Paris - On March 25, Christie's is proud to present at auction a group of thirty masterpieces from the collection of Arthur Georges Veil-Picard. Rarely exhibited, this collection—whose works are often known only through black-and-white reproductions—remains among the most mysterious and coveted. Featuring works by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Hubert Robert, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, and Marie-Suzanne Roslin, the sale brings together the greatest names in 18th-century French painting and could, on its own, embody this golden age of art history in France. A true labor of love for the 18th century, the collection perfectly illustrates the joviality, sense of pleasure, and freedom so characteristic of the period. Estimated at €5 to €8 million, this exceptional ensemble represents a long-awaited event for collectors in search of masterpieces.

Treasures of painting and drawing: Among Veil-Picard's favorite artists, Fragonard best reflects the collector's jovial character—he owned up to sixteen of his works, five of which are included in the sale. The centerpiece, The Happy Family, perfectly illustrates the “Fragonard style” (€1,500,000–2,000,000). Painted in the 1770s, after his Italian journey that liberated his manner, this work showcases Fragonard's lively, spontaneous brushwork. Its tender scene is enhanced by the voluptuousness of a deliberately playful composition. Of the various versions of the work, the one offered here is considered by scholars to be the first and most representative of Fragonard's palette. Two other versions remain in private collections, and a preparatory study is held at the André Malraux Museum in Le Havre.

Prestigious provenances: The same lightness is found in a delightful portrait, The Little Coquette, also known as The Peeping Girl (€400,000–600,000). This mischievous, tilted face offers the quintessence of Fragonard's art: a painting of pleasure and spontaneity. Beyond its aesthetic and expressive qualities, it boasts a prestigious provenance, having belonged to Hippolyte Walferdin, a great admirer of 18th-century art, and later to Count de Pourtalès—collectors among the most enlightened of their time, still celebrated today. A charming, large wash drawing, Woman with a Dove, also came from Walferdin's collection before being acquired by the Rothschild family (€200,000–300,000).

Interior scenes: Intimate, confidential scenes remain highly prized by lovers of 18th-century painting. Works by Hubert Robert, Madame Geoffrin's Luncheon and An Artist Presents a Portrait to Madame Geoffrin, perfectly exemplify this taste. Famous for her salon that gathered Enlightenment scholars and artists, Madame Geoffrin embodies the spirit of her century. These two paintings, depicting her in her drawing room and bedroom, brilliantly showcase Robert's talent for capturing the atmosphere of his time. They are also the last works commissioned by this celebrated patron (estimate on request).

Major rediscovery: Among the twenty drawings in the collection, a large sheet in red chalk and black stone by Antoine Watteau stands out as a major rediscovery in the artist's corpus. Illustrated in black and white in the 1996 catalogue raisonné of Watteau's drawings, it was described there as “from an inaccessible private collection.” Reminiscent of the celebrated Pierrot in the Louvre, this Actor Holding a Guitar Under His Arm has never been exhibited publicly (€600,000–800,000).

A remarkable and joyful drawing by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin offers a vivid example of his talent as a chronicler of Parisian life. While female nudes were forbidden at the Academy, the artist depicts a painter and his model in the intimacy of the studio (The Private Academy, €150,000–200,000).

A pastel by Marie-Suzanne Roslin, one of the rare female academicians of the Enlightenment, presents a delicate portrait of Madame Hubert Robert, née Anne-Gabrielle Soos (€70,000–100,000).

Finally, in a more historical vein, the collection also includes a pair of drawings dated 1783 by Jean-Michel Moreau, illustrating festivities held in honor of the Dauphin's birth by the royal couple at the Hôtel de Ville (€300,000–500,000) and at the Palais Royal (€70,000–100,000).

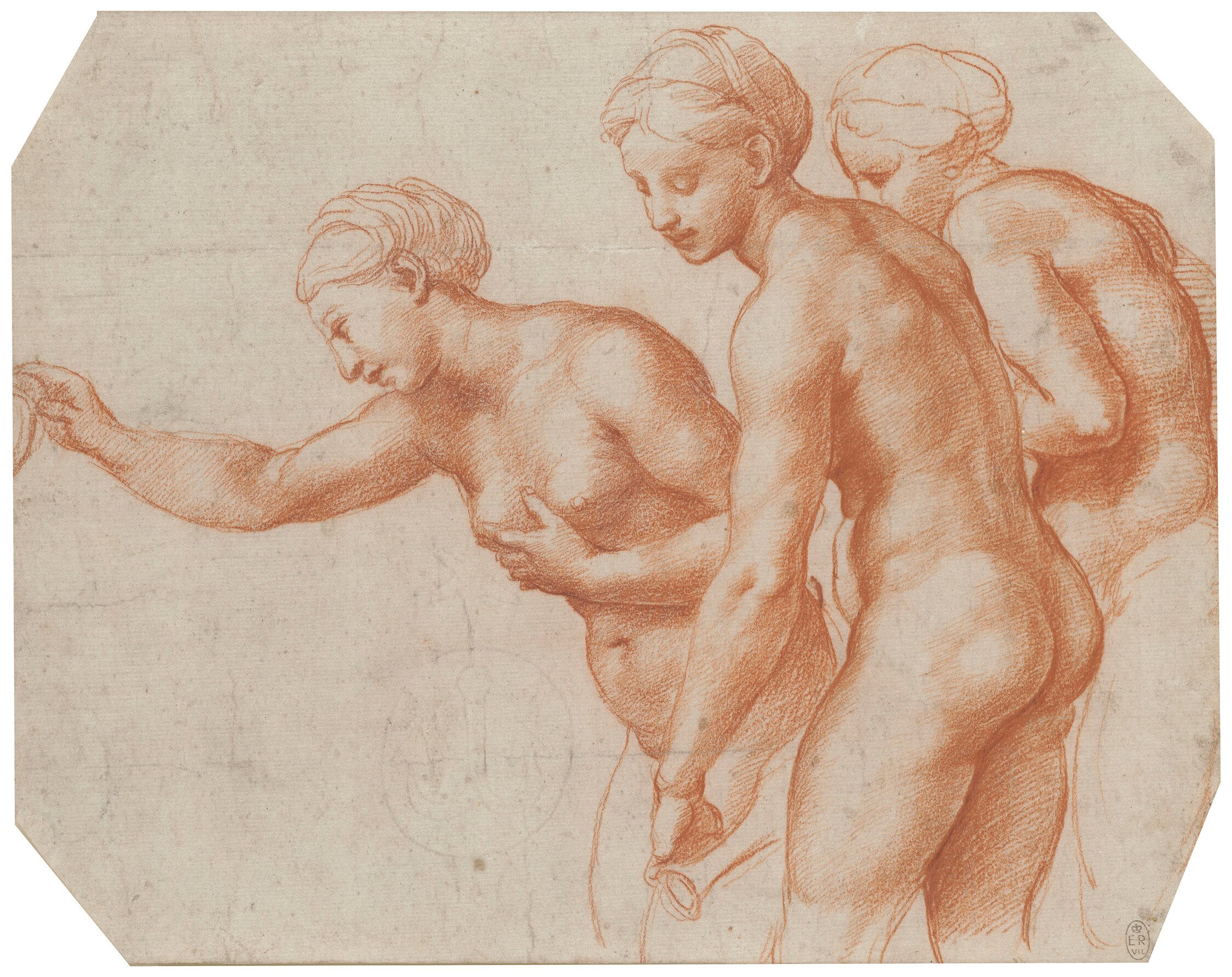

Raphael, The Three Graces, c.1517-18 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Raphael, The Three Graces, c.1517-18 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust