Monday, December 31, 2012

Work by Great Venetian Artist Titian at the National Gallery of Canada

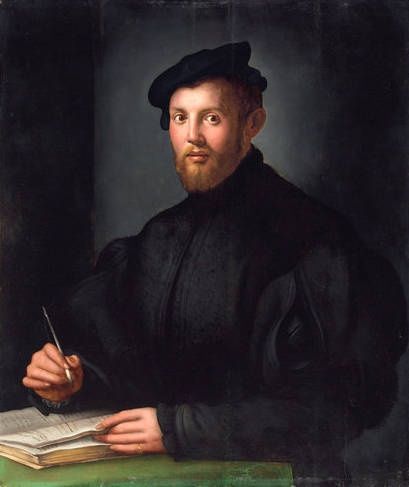

Tiziano Vecellio (called Titian), Daniele Barbaro, 1545. Oil on canvas, 85.8 x 71.5 cm. Purchased 1928. National Gallery of Canada. Photo © NGC

A portrait, its authenticity long questioned and in such poor condition it could not be shown, finally reclaims its rightful place in art history and on the walls of the National Gallery of Canada. Thanks to its recent restoration, Daniele Barbaro (1545), the only painting by the Venetian painter Titian in Canada, can now be exhibited to the public.

A Once Famous Painting

Daniele Barbaro (1514-1570) was a well-known scholar and humanist. The Gallery’s portrait was painted for the historian and collector Paolo Giovio, Bishop of Como in Italy. Over his life-time, he assembled a huge and celebrated collection of portraits. It was an honour to have your likeness included, and when Giovio wrote to Daniele Barbaro asking for his, Barbaro agreed and commissioned Titian, the greatest painter in Venice. The result was well-documented in letters between Giovio and the notorious Pietro Aretino, a famous writer and “publicist” for Titian. Both men praised the work, and their letters guaranteed its fame. And so when the painting was rediscovered in the 1920s, the Gallery was happy to buy it.

Yet the story was not so simple. Another version of the portrait was already known, held in the Prado Museum, Madrid. The rediscovery of Giovio’s painting challenged its position. Scholars debated the relationship of the two works: sitters often commissioned multiple versions of their portraits, yet which was the original, which the copy? Were both by Titian? Opinion swung back and forth until 1991, when the two paintings were compared side-by-side at a specially arranged meeting. The conclusion seemed inescapable: the NGC version was a copy made in Titian’s workshop. Barbaro had sent a copy to Giovio, and kept the prime version for himself.

A Titian Rediscovered

The painting was then kept in the Gallery’s vaults, largely forgotten until 2003. That year, a Canadian art lover wrote to the Gallery, asking why such a famous work was in storage. The answer was simple: it was a copy and, as well, in poor condition. There was no reason to exhibit it. Yet the letter sparked a chain of events that led to the painting’s restoration and rediscovery.

The painting had been badly damaged over the centuries, and past restorations had not solved all the problems. In fact, it was very difficult to judge its quality. Could that have effected scholars’ judgements? Stephen Gritt, Director of Conservation and Technical Research at the Gallery thought it merited a second look. This began a long process, carried off and on over several years, to examine, clean and restore the painting. The results were a surprise.

Examination revealed a damaged work, but one painted with great sensitivity and skill. It could not be a copy. When the chance came to compare the x-radiographs of both paintings, Gritt went to Madrid. “I spent an afternoon in front of a light-box with the Prado’s technical documentalist. By painstakingly comparing subtle features of execution as revealed on the X-ray, we were able to demonstrate that while the paintings were painted more or less at the same time, the Ottawa canvas was the one with all the thinking in it, the one that leads the way,” he explains.

With the X-ray images side by side, Gritt saw that the Ottawa painting contained subtle changes indicating that Titian had altered the colour of the clothing and adjusted the collar height, and most significantly, had wrestled with the sitter’s prominent nose to get it just right. In the Prado painting, however, the final look of the painting was arrived at more directly, because these problems had already been addressed. In fact, the two works had been painted side by side – not uncommon at the time. The Gallery’s portrait was the one on which Titian worked out the placement of detail and colour, and was most likely finished with Barbaro present.

Titian

Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian (c.1488-1576) is among the greatest artists of the Renaissance. His work was celebrated by his contemporaries, and avidly collected by the Hapsburgs, rulers of much of Europe and the Americas. A portrait by Titian was a penetrating, subtle exploration of character – as well as the ultimate status symbol for its sitter. The artist was also famed for the sophistication of his mythological and religious subjects, which were seminal to development of painting in the next century. Titian created an inimitable, highly personal style that forever changed the art of painting.

Christie’s New York : Renaissance - Featuring Works by Bronzino, Fra Bartolommeo, Cranach & Botticelli

On 30 January, Christie’s New York will present Renaissance, a sale devoted to the artistic traditions that flourished in Europe from 1300 to 1600. A highlight of Old Masters Week in Rockefeller Plaza, the sale will celebrate the golden age that produced some of the most extraordinary innovations in poetry, music and literature, painting, sculpture, and architecture. Renaissance will feature a select group of paintings, works on paper, tapestries, prints and maiolica from some of the greatest masters of the era who were active throughout Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and France. Masterpieces by Sandro Botticelli, Fra Bartolommeo, Bronzino, and Lucas Cranach the Younger are among the highlights of the sale, which is comprised of 51 lots and is expected to realize in excess of $40 million.

Leading the sale is premier Florentine portraitist Agnolo Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Book, one of the most important Renaissance portraits remaining in private hands ( estimate: $12,000,000-18,000,000). Recently rediscovered, the Portrait of a Young Man with a Book is among Bronzino’s earliest known portraits, datable to the time he was most closely associated with his teacher, Jacopo Pontormo, whose stylistic influence is clearly visible here. While the sitter’s identity cannot be confirmed, his social status and profession are alluded to. Elegantly attired and shown writing in a manuscript with a quill pen, he is clearly a cultivated man of letters. The seeming spontaneity of the sitter’s pose and direct gaze toward the viewer suggest that he may have been a close friend of the artist.

Fra Bartolommeo’s beautifully preserved The Madonna and Child, still set in its original frame, is an important recent addition to the artist’s oeuvre (estimate: $10,000,000-15,000,000). Likely executed in the mid-1490s, early in Fra Bartolommeo’s career, this tondo-shaped panel depicts a tender moment as the Christ child eagerly grasps his mother’s veil, pulling himself up to receive a kiss. For more information on this lot, please click here.

Sandro Botticelli’s Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist is also among the highlights of the sale (estimate: $5,000,000-7,000,000). Intended for private devotional use, the work depicts a popular subject in Florence, as Saint John the Baptist was the patron saint of the city; his presence was likely intended to signal that the patron was a Florentine patriot. The tender sentiment between mother and child is here combined with an allusion to the Resurrection in the tomb-like structure carved with a classical relief just behind the figures. The diaphanous veil which falls over the Madonna’s head and shoulders signifies her purity, as this was the traditional head covering of unmarried Florentine women. The painting comes to market with a highly distinguished provenance, having been acquired in the early 1930’s from Lord Duveen by John D. Rockefeller. It remained in the Rockefeller family for some 50 years, and has more recently passed into a private New York collection, though it is still widely referred to as “the Rockefeller Madonna.”

Raphael’s remarkable drawing of Saint Benedict receiving Maurus and Placidus represents the moment when Saint Benedict receives his first disciples, a key episode the history of the Benedictine Order (estimate: $1,000,000-1,500,000). The drawing can be dated to circa 1503, early in the artist’s career, when he was collaborating with Pinturicchio on

the fresco cycle in Siena’s Piccolomini Library, for which Pinturicchio had been commissioned to paint frescoes depicting events from the life of Pope Pius II. It is likely that in their collaboration, Raphael was only involved in the earlier stages of the commission, executing preliminary compositional drawings rather than assisting with the execution of the frescoes themselves. This lot may be one such preliminary drawing, as it bears remarkable similarity in style, technique, and composition to a drawing housed in the J. Pierpont Morgan Library in New York that has been confirmed as related to the Piccolomini Library.

The drawing may also be linked to the Benedictine monastic community at Monteoliveto Maggiore, as the same central group of the elderly bearded man and the kneeling young boys was used by Sodoma (1477-1549) in his fresco of Saint Benedict receiving Maurus and Placidus, executed for the monastery in about 1505.

Scipione Pulzone, Called Il Gaetano (Gaeta 1544-1598 Rome), Portrait of Jacopo Boncompagni, three-quarter length, in armor. signed, dated and inscribed ‘Scipio Gaietano faciebat./1574’ oil on canvas 47 5/8 x 38 7/8 in. (120.9 x 98.7 cm.). Estimate $1,500,000-2,500,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

A Portrait of Jacopo Boncompagni, executed in 1574 by Scipione Pulzone, is a stunning example of the artist’s famed portraiture and was previously exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (pictured right; estimate: $1,500,000-2,500,000). The letter held in the sitter’s hand identifies him as Jacopo Boncompagni, the natural son of Pope Gregory XIII and commander of the Papal army. Boncompagni’s role is underscored by the inclusion of a victorious St. Michael on his breastplate and the armorial decoration all’antica, which served the purpose of associating its wearer with ancient Roman military heroes. For more information on this lot, please click here.

Fresh to the market, The Temptation of Saint Anthony by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch has a distinguished provenance, having been owned by the French writer Victor Hugo, who acquired the work in Brussels in the 1860s (estimate: $400,000-600,000). Among the earliest of the Christian monks, Saint Anthony the Great was the first to abandon society for a solitary existence in the wilderness. Depicted here is the famous scene in which Saint Anthony is tempted by the Devil, who unsuccessfully appears in myriad forms to coax Anthony from the path of Christian righteousness.

A favorite subject of the great Netherlandish artist Hieronymous Bosch, the saint's story was ideally suited to his personal belief that a blissful eternity in Heaven would await those who led an honorable life. In order to accentuate the consequences of a sinful life, he created a richly inventive repertoire of fantastical motifs, which are included in the present example. Despite the horrors that surround him, however, Saint Anthony remains stoic as he walks through the landscape.

Beautifully preserved, richly colored and intimately sized, Saint Paul in his Study ranks amongst the finest religious works executed by Lucas Cranach the Younger (estimate: $400,000-600,000). Saint Paul, identified by the sword of his martyrdom, is seated at a stone pulpit, writing his Epistles in a sparsely decorated room that opens to a fanciful rocky landscape. The artist’s characteristically elegant and graphic style is evinced in the confident outline of the figure and the delicate serpentine strokes that make up for the saint’s curly hair and beard. This is the only known depiction of this subject by the artist, which is truly exceptional for Lucas Cranach the Younger, who commonly produced multiple variants of his religious and historical themes.

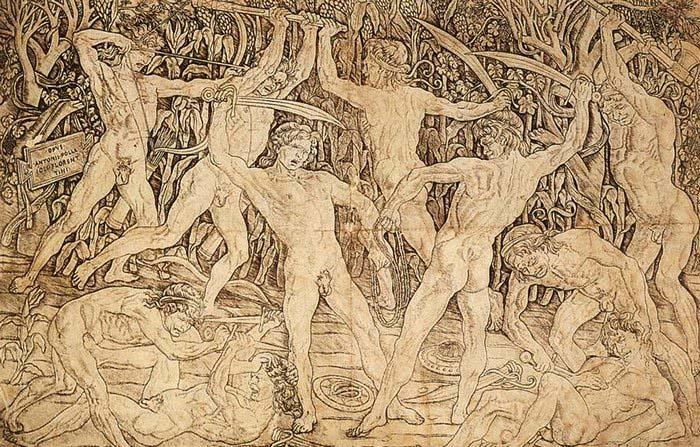

Antonio Pollaiuolo’s only known engraving, The Battle of the Nudes, is a milestone in Quattrocentro printmaking and one of the most influential prints produced in Renaissance Florence (estimate: $700,000-900,000). While depicting ten nude males in a fiercely violent battle, the lack of a clear narrative has led scholars to believe that its creation was an artistic exercise in anatomical composition, portraying the human form in various poses, also to be used for instructive purposes. The significance of the work is underscored by the fact that it is one of the few prints to be mentioned by Vasari, who lauded Pollaiuolo for his technical abilities in portraying the male form. Pollaiuolo was so pleased with the result, and confident of its success, that he signed his name in a plaque at the right of the subject – the first engraving to bear an artist’s full signature.

Inventing Abstraction: 1910–1925

Museum of Modern Art (NYC) December 23, 2012–April 15, 2013

Inventing Abstraction: 1910–1925 explores the advent of abstraction as both a historical idea and an emergent artistic practice.

František Kupka. Localization of Graphic Motifs II. 1912–13. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 x 76 3/8" (200 x 194 cm), frame: 78 3/4 x 76 3/8" (200 x 194 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund and Gift of Jan and Meda Mladek. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

In 1912, in several European cities, a handful of artists—Vasily Kandinsky, Frantisek Kupka, Francis Picabia, and Robert Delaunay—presented the first abstract pictures to the public. Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925 celebrates the centennial of this bold new type of artwork, tracing the development of abstraction as it moved through a network of modern artists, from Marsden Hartley and Marcel Duchamp to Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, sweeping across nations and across media. The exhibition brings together many of the most influential works in abstraction’s early history and covers a wide range of artistic production, including paintings, drawings, books, sculptures, films, photographs, sound poems, atonal music, and non-narrative dance, to draw a cross-media portrait of these watershed years.

Commemorating the centennial of the moment at which a series of artists invented abstraction, the exhibition brings together over 350 works in a broad range of mediums—including paintings, drawings, prints, books, sculptures, films, photographs, recordings, and dance pieces—to offer a sweeping survey of a radical moment when the rules of art making were fundamentally transformed. Half of the works in the exhibition, many of which have rarely been seen in the United States, come from major international public and private collectors. The exhibition is organized by Leah Dickerman, Curator, with Masha Chlenova, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture.

A key premise of the exhibition is abstraction’s role as a cross-media practice from the start. This notion is illustrated through an exploration of the productive relationships between artists, composers, dancers, and poets in establishing a new modern language for the arts. Inventing Abstraction: 1910–1925 brings together works from a wide range of artistic mediums to draw a rich portrait of the watershed moment in which traditional art was wholly reinvented.

Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925

Available exclusively at MoMA, this publication accompanies the exhibition Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925 (December 23, 2012–April 15, 2013).

To download a sample PDF of Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925 click here.

Saturday, December 22, 2012

The Age of Picasso and Matisse: Modern Masters from The Art Institute of Chicago

Some of the most celebrated works of modern art are coming to the Kimbell Art Museum in the fall of 2013. The Art Institute of Chicago holds one of the greatest collections of modern European art in the world. In the largest loan of its kind from the Art Institute, nearly 100 works from this collection will be traveling to the Kimbell Art Museum. The only venue for the exhibition, the Kimbell will present The Age of Picasso and Matisse: Modern Masters from the Art Institute of Chicago from October 6, 2013, through February 16, 2014.

“The Kimbell is proud to showcase Chicago’s treasures,” said Eric M. Lee, director of the Kimbell Art Museum. “Some of the great icons of modern art will visit Texas for the first time—paintings like

Pablo Picasso’s Old Guitarist

and Henri Matisse’s Bathers by a River.

Henri Matisse, Bathers by a River, March 1909–10, May–November 1913, and early spring 1916–October (?) 1917, oil on canvas, 102 1/2 x 154 3/16 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

© 2012 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

With nearly 100 paintings and sculptures on view, this will be the most important exhibition ever drawn entirely from the renowned modern holdings of the Art Institute.”

Among the works in the exhibition—which spans the first five decades of the 20th century—are 10 by Picasso and 10 by Matisse, the friends and rivals whose paintings revolutionized Parisian art at the turn of the century. Bold and brightly colored canvases by Matisse and his Fauve colleagues Maurice de Vlaminck and Georges Braque open the exhibition, followed by the complicated and subtly toned Cubist images of Picasso, Braque and Juan Gris.

The major movements of European modernism are represented by superb examples. Vibrant paintings by German and Russian artists—notably Max Beckmann, Vasily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall—will contrast with the reductive purity of abstractions by the sculptor Constantin Brâncusi and the painters Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian. Chicago’s famous collection of Surrealist painting and sculpture will be shown in strength, including pieces by Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Max Ernst, Paul Delvaux, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Paul Klee, Alberto Giacometti and Picasso. A concluding gallery will feature works from the years around World War II by Picasso, Matisse, Chagall, Balthus and Fernand Léger.

Kimbell Art Museum

The Kimbell Art Museum, owned and operated by the Kimbell Art Foundation, is internationally renowned for both its collections and for its architecture. The Kimbell’s collections range in period from antiquity to the 20th century and include European masterpieces by artists such as Fra Angelico, Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Poussin, Velázquez, Monet, Picasso and Matisse; important collections of Egyptian and classical antiquities; and Asian, Mesoamerican and African art.

The Museum’s building, designed by the American architect Louis I. Kahn, is widely regarded as one of the outstanding architectural achievements of the modern era. A second building, designed by world-renowned Italian architect Renzo Piano, is scheduled to open in 2013 and will provide space for special exhibitions, allowing the Kahn building to showcase the permanent collection.

El Greco THE ENTOMBMENT OF CHRIST

DOMENIKOS THEOTOKOPOULOS, CALLED EL GRECO

CANDIA (HERAKLEION), CRETE CIRCA 1541 - 1614 TOLEDO

THE ENTOMBMENT OF CHRIST

Estimate: 1,000,000 - 1,500,000 USD

Sotheby's Auction Property from the Estate of Giancarlo Baroni

New York | 29 - 30 January 2013 | N08857

This touching early panel by El Greco has until now remained largely unknown by the general public and unseen by art historians. It was in private hands until 1974, when it was sold as part of the Estate of Mme. Gegette Broglio and appeared in only a single public exhibition, in Venice, in 1981. Alvarez Lopez included it as an autograph work by El Greco in his 1993 catalogue raisonné, but in his later catalogue of 2007 he equivocated referring to it as possibly by El Greco or possibly a copy after him.1 This indecision was due to his not having seen the original painting and having to judge instead from poor reproductions or photographs. This was, in fact, the case for virtually all the scholars who had written about The Entombment apart from Mayer and Pallucchini. Happily the current leading authority on the works of El Greco has now had the opportunity to study the panel first hand and has confirmed that it is an autograph, early work.

The present work is one of four recorded versions of this composition: the first is a panel formerly housed at the Palacio Real, Madrid, but never part of that collection. It may have been the property of Manuel Asúa, an employee at the Palacio, and is sometimes thought to have been from the Salamanca collection, but the full history of the painting has never been properly established.2 It disappeared in 1936, at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, and its present location is not known. The only real record of it is a 1928 black and white photograph, the negative of which is the basis for all reproductions. Although some authors believe that the present work is identical with the Madrid picture the visible differences in the compositional details make that very unlikely, even allowing for possible restoration or cleaning. The panel here was first published in 1949, but it had been recognized earlier by August L. Mayer as an autograph work by El Greco.3 A third panel was published by Martin Soria in 1954 as being in the collection of the Conde Viuda de Ibarra, Seville. It is in oil on panel and has been dated by Álvarez Lopera to circa 1571-72.4 It is smaller than the present work (28.1 by 19 cm) and is now in a private collection, London. A larger panel (45 by 27.4 cm) from the Anstruther collection was sold at Christie's, London, March 19, 1965, lot 44. According to the note in the catalogue, it was framed to give it an arched top, but the corners had been filled in and painted over. Included by Steinberg in his article in 1974 without a comment about the attribution, it is scarcely mentioned in the recent literature.5

El Greco left his native Crete sometime after 1566 and by 1568 was documented in Venice where he may have worked in Titian’s studio. In late 1570 he was in Rome, having passed through Verona, Parma and Florence along the way. The present work probably dates to the mid-1570s, a remarkably fertile period for El Greco, during which he was relinquishing the hieratic style derived from icon painting and turning to contemporary Italian art for inspiration. His setting for The Entombment is a place of total desolation. A tall rounded hill top with some vegetation sprouting from it rises in the middle ground. Its sharp and stony presence is reminiscent of the larger but equally barren hills on the reverse of the Modena triptych, one of his most important early works. The background is cut off by a range of cold distant peaks. In the sky above the clouds are wild and disturbed, reflecting the feelings of those present, while the light from the setting sun brings no comfort to these grim surroundings. The landscape is devoid of any human presence apart from the figures at the burial, who are gathered in distinct groups. In the foreground is the Magdelen, in her bright orange robe, kneeling by the sepulcher and supporting Christ’s limp arm. Three young men and an older, bearded figure who might be Nicodemus, lower Christ into his tomb. Behind them are smaller figures who observe the scene but are detached from the action. At the right is the Virgin, who tenderly caresses her son’s feet and legs, and a group of elegant female mourners.

Despite the brevity of El Greco's stay in Venice, we see its impact here and in his painting from the early 1570s onwards. In the present work it is evident in the artist’s use of color, particularly the Magdalen's brilliant robe, and in the general structure of the composition, which has the crowded activity of Titian's late paintings.

Comparing this to an earlier representation of the same subject in the National Gallery, Athens, datable to circa 1568-69, when El Greco was still in Venice, we can see the degree to which he has absorbed the influences of Italy.6 In the Athens picture the figure of Christ is shown with his face turned toward the viewer, rather than away and there are fewer figures attending him. The landscape is similarly barren in feel, but the coloring is much brighter and the handling of the paint broader. Here the brushwork is more refined and differentiated, and the artist glories in his depiction of the agitated drapery as well as the smooth skin of the elegant young men. In the Athens panel several of the figures are taken directly from etchings by Parmigianino, while in the present panel the references to Italian art are, for the most part, more fully integrated into the composition as a whole. The coloring is toned down, though the Venetian influence can be seen in the Magdalen’s brilliant robe, while general structure of the composition has the crowded activity of Titian's late paintings. Apparently as a tribute to his mentor, El Greco has also included a portrait of Titian in The Entombment: he is part of the group of observers, the second figure from the left with the black cap and white beard. The elegant elongated bodies and necks of both the men and women surrounding the tomb, owe a great deal to Parmigiano, but in contrast to the Athens picture, El Greco has, for the most part, not borrowed directly from earlier artists. The great exception is the figure of Christ himself, which, as Leo Steinberg convincingly demonstrated, is based on

Michelangelo's Pietà in the Duomo in Florence .7 The pose is the same, the relation of the limbs and torso are those of Michelangelo’s sculpture, but El Greco rotates the figure 90 degrees counterclockwise to make it suitable in the context of a burial. While later in his Italian sojourn, El Greco famously criticized Michelangelo, asserting that he could repaint the Sistine Chapel in a better and more seemly fashion, his quotation of the Pietà here seems not so much a challenge to the older artist but more a way of enhancing the emotional content of the painting while at the same time demonstrating his knowledge of Italian art. The Pietà was already well-known and much copied by the 1570s, and by introducing it into The Entombment El Greco was able to draw on the powerful emotions that the sculptural group elicited. It is also a sophisticated compositional device, connecting the disparate groups of mourners.

In 1577 El Greco left Italy for Madrid, and then Toledo, where he remained until his death. The paintings from his Spanish period, with their turbulence and distortion are what we generally associate with the artist, but the seeds for those pictures are all present here in this small panel, where elegance and emotion are combined, though the latter prevails.

Notes

1. See Literature for his and the earlier opinions regarding the attribution.

2. See H. Wethey 1974, see Literature for a summary of the known information.

3. L. Steinberg, p. 474, note 1, see Literature.

4. Álvarez Lopera 2007, cat. no. 29, see Literature.

5. L. Steinberg, loc. cit. Álvarez Lopera 2007, p. 84, refers to it in his note on the present work and Puppi 1999, p. 104 incorrectly identifies it as having come from the Ibarra collection. See Literature.

6. Álvarez Lopera 2007, p. 79, cat. no. 28.

7. L. Steinberg, pp. 474-477.

Exhibited

Venice, Palazzo Ducale, Da Tiziano a El Greco Per la Storia del Manierismo, September - December 1981, reproduced p. 27, cat. no. 106

Literature

E. Gonda, "Se ha descubierto en Ginebra un Greco desconocido," in Falange, Las Palmas, 10 May 1949;

A. Winkler, "Hallazo de un Greco," in Insula, IV, August 15, 1949, no. 44;

J. Camón Aznar, Domenico Greco, vol. II, Madrid 1950, p. 1367, no. 201 (as being identical with the painting formerly stored at the Palacio Real de Madrid) [a revised edition published in 1974];

R. Pallucchini, La Giovinezza di Tintoretto, Milan, 1950, p. 59, fig. 58 (as being identical with the painting formerly stored at the Palacio Real);

G. Fiocco, "Del 'Greco' veneziano e di un suo ritratto di Ottavio Farnese," in Arte Veneta, vol. 5, 1951, pp. 117-118, fig. 130 (as being identical with the painting formerly stored at the Palacio Real);

R. Pallucchini, "New Light upon El Greco's Early Career," in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, XL, July - August 1952, pp. 46-56, reproduced pp. 49 and 50, figs. 1 and 3 (as painted in Venice in 1576);

M.S. Soria, "Greco's Italian Period," in Arte Veneta, VIII, 1954, p 221, no. 63 (as painted in Toledo);

R. Pallucchini, Il Greco, Milan 1956, pp. 50-51, no. VI, reproduced p.17 (as painted on his return to Spain);

J. A. Gaya Nuño, La pintura española fuera de España, Madrid 1958, p. 188, no. 1205 (as painted in 1576);

H. Soehner, "Greco in Spanien," part III: "Katalog der Gemälde Grecos, seines Ateliers and seiner Nachfolge in Spanischem Besitz," in Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, vol. IX/X, 1958-59, p. 176, under cat. 4 (as possibly identical with the painting formerly in the Asúa collection);

H.E. Wethey, El Greco and His School, Princeton, 1962, p. 183, no. X-80 (as Follower of El Greco, circa 1580-85) [another edition 1967]

L. Puppi, "Il Greco giovane e altri pittori madonner di maniera italiana a Venezia nella seconda meta del Cinquecento," in Prospective, 1963, p. 42, reproduced p. 44, fig. 10;

E. Arslan, "Cronistoria del Greco 'madonnero'," Commentari. Rivisti di critica e storia dell'arte, vol. XV, nos. 3-4, July-December 1964, p. 230, note 31 (as being identical with the painting formerly stored at the Palacio Real);

R. Pallucchini, "Il Greco e Venezia," in Venezia e l'Oriente fra Tardo Medioevo e Renascimento (Corso Internazionale della Fondazione Cini, no. V, Venice 1963), Florence 1966, p. 369;

T. Frati, L'Opera completa del Greco, Milan 1969, p. 94, no. 18a (but reproduces 18b);

L. Steinberg, "An El Greco 'Entombment' Eyed Awry," in The Burlington Magazine, vol. CXVI, August 1974, pp. 474-477 (as dating from his Roman period, 1576);

H. Wethey, "El Greco's Entombment," in The Burlington Magazine, vol. CXVI, December 1974, p. 760 (as possibly identical with the painting formerly stored at the Palacio Real);

R. Pallucchini, La Pittura Veneziana del Seicento, Milan 1981, vol. II, reproduced p. 495, fig. 142;

R. Pallucchini, in Da Tiziano a El Greco Per la Storia del Manierismo, Venice 1981, p. 270, cat. no. 106, reproduced p. 271;

L. Puppi, "Ancora sul soggiorno italiano del Greco, in El Greco of Crete, Heraklion 1995, p. 253;

L. Puppi, "El Greco in Italy and Italian Art,” in El Greco. Identity and Transformation, exhibition catalogue, Madrid 1999, p. 104, reproduced p.107, fig. 6 (as datable to 1573-76);

J. Álvarez Lopera, El Greco. La obra esencial, Madrid 1993, p. 278, no. 28 (as autograph);

J.Álvarez Lopera, El Greco, Estudio Y Catálogo, Vol. II, Part I: Catálogo de Obras Originales: Creta. Italia. Retablos y Grandes Encargos en España, Madrid 2007, pp. 81-84, cat. no. 30, reproduced fig. 45 (as El Greco [?]. Copia de un original perdido [?]).

Provenance

Possibly a private collector in Aix-en-Provence (according to a partly legible inscription on the reverse);

European private collection;

Private Collection, Geneva, by 1939;

From whom acquired by Carlo Broglio, Paris, by 1949;

From whom inherited by his wife, Gegette Broglio, Paris;

Her Estate sale, Paris, Palais Galliera, March 19, 1974, lot 30 (as Attributed to Domenicos Theotocopuli dit El Greco), where acquired by Giancarlo Baroni.

A Note on the Provenance:

The early history of this panel is unclear, and, as noted above, the painting has sometimes been confused with the picture formerly stored at the Palacio Real de Madrid. After studying the 1949 newspaper accounts of the discovery of The Entombment and the evidence of the picture itself, we believe that the provenance differs somewhat from that in previous publications.

An inscription in pen on the reverse of the panel suggests it was in a private collection in Aix-en-Provence, in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, but we have been unable to identify who that might be, though there appears to be a street address on the Boulevard Roy René.

The picture first came to the notice of art historians before World War II, when it was identified by a curator at the Pinokothek in Munich, possibly A. L. Mayer himself. At that point it was in a European private collection. According to the two newspaper articles of 1949 (see Literature), the picture was in storage in Geneva by 1939 and during the war. Piecing the information together we believe that by 1949 it came to Carlo Broglio, the art dealer, who was then living in Paris. The suggestion that it was once owned by Mario Broglio, the journalist, seems to have been due to a confusion of the two men by later writers. The picture is then firmly documented as being in the collection of Gegette Broglio, Carlo's widow and was included in the sale of her estate, where it was acquired by the present owner.

Friday, December 21, 2012

American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe, opening December 22 at the Whitney Museum of American Art

Eighteen early to mid-century American artists who forged distinctly modern styles are the subjects of American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe, opening December 22 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Drawing from the Whitney’s permanent collection, the year-long show features iconic as well as lesser known works by

Oscar Bluemner,

Charles Burchfield, Paul Cadmus,

Alexander Calder,

Joseph Cornell,

Ralston Crawford,

Stuart Davis,

Charles Demuth, My Egypt, 1927. Oil on fiberboard, 35 3/4 °— 30 in. (90.8 °— 76.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;

Charles Demuth,

Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Gaston Lachaise, Jacob Lawrence, John Marin,

Reginald Marsh,

Elie Nadelman, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Joseph Stella.

Joseph Stella (1877–1946), The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme, 1939. Oil on canvas, 70 × 42 in. (177.8 × 106.7 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase 42.15

Curator Barbara Haskell has organized the museum’s holdings of each of these artists’ work into small-scale retrospectives. Many of the works included will be on view for the first time in years; others, such as

Hopper’s A Woman in the Sun,

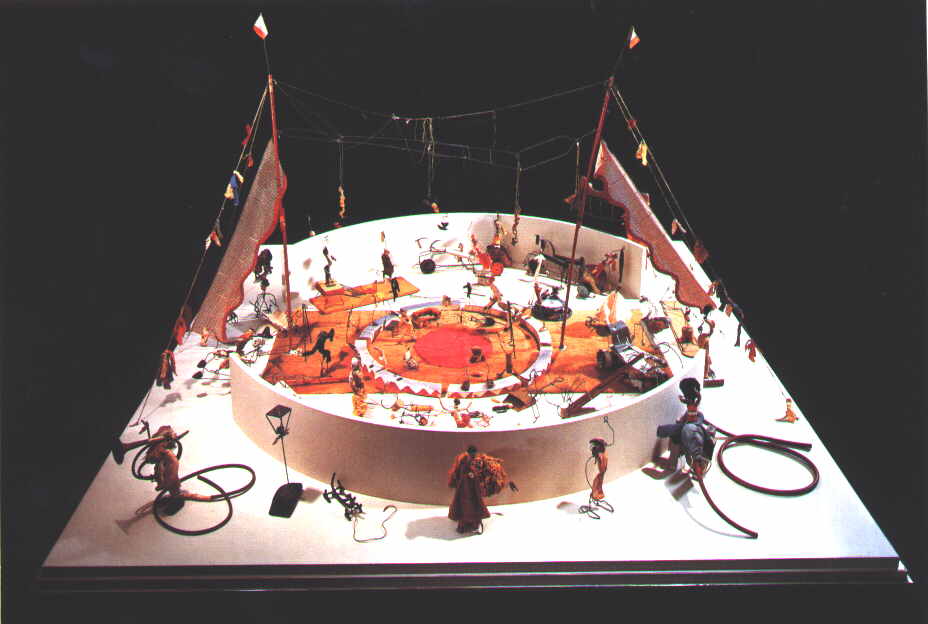

Calder’s Circus,

Jacob Lawrence’s War Series,

and Georgia O’Keeffe’s Summer Days,

are cornerstones of the Whitney’s collection.

The show will run for a year in the museum’s fifth-floor Leonard & Evelyn Lauder Galleries and both the Sondra Gilman Gallery and Howard & Jean Lipman Gallery on the fifth-floor mezzanine.

To showcase the breadth and depth of the Museum’s impressive modern art collection, a rotation will occur in May 2013 in order that other artists and works can be installed.

In the late nineteenth century artistic innovation was largely driven by European art. For aspiring young painters and sculptors in America, traveling to Europe and assimilating European styles was considered integral to becoming a modern artist. By the turn of the twentieth century, with America’s emergence as an international power, the nation’s artists began to reassess their earlier dependence on Europe in favor of creating independent styles, inspired by American subjects and forms of expression.

Two clear movements dominated art in the first half of the twentieth century: realism and modernism. “Despite their seemingly antithetical styles and subject matter, the two groups shared a determination to portray their intense connection to American subjects,” Haskell explains. “Together, they charted a new direction in American art and, in the process, redefined the relationship between art and modern life.”

By featuring realists, such as Hopper

Charles Burchfield, Noontide in Late May, 1917. Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper, 22 × 18 in. (55.9 × 45.7 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase 31.408.

and Burchfield,

alongside modernists, such as Bluemner and Stella, American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe represents the vitality and diversity of early twentieth-century American art. The Whitney has a long and proud history of supporting this work, as evidenced by the depth of its holdings of the eighteen artists in this exhibition.

Mary Cassatt and the Feminine Ideal in 19th-Century Paris

The Cleveland Museum of Art presents Mary Cassatt and the Feminine Ideal in 19th-Century Paris, an exhibition that explores Cassatt's images of women with those of her contemporaries such as Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Organized thematically and primarily drawn from the museum's permanent collection, the exhibition contains over 50 works on paper, depicting visions of femininity ranging from the bourgeois wife and mother to peasant women of the countryside to urban women at work in the ballet and the brothel. Mary Cassatt and the Feminine Ideal in 19th-Century Paris, is on view October 13, 2012–January 21, 2013 in the Cleveland Museum of Art's James and Hanna Bartlett Prints and Drawings Gallery.

The museum's strong holdings of works on paper by Mary Cassatt will be showcased in the exhibition. The collection includes more than a dozen prints spanning the range of Cassatt's activity as a printmaker from her first efforts in 1879 when she was working closely with Degas, to her famous suite of ten color prints of 1890–91 that depict the daily life of the modern, bourgeois woman of 19th-century Paris.

In addition to Cassatt's masterpiece in pastel,

After the Bath (c. 1901), a number of her drawings will also be on view, including studies for several prints in the exhibition.

The exhibition will explore Cassatt's experimental approach to printmaking, the medium in which she was ultimately most revolutionary.

While Cassatt celebrated bourgeois mothers and children, her male contemporaries turned their gaze to "public women," the actresses, dancers and prostitutes of the entertainment class of fin-de-siècle Paris. Mary Cassatt and the Feminine Ideal in 19th-Century Paris includes drawings in pastel and watercolor as well as etchings and lithographs by Degas, Édouard Manet and Toulouse-Lautrec that represent women of the era from a variety of perspectives. These artists address the darker side of the feminine ideal and examine the complex and often fraught idea of the "modern woman" in late 19th-century Paris. Peasant women working in the countryside are depicted in the work of Camille Pissarro and Auguste Renoir.

Numerous examples from the Cleveland Museum of Art's collection of pastels are highlighted in the exhibition—a rare opportunity for visitors to enjoy spectacularly colorful, light-sensitive works on paper. The exhibition also includes an 18th-century Japanese woodcut that exemplifies the influence of ukiyo-e prints on the work of Cassatt and her contemporaries. The McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX has agreed to lend one of Cassatt's color prints for which the Cleveland Museum of Art has the related preparatory drawing.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Encounters with the 1930s

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain presents Encounters with the 1930s, on view 2 October 2012–7 January 2013.

Encounters with the 1930s is the Museum’s contribution to the commemorations marking the 75th anniversary of the creation of Guernica (1937), Pablo Picasso’s emblematic art work.

Max Beckmann, Paris Society, 1931. Oil on canvas, 109,2 x 175,6 cm., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

The show, jointly organized by the Museum’s Departments of Collections and Exhibitions, will occupy a surface of more than 2,000 square meters divided into two areas. The first, on the second floor, will contain part of the permanent collection, with Guernica as the central point of the itinerary. The other section, on the first floor, will analyze the paths traced by artists in their interpersonal and international relationships while seeking to spur their creativity.

Vasily Kandinsky. Succession, 1935 © Vassily Kandinsky,

VEGAP, Madrid, 2012

The show is made up of more than four hundred exhibits from prestigious institutions around the world, both Spanish (IVAM, Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña, Filmoteca Nacional, Filmoteca de Cataluña, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Residencia de Estudiantes, the collections of the Museo Reina Sofía, etc.) and foreign (Centre Georges Pompidou; Pushkin Museum [Moscow]; MoMA, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum [New York]; National Gallery of Art [Washington, D.C.]; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Metropolitan Museum [New York]; The Wolfsonian-FIU; International Center of Photography [New York]; Nationalgalerie [Berlin], etc.).

Some of the most important artists of the 20th century will be represented, including Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy, Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, Max Beckmann, Robert Delaunay, André Masson, Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, Luis Buñuel, Joaquín Torres-García, Hans Arp, Fernand Léger, René Magritte or Mario Sironi and many others. The exhibition will also be a unique opportunity to see pieces that are visiting Spain for the first time, such as

Antonio Berni‘s New Chicago Athletic Club (1937) or

Wolfgang Paalen‘s Combat des princes saturniens II.

Based on the results of a collective investigation, the exhibition aims to redefine the conceptual and historical parameters of a fundamental period of the 20th century, essential for a full understanding of our own times. Yet to be studied in sufficient depth, this was a time of conflict when art and power came into confrontation and mutual support. Although cloaked in an appearance of eclecticism, this was nevertheless a phase when art was enabled to question its own postulates. In addition, the thirties constitute an essential period for the Museo Reina Sofía itself, since they form the fundamental axis of the permanent Collection, with Guernica as its center of gravity.

Although this is not the first exhibition on the subject of the thirties, it is the first to propose an “episodic” view of the decade that prioritizes connections between artists and moments of stylistic eclecticism.

Encounters with the 1930s has a six-part structure: Realisms; Abstraction; Exhibition culture: National and international projects; Surrealism; Photography, Film and posters; Spain: Second Republic, Civil War and Exile. Each of these sections encompass the main preoccupations and problematics which marked the decade from a political, aesthetic and cultural viewpoint, constituting a point of encounter which, in Mendelson’s words, has to be “interpreted openly in order to reveal the roads leading to an understanding that personal relationships and tensions between artists constituted the prime underlying framework for experimentation.” The aim is to present this troubled and exciting period not only on the basis of propaganda narratives but also through the ways found by the artists themselves to trace their own paths through an atmosphere of growing violence.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

52 Santa Isabel Street

28012 Madrid

www.museoreinasofia.es

ON THE THIRTIES

The decade in question is characterized by the rise of totalitarian governments which used the support of the arts to “coordinate a narrative of creativity that was frustrated by the requisites of power and the monumentality of the State,” explains Jordana Mendelson. At the same time, many artists who were working under the auspices of public institutions even managed to find ways to hinder the progress of the tasks they had been assigned, while others, who defended the singularity of the artist’s voice, placed their talents at the service of government organizations or used advertising as a tool for reaching the masses. Artists thereby demonstrated, Mendelson concludes, that both aesthetic conformity and nonconformity could challenge or overthrow the established order.

The decade of the thirties is marked by the Wall Street crash of 1929, the subsequent worldwide depression, the need for artists to confront a new economic and political reality, and a hitherto unknown development of communications under the impulse of technological innovation in publishing and the media. Mass production and the extension of transport networks enabled patterns of consumption to reach the most remote places. Artists were by no means unaffected by all this, and made use of such novelties to disseminate their works, manifestoes and personal letters. Political ideas were thus transmitted with the same speed, and objects and theories crossed borders.

The circuits followed by artists in the thirties were not linear, since they were as well versed in abstract art as in realism and surrealism. Although these three trends dominated the visual arts, there were moments of fracture, idiosyncratic episodes and microhistories which the curator sees as indicative of an enormous richness. It is in these eclectic and local histories of individual artists, open to numerous interpretations, that “we find an exquisite manifestation of the disconcertedness, the frustration and the intimidation sensed by anyone who tries to pigeonhole the thirties within a single definition.” This exhibition therefore tries to present a demythified view of the thirties by showing works that exemplify visual complexity, technical dexterity and conceptual profanity, allowing them to be analyzed as individual pieces but contextualized at the same time within an interrelated history.

REALISMS

The opening section of the exhibition juxtaposes works by artists who were fascinated by cultural conflict. Despite their different geographical origins, styles, political affiliations and artistic training, they transcended these differences in foregrounding such dominant themes as portraiture, work and leisure, everyday life (urban scenes and rural environments) and so on. Some chose woman as an artistic object (Togores), made the body expressive of something other than aesthetic appearance (David Alfaro Siqueiros), or underscored their commitment to the working classes (Stanley Spencer and Ben Shahn).

The variations in realism during the decade demonstrate that there was an interest, a dedication and an urge to explore in painting that surpassed the directives of any theory or controversy. As Jordana Mendelson says, the different artistic disciplines “resorted to realism in the period between the wars to indicate the desire of artists to reach the largest possible public, even when those viewers were divided, or at least differentiated, by class interests or political commitments.” Among the works on display in this first part of the exhibition are pieces by Alfaro, Guston and Beckman, as well as a work by Berni which has traveled to Spain for the first time from the MoMA in New York.

ABSTRACTION

In the thirties, the perseverance of abstraction as a form of creative investigation transformed the movement from purely Utopian reflection into a number of controversial positions, often locally motivated, whose supporters found themselves trapped in the crossfire of the debates on form and politics. The bridge between Europe and the United States was forged by international travel and political commitment.

During this period, the biomorphic forms of Hans Arp proved more attractive than ever to international artists, especially those who combined abstract art with surrealism (Barbara Hepworth, Marinel·lo). For his part, Moholy-Nagy, who exerted a decisive influence in photography, film and abstract art, transferred his experiments with light, movement and design from Europe to the United States. Josef and Anni Albers were to have a comparable impact on Black Mountain College, a center for experimentation in the humanities which congregated artists like John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg.

Joaquín Torres García is the clearest example of an artist who contributed decisively to the abandonment by abstract art of the European formula of manifesto-statements and its arrival on the American continent as a genuine revelation. The artist opened up new paths for abstract art with the publication in Montevideo of the journal “Círculo y Cuadrado” and the foundation of the Escuela Taller de Artes Plásticas.

Ad Reinhardt was meanwhile one of the artists in the American Abstract Artist group whose work illuminated the impact of the Spanish Civil War and Spanish artists on the development of experimental abstract art in the United States. Besides pieces by some of the artists mentioned, this section moreover features works by Klee, Baumeister, Kandinsky, Calder, Mondrian and Hans Arp. Color Box (1935), by Len Lye, will also be projected in the same room.

EXHIBITION CULTURE: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL PROJECTS

In the thirties, exhibitions constituted settings on a grand scale which manifested the role of artists as contributors to government projects, both for a domestic public and for display outside the country.

By means of art works, decorative projects and documentary material, this part of the exhibition documents events like the 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris, the Mostra Fascista (Italy, 1933), the 1937 International Exposition in Paris, and the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Of special interest is the way in which artists were recruited to create a national image for exhibition pavilions, and their contribution to the general design of fairs and propaganda materials.

Besides the great international expositions, this section also looks at those which served as counterpoints or “responses” to the national projects of the large-scale exhibitions. Various projections will also be shown on the Paris Pavilion of 1937 and the New York World’s Fair, 1939-40.

SURREALISM

The international expansion of the surrealist movement in the thirties guaranteed its influence on the work of certain experimental artists and on commercial culture. André Breton became the arbiter of orthodoxy within the movement. From the beginning of the decade, and after the exhibitions organized by the Julien Levy Gallery in New York (Surrealism, 1932) and the MoMA (Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, 1936), the movement rapidly rose and culminated, the curator says, with the erotic dream of the Venus Pavilion designed by Dalí for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

This section is based on the international exhibitions on surrealism held in the course of the decade: Tenerife (1935), London (1936), Paris (1937) and Mexico (1940), in which artists with a considerable reputation at the time, such as Miró, Arp, Picasso and Ernst, were mingled with representatives of “local factions”, such as Toyen, Frida Kahlo, Henry Moore and Wilhelm Freddie. Such juxtapositions are described by the curator as “surprising”.

Two decisive events are held up as challenges to the hegemony of Breton. The first is Dalí’s collaboration with gallerist Julien Levy, and the other is the Exposició Lògicofobista in Barcelona, which included work by young artists like Remedios Varo, Joan Ismael, Antoni García Lamilla and Leandre Cristòfol. Joan Miró, an artist who took part both in the official exhibitions held at that time under the auspices of Breton and in those organized by the MoMA, nevertheless maintained his independence.

Works by Breton, Oscar Domínguez, Benjamín Palencia, Magritte, Picasso, Masson, Matta, Ferrant and Dalí are accompanied in this section by a projection which documents an exhibition on surrealism organized by the MoMA in 1936. Appearing in it are works by Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Salvador Dalí and other artists.

PHOTOGRAPHY, FILM AND POSTERS

In the thirties, photography joined the stream of mass culture, and the marginal position of amateur photographers was superseded by the prominence accorded to prestigious artists. The period saw an increase in the number of photographic yearbooks and in the collaboration of professionals with fashion magazines (such as Man Ray’s work for Vogue). At the same time, retrospectives on the discovery of photography were organized and accompanied by chronicles written by first-rate critics (like Walter Benjamin and Lucia Moholy). Documentary photography also dominated the pages of journals and, in Mendelson’s words, “was used by governments to create evidence that would justify reforms and social critique.”

The discipline was conditioned by forced or voluntary migration. A large number of talented European and American photographers traveled from one place to another, developing facets of their work related to advertising or journalism. The emergence of illustrated magazines contributed to this. In the meantime, experiments with typography, collage and photomontage made it possible for artists to create new forms.

Many of those who dominated the art of photography also cultivated that of the cinema camera (Walker Evans, Moholy-Nagy, Paul Strand). Documentary films became immensely popular during the thirties, leading to the use of public funds by governments to create film and photography units. Artists experimented in these disciplines with realism, surrealism and abstract art.

As regards posters, special mention is merited by the graphic designer Josep Renau, who argued publically throughout the thirties for the use of the new media and technologies in the representation of politically relevant subjects. As the curator of the exhibition explains, Renau “invoked the necessity for a new kind of Realism which would relate the political tragedy of the time to a suitable form of mass representation (…) Renau’s treatise, published in 1937, is one of the most exhaustive and energetic defenses of the need to combine avant-garde experimentation, political commitment and commercial initiative.” Paul Strand, Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy and Rodchenko are among the artists represented in this section, which is completed with the projection of Walker Evans’s Travel Notes (Tahiti, 1937) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

SPAIN: SECOND REPUBLIC, CIVIL WAR, EXILE

The second floor of the Museum will house this section, which brings the exhibition’s itinerary to a close. It is made up of three fundamental areas corresponding to the Republic, the national and international vision of the Civil War, and exile.

The second floor of the Museum will house this section, which brings the exhibition’s itinerary to a close. It is made up of three fundamental areas corresponding to the Republic, the national and international vision of the Civil War, and exile.

It is well known that Spanish artists played a very active part in the creative practices of the period. Many went into voluntary or forced exile after the Civil War. Also, however, a large number of foreign artists were exiled in Spain after having to leave their countries. Among the illustrious names who settled in or passed through the Iberian Peninsula were Diego Rivera, Jacques Lipchitz, Calder, Margaret Michaelis, André Masson, Mariano Rawicz and Mauricio Amster. All of them must be taken into account when it comes to understanding the complexity of modern art in Spain. Spanish artists entered into dialogues with their international colleagues, and their works were created and judged in accordance with similar criteria. Nevertheless, as the curator of the exhibition explains, “the history of the absence of a solid market for experimental art and the general intolerance of the Spanish public toward the avant-garde is a history of resistance to the visual practices of the foremost contemporary artists.” Even so, this does not mean that the avant-garde was completely absent from Spain, since international artists visited the country and took part in some of its major exhibitions.

Mendelson speaks of an “alternative history of the avant-garde” which would include, for instance, Alberti’s narratives in the magazine “Luz” (in which he wrote of his meetings with artists and intellectuals from the Soviet Union), the montages of Josep Renau published in the magazine “Octubre”, and Ernesto Jiménez Caballero’s book “Circuito imperial” (1929), which relates the author’s journeys through Mussolini’s Italy. Also of interest are the work produced by Diego Rivera and Lipchitz, the influence of Ibiza on the work of Walter Benjamin and Raoul Hausmann, the collaboration of Eli Lotar with Buñuel on the film Las Hurdes: tierra sin pan, the performance of Calder’s circus for ADLAN in Barcelona, the creation of the Mercury Fountain by the same artist for the 1937 Pavilion, the influence of Le Corbusier on GATEPAC, Man Ray’s photographs of the architecture of Barcelona, and the involvement of international artists in the production of propaganda during the Spanish Civil War.

In Encounters with the 1930s, it is sustained that these works are not exceptional but characteristic of the experience of modernity and the avant-garde in Spain. “They show us other ways of describing contemporary art in relation to Spain,” says Jordana Mendelson. “Spanish artists would thus be inscribed within the broader narrative of art in the thirties, which stresses the different media expressions of modernity in the visual arts, and amplifies it to cover a multimedia and interdisciplinary framework.”

The itinerary of this section brings visitors in turn to the following rooms: Cinema; Scenography and the visual arts in the Second Republic; The satirical war drawing; Visions of War and Rearguard; Eclectic modernity; Spanish art in the Republic; The Spanish Pavilion of the Republic, 1937; Aidez l’Espagne!; André Masson; The international press on the conflict in Spain; Resonances of the Telluric in the Spanish exile.

Paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, posters, journals and films will help visitors to understand the art of the time in its internal and external relation to Spain, as well as the events taking place in the country.

Works by Alberto Sánchez, Picasso, Miró, Masson, Adam Smith, Lipchitz, Catalá Pic, Marinel·lo, Cristòfol, Torres García, Julio González, Ortiz Echagüe, Philip Guston, Grosz, Le Corbusier, Magritte, Jove-Pau, Chauvin, Luis Fernández, Esteban Francés, Quintanilla, Remedios Varo, Renau and others will be displayed in this section, which will also devote an area to the cinema (for instance, there will be a screening of Jaume Miravilles’s 1936 film El entierro de Durruti).

An important part of Encounters with the 1930s is the one related to international exhibitions. One of the most important was the one organised in Paris in 1937. The Museo’s collection dedicates, on the second floor, some galleries to the works present in the Spanish Pavilion, with Guernica as central axis. The exhibition presented intends to widen this discourse, but with a different reading, in relation to the narrative of the galleries on floor 1. This section opens with a gallery dedicated to theatre. Specifically with the curtains that the artist Alberto Sánchez made for La romería de los cornudos (1933), a ballet piece starring La Argentinita. It is one of the jewels of the Museo’s collection that hadn’t been on display since the exhibition dedicated to Alberto 12 years ago. The important and large loan made by La Argentinita’s family complements this work. Besides, the show gathers several examples of the different initiatives that the Second Republic established in relation to theatre, such as the group La Barraca, the Pedagogic Missions, the national ballets, etc. It is noteworthy that the link between the visual avant-gardes and theatre is a line of investigation that has always interested the Museo and that will develop in the future. In this part of Encounters with the 1930s it becomes a transversal subject, highlighting the importance of theatre during the Second Republic, maintained during the years of the Civil War and exile —this fact is underlined in the galleries dedicated to political theatre, undertaken in the streets during the conflict—, and also its prominent presence in the 1937 Pavilion —for which specific commissions supporting the Republic— and exile, as it became one of the ways of expression used by many exiled Spanish artists, such as Alberto Sánchez or Esteban Francés.

Continuing with the Republican phase, the show underlines the government’s support to the artistic modernity of the time and its wish to internationalise. One of the galleries includes works by different groups and movements, such as constructivism, the Escuela de Vallecas, GATEPAC, ADLAN or the School of Paris. The pieces of these artists, organised around publications and exhibitions, show the great eclecticism of Spanish art during the decade. Another line of force in Encounters with the 1930s is Goya and his influence as an icon of Civil War, especially, through the Desastres de la Guerra. On the one hand, this artist’s presence was very relevant in the 1937 Pavilion, where a special edition of this series was available for purchase. On the other, the Republic used these works as central axis for several exhibitions organised abroad to raise money. The influence that both Goya and his Desastres de la Guerra had in many artists is depicted in the galleries of the show. In the Civil war area there’s a room dedicated to Realisms, one of the most used genres during this time, due to the urgency to convey messages. Realism is depicted both in its Soviet and its political —closer to the avant-gardes— facets. Also remarkable is an important series of drawings made by Alberto for the Nueva cultura magazine that proceeds from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. It is the first time these works are shown in Spain, along his well-known piece Ríos de sangre.

Satirical drawing was also of great importance during the conflict. It occupies one of the first galleries, in which a collection of etchings by Francis Bartolozzi, shown here for the first time.

The section dedicated to the 1937 Pavilion gathers commissions specifically made by the Republic to great avant-garde artists that were living abroad, such as Julio González, Picasso or Miró.

The international aspect of the conflict, that is, how the Spanish Civil War was perceived and depicted outside Spain, is documented through abundant editorial material, produced to support and publicize the Spanish cause. In this sense the David Smith’s Medallas del deshonor is noteworthy, as is René Magritte’s Le drapeau noir (1936–37), proceeding from the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. Besides, a monographic room has been dedicated to André Masson’s work in relation to Spain, where the artist lived for two years (just before the conflict and during the first years of the war).

This space, which contains most of his works of this period, based on his experience, has been possible thanks to the important loan made by his family.

The exhibition continues with several covers dedicated to Spain which were published by three major magazines of the time (AIZ – Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, Vu and Regards). Lastly, a room on exile shows, among others, three important pieces recently purchased by the Museo: one by Esteban Francés and two by Remedios Varo. This section features the prominent portraiture of artists related to the international Surrealist trend. Luis Buñuel’s film Los Olvidados (1950), shot during his exile in Mexico, is the final piece of the show.

MAJOR LOANS

One especially noteworthy aspect of the organization of this exhibition is the large number of short-term and long-term loans and donations that have been secured by the Museum, after months of hard work and intense negotiations, in order to elaborate the show’s intended discourse.

Attention should be drawn in particular to an important loan from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, which will enable a remarkable set of satirical drawings, made for the “Nueva Cultura” magazine by Alberto Sánchez (Toledo, 1895-Moscow, 1962) to be exhibited in Spain for the first time.

Thanks to an extraordinary long-term loan of a set of nearly 50 works by the family of André Masson (Balagny-sur-Thérain, 1896-Paris, 1987), the exhibition will include a monographic area that explains this artist’s relationship with Spain. On display will be a selection of these works, produced during his stay in Spain between 1931 and 1939, including a number of drawings made during his stay in Tossa de Mar and published in the magazine “Acéphale”, works from the series Massacre, twelve from the series Tauromaquia, and various satirical drawings, photographic works, designs for flags for the International Brigades, and other items.

The last of these major international loans is that made by The Estate of David Smith. This consists of the so-called Medals of Dishonor, a group of fifteen bronze reliefs strongly imbued with social critique, which were first exhibited by the American sculptor in 1940. The daughter of César Domela (Amsterdam, 1900-Paris, 1992) has meanwhile made a long-term loan to the Museum of the only known copy of the painter’s propaganda poster entitled Des armes pour l’Espagne antifasciste, 1937, one of the most outstanding graphic works created specifically to aid the Republican cause.

Also significant is the exceptional bibliographic set on the 1930s (mainly magazines and books) from José Mª Lafuente’s collection, related to the Spanish Civil War, its reception abroad, and exile.

Other major long-term loans illustrate the Republic’s collective initiatives in the field of theatre and dance. These include pieces lent by the Fundación Argentinita y Pilar López (Madrid) and the Fundación Federico García Lorca, including photographs of the La Barraca theatre company; material from the Museo Nacional del Teatro (Almagro, Ciudad Real), including documentary and photographic records of the Pedagogical Missions and La Barraca; and loans from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport’s Centro de Documentación Teatral, INAEM, and from the Museo Galego de Arte Contemporáneo Carlos Maside, as well as one by the Residencia de Estudiantes which includes a set of images of the Pedagogical Missions.

The permanent Collection are of Encounters with the 1930s will gather several of the works that were to be seen at the Spanish Pavilion in the 1937 Universal Exposition in Paris. Among them are six etchings by Francis Bartolozzi (Madrid, 1908-Pamplona, 2004), recently acquired by the Museo Reina Sofía, and complemented here with a long-term loan by the Museo de Navarra and the painter’s family that also includes various pieces by her husband, Pedro Lozano (Pamplona, 1907-1985). In the meantime, the Museo del Traje- CIPE has ceded eight period copies of photographs taken by José Ortiz Echagüe (Guadalajara, 1886-Madrid, 1980), while the Museo Ramón Gaya in Murcia is contributing work by this Murcian painter. Also contributing is the Colección Zorrilla Lequerica with the loan of one of the painter Luis Fernández’s most emblematic works. Finally, pieces by the painters Emiliano Barral (Sepúlveda, Segovia, 1896-Madrid, 1936) and Jesús Molina García de Arias (Cerecinos de Campos, 1903-Madrid, 1968) have joined the Museo’s permanent Collection thanks to donations made by their respective families.

CATALOGUE

Besides a text written by the curator of the exhibition, Jordana Mendelson, the following authors also write in the catalogue on various aspects of the show: Belén García Jiménez, Alicia Alted Vigil, Juan Manuel Bonet, Robin Adèle Greeley, James Oles, Janine Mileaf, Javier Pérez Segura, Jeffrey T. Schnapp, Juan José Lahuerta, Jutta Vinzent, Karen Fiss, Katarina Schorb, Robert S. Lubar, Rocío Robles Tardío, Romy Golan and Tyrus Miller. Completing the publication, which was co-published with La Fábrica, are color reproductions of the works on display.

Portrait of Spain: Masterpieces from the Prado

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has announced that more than 100 masterworks from one of the world’s most renowned collections of European painting will be presented at the MFAH beginning December 16, 2012, in Portrait of Spain: Masterpieces from the Prado. The exhibition—on exclusive U.S. loan in Houston as part of a new initiative by the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid to broaden access to its holdings—tells the story of the evolution of painting in Spain from the 16th through 19th centuries and explores how artists reflected the sweeping changes in society, culture, politics and religion that contributed to the development of a modern Spanish identity. Portrait of Spain opened July 21 at the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, Australia, the first stop on this two-venue tour.

“Portrait of Spain will bring to U.S. audiences an extraordinary panorama of courtly and religious paintings by some of the greatest European artists—above all the Spanish masters such as Goya and Velázquez, but also foreign luminaries who worked for the Spanish court, including Rubens and Titian,” commented MFAH Director Gary Tinterow. “This exhibition marks the first time that the Prado has lent so extensively to an American institution. It is a wonderful privilege for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, to have this exclusive U.S. showing, and I am especially looking forward to presenting these iconic paintings to our communities.”

“Nothing quite illustrates Spain’s rich tradition of arts and culture like the Prado, one of the finest museums in the world,” said BBVA Compass President and CEO Manolo Sánchez. “That's why BBVA Compass seized the opportunity to sponsor this exhibit. As part of the BBVA Group, which is headquartered in Spain, we are proud to help bring it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and excited for the city to experience some of Europe’s greatest painters.”

Exhibition Dates

Portrait of Spain: Masterpieces from the Prado will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from December 16, 2012, through March 31, 2013.

Exhibition Overview

Portrait of Spain, exhibited in the second-floor galleries of the Audrey Jones Beck Building at the MFAH, will be installed according to themes within three distinct eras of Spanish history: 1550 to 1770; 1770 to 1850; and 1850 to 1900. Masterpieces by the leading painters of the day from each of the four centuries include works by Francisco de Goya, El Greco, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Jusepe de Ribera and Diego Velázquez. Artists who worked for the royal court and directly influenced the development of painting in Spain are also well represented, with superb paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo and Titian.

1) “1550–1770: Painting in an Absolutist State”

Outstanding portraits, mythological scenes, devotional paintings and still lifes by artists including El Greco, Diego Velázquez and Francisco de Zurbarán exemplify the splendor of Spain’s Golden Age, when the empire was at the zenith of its global power, and offer a glimpse of courtly life under the expansionist Habsburg (1516–1700) and later the Bourbon (1700–1808) monarchs, who ushered in the Enlightenment to Spain. The use of portraiture and mythological themes as expressions of royal power; the role of religious imagery in painting; and the symbolism employed in still-life imagery to espouse the virtues of a civil society all factor in the development of Spanish painting during this time.

The Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia and Magdalena Ruiz,Alonso Sánchez Coello. 1585–88, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Diego Velázquez, El bufón don Diego de Acedo, “el Primo”, ca. 1636-1638, oil on canvas, 42 1/8 x 32 5/16 in. (107 x 82 cm). Museo Nacional del Prado.

Diego Velázquez’ Workshop, Retrato orante de Mariana de Austria, ca. 1655, oil on canvas, 82 5/16 x 57 7/8 in. (209

Diego Velázquez, King Philip IV (1605–1665) in Hunting Garb, circa 1635, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Diego Velazquez Mars

Antonio de Pereda The Relief of Genoa (1634-35),

Diego Velazquez, The Surrender at Breda (1634-35).

Juan Carreno De Miranda The Monster 1680.

Vicente López y Portaña, Señora Delicado de Imaz

Pleasure and pride ... Juan van der Hamen y Leon

Francisco de ZurbaranMartyrdom of Saint James (c.1640)

2) “1770–1850: A Changing World”

Against the tumultuous backdrop of the French Revolution; the Napoleonic Wars and France’s invasion of Spain; and the onset of a series of devastating civil wars, Spanish artists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries turned to chronicling a variety of levels of Spanish society. Preeminent among the artists during this unpredictable time was Francisco de Goya, who was painter to the courts of Charles IV and Charles V and who later in life graphically depicted the casualties of war and madness.

In this exhibition, Goya’s work is represented by major Neoclassical portraits, including those of

Manuel Silvela

and the Marquesa de Villafranca,

and an important selection of prints from the artist’s three extraordinary series: Los Caprichos, Los Disparates and Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War).

Francisco de Goya, Tadea Arias de Enríquez, ca. 1789, oil on canvas, 74 13/16 x 41 ¾ in. (190 x 106 cm). Museo Nacional del Prado.

3) “1850–1900: The Threshold of Modern Spain”

Following the civil wars, the emergence of a fledgling Spanish national identity in the mid-19th century was supported by a period of relative economic prosperity. A move toward Romanticism brought with it a focus on genres that reflected the ideals of middle-class taste of the period, including landscapes, portraits, historical and religious scenes and nudes. Featured in this section are the works of Federico de Madrazo, known for his history painting and his portraits (and as a onetime director of the Prado); Eduardo Rosales, who looked back to Diego Velázquez in pursuit of a new Realism in Spanish painting; Mariano