Hamiltons Gallery

28 March - 11 May 2018

Hamiltons presents a selection of exceptional and rarely seen Robert Frank prints, including pictures from Frank’s seminal visit in 1953 to a coal-mining village in Wales, along with a selection of prints from his sojourns in London, Paris and America taken during the 1950s and early 60s. Frank’s endeavour to establish a new form of poetic, narrative photography is a common thread throughout these images.

Read "Robert Frank: The Man Who Saw America" published in the New York Times in Summer 2015, written by Nicholas Dawidoff:

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/magazine/robert-franks-america.html

Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of photography – it was Jack Kerouc who first defined Frank as a genius – Frank found fame in the early 1960s with his ground-breaking book The Americans. The series offers a profound insight into the country’s cultural and social conditions and, despite initially perplexing critics due to its unorthodox style, soon became and still remains widely regarded as a pivotal work in 20th century art history.

Its origins can be traced to Frank’s time spent in Paris, and his visit to England and Wales in the 1950s. In Paris, where Frank spent two years in 1949 – 1950, he captured the city’s beauty, viewing its streets as a stage for human activity. As seen in this exhibition, these photographs of Paris taken during that time focus on lonesome, romantic places and people in the city, in particular on the flower sellers. In London, Frank photographed labourers and bankers alike, capturing the city’s spirit following World War II. On one level Frank’s view of London is gloomy, portraying lonely individuals emerging from the nightmare of their recent history, each alienated as they pass people of a different social class. However, his outlook is tempered by capturing the hopeful faces of the children living there. Frank’s camera becomes an extension of his eye, depicting individuals each with their own stories to tell.

