The King’s Gallery at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh

A design by Leonardo da Vinci for a fantastical dragon costume is one of more than 80 drawings by 57 different artists that are on display as part of the widest-ranging exhibition of Italian Renaissance drawings for over half a century in Scotland.

Drawings by Leonardo, Michelangelo, Titian and more are among 45 works going on display in Scotland for the first time as part of Drawing the Italian Renaissance at The King’s Gallery at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

Following a critically acclaimed showing in London, the exhibition explores the variety and range of drawings in this period, from preparatory studies for paintings and altarpieces to designs for sculpture and elaborate drawings which were made as gifts. Drawings were often discarded after they had served their purpose, with only a small proportion surviving, but the works on display have been carefully preserved in the Royal Collection for centuries, allowing them to be enjoyed almost as vividly as when they were created.

Lauren Porter, curator of the exhibition, said ‘This is a remarkable opportunity to share so many of the Italian Renaissance drawings from the Royal Collection, with over half being shown in Scotland for the first time. As works on paper cannot be permanently displayed for conservation reasons, this exhibition offers a rare opportunity for visitors to view these drawings up close, giving a unique insight into the minds of the great artists who made them.’

Reflecting the continued importance of drawing today, the Gallery is hosting its first artist residency, in collaboration with Edinburgh College of Art. Edinburgh-based artists Phoebe Leach and Dette Allmark, both alumni of the School, will respond to the masterpieces on display by drawing in the Gallery throughout the exhibition. Their creations will form a changing display for visitors, who are encouraged to take inspiration and try drawing themselves, with materials freely available.

A highlight work on display is an example of one of Leonardo’s anatomical studies drawn from a real-life dissection. The double-sided drawing which shows the muscles of a man was created in c.1510–11 and shows his detailed, personal notes in his left-handed ‘mirror-writing’.

Perhaps lesser known are the anatomical studies of Michelangelo, who reportedly conducted human dissections as a young man. On display for the first time in Scotland is his study of a male torso in pen and ink, which was likely drawn from a wax model made by the artist, which shows his ongoing interest in human anatomy later in life. This can also be seen in his highly finished black chalk drawing of the resurrected Christ, with the artist capturing the energy of the muscular figure rising from his tomb.

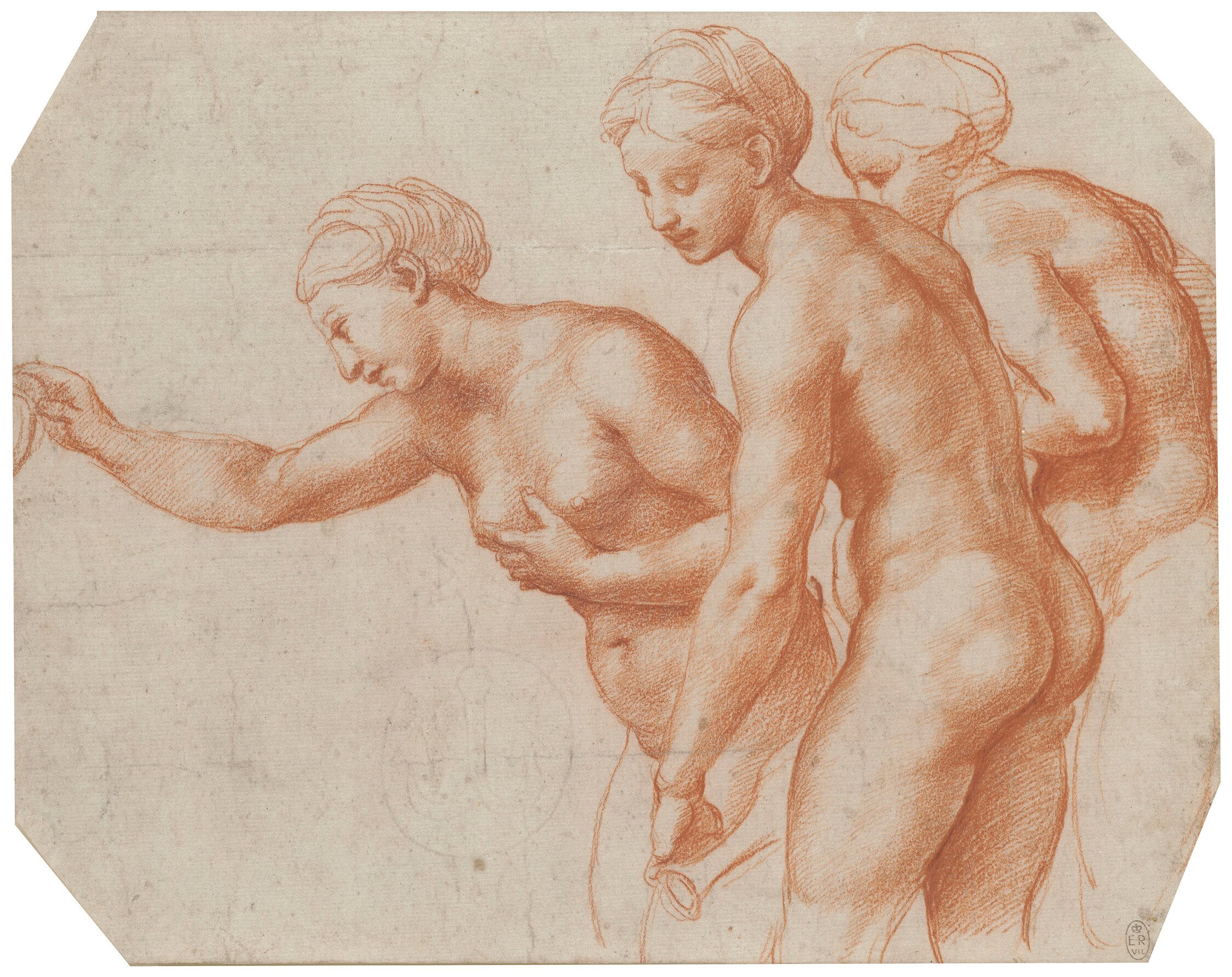

Other striking figure studies on display include two works by Raphael: a vigorous drawing of Hercules slaying the many-headed Hydra, and a red chalk study of The Three Graces that was – unusually for the period – drawn from a nude female model.

Scenes from mythology were common subjects for Italian Renaissance artists and are well-represented in the exhibition. They include drawings by lesser-known artists including Paolo Farinati’s design for a fresco showing the goddesses of fruit and agriculture. The drawing, which has not been on display before in Scotland, is inscribed with instructions for the artist’s assistants on the height of the figures, telling them they should be around three-feet-high but to ‘do it as you fancy when you are on the scaffolding.’

Other highlights on display include a drawing attributed to the Venetian artist Titian of an ostrich, believed to have been drawn from life, and Leonardo’s design for a dragon costume, which appears to house two men, in the manner of a pantomime horse.

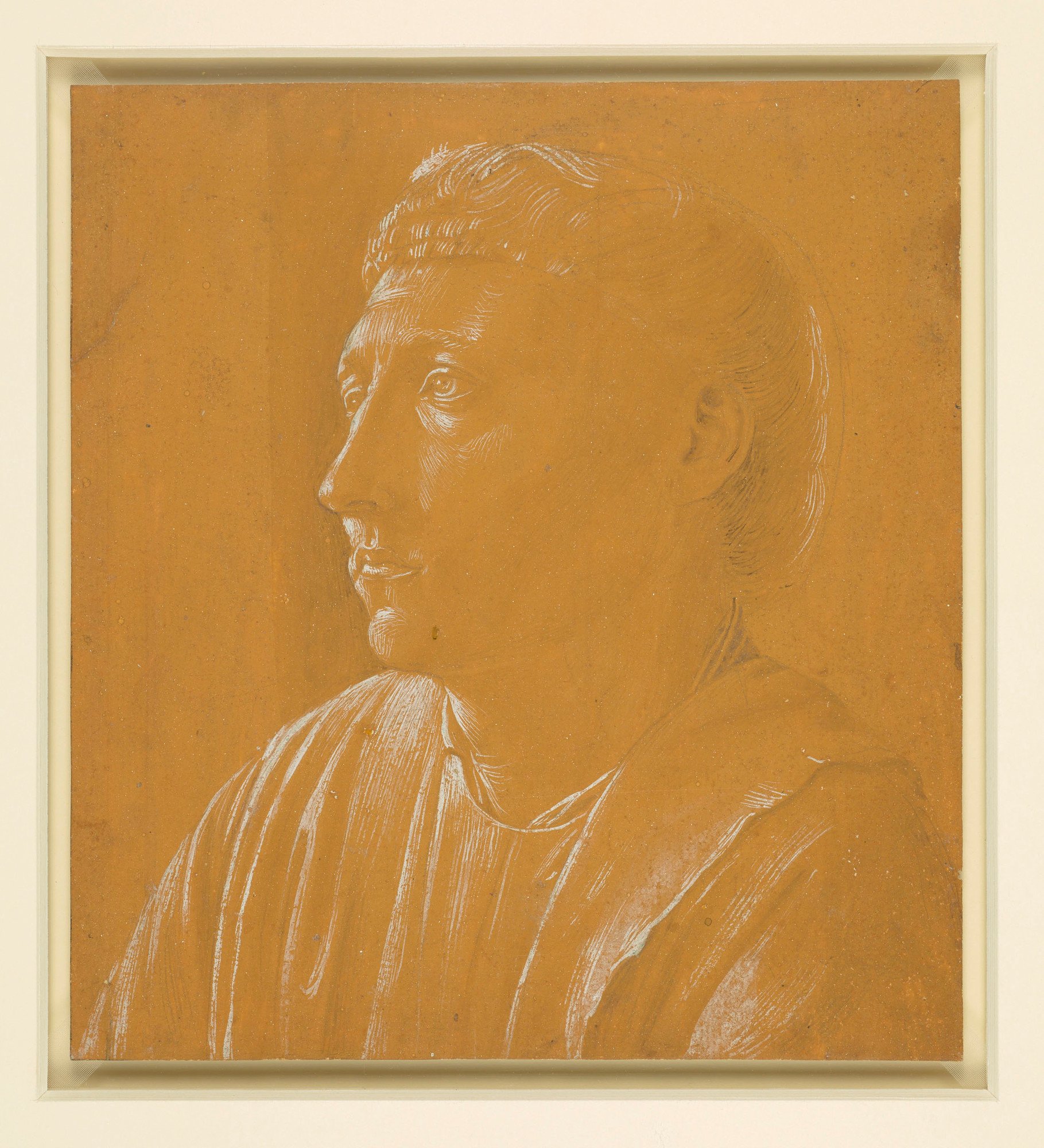

A series of portrait drawings and head studies show the range of subjects, materials, functions and colours of Italian Renaissance drawings. The distorted and tormented face of a grotesque mask sketched by Michelangelo, possibly a design for a sculpture, contrasts with the classical features of Leonardo’s red and black chalk drawing of a curly-haired young man which is displayed nearby, with both works on show for the first time in Scotland.

After almost 120 hours of conservation work by Royal Collection Trust conservators ahead of the London exhibition, Bernardino Campi’s cartoon for an altarpiece of the Virgin and Child is on show for the first time in Scotland. The cartoon, a large-scale drawing made of four pieces of paper joined together, was originally used to transfer the drawing onto a painting’s surface. The conservation work involved painstakingly removing the drawing from its deteriorating canvas backing and supporting sections where the paper had become as delicate as lace.

The Italian Renaissance saw the range and purpose of drawing greatly expand, resulting in some of the finest works of art in any medium. Michelangelo’s meticulous drawing A children’s bacchanal marks a highpoint of Renaissance draughtsmanship and is in perfect condition, allowing us to see Michelangelo’s mastery of the art of drawing.

IMAGES

Leonardo da Vinci, A design for a dragon costume, c.1517–18 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the trunk and leg, c.1510–11 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Anatomical studies of a male torso, c.1520 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Risen Christ, c.1532 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Raphael, Hercules and the Hydra, c.1508 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Raphael, The Three Graces, c.1517-18 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Raphael, The Three Graces, c.1517-18 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Leonardo da Vinci, The head of a youth, c.1510 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Paolo Farinati, The goddesses of fruit and agriculture, and a personification of summer, c.1590 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Michaelangelo Buonarroti, A grotesque head, c.1525–30 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Attributed to Titian, An ostrich, c.1550 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Bernardino Campi, The Virgin and Child, c.1570–80 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Michelangelo Buonarroti, A children’s bacchanal, 1533 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Attributed to Fra Angelico (c. 1400-1455)

Recto: The bust of a cleric. Verso: A group of figures c.1447-50

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475 - 1564)

