Bol to deliver the two missing sheets, so as to be able to publish the complete cycle of the four seasons. In the Latin captions a connection is made between the seasons and the ages of man: from childhood in Spring and youth in Summer to maturity and old age in Autumn and Winter. On Art and Artists One might call drawing the father of painting, and indeed also the proper access or gateway to many other art forms, such as that of the goldsmith or the architect. The seven liberal arts could also not exist without it, for the art of drawing encompasses all things Karel van Mander, 1604 In August 1566, a storm of iconoclasm raged in the Netherlands, which brought with it a hitherto unknown wave of destruction of art. As the result of a ban on images demanded by the reformers (“Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image”), works of art with Christian themes were obliterated throughout Europe. Hence Bruegel was a witness to a turbulent era, and in his most famous drawing reflected upon the production of art and the artist’s role: in The Painter and the Buyer he discusses creative work as an intellectual achievement that goes far beyond mere craftsmanship. Completely immersed in the creative act, the melancholically brooding artist despises the purely profit-oriented world of the purported art connoisseur, who over hastily reaches for his purse. Because of the insurmountable mental distance between them, the painter and the buyer are an unequal couple. That the painting the artist is in the process of completing is positioned outside the pictorial space invites the spectator to imagine the invisible masterpiece and thus imitate the mental process of creating a picture. This satirical depiction is Bruegel’s most personal and at the same time most radical work. In the age of iconoclasm, addressing the significance and freedom of art exposed an explosive topicality. The fact that Bruegel dealt with the very theme in a graphic medium was probably due to the spontaneity drawing permitted. However, it also fits in with the idea that drawing was the basis of all other arts. Biography Pieter Bruegel is born between1526 and 1530. His place of birth was a topic of dispute. According to his biographer Karel van Mander, Bruegel was born in the village of Bruegel in the Duchy of Brabant. Around 1545 he begins his artistic training, according to his early biographer Karel van Mander, in the Antwerp studio of Pieter Coecke van Aelst. In 1550/51, he collaborates on an altarpiece in the workshop of Claude Dorizi in Mechelen and becomes a member of the Antwerp painters’ guild as a “free master.” From 1552 to 1554, Bruegel undertakes a journey to Italy (a common practice among artists of his time), traveling to the Apennine Peninsula via Lyon and as far as the Strait of Messina. In 1553, he spends time in Rome. His crossing of the Alps is documented by numerous drawings. In 1554,after his return to Antwerp, Bruegel begins an intensive collaboration with the publisher Hieronymus Cock. He increasingly focuses in his works on the theme of man and his relationship to society. Beginning in 1556, numerous pictures are also created in the grotesque style of Hieronymus Bosch. Beginning in 1559, Bruegel signs his paintings in capital Roman letters “BRUEGEL” to emphasize the humanistic aspiration of his art. In 1563, the artist moves from Antwerp to Brussels and marries Mayken Coecke van Aelst, the daughter of his presumptive teacher. One year later, his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger is born, followed in 1568 by his second son Jan. The move to the royal seat brings the artist into the direct proximity of potential customers. In the last years of his career, the cast of figures in his works is increasingly reduced, and the individual becomes the main protagonist. In 1569, Bruegel dies in Brussels and is given a tomb in the church of Notre-Dame de la Chapelle. His sons, who both become painters, take over their father’s workshop and, through copies of his works, ensure the widespread renown of his oeuvre and a level of popularity that continues to this day. Catalogue

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Summer, 1568

Pen and ink

© Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk,

Photo: Christoph Irrgang

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The Painter and the Buyer, ca. 1565

Pen and ink

© The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Spring, 1565

Pen and ink

© The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder (Engravers: Jan and Lucas van Duetecum)

The Kermis of Saint

George, ca. 1559

Engraving

© The Albertina

Museum, Vienna

Pieter

Bruegel (Engraver: Pieter van der Heyden)

Elck, ca. 1558

Engraving

The Albertina Museum,

Vienna

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder

The Alchemist, 1558

Pen and ink

bpk /

Kupferstichkabinett, SMB / Jörg P. Anders

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder

The Ass at School,

1556

Pen and brown ink

Berlin,

Kupferstichkabinett

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder

The Descent of Christ

into Limbo, 1561

Pen and ink

© The Albertina

Museum, Vienna

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder

Sloth, 1557

Pen and ink

© The Albertina

Museum, Vienna

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder

Big Fish eat little

Fish, 1556

Pen and ink

© The Albertina

Museum, Vienna

Pieter

Bruegel the Elder (Engravers: Jan and Lucas van Duetecum)

Large Alpine

Landscape, 1555-1556

Engraving

© The Albertina

Museum, Vienna

The Rabbit Hunt, 1560

Etching

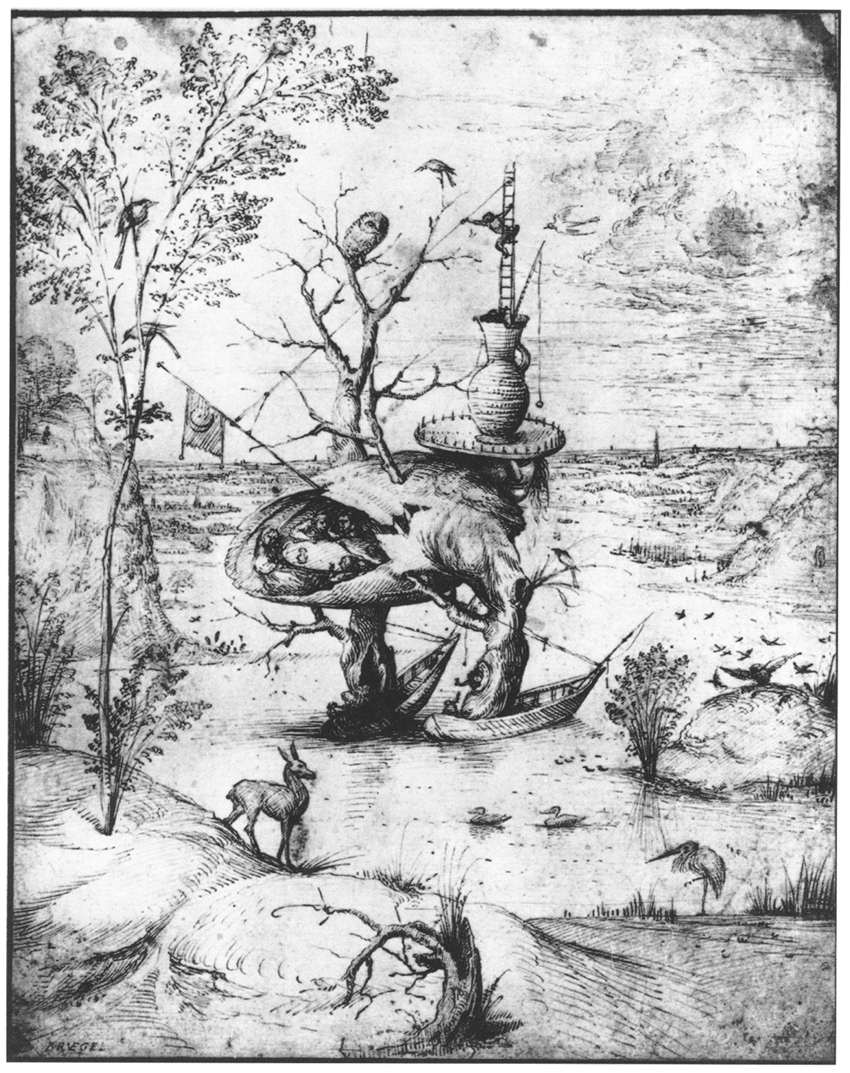

The Tree Man, ca.

1500

Pen and ink

© The Albertina

Museum, Vienna

|