de Young

October 12, 2024 to February 9, 2025

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

March 9 to May 26, 2025

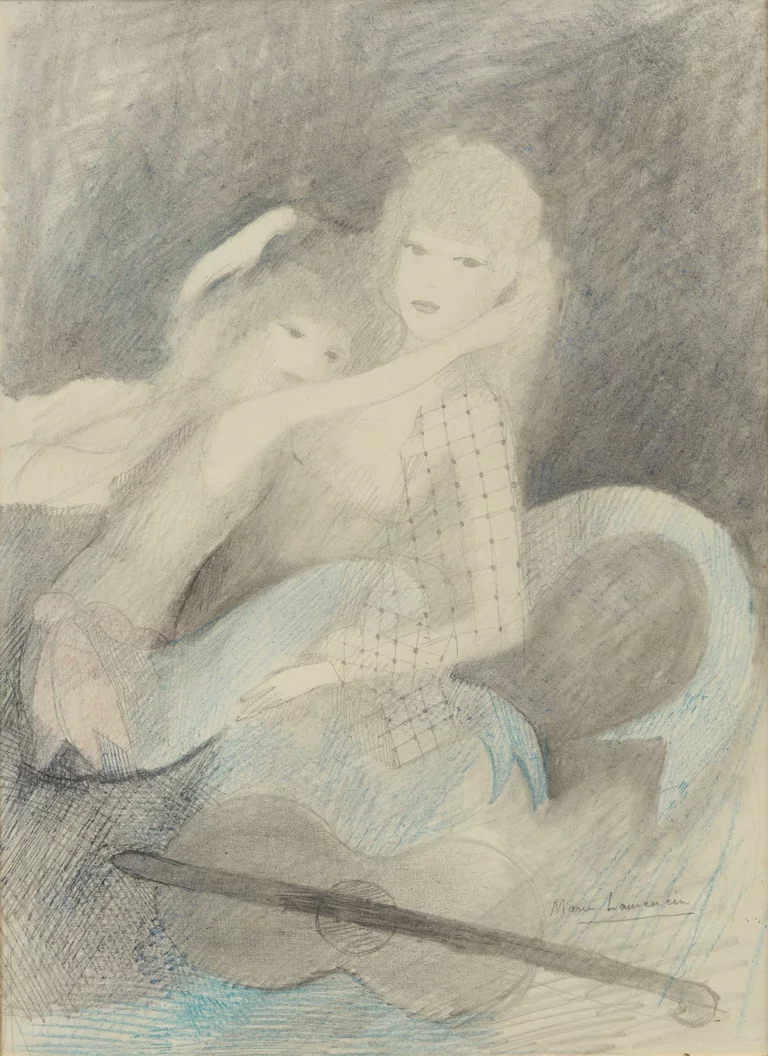

An alluring representation of Lempicka’s multifaceted work, La Tunique rose presents a rich tableau balanced by piercing lines and sumptuous curves, her radiant figure accentuated by dramatic chiaroscuro and the pop of silky color against swells of sensuous skin. Beyond her fastidious attention to line and composition, Lempicka possessed a talent for portraying women in a sexualized yet empowering way. The artist’s appreciation of the female form and its power also recalls the once-scandalous nudes of Modigliani, whose works presented women in full possession of their sexuality, often with knowing and solicitous gazes that shocked audiences and authorities at the time.

Through her liberal and glamorous lifestyle, artist Tamara de Lempicka (1894-1980) has become synonymous with the carefree spirit and opulence of the 1920s. Her paintings, combining a classical figural style with the modern energy of the international avant-garde, have cemented Lempicka as one of Art Deco’s defining painters, with an enduring influence on today’s pop culture landscape. Retrospective Tamara de Lempicka—the first exhibition in the United States dedicated to the artist’s full oeuvre—will reveal a new perspective on her life and design practice. In addition to her celebrated portraits, the more than 150 works on view will also include a number of rarely seen drawings, experimental still lifes from Lempicka’s early Parisian years, melancholic domestic interiors, as well as a selection of Art Deco objects, sculptures and dresses from the Fine Arts Museums’ collection that provide perspective on the artist’s process and historical context. The exhibition is co-curated by Furio Rinaldi and Gioia Mori.

“We are thrilled to present the first major retrospective of Tamara de Lempicka’s work in the United States. As one of the preeminent portrait painters of the Art Deco period, a scholarly consideration of her artistic output for a North American audience is long overdue” said Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “Considering San Francisco’s history as a great Art Deco capital of the world, the exhibition-–aptly presented in close proximity to landmarks of the period such as the Golden Gate Bridge and Coit Tower–adds to our understanding not only of Lempicka’s work specifically, but also this influential art and design period at large.”

Tamara de Lempicka unfolds chronologically in four major chapters that mark the stages in the artist’s life through her changing identity: “Tamara Rosa Hurwitz” (her newly revealed birth name), “Monsieur Łempitzky,” “Tamara de Lempicka,” and “Baroness Kuffner.” The different sections of the exhibition present the evolution of her artistic style and summarize the most prevalent themes of her work. The exhibition includes poignant and experimental still lifes from Lempicka’s early Parisian years, figural works inspired by the Russian avant-gardes, the Cubist aesthetic of her teacher, French cubist painter, André Lhote, as well as her appreciation for the work of Neoclassical painters of the 18th century like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Executed with a polished technique, the portraits on display reflect influential figures in Lempicka’s life, including her muses and lovers (poet Ira Perrot, the model Rafaëla and Marquis Guido Sommi Picenardi), portraits of her daughter, Marie-Christine “Kizette”, and her two husbands, Tadeusz Łempicki and Baron Raoul Kuffner de Dioszegh. Distinguished figures from the dazzling European and American cosmopolitan scenes of the 1920s are also featured prominently, as Lempicka was often tapped by the elite during the peak of her success to paint stately, bold and sometimes intimidating portraits.

“The combination of varied artistic influences in Europe during the interwar period constitute the ingredients for Lempicka’s unique visual language, a captivating and unique blend of classicism and modernism,” explained Gioia Mori, exhibition co-curator, professor of Contemporary Art History and leading Lempicka scholar. “After decades of research, this exhibition constituted the opportunity to investigate Lempicka’s first sojourn in the United States in the spring of 1929. She first arrived in New York and then traveled to Santa Fe and San Francisco. In San Francisco, she exhibited in 1930 at the then-renowned Galerie Beaux Arts. Lempicka’s relationship with San Francisco continued through 1941 when she exhibited a selection of her latest works at Courvoisier Gallery on Geary.”

Research leading to the exhibition has allowed the curators to clarify crucial and unpublished biographical aspects of Lempicka’s life. The artist was born to a Polish family of Jewish descent in 1894 (and not 1898, 1900 or 1902, as she previously claimed), with the birth name Tamara Rosa Hurwitz. She moved to Russia with her family, where she married Tadeusz Łempicki in 1916. Their only daughter, Marie Christine “Kizette,” was born the same year. Despite their divorce in 1929, Lempicka continued to use her first husband’s name to sign her artworks throughout her life.

Following the turmoil of the Russian Revolution in October 1917, Lempicka fled to Paris, where she would arrive in 1919 and remain throughout the 1930s, one of the millions of refugees who dispersed throughout Europe. As an openly bisexual, cosmopolitan polyglot who had lived in various European countries, she thrived in Paris and effortlessly took on the identity and lifestyle of a transgressive, carefree and trendsetting Parisian. At the beginning of her career, Lempicka chose to sign her works using the male declination of her surname, “Lempitzky,” effectively disguising her gender and adding to the confusion surrounding her origin story. However, in later signing her work “Lempitzka” and “Lempicka” she revealed her female identity.

Tamara de Lempicka and Tadeusz Łempicki divorced in 1929, and in 1934 she married Baron Raoul Kuffner de Dioszegh, a Hungarian-Jewish nobleman from present-day Slovakia. In February 1939, Lempicka left Paris for the United States to attend an exhibition organized in New York. This trip saved her from witnessing the tragic Nazi occupation of Poland and Paris in 1939 and 1940. During her time in the United States, Lempicka lived in Beverly Hills and New York City, eventually joining her daughter Kizette (married surname Foxhall) in Houston. Shortly after being rediscovered as an Art Deco icon in the mid-1970s, she died in her home in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in 1980.

Also featured are Lempicka’s paintings of the 1930s and late 1940s, executed upon her departure from Europe in 1939. Many of these melancholic still lives and domestic interiors are defined by a polished pictorial technique and deliberate process that Lempicka sourced from the masters of Italian and Flemish painting.

“The exhibition stems from the Fine Arts Museums’ recent acquisition of a drawing by Lempicka, a portrait of her daughter Kizette, which will be on view to the public for the first time in the exhibition. Reflective of her meticulous academic training in Paris, Lempicka’s drawings reveal both the artist’s outstanding technical refinement as a designer and her breath of visual sources, at the core of her unique style – from Italian Mannerism to the French Neoclassicism, the Russian avant-garde and the innovative graphic language of fashion illustrators like George Barbier, Helen Dryden and Georges Lepape,” shared Furio Rinaldi, exhibition co-curator and curator in charge of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “Beyond celebrating Lempicka’s Art Deco persona, Tamara de Lempicka will reveal the artist’s layered artistic influences, demonstrating how her appreciation and knowledge of European art history informed the deliberate design process behind her memorable paintings.”

The exhibition also includes a special section on the relationship between Lempicka and fashion in the 1920s and 1930s, demonstrated through the works she produced for the German fashion magazine Die Dame - including the famous cover Self-Portrait on a Green Bugatti. This relationship is also demonstrated through garments from the Museums’ collection of costume and textile arts, with clothing produced by pioneering women designers Callot Soeurs, Madeleine Vionnet, and Madame Grès, and characterized by elegance and ease of physical movement as well as a renewed interest in the natural shape of women’s bodies.

Lempicka embodied the independence of a dynamic type of the “New Woman,” capable of fashioning her own personality and path through stylish modes of dress. The haute couture fashions represented in Lempicka’s paintings, such as the Portrait of Ira P. or the Girl in Green, vividly capture the plurality of clothing styles available to women during the interwar era and illustrate Lempicka’s modern beauty, powerful femininity and status among the upper-class Parisians.

Opening at the de Young on October 12 and running through February 9, Tamara de Lempicka is the first scholarly museum retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States, exploring Lempicka’s artistic influences and revealing the process behind works that have become synonymous with Art Deco. After its presentation at the de Young, the exhibition will travel to Houston and be on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, March 9 through May 26, 2025.

With portraits that exude a cool elegance and enigmatic sensuality, Tamara de Lempicka (1894–1980) became one of the leading artists of the Art Deco era as she distilled the glamour and vitality of postwar Paris and the theatrical sheen of Hollywood celebrity. Conceived by Gioia Mori, preeminent scholar of Lempicka’s work, and Furio Rinaldi, curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, this retrospective exhibition—the first major museum survey devoted to the artist in the United States—explores Lempicka’s distinctive style and unconventional life through over 90 paintings and drawings, which range from her first post-Cubist compositions and her coming of age in 1920s Paris, to her most famous nudes and portraits of the 1930s, to the melancholic still lifes and interiors of the 1940s. Following its San Francisco premier in autumn 2024,Tamara de Lempickawill be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from March 9 to May 26, 2025, the second and final venue of the exhibition.

“Tamara de Lempicka took Paris by storm in the 1920s with paintings that united classicism and high modernism to create some of the most defining works of the Art Deco era,” commented Gary Tinterow, director and Margaret Alkek Williams chair of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “Her brilliant portraits and figure studies quickly captured the popular imagination across Europe and the United States, but her career was eclipsed by World War II. Now her work is once again rightly in the spotlight, after being alternately celebrated, ignored, and rediscovered for almost a century. We are enormously pleased to be able to present this thoughtful, considered appraisal, one that will help ensure a lasting appreciation of Lempicka’s singular vision.”

Tamara de Lempicka describes the arc of the artist’s career in the context of her times and against the backdrop of epochal world events. Born Tamara Rosa Hurwitz in Poland in an era of fierce anti-Semitism, she learned at an early age to conceal her Jewish ancestry. In 1916, she married a Polish aristocrat, Tadeusz Lempicki, and the two settled briefly in St. Petersburg before fleeing to Paris in the wake of the Russian Revolution. Faced with the need to earn money, Lempicka determined to become an artist: she first presented her paintings at the Salon d’Automne in 1922 under the name “Monsieur Łempitzky,” and then more forthrightly as “Tamara de Lempicka” as she swiftly moved to the forefront of Parisian café society. Over the following decade, Lempicka’s paintings brought her muses and lovers—including the poet Ira Perrot and the model Rafaëla—vividly to life, while her commissioned portraits captured the dazzling cosmopolitan mood of the era.

Lempicka’s second marriage, to Austro-Hungarian Baron Raoul Kuffner-de Diószegh, granted her the title “Baroness Kuffner,” the name she took with her to the United States in 1939 in advance of the German invasion of Paris. After 1945 Lempicka divided her time between New York, Paris, and Houston where her daughter Kizette had settled. She spent her final years in Cuernavaca, Mexico. By the late 1940s her paintings had fallen out of step with the times, and as her studio practice ebbed, she exhibited infrequently throughout the 1950s and 1960s. However, Lempicka lived to witness a revival of interest in her work following the 1972 landmark exhibition Tamara de Lempicka de 1925 à 1939, mounted by the Galerie du Luxembourg in Paris. Barbra Streisand and Madonna, among other celebrities, acquired and helped popularize her iconic portraits in subsequent years.

In Houston the installation will be complemented by photographs of the artist and selections from the MFAH’s permanent collection of modern design, as well as key additional loans from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, including drawings by Lempicka’s teacher and mentor André Lhote. “Acutely conscious of fashion and design, Tamara de Lempicka also had an inventive eye for detail,” states Alison de Lima Greene, coordinating curator for the exhibition at the MFAH. “Fiercely intelligent and unapologetically ambitious, she clearly understood the power of celebrity, and she took care to present herself after the style of Hollywood stars, staging portrait-photo sessions in her studio while clad in the latest couture. At the same time, her paintings are beautifully crafted, with an assured painterly touch impossible to see in reproduction.”

Exhibition Organization

Tamara de Lempicka is organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in collaboration with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

In addition to major contributions by Furio Rinaldi and Gioia Mori which bring to light hitherto unknown drawings and details of the artist’s biography, the lavishly illustrated catalogue features a preface by Barbra Streisand, a tribute from Françoise Gilot, and essays by Laura L. Camerlengo on “Fashioning the Modern Woman” and by Alison de Lima Greene on Lempicka in America. The exhibition has also benefitted from the archives and generous expertise of the artist’s family, which has graciously cooperated with this project.

IMAGES

Tamara de Lempicka, Young Girl with Gloves (detail), 1930–1931. Oil on board, 24 1/4 x 17 7/8 in. (61.5 x 45.5 cm). Centre Pompidou, Paris, Purchase, 1932, inv. JP557P.2023. Courtesy of Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY

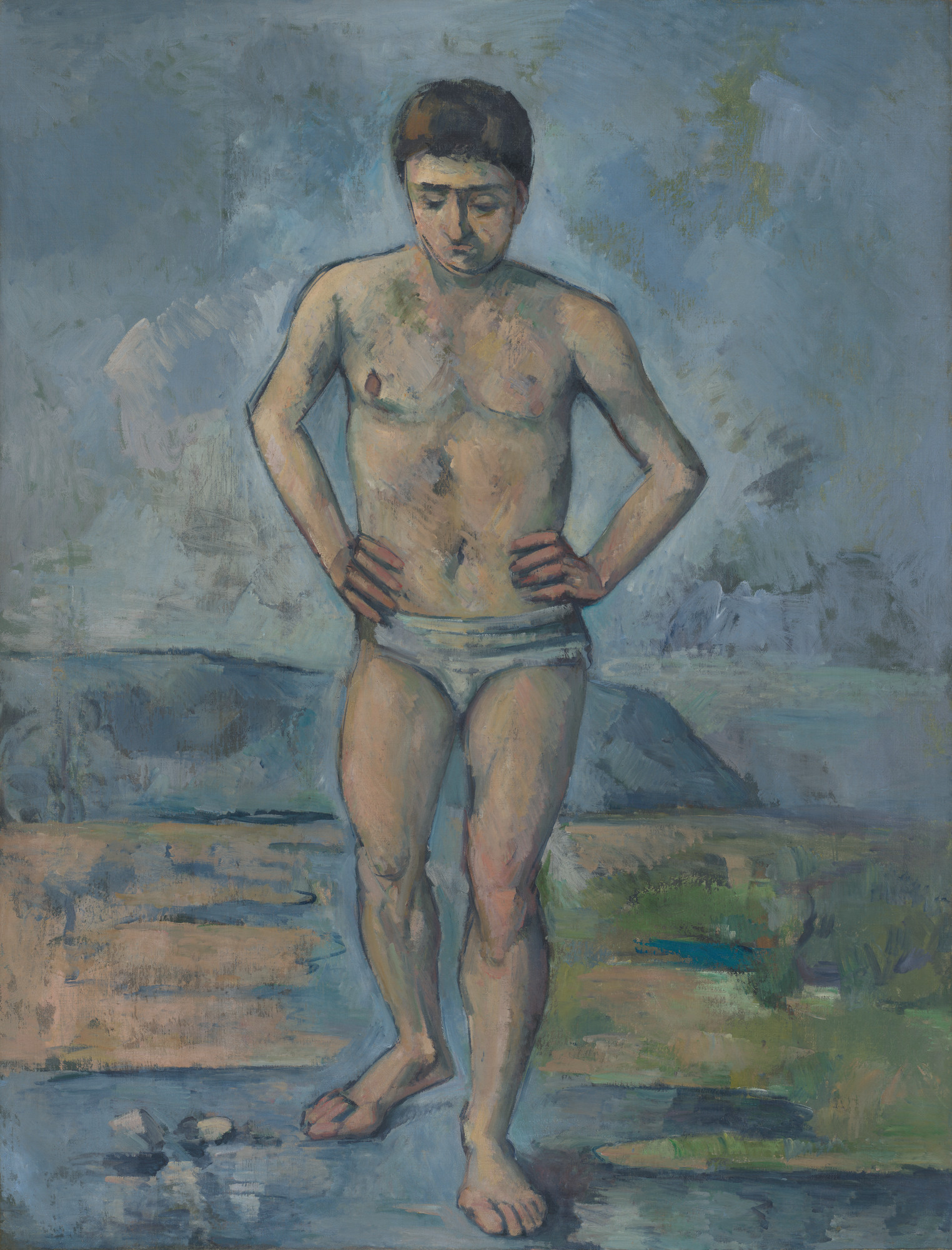

Tamara de Lempicka (1894 - 1980) “Male Nude,” ca. 1924 Oil on canvas, 41 3/8 x 29 1/2 in. (105.1 x 75 cm) Collection of Harvey Fierstein © 2024 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY © 2018 Christie’s Images Limited

Also see:

More Recent Auctions:

Christie's Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale 5 February 2020

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait de Marjorie Ferry 39 x 25 in. (100 x 65 cm.) (1932) £8,000,000-12,000,000 (US$10.4-15.7m)

Portrait de Marjorie Ferry was commissioned in 1932 by the husband of the British-born cabaret star Marjorie Ferry at the height of Lempicka's fame in Paris where she was the most sought-after and celebrated female modernist painter. By 1930 Lempicka had become the première portraitist in demand among both wealthy Europeans and Americans, specifically with those who had an eye for classicised modernism.

Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on 12 November 2019

Depicting one of Tamara de Lempicka’s most famed muses and lovers, Rafaëla, La Tunique rose from 1927 presents a rare example of the artist’s full-length figures (estimate $6/8 million).

https://photos.google.com/share/AF1QipPI5OqV30XZZLXkFGTqtkwMyCnJozuNhkoz1kb58mPlaiXZwoPl5nHDjJb11oysjw?pli=1&key=QU1NRVY5N2tpSV9UclhsekUxbGRyQmZzTWtSeUd3