The Virgin and Child with the young St John c.1532

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

A costume study for a masque c.1517-18

Parmigianino (Parma 1503-Casalmaggiore 1540)

Studies of dogs c.1522-23

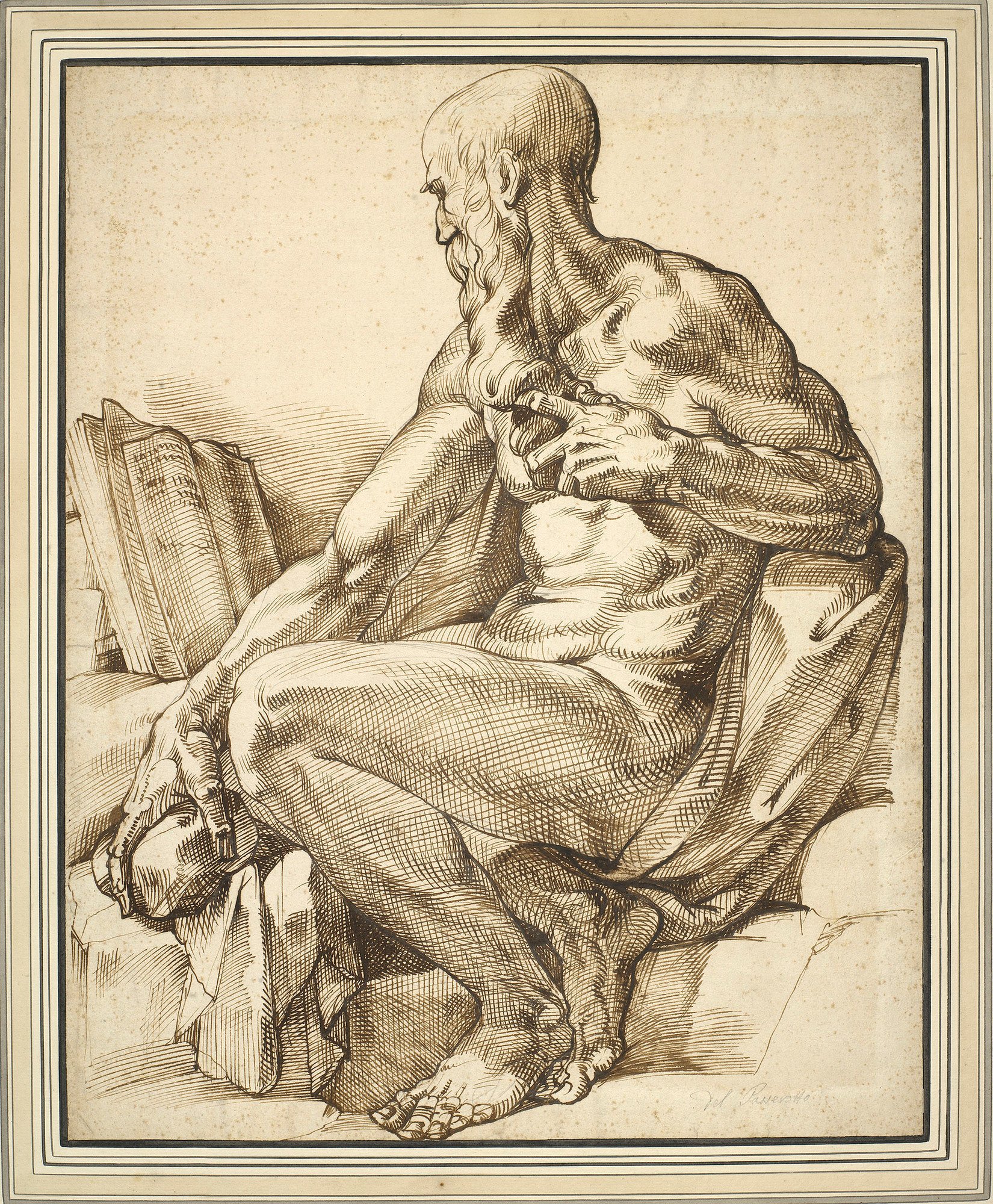

Bartolomeo Passarotti (1529-92)

St Jerome c. 1580

Alessandro Allori (Florence 1535-Florence 1607)

Fortitude, Prudence and Vigilance c.1578