The Albertina (Vienna) presented an exhibition 9 November 2011 – 26 February 2012, an extensive tribute to René Magritte, one of the most renowned and popular artists of the 20th century. Some 250 exhibits from all over the world, including 150 important paintings and works on paper, covered every creative phase of the Belgian Surrealist’s career. More than 90 lenders contributed to this great retrospective, thus enabling the Albertina to present every single one of Magritte’s masterpieces.

Works such as

The Menaced Assassin,

The Menaced Assassin,

The Secret Player,

The Gigantic Days,

Time Transfixed,

.jpg)

The Eternal Evidence,

Golconda

and The Empire of Light

represent Magritte as a main exponent of Surrealism – undoubtedly the most prominent and memorable one next to Dalí. Magritte’s works are not only popular but also have a great intellectual appeal and continue to fascinate present-day viewers due to their enigmatic and mysterious nature.

Magritte was primarily a painter of ideas, an artist of visible thoughts rather than of subject matter. His anti-modernist objectivity, juxtaposed to the avant-garde, may not have enriched art history in terms of form, but did all the more so in terms of motif. In his almost anti-formalist oeuvre he dealt with the material world in a provocative and confusingly open manner. All the objects he painted were clearly recognizable, belonging to the banal, everyday sphere. But when Magritte presented them according to his poetic logic, in an order that cast a completely different light on them and gave them an entirely new power, their meaning began to waver. The recognition of the motifs collided with the mystery of the combination: Magritte brought together things that did not belong together. The artist exposed the viewer’s perception and usual way of seeing as tacit consent and convention, turning the causality of our world view upside down with the depiction of inexplicable metamorphoses, the reversal of the world, the transformation of proportions and surrealistic combinations.

Interior and exterior spaces are connected in a deceptive manner, day and night collide, objects and human bodies merge into one another, and the more distinctly we recognize each object, the more enigmatic the mystery of reality becomes.

Magritte’s paintings draw their generally gloomy atmosphere from the cold and unemotionally staged aesthetics of the depicted subject. Bourgeois orderliness and an ambience of old-fashioned cleanliness turn each space into an eerie crime scene, regardless of whether a murder actually took place or not.

In his extensive oeuvre, comprising paintings, drawings, objects, photographs and short films, Magritte employed a limited number of carefully chosen motifs, reusing them in ever-new combinations to create a complex, surreal world of images. The green apple, the pipe, the man with the bowler hat, the egg, the rock, the curtain, and the sea are some of the elements Magritte repeatedly took up again. They stand for continuity in his creative work and have become the artist’s trademark.

Reflected in almost all of his works, Magritte’s exceptionally eloquent wit is legendary. He pits the symbol against the symbolic, while the occupation with language and parlance generally occupy a prominent position. In his paintings Magritte was influenced by the philosophical theories of the early 20th century, dealing with issues regarding the concurrence of our perceptions, their verbal description and the actual appearance of reality. He was also striving for analogies of an idea, its image and its actual existence, such as in his famous painting

The Treachery of Images

The Treachery of Images where he wrote beneath the depiction of a pipe: “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”).

Magritte’s paintings not only influenced the abstract artistic tendencies of the early 20th century but also Conceptual art and Pop art of the 1960s as well as the analytical approach in contemporary art. In addition, advertising and video clips have been based for decades on the formal principles characteristic of Magritte.

With the additional presentation of the artist’s early commercial art, his photographic experiments and his late, bizarrely absurd short films, the exhibition in the Albertina covers all aspects and phases of Magritte’s creative activity, thus drawing the first comprehensive picture of his complex Surrealist method as well as the continuity of recurring motif groups. As yet another highlight the exhibition provides a profound look into Magritte’s life and working method with extensive photo and film footage as well as original documents.

In thirteen chapters, the exhibition retraced the chronological and content-related developments in his art: starting with the classical Surrealist paintings from the 1920s and 1930s, based on the principle of film and collage, and the autobiographically tinted works in which he dealt, among other things, with his mother’s suicide, to the experimental phases of the post-war period, defined by Magritte as “Surrealism in full sunlight” and his période vache (“cow period”), and concluding with his late work, featuring the mysterious day-and-night paintings of the famous

Empire of Light series

and the “anonymous portraits” of men wearing bowler hats.

The exhibition in the Albertina was not the first presentation of the great Belgian Surrealist’s work in Vienna. The wealth of ideas and omnipresent mystery of his works, however, almost call for a repeated examination of his artistic activity to discover hitherto neglected aspects and thus sharpen our view of his work and our reality. This is made possible thanks to the generous loan of artworks from the most important museums of modern art, including the Kunsthaus Zürich, the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique (Magritte Museum), Brussels, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, The Menil Collection, Houston, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, as well as from prestigious private collections from all over the world. With

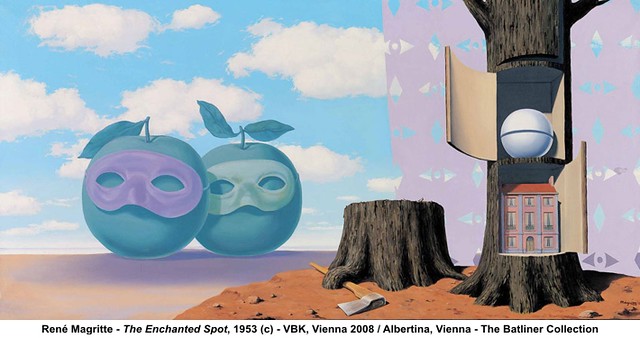

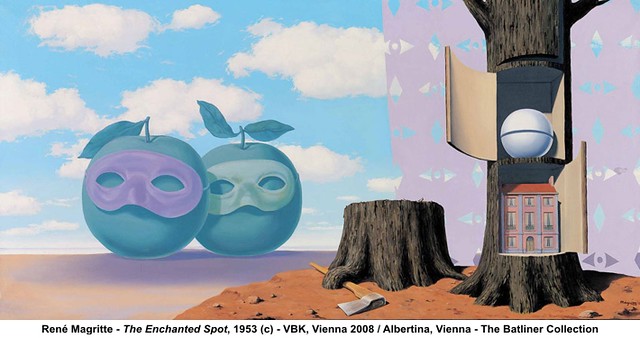

The Enchanted Spot

The Enchanted Spot (1953) the Albertina is in the possession of a major work from the artist’s late period. The René Magritte retrospective is part of a current special focus program on Surrealist art, introduced by the Albertina in 2008 with an exhibition dedicated to Max Ernst’s Surrealistic novel in collage Une semaine de bonté (“A Week of Kindness”), and will be continued with a Max Ernst retrospective scheduled for 2013 as well as with the presentation of Surrealist graphic art from the renowned Gilbert and Lena Kaplan Collection, New York, shown parallel to the René Magritte retrospective.

Wall Texts

THE MAGIC MIRROR

“The peculiar encounter of things may become a revelation: the certainty that there are facts we cannot see.” René Magritte

Magritte was systematically in search of an “overwhelmingly poetical effect” to reveal the world’s mystery. In 1925 he met the writer and philosopher Paul Nougé, who, from 1926 on, headed the “Belgian Surrealists”. In the years to come, Magritte based his investigations on Nougé’s recognition “that certain objects, when taken by themselves, are robbed of an unusual emotional meaning, whereas they retain this very meaning in a context of distortion.” Accordingly, Magritte expanded his method of generating the experience of shock through the juxtaposition of opposites, but also through the unexpected encounter of things similar. At the same time he took up his play with man's anonymity. He painted faceless figures or such rendered as rigid dolls, or reduced them to torsos deprived of identity.

“PAINTED COLLAGES”

Between 1925 and 1927, Magritte, under the impact of Max Ernst’s collages, produced some thirty papiers collés, using newspaper clippings and sheet music. The representation of reality by means of “found materials” was a preferred “method” of the Surrealists when working along the principle of free association.

In an attempt to leave all tradition behind, art was freed from its common materials, such as brushes and paints: collages, photomontages, and found objects resulted in new pictorial realities conveying ambiguous messages.

Through the fragmentation, juxtaposition, and overlapping of objects, Magritte, in his painted œuvre, created compositions that Max Ernst once referred to as “collages painted by hand”. Before his move to Paris in October 1927, gigantic patterns simulating cut paper and hovering in staged scenarios started to appear in Magritte’s paintings. Simultaneously, he employed irritating trompe- l’œil effects.

WORDS AND IMAGES

“Everything tends to make one think that there is little relation between an object and that which represents it.” René Magritte

When in Paris between 1928 and 1930, Magritte frequented the circles around the Surrealists André Breton, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and Joan Miró. Under the spell of their genre-crossing art and the amalgamation of painting and poetry, he did some forty “text-image paintings” in which he analyzed the relationship between a real object, its image, and its name. Magritte challenged the common idea that a realistically painted object is equal to the object as such: each and every image is only an abstraction of reality. It is simply a sign, just as words and language concepts.

In 1929 Magritte conceived his famous pictorial idea of The Treachery of Images or Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This Is Not a Pipe): this pipe, however realistically rendered it may be, cannot be smoked. So what intrinsic relationship is there between the real object and its pictorial representation?

In his treatise Les Mots et les images (Words and Images) Magritte comments on the relationship between the two. The artist undermines the conventional relations between words, images, and objects, looking for new associations between image and text, thus unmasking our standard labels as mere conventions.

COLLAGES & DRAWINGS 1925–1962

“Scissors, paste, images, and genius in effect superseded brushes, paints, models, style, sensibility, and that famous sincerity demanded of artists.” René Magritte

This room assembles works that served Magritte to develop his pictorial inventions: collages, drawings, letters, and postcards. Magritte, who had first intensively dealt with collage during his early Surrealist phase, returned to it once more in 1959. In his lecture La Ligne de vie (The Line of Life, 1938) he writes, under the influence of the collages by Max Ernst, “that one can easily dispense with everything that gave traditional painting its prestige”. The technique of collage enables an artist to create visual worlds fathoming the fine line between the realism of photography or illustration and the free invention of a pictorial idea. Magritte rejected the Surrealist concept of drawing as an automatic and unconscious process: “I cannot paint until I have the complete picture in my mind.”

Magritte also outlined new pictorial ideas, short stories, or film scripts in his letters to friends, colleagues, thinkers, and collectors, discussing with them possible titles for his works. The collection of postcards attests to his interest in reproducible works. Time and again he appropriated extant images for his works: illustrations from encyclopaedias, novels, and comic books, as well as photographs and films.

THE MENACED ASSASSIN

Magritte’s fascination for detective stories like the Fantômas pulp fiction series, which appeared between 1911 and 1913, corresponded with the Surrealists’ interest in psychological abysses and in everything that contradicted civic order: crimes were regarded as anarchical acts, and the deeds of villains were celebrated as free of rules and constraints.

Fantômas is an unscrupulous criminal and at the same time a gentleman: a phantom whose cunning inventiveness confounds his opponents with unsolvable problems. As a master of disguise, he takes on various identities and commits crimes purely for the delight he takes in violating the law. Magritte’s interest in Fantômas becomes most distinctly evident in his making reference to the first book cover of the series. As is typical of the repertoire of crime literature, lifeless bodies, terrified gazes and postures, as well as covered or masked faces, populate his works.

In 1913/14, Louis Feuillade adapted the novels for the cinema. Magritte, who had been fascinated by film even as a child, referred to a shot from the silent movie Le Mort qui tue for his composition of the painting The Menaced Assassin (1927). In a scene that is both charged with tension and completely paralyzed, he retains a narrative aspect. Even the pale corpse does not interfere with the magical, dreamlike silence.

Magritte shared his enthusiasm for the possibilities of film with the Surrealists: in its illusionary portrayal of the real and the coexistence of the familiar and the fantastic, the logic of film connects to the logic of dreams.

A FEELING OF REALITY

AAfter realizing that it was impossible for him to grasp the mystery of reality through feelings, Magritte dealt with the visible world. He painted realistically, renouncing individual painterly expression and constructing traditional perspectival compositions in order to raise his absurd pictorial inventions to a seemingly objective level.

The veiling and unveiling of things hidden is a recurring leitmotif in his œuvre. Curtains, picture frames, window openings, and easels are elements which he employed to stage his “picture-within- the-picture” compositions. His ideas of “invisible visibility” and of the picture as “thought made visible” formed the basis of such works.

“We are surrounded by curtains”, Magritte writes. “We only perceive the world behind a curtain of semblance. At the same time, an object needs to be covered in order to be recognized at all.” Magritte painted clouds superimposed on such unlikely objects as a flag or Napoleon’s death mask. He painted pictures as windows or incorporated canvases into his paintings that function as vistas of the real world. Through this overlapping of inside and outside and of reality and illusion, he questions our concept of reality, thus joining the age-old debate on the idea of the picture as a window to reality.

In such works as The Human Condition, the artist devoted himself to this problem by covering parts of the painted image – the view out of a window – with an easel and simultaneously rendering the concealed part on a canvas placed on this easel: “This is how we see the world. We see it as being outside ourselves even though it is only an idea that we experience inside ourselves.”

THE FRAGMENTED WOMAN

In the 1930s Magritte painted pictures of fragmented bodies or body parts. By assigning the human body to the level of an object, he addressed the issue of a picture’s reality and the relationship between reality and visual representation. In his shaped canvases (toiles découpés), the pictorial world suddenly takes on a reality of its own as an object.

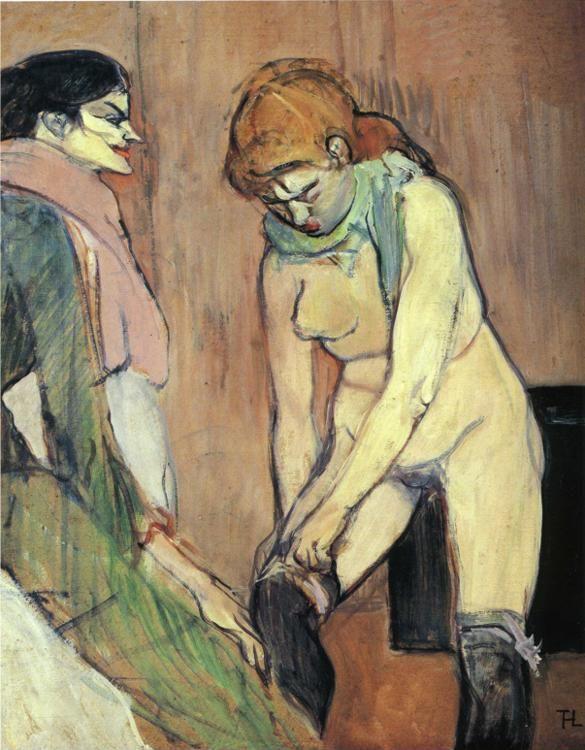

Surrealism pursued the cult of the object. The transfer of fragments of reality into a new setting stimulates our imagination and subconscious. To Magritte, the combination of things that seemingly cannot be brought together, subsequently forming a new and surprising union, was a manifestation of reality as an absolute entity. It was above all the woman as a symbol of the origins of the world that sparked the Surrealists’ fantasies of transformation and distortion.

An obsessive fascination for the female body runs through Magritte’s entire œuvre. In contrast to the male figure, which he always depicted fully dressed and well adjusted to society’s conventions, he mostly rendered women in the nude: as puppet-like figures or fragmented. The figure becomes a substitute for the human individual. Variably exchangeable and combinable, it reflects the ambiguity of the manifestations of reality.

METAMORPHOSIS In paintings like The Red Model Magritte experiments with metamorphosis, the transformation of one object into another: “I have found a new potential inherent in things – their ability to gradually become something else. This seems to me to be something quite different from a composite object, since there is no break between the two substances.” With this method of gradual transformation, Magritte sought to find an answer to the question of what gives shape and meaning to our existence.

APPLIED ART

LLike many students and young artists, Magritte earned his living with commercial commissions. In 1921 he designed ornamental patterns for a wallpaper manufacturer: “I bear the factory just as badly as the barracks,” he wrote later on. “After one year as an employee I gave up and maintained myself by doing idiotic jobs: commercial posters and drawings.” He designed advertisements for a fashion house and covers for music scores that were marketed by his brother, a music publisher. He also conceived stage settings for the theatre.

In 1931, after his return from Paris, Magritte and his brother founded the Studio Dongo, a two-man workshop producing window decorations, advertising signs, photomontages, and advertising copy. The artist worked in advertising for more than fifty years (1918–1966). Like his paintings, his designs were based on a reorganization of “real” objects and contained, starting as early as 1926, such motifs as curtain, fan, baluster, and bell.

SUNLIT SURREALISM

“I leave to others the business of causing anxiety and terror and mixing everything up.” René Magritte

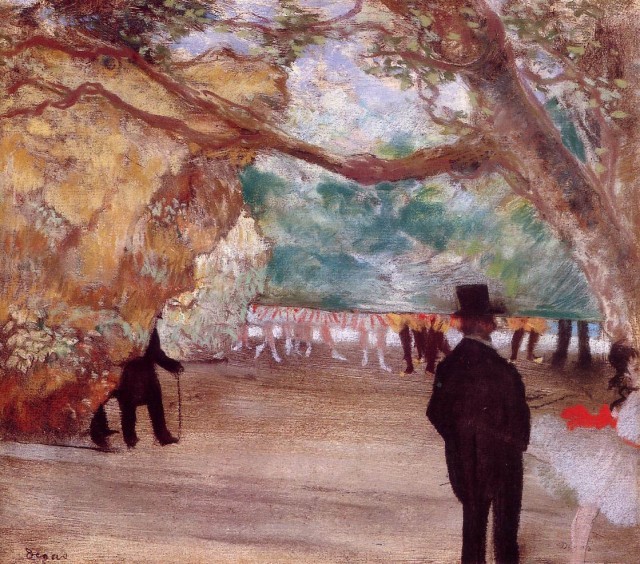

During World War II, Magritte’s style changed radically. In 1943 he suddenly took to painting Impressionist pictures in bright colours. He chose appealing subjects, such as bathers, female nudes, and flower still lifes in the manner of Rubens and Renoir. In contrast to his earlier visual language, which had by no means been devoid of violence, he was now celebrating, if ironically, “the beautiful side of life” and “a feast for the eyes and the mind”. Magritte devised his “Sun Period” as a subversive response to the tendency of Parisian Surrealism towards an obscure, “magical-esoteric ideology”. In his hedonistically tinged treatise Sunlit Surrealism (1946), he pleads for the “predominance of pleasure”. This conscious separation from the Parisian Surrealists marked a deep crisis between Breton and Magritte that led to fierce polemics. In the Paris exhibition Le Surréalisme en 1947, Breton condemned Magritte’s concept of a new Surrealism, relegating his works to a room entitled “former Surrealists”. Magritte was ultimately excluded from the circle of Surrealists.

PÉRIODE VACHE – THE SUBVERSIVE AESTHETICS OF THE ORDINARY

“The ‘vache’ period unites works of a sparkling liberty: in them, boorishness mingles with wit, indignation with amazement, violence with tenderness, and wisdom with hoax.” Louis Scutenaire

In 1948 Magritte received his first and long-awaited solo exhibition in Paris, the hub of the art world and Surrealism. Disappointed about the late recognition and estranged from Breton, he used the show as a revenge directed at the elitist intellectuals of the Paris art scene. Within the short period of five weeks, he had painted thirty-nine pictures and once again created a shock with the new and radical style of tastelessness that marked his Vache Period: furiously painted works, inspired by popular culture, comics, and caricature, and in crass opposition to the rest of his carefully conceived and thoroughly reflected pictorial inventions. The coarse painting style and the gaudy colours that were an offence to good taste were in line with the provocative, obscene, kitschy, and grotesque subject matter. By challenging his own identity as an artist, the civilized rules of the art business, and the validity of aesthetic standards, he responded to the reactionary attitude of Breton’s rigid Surrealist movement. The Parisian audience, many friends, and particularly Breton’s group regarded this experiment as an insult. They did not understand that Magritte had actually staged a truly Surrealist display of blasphemy.

THE FIDELITY OF IMAGES

NNot only did Magritte paint enigmatic scenarios, but he also used them as a basis for his photographs and short films. He started taking pictures in the 1920s. While many photographs are snapshots and record absurd Surrealist activities or simply document everyday life, others provide glimpses of his work as an artist. Although Magritte dealt with photography throughout his life, he was critical of the medium. In his opinion, the deceptive objectivity with which the photographed objects presented themselves went hand in hand with a lack of imagination. For him, photography was primarily a method of experimentation. His amateur pictures give the impression of “staged snapshots” containing typical features of his work as a painter: odd activities, the weird encounter of disparate objects, and the play with veiling and revelation.

MAGRITTE'S HOME MOVIES Between 1956 and 1960, Magritte shot some forty short films in which he appeared together with his wife and friends. He had been a film enthusiast even as a child and particularly loved slapstick comedies by Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy or Charlie Chaplin. In their sudden interruption of events, their bizarre sense of humour, their taste for the unexpected, and their staging of absurdities, his amateur films follow in this cinematographic genre.

THE DOMINION OF LIGHT

“This evocation of night and day seems to me to have the power to surprise and delight us. I call this power poetry.” René Magritte

Leaving the episodes of experiment behind him, Magritte returned to his well-tested methods and earlier manner of painting. From 1949 to the late 1960s, he painted the series L’Empire des lumières (The Dominion of Light). While the pictures may vary in terms of format and size, the subject is always the same: a blue cloudy sky in daylight appears above a row of houses rendered in nocturnal darkness, only lit by a street lantern. Through this reconciliation of opposites, a system of contextual paradox, day and night are inexplicably brought together.

THE VOICE OF MYSTERY “The Surreal is but reality that has not been disconnected from its mystery.” René Magritte

“Mystery” is at the core of Magritte’s art, the focus of all his pictorial inventions. Unlike the Surrealists in Paris, he did not equate the unknown with the unconscious: “The mystery is not one of the possibilities of the real. The mystery is that which is absolutely necessary for there to be a real.”

After the war, Magritte no longer felt like solving puzzles, but painted objects encouraging us to experience the world anew. In the 1950s his paintings became increasingly monumental: they deal with the reversal of scale and feature oversized objects within narrow rooms or petrified scenarios. Magritte invalidates spatial proportions and the laws of gravity by enlarging stones and apples to gigantic dimensions or causing them to float in space.

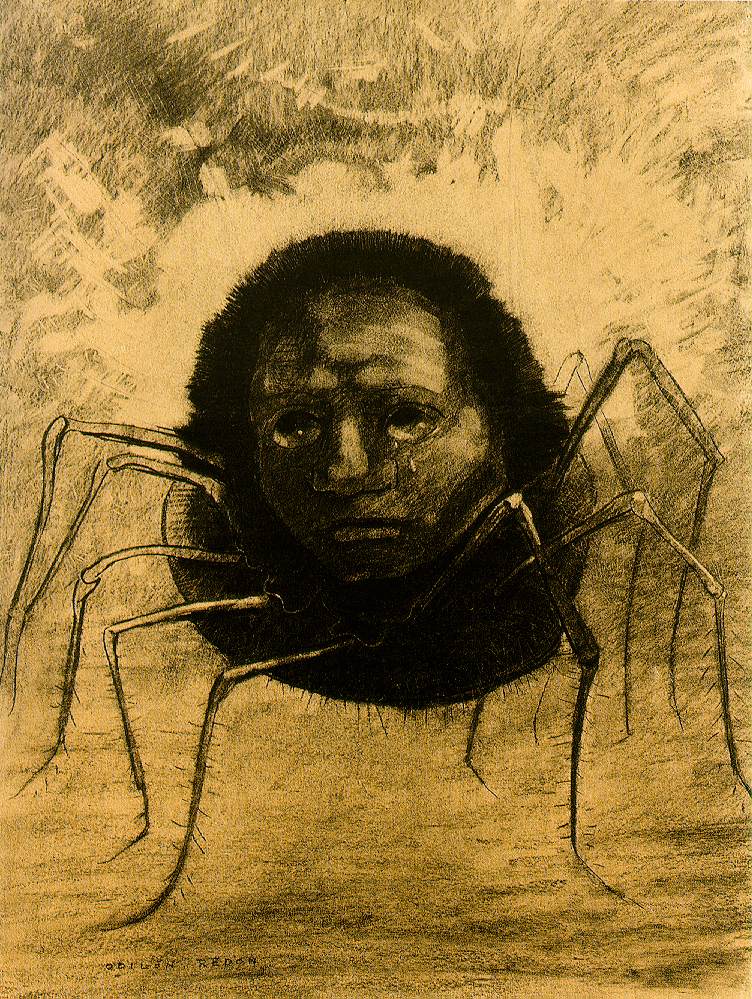

In his writings and lectures, Magritte pleads for the liberty of thought and unrestrained thinking, independent of habit and experience. He calls for an unbiased visual perception that is freed from reflection and interpretation and is unintentionally directed exclusively at what is being perceived. His pictures of petrified living creatures, fabulous beasts, still lifes, and landscapes play with the idea of metamorphosis. Here the transformation has already been concluded. It is the visual

expression of the “standstill of thought” Magritte was striving for: “One cannot speak about mystery, one must be seized by it.”

VISIBLE POETRY

“The indifference of stones is undoubtedly the same as the indifference of nothingness.” René Magritte

In the 1950s and 1960s, Magritte conceived compositions in which stones hover weightlessly in space. The stone’s heaviness cannot be logically associated with its lightness in the picture. Magritte took the liberty of determining the phenomena of the world at his own discretion and assigning a logic to it that contradicts the laws of nature and our habitual perception. With this deviation from visible reality, he advances into the realm of the surreal.

Magritte distinguishes between the dream as sous-réalité and his painting, which passes into the surreal through poetry. His pictures are “self-willed dreams” that have nothing vague about them.

THE BOURGEOIS AS CAMOUFLAGE

“I, for my part, have come to grips with the fact that I will lead a rather unglamorous existence to the very end.” René Magritte

From the very outset, Magritte developed a tendency towards dissolution and deconstruction, towards abstraction and anonymity. A distinct revival of this can be seen in his figural paintings of the 1960s. The mysterious man in a black suit and bowler hat relates to a protagonist of his early works. Magritte understood the late bowler-hat portraits as “anonymous self-portraits”.

Magritte lived in a discrepancy between his anarchist self and his inconspicuous look. The desire to attract attention, which the artist achieved by disrupting the familiar order of things, was contradicted by his appearance in public as an ordinary citizen. Donning a suit and a bowler hat, he consciously disguised himself as “one among many”. Together with his frequently emphasized indifference to his origins and past and his rejection of everything considered to shape one’s character, this attitude is reflected in his art through objects deprived of their meaning and the lack of emotion characterizing his painting style.

HEADLESS FACES In his so-called “failed portraits” (portraits manqués), Magritte further elaborated on the concept of anonymity by displaying figures viewed from behind, or by covering their faces and heads or replacing them by banal objects: his protagonists are void of any individuality and of an unapproachable aloofness, without any relation to their surroundings and caught in mysterious pictorial worlds like spectres. Such works subsist on a dual sense oscillating between the forlornness of existence in reality and the ego’s dissolution.

RENÉ MAGRITTE 1898–1967

1898–1924: Childhood, Youth, and Artistic Beginnings

René Magritte is born on 21 November 1898 in Lessines, Belgium. His mother is a milliner, his father a merchant tailor and travelling businessman. After his mother’s suicide in 1912 – one night she jumps off a bridge into a river – Magritte and his two younger brothers are entrusted to the care of governesses. The memory of the sight of his dead mother, a cloth covering her face, recurs in Magritte’s œuvre in the form of shrouded heads.

At seventeen Magritte enters the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He earns his living as a pattern designer in a wallpaper factory and later works as a commercial artist; it is only from the 1950s on that he can make a living with his art.

In 1922, Magritte marries Georgette Berger (1901–1986), who sells art supplies and pictures at an art dealer’s shop in Brussels. The encounter with Giorgio de Chirico’s work comes as a revelation to Magritte and paves his way to Surrealism.

1924–1930: Magritte and Surrealism in Paris and Brussels

In 1924, André Breton publishes the First Manifesto of Surrealism, in which the free flow of consciousness stimulated by the method of automatic writing (écriture automatique) is declared the basis of all Surrealist art. In the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1929), Breton assigns a prominent place to the paradoxes of dreams, the enigmatic realism of unfathomable pictorial worlds, and narration. This programme pushes the art of Magritte, Dalí, and Max Ernst to the fore.

In 1927, Magritte has his first solo exhibition. Within a short period of time, he paints 280 pictures – one quarter of his entire œuvre – including such major and famous works as The Menaced Assassin and The Secret Player. That same year Magritte and his wife move to Paris. He meets the French Surrealists grouped around André Breton, Jean Arp, Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, and Joan Míro.

He paints his first text-image pictures. His seminal text Words and Images is published in the Parisian Surrealists’ magazine La Révolution surréaliste. In 1930, following a quarrel with Breton, who dislikes the cross necklace Georgette wears, Magritte and his wife return to Brussels. The artist distances himself from Breton’s group.

1930–1954: First Success, Escape, and a New Beginning Because of the German invasion of Belgium, Magritte seeks refuge in Carcassonne in the South of France for a period of three months. For lack of canvas, he starts painting on bottles.

After the end of the war, the Belgian Surrealists take to shocking the public with blasphemous and antipatriotic publications. Magritte illustrates books dealing with emotional, sexual, and moral abysses. At the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris in 1947, Breton condemns Magritte’s new anti- aesthetic approach, which combines slapstick, pornography, religious blasphemy, kitsch, comics, and deliberately bad painting. For this group of works, which essentially amounts to a Surrealist mission, the artist coins the name “Vache Period”: it is the phase of vulgarity in his œuvre. Magritte is ultimately excluded from the Surrealist circle.

1954–1967: The Breakthrough to Success

Magritte has his first one-man show in New York already in 1936. Yet the artist’s actual triumph in the United States only begins with his exhibitions held there from 1954 on. In the years to come, numerous retrospectives take place in the USA.

Magritte shoots experimental short films and Surrealist home movies.

In 1965, Magritte’s health deteriorates. In the last years of his life, the artist engages in a lively exchange of ideas with the French philosopher Michel Foucault. These discussions inspire Foucault to write his essay Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

Magritte dies of pancreatic cancer on 15 August 1967, at the age of sixty-eight.

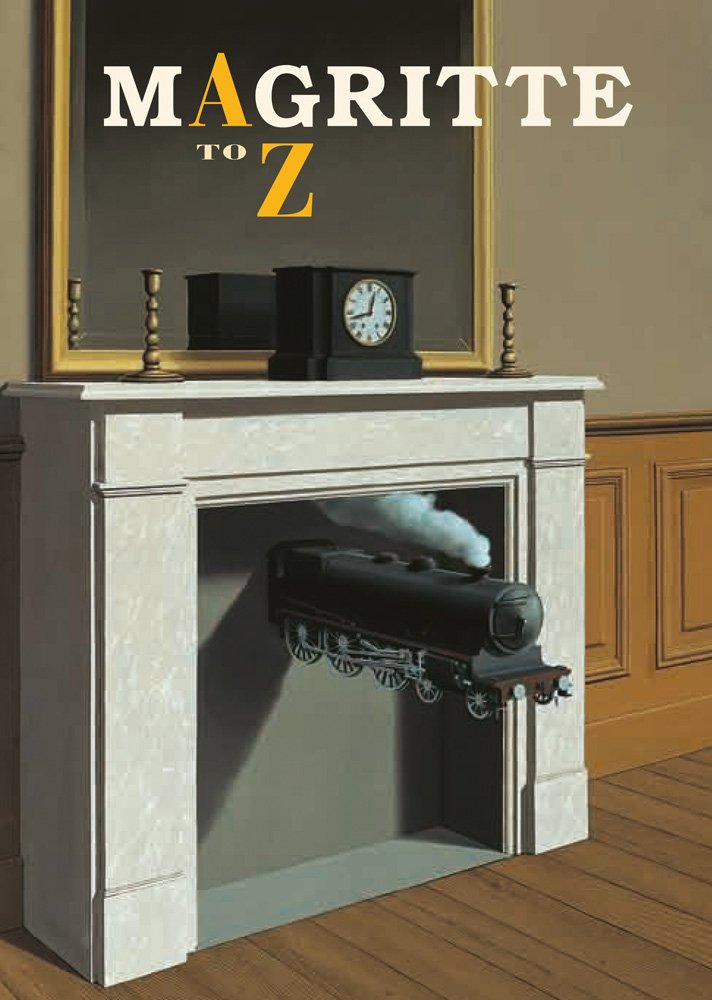

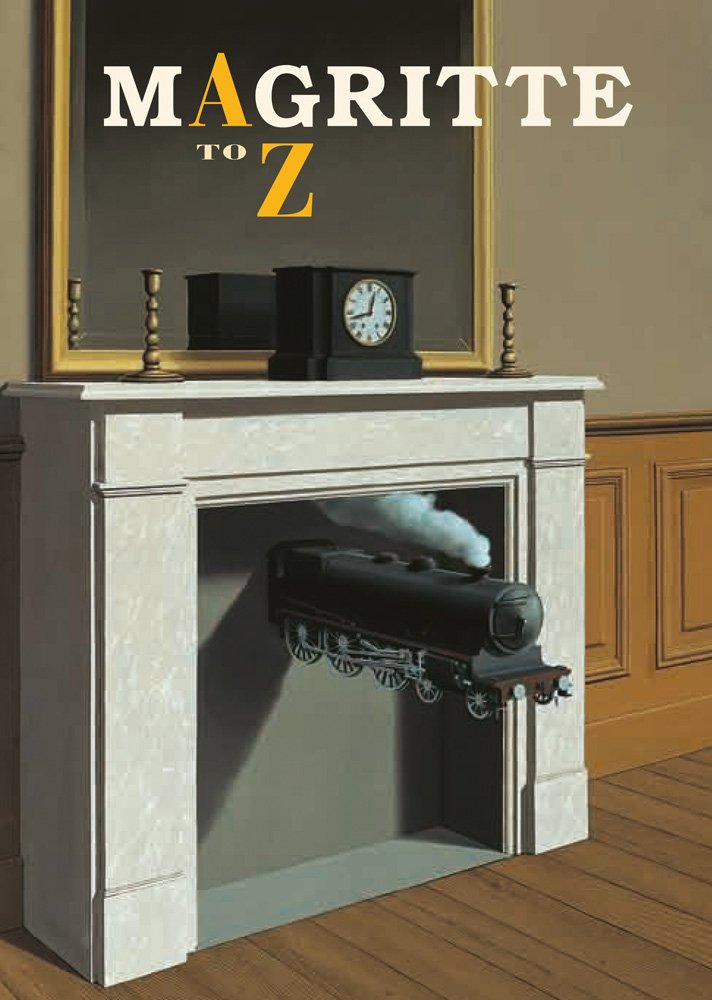

This book

This book explores the full scope of Magritte’s work through the format of an A to Z, fully illustrated in color, with entries written by a range of international scholars. The entries under the letter A alone—Absence, Abstraction, Appropriation, Anonymity, Artifice, Automatism, and Automatic Writing—show how this approach reveals and explores the themes and motivations in this most enigmatic artist’s work.

.jpg)