Kunsthaus Zürich

9 March to 8 July 2018

The Kunsthaus

Zürich showcases 56 works of representational painting spanning the years 1890

to 1965. Common to all of them is an objectivity that is also visionary: emerging

on the cusp of modernity, it runs through Böcklin and Vallotton, the ‘ naïve

artists ’ and painters of New Objectivity, to the Surrealism of Dalí and

Magritte.

This new exhibition at the Kunsthaus revisits a form that, like abstraction, was crucial to Classical Modernism: representational art.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN PAINTING

By the mid -19th century, as modern painting begins to take shape, the focus of attention is already shifting from conte nt towards artistic means. Édouard Manet attaches great importance to ‘ peinture’ – the painterly – while Paul Cézanne‘ s ‘taches ’, or patches of colour, aim not to depict the real world but instead to confer reality upon the image itself. This central idea is carried through into the Cubism that Cézanne anticipates. Collection curator Philippe Büttner has assembled works by some twenty artists who adopted an entirely different approach: at once objective and visionary. For these painters the communicative force of ‘ peinture’ is not what matters; rather, they set out to create visual spaces that remain illusionistic . Even so, Arnold Böcklin – the earliest artist represented in the exhibition – is concerned not with realism but with the primacy of imagination. The landscape and scenery of his 1880 work ‘ The Awakening of Spring ’ are, on the face of it, easy to understand and yet dreamlike and visionary, evoking with painterly precision the alternative reality of the mythical.

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTANCE S

In his first major work ‘ La malade ’, painted in Paris in 1892, Félix Vallotton bypasses Impressionism and draws instead on the narrative Dutch interior painting of the 17th century to create a work of meticulously rendered, precise detail. Yet in the psychological dis tances perceptible between his figures, he proposes a suggestively new take on this seemingly traditional painting technique. Later, as a landscape painter, he will turn his cool gaze towards the phantasmagoric hyper -presence of natural phenomena.

Vallotton was also partly responsible for discovering the ‘ naïve’ Henri Rousseau, praising his jungle painting enthusiastically in an 1891 article. Rousseau paints every leaf with precise contours, accumulating individual, neatly catalogued elements and collaging them into a world of hypnotic strangeness. What impresses here is not ‘peinture’ but the increasingly autonomous formal rhythms and scenic patterns marking the transition from the familiar to the unknown. For all its superficial descriptiveness, painting t hus becomes a novel alternative to the realistic depiction of the world.

NAÏVE ART IN THE MODERNIST CANON

The history of naïve art – represented in the exhibition by key works from Henri Rousseau, Camille Bombois, Henri Bauchant and others – was retold a t length in Kunsthaus exhibitions of 1937 and 1975. Their induction into the modernist canon came about largely thanks to the German collector and dealer Wilhelm Uhde (1874 – 1947), who owned one of the Rousseaus in the Kunsthaus collection. New Objectivity also features in the exhibition, exemplifying the return to representation and rejection of the avant -garde after the brutal caesura of the First World War.

And yet – as Niklaus Stoecklin and Adolf Dietrich demonstrate – supposed objectivity often nurtures an estrangement fed by the almost hypnotic concentration of seeing. This is particularly striking in Dietrich, who magically confers an enhanced presence on his simple, rural motifs.

THE CONSCIOUS AND UNCONSCIOUS WORLDS: SURREALISM

The Dadaists and Surrealists offered a very distinct response to the First World War. In their eyes, society and politics had been thoroughly compromised by the conflict; and the Surrealists therefore sought to express worlds of the unconscious. Eschewing convention and repression, they set out to find the uncategorized essence of humanity as it manifested itself in dreams and unfettered creativity.

Some Surrealists, such as Joan Miró, relied heavily on the development of the painterly; others created dreamlike images founded on a carefully constructed legibility: with the precision of an Old Master, Salvador Dalí shone a light into hitherto unmapped recesses of the unconscious, while René Magritte deployed what was, ostensibly, an entirely representational technique but, through a bravura exercise in the avoidance of meaning, took the peaceful coexistence of form and content to absurd lengths in order to re- energize it.

RARELY SEEN, REMARKABLY ALLURING

From Böcklin to

Dalí, from Vallotton to Dietrich, from the precise passion of a Rousseau creating

worlds not seen before to Magritte ‘s marmoreal birds: all share a visionary objectivity

revealed in a selection of works covering a broad spectrum of both motifs and forms.

The exhibition includes 56 paintings of human beings, animal s, landscapes and

plants from the Kunsthaus collection. Over half of them, especially works by

Camille Bombois, André Bauchant , Adolf Dietrich and Niklaus Stoecklin, have

not been exhibited for many years. All exert a remarkable allure, be it through

wonderful self -portraits, hyper -realistic

depictions of nature, or dazzlingly colourful backgrounds that envelop the figures in surreal fashion. They allow us to explore the enormous potential of a modernism that is – or purports to be – representational: a movement that rehabilitates and fundamentally reinvents the essence of things after its temporary banishment by the avant-garde.

depictions of nature, or dazzlingly colourful backgrounds that envelop the figures in surreal fashion. They allow us to explore the enormous potential of a modernism that is – or purports to be – representational: a movement that rehabilitates and fundamentally reinvents the essence of things after its temporary banishment by the avant-garde.

An

accompanying publication (96 pages, 54 colour illustrations, in German language)

with a text by Philippe Büttner contextualizes the reception of representational

art within the history of the Kunsthaus collection.

André Bauchant

Self-Portrait among the Dahlias, 1922

Oil on wood, 94 x 60.5 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, donated by Mrs. Dr. Marguerite Meyer-Mahler and Franz Meyer, 1988

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Self-Portrait among the Dahlias, 1922

Oil on wood, 94 x 60.5 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, donated by Mrs. Dr. Marguerite Meyer-Mahler and Franz Meyer, 1988

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Salvador Dalí

Woman with Head of Roses, 1925

Oil on wood, 35 x 27 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

René Magritte

The Natural Graces, 1964

Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 46.5 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, donated by Walter Haefner, 1993

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Félix Vallotton

High Alps, Glaciers and Snowy Summits, 1919

Oil on canvas, 73 x 100 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, The Gottfried Keller Foundation, Federal Office of Culture, Berne, 1978

Adolf Dietrich

Portrait of the artist’s nephew, 1929

Oil on cardboard, 82.5 x 54.5 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, donated by Dr. Franz Meyer, 1942

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Henri Rousseau

Portrait of Mr. X (Pierre Loti), 1906

Oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, 1940

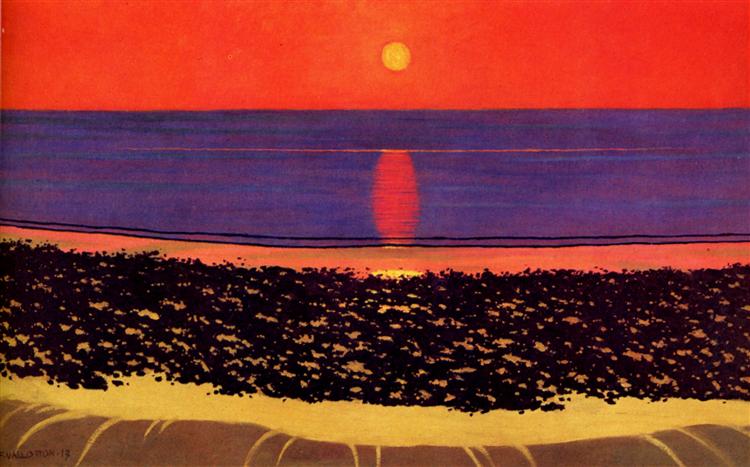

Félix Vallotton

Sunset, Villerville, 1917

Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 97 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde, 1977

Sunset, Villerville, 1917

Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 97 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde, 1977

Camille Bombois

The forest: Winter, c. 1925/1930

Oil on canvas, 102 x 81.5 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, Rolf and Margit Weinberg Foundation, 2003

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Adolf Dietrich

Head of a Girl, 1923

Oil on cardboard, 37 x 28 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Head of a Girl, 1923

Oil on cardboard, 37 x 28 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Élie Lascaux

The Church in Front of the Sea, 1927

Oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, 2015

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

The Church in Front of the Sea, 1927

Oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, 2015

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Niklaus Stoecklin

Portrait of my Wife, 1930

Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm

Kunsthaus Zürich, Dr. H. E. Mayenfisch Collection, 1930

© 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich