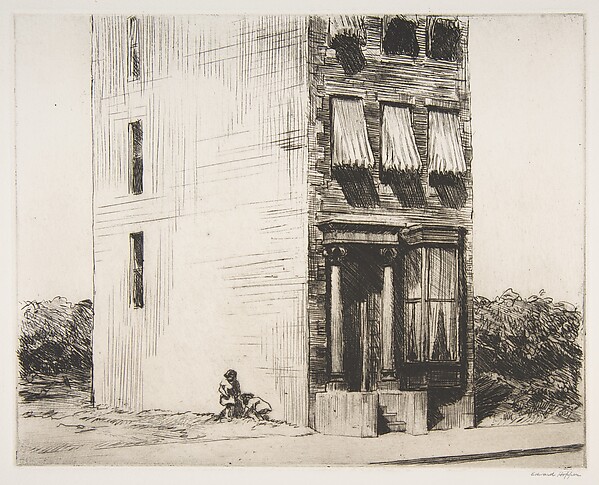

William Merritt Chase’s (1849-1916) Sunlight and Shadow

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916), Sunlight and Shadow, 1884,

oil on canvas, Collection of Joslyn Art Museum, Gift of the Friends of

Art, 1932.4

A brief exchange, perhaps heated, executed quickly to capture a moment.

Sounds like a Twitter tweetstorm, but the subject here is a 19th-century painting once titled

The Tiff, painted

en plein air, a direct rendering out-of-doors of a couple's conversation in a sun-dappled garden.

Executed at the advent of Impressionism, the work's title was later changed to

Sunlight and Shadow by

the artist, reflecting that he thought less of "the tiff" as the

subject than how the light filtered through the branches at that

(Instagrammable?) moment.

One of the

Joslyn Art Museum’s most popular works, and a cornerstone of its American painting collection — William Merritt Chase’s (1849-1916)

Sunlight and Shadow

— has returned to the museum in Omaha following an international tour

that began in the summer of 2016 at The Phillips Collection in

Washington, D.C., as part of the exhibition

William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master.

The exhibition, which marked the centennial of Chase’s death,

explored his role as both an outspoken champion of American art and an

active participant in the international art scene in Europe.

Portraying a couple at afternoon tea in the garden of a home in Zandvoort, Holland,

Sunlight and Shadow

is one of Chase’s earliest forays into plein-air painting. Light

cascades through a canopy of trees, casting dazzling patterns across the

couple — Chase's friend, the painter Robert Blum, and a young woman

reclining in a hammock — captured in what appears to be a fraught

conversation. That the painting was originally called

The Tiff

by the artist may confirm this kind of interpretation, but Chase is

clearly more interested in the naturalism expressed in the title under

which he exhibited it shortly before his death:

Sunlight and Shadow.

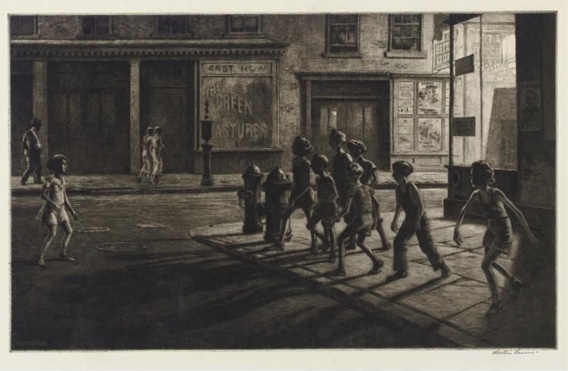

The Domes of the Yosemite by Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt's "The Domes of the Yosemite," 1867

The Domes of the Yosemite, the largest existing painting by Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), made its post-conservation debut at the

Morse Museum

of American Art, in Winter Park, Fla., where it is on view to July

8 through a special loan from the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum in Vermont.

The monumental painting, having just received conservation treatment

in Miami, returns to Vermont in July. Measuring almost 10 feet by 15

feet, the 1867 oil painting has not been shown outside the Athenaeum

since its first installation there in 1873.

“The Domes of the Yosemite," said Morse Museum Director Laurence J.

Ruggiero, “is a virtuoso performance by one of the most beloved painters

of America’s natural beauty—sweeping, sumptuous, dramatic and

luminous.”

“The painting perfectly complements the Morse’s collection of 19th-century American art,” he said.

“With age, the canvas had become weak where it wrapped around the

stretcher, so much so that there was significant distortion in the upper

left corner,” said Athenaeum Director Bob Joly. “Also, the surface was

coated with a synthetic varnish in the 1950s, which becomes harder to

remove the longer it remains. When it returns, The Domes will be

appreciated for its beauty and its great condition.”

Treatment of the work at ArtCare Conservation Studio in Miami, where

it arrived in mid-October, has included repairing the tears around the

perimeter, flattening the distortions, and removing surface grime and

varnish.

“The painting is the most important piece in the Athenaeum’s

collection and a major work of 19th-century landscape painting,” Joly

said. “It is our job to preserve it for the generations to come.”

Bierstadt, a German-American artist, was lauded for grandiose

landscape paintings, particularly those that captured the newly

accessible American West. His work represented the maturation of the

great American landscape tradition, and his painting of the Valley of

the Yosemite in California has been called his crowning achievement.

Originally commissioned for $25,000 for the Connecticut home of

American financier Legrand Lockwood, The Domes was showcased in New York

City, Philadelphia, and Boston before its installation in Lockwood’s

mansion. After Lockwood’s death in 1872, it was purchased by Horace

Fairbanks of the E. and T. Fairbanks Company in St. Johnsbury.

Fairbanks—whose brother, Franklin, was an early investor in Winter Park

land and a charter trustee of Rollins College—founded the Athenaeum in

1871, financed its building, and provided for its library and art

collection. In 1873, he added the art gallery to accommodate The Domes.

Morse joined the Fairbanks Company in 1850, ultimately becoming the

controlling partner in Fairbanks, Morse & Co. headquartered in

Chicago.

“Charles Hosmer Morse’s connection to St. Johnsbury is the reason the

Athenaeum offered the painting for temporary display at the Morse

Museum,” Joly said. “We are delighted to share this national treasure

with the Central Florida community, where Morse’s legacy has meant so

much.”

The Morse Museum is known today as the home of the world’s most

comprehensive collection of works by American designer and artist Louis

Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), including the chapel interior he designed

for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and art and

architectural objects from Tiffany’s celebrated Long Island home,

Laurelton Hall. The museum's holdings also include American art pottery,

late 19th- and early 20th-century American painting, graphics, and

decorative art.

For more information about the Morse, please visit

www.morsemuseum.org.

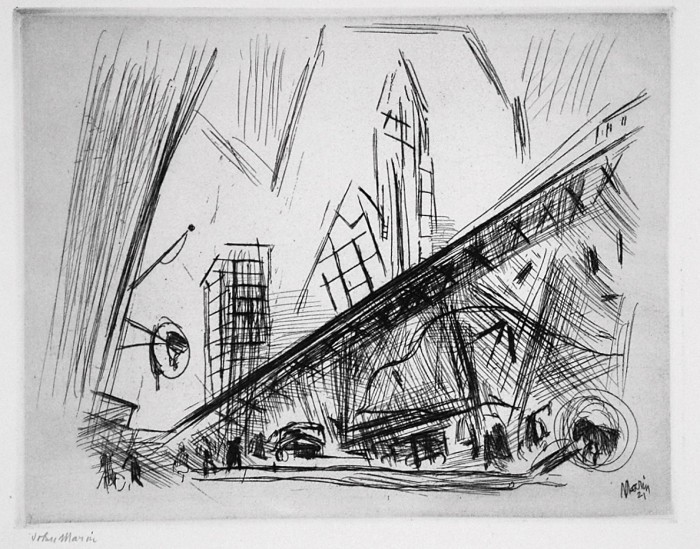

"Artistin (Circus Performers)," Conrad Felixmüller, 1921. Drypoint, 21½ x

13½ in. (54.6 x 34.3 cm). Colby College Museum of Art. The Norma Boom

Marin Collection of German Expressionist Prints, 2017.449. © 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

"Artistin (Circus Performers)," Conrad Felixmüller, 1921. Drypoint, 21½ x

13½ in. (54.6 x 34.3 cm). Colby College Museum of Art. The Norma Boom

Marin Collection of German Expressionist Prints, 2017.449. © 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn