The Amon Carter Museum of American Art will host the first major exhibition in the United States to explore the multifaceted meanings of hunting and fishing in both painting and sculpture from the early 19th century to the mid-20th century. Wild Spaces, Open Seasons: Hunting and Fishing in American Art is on view October 7, 2017, through January 7, 2018, and features more than 60 paintings and sculptures that together demonstrate the aesthetic richness and cultural importance of hunting and fishing in America. Admission is free.

“Hunting and fishing is a subject that captivated artists throughout the 19th and 20th centuries,” says Amon Carter executive director Andrew J. Walker. “Not mere pictures of wild game and fish, these paintings and sculpture show that the relationship between man and nature defined the American experience for artists as broad reaching as Winslow Homer and Charles M. Russell.”

Wild Spaces, Open Seasons includes a wide variety of genre scenes, landscapes, portraits and still lifes, including iconic and rarely seen works by Thomas Cole, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Andrew Wyeth, as well as key pictures by specialists such as Charles Deas, Alfred Jacob Miller, William T. Ranney and Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait. In addition, the show sheds new light on modernist interpretations of these subjects by George Bellows, Stuart Davis and Marsden Hartley. The works illuminate evolving ideas about community, the environment, national identity, place and wildlife, offering compelling insights into socioeconomic issues and cultural concerns. Capturing a communion with nature that was becoming increasingly scarce over the decades, many artists alluded to the country’s burgeoning industrialization and urbanization at the turn of the century.

The exhibition is organized into six thematic sections: Leisurely Pursuits, Livelihoods, Perils, Communing in Nature, Myth and Metaphor, and Trophies.

Leisurely Pursuits examines representations of hunting and fishing as recreational pastimes, often the province of society’s upper echelons, and the role of art making in navigating the social codes of leisure. Despite its European aristocratic origins, the hunt as an upper-class social ritual with strict codes of etiquette infiltrated but morphed in American democratic society. The portraits in this section display how the European tradition of representing sitters as gentleman-hunters was transformed in the American context, where hunting was central to the rugged exploits of folk heroes like Daniel Boone and later became legitimatized as a popular, hyper-masculine sport in the era of Theodore Roosevelt.

Livelihoods features images of commercial enterprise, necessity and sustenance involving different social strata. Many people—guides, frontiersmen, trappers—depended on the bounty of the forest and waterways for their well-being. While America’s expanding agricultural prosperity made hunting for sustenance less of an imperative, the fur trade and commercial fishing still generated income. The paintings in this section explore the ways in which hunting and fishing became a means of financial reward.

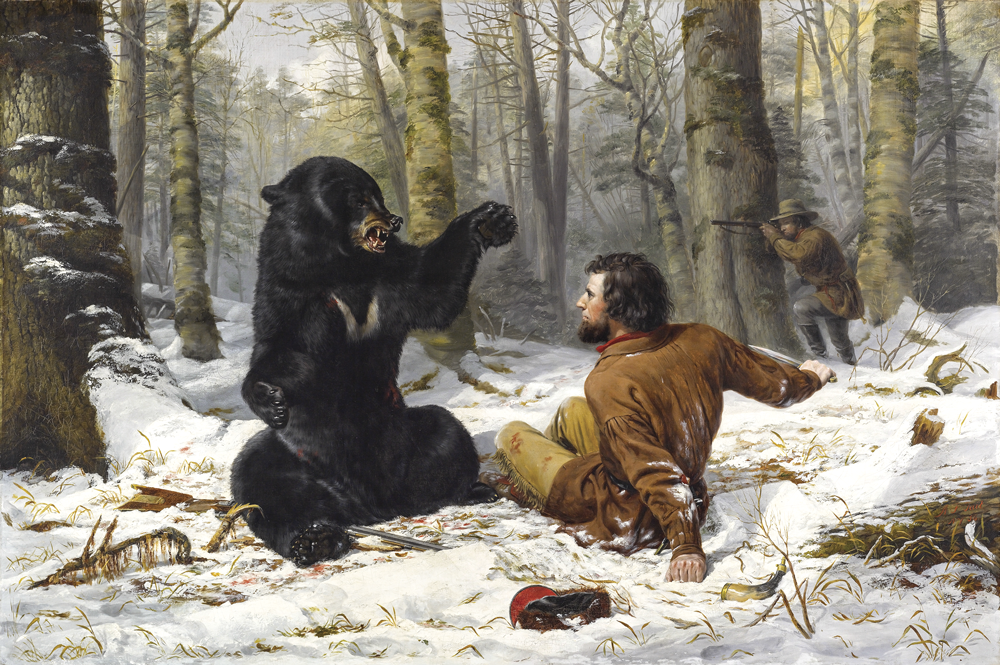

Suspense-filled and often sublime depictions of close calls, tights spots and struggles to the death fill the Perils section. Such artworks enjoyed great popularity in America during the second half of the 19th century. Whether for commerce, sport or sustenance, hunting is fraught with a host of potential perils, including harsh weather, human error, rugged terrain, territorial disputes and wild animals. These works served as both spectacles intended to excite viewers, as well as visual metaphors for man’s attempts to tame the wilderness. As the country moved toward modernity, many Americans romanticized a past that celebrated the danger brave hunters faced in the unforgiving and volatile wilderness.

Depictions of fellowship and camaraderie in the fourth section, Communing in Nature, reveal how outdoor endeavors forged familial bonds and strengthened communities against the backdrop of shifting attitudes toward the natural world. Artists depicted families, pairs and parties engaged in hunting and fishing activities to express their beliefs in these groups as novel communities that would reinvigorate American society. Capturing vital moments of camaraderie and fellowship amongst hunters and fisherman, many artists suggested that these brother- and sisterhoods were communal antidotes to the fracturing of rural societies caused by industrialization and urbanization.

Myth and Metaphor investigates the persistence of mythological associations prevalent to hunting and fishing, the ritual and spiritual aspects of the practice, and the way in which the figure of the hunter in particular became a malleable metaphor in the modern era. The works in this section forge the connections of hunting and fishing imagery in America to traditional myth—from personal mythic narratives of catching the fish of a lifetime, to the subject’s Classical roots, to political and religious allegory. This section reveals that from the earliest cave paintings and modern renderings of the chaste huntress Diana to the coming-of-age ritual aspects of the American Indian hunt and the parallels drawn between their participants and Classical models, the idea of myth and spirit, and even religious symbolism, is central to images of hunting and fishing.

In the final section, Trophies, depictions of spoils of the hunt act as symbols of masculinity, mortality and nostalgia. Artists’ desire to create trophy paintings gave new meaning to trompe l’oeil, or “fool the eye” still lifes. Prized for their cleverness and ability to test the limits of perception, trompe l’oeil still lifes memorialized the hunt for a growing class of sportsmen. Works in this section open onto issues of display and taxidermy, trompe l’oeil gambits and formal innovation.

In conjunction with Wild Spaces, Open Seasons, the Amon Carter presents Caught on Paper, a selection of works on paper from the museum’s collection that echoes the themes of the paintings and sculptures in Wild Spaces. The museum will also feature a concurrent video installation by living artist Hugh Hayden called Hugh the Hunter, which shows that the gentlemanly associations of the hunt persist to the present day and that myth, metaphor, perils and trophies continue to be important representations of hunting and fishing in art.

Risky Business: The Perils and Rewards of Hunting in American Art

Suspense-filled

depictions of close calls, tight spots, and struggles to the death

enjoyed great popularity in American art during the second half of the

nineteenth century. As the country moved full steam ahead toward

modernity, many Americans romanticized a past that held preindustrial

activities in high esteem, including rugged and risky excursions in the

wild. The visual culture that emerged around hunting reflected the

social and economic anxieties and successes of rapidly changing times by

illustrating the harsh environments and dramatic confrontations endured

in pursuit of quarry, whether for commerce, diversion, or sustenance.

The English-born artist Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819–1905) found inspiration in the hard-scrabble life and craggy terrain of New York’s Adirondack Mountains. His paintings perpetuated the archetype of the brave hunter who, through courageous acts, conquered and tamed America’s wilderness. The symbolic implications of such works reflected social anxieties of the time while reinforcing the power of individuals and, in turn, the nation. His painting The Hunter’s Dilemma (Fig. 1), reflects a common storyline in American paintings of the second half of the nineteenth century—the mortal predicament. This theme reflected cultural stresses caused by rapid industrialization—as well as the promises and perils of westward expansion—where the potential rewards were worth the risk of hardship, harm, and possible failure. Potentially sacrificing life and limb to retrieve his kill, the hunter in Tait’s painting has climbed down onto a ledge set halfway up the face of a sheer cliff. Dressed in buckskin, a traditional garb that appears throughout popular culture as the costume associated with such heroic figures as Daniel Boone, the young man confronts—and pursues the challenge of—the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of hoisting his dead quarry to higher ground.

The exhibition catalogue