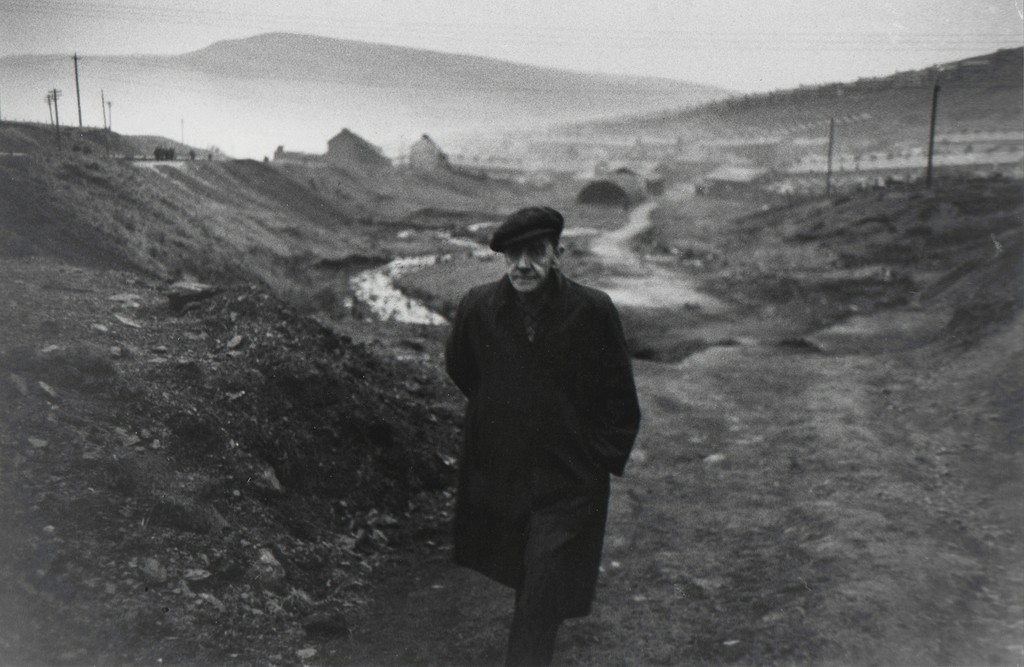

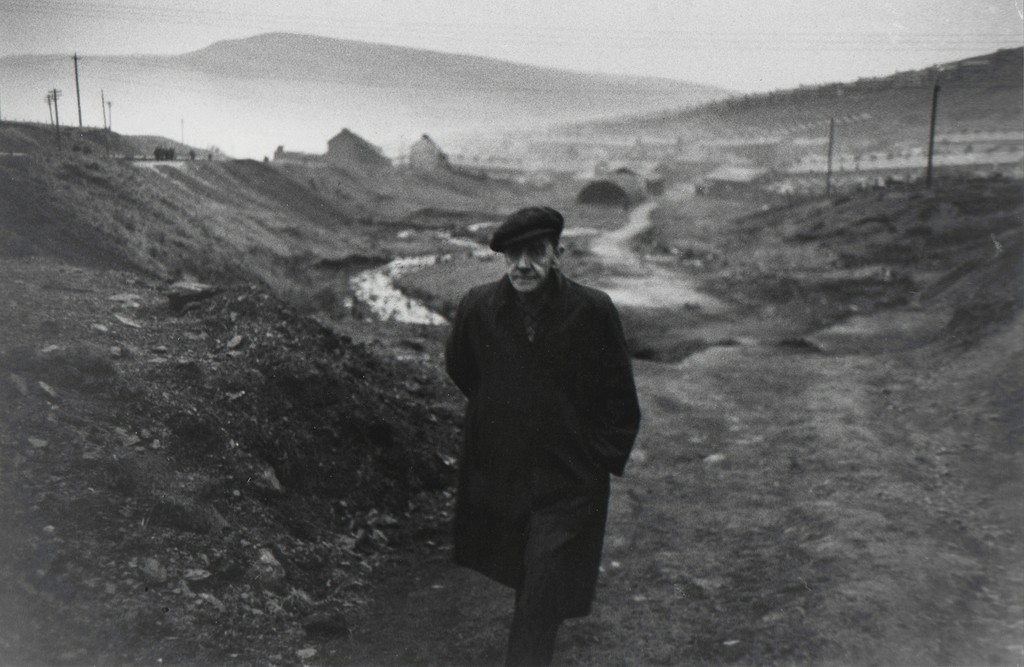

In March 1953, inspired by Richard Llewelyn’s poignant 1939 novel How Green Was My Valley,

Frank’s exploration of coal-stained Caerau in South Wales began. Wales

at the time was isolated from Britain’s financial centre, with a

different language and culture and for the most part inhabited by people

who had lived there all their lives. Frank sought an isolated community

with complex cultural traditions and a history of self–determination,

and he found it in this small town where many people lived in

impoverished conditions. Frank chose to create a photographic story

focused on 53-year-old Ben James, who had worked as a miner since the

age of 14, and lived with his family in a house with no running water.

Frank was there at the start of a time of transition in the lives of the

miners, when the rebuilding of the economy after the Second World War

meant mines were being modernised and working conditions were to slowly

improve. With permission from the Coal Board and the men themselves to

follow and document their daily lives, Frank created a narrative story

about James and his family that could be organised as a day in the

miner’s life. The emotional complexity with which he treated his subject

set a precedent for Frank’s later work, when he would go on to treat

all his subjects with a similar poetic sensibility. When the photographs

of James were first published in the 1955 issue of U.S. Camera Annual, Frank confessed “I

could have followed a livelier and perhaps more colourful Welsh miner

but I’m happy I decided to portray Ben James. When I said farewell to

him I realised that no future story on any Welsh miner will look as this

one does. I’m sure the new generation is essentially the same but I

wonder if not having such hardships will make it easier for them.”

Having set out to document the miners’ lives during this transitional

period, Frank had ended up revealing their humanity from within. Unlike

much of the work that picture magazines were publishing at the time,

Frank’s documentation of Wales expressed more emotion and delved deeper

into people’s inner lives, effectively breaking the rules of documentary

photography at the time.

On 27 May 1953, just two months after Frank returned from Wales to USA, Edward Steichen’s Postwar European Photography exhibition opened at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and 22 of Frank’s photographs were shown, most taken in London and Wales. The images of bankers, beggars and miners filled one large wall, floor to ceiling. Within a matter of months, many of the same subjects would capture Frank’s attention in America and he would use the same methods he had refined and developed in Paris, London and Wales in the 1950s. Described by Lou Reed as “the great democratic”, Frank’s search for equality in Wales set the tone for the seminal pictures that became The Americans.

Robert Frank was born in 1924 in Zurich, Switzerland. From 1941 Frank embarked on a series of apprenticeships as a photographer’s assistant in his home country. Moving to New York in 1947, Frank was soon hired by Alexey Brodovtich as a fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, which bought with it opportunity to travel. The United States made such an impression on Frank that, after receiving his first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955, Frank embarked on his two-year trip across America. In 1959 Frank began making films and in 1972, documented the Rolling Stones on tour which is today probably his most well know film. Frank’s photography and films have been the subject of exhibitions worldwide since Edward Steichen first included Frank’s photographs in the 1950 group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Frank was given his first solo show by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1961 and others soon followed. More recent exhibitions include “Robert Frank: Storylines” at Tate Modern, London in 2004, “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans” which opened at National Gallery of Art, Washington in 2009 and then travelled to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Frank has received many honours and his work is now held in numerous collections worldwide including Art Institute of Chicago; Maison European de la Photographie, Paris, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Tate Modern, London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In 1990 the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., established the Robert Frank Collection. Numerous monographs of Frank’s work exist, including The Americans (1958, 1959), New York to Nova Scotia (1986), London/Wales (2003), to name a few. Robert Frank now lives in New York City.

28 March - 11 May 2018

Hamiltons presents a selection of exceptional and rarely seen Robert Frank prints, including pictures from Frank’s seminal visit in 1953 to a coal-mining village in Wales, along with a selection of prints from his sojourns in London, Paris and America taken during the 1950s and early 60s. Frank’s endeavour to establish a new form of poetic, narrative photography is a common thread throughout these images.

Read "Robert Frank: The Man Who Saw America" published in the New York Times in Summer 2015, written by Nicholas Dawidoff:

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/magazine/robert-franks-america.html

Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of photography – it was Jack Kerouc who first defined Frank as a genius – Frank found fame in the early 1960s with his ground-breaking book The Americans. The series offers a profound insight into the country’s cultural and social conditions and, despite initially perplexing critics due to its unorthodox style, soon became and still remains widely regarded as a pivotal work in 20th century art history.

Tusuque, N.M., 1955, printed 1978

© Robert Frank

© Robert Frank

Its origins can be traced to Frank’s time spent in Paris, and his visit to England and Wales in the 1950s. In Paris, where Frank spent two years in 1949 – 1950, he captured the city’s beauty, viewing its streets as a stage for human activity. As seen in this exhibition, these photographs of Paris taken during that time focus on lonesome, romantic places and people in the city, in particular on the flower sellers. In London, Frank photographed labourers and bankers alike, capturing the city’s spirit following World War II. On one level Frank’s view of London is gloomy, portraying lonely individuals emerging from the nightmare of their recent history, each alienated as they pass people of a different social class. However, his outlook is tempered by capturing the hopeful faces of the children living there. Frank’s camera becomes an extension of his eye, depicting individuals each with their own stories to tell.

London, 1951

© Robert Frank

© Robert Frank

On 27 May 1953, just two months after Frank returned from Wales to USA, Edward Steichen’s Postwar European Photography exhibition opened at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and 22 of Frank’s photographs were shown, most taken in London and Wales. The images of bankers, beggars and miners filled one large wall, floor to ceiling. Within a matter of months, many of the same subjects would capture Frank’s attention in America and he would use the same methods he had refined and developed in Paris, London and Wales in the 1950s. Described by Lou Reed as “the great democratic”, Frank’s search for equality in Wales set the tone for the seminal pictures that became The Americans.

Robert Frank was born in 1924 in Zurich, Switzerland. From 1941 Frank embarked on a series of apprenticeships as a photographer’s assistant in his home country. Moving to New York in 1947, Frank was soon hired by Alexey Brodovtich as a fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, which bought with it opportunity to travel. The United States made such an impression on Frank that, after receiving his first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955, Frank embarked on his two-year trip across America. In 1959 Frank began making films and in 1972, documented the Rolling Stones on tour which is today probably his most well know film. Frank’s photography and films have been the subject of exhibitions worldwide since Edward Steichen first included Frank’s photographs in the 1950 group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Frank was given his first solo show by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1961 and others soon followed. More recent exhibitions include “Robert Frank: Storylines” at Tate Modern, London in 2004, “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans” which opened at National Gallery of Art, Washington in 2009 and then travelled to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Frank has received many honours and his work is now held in numerous collections worldwide including Art Institute of Chicago; Maison European de la Photographie, Paris, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Tate Modern, London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In 1990 the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., established the Robert Frank Collection. Numerous monographs of Frank’s work exist, including The Americans (1958, 1959), New York to Nova Scotia (1986), London/Wales (2003), to name a few. Robert Frank now lives in New York City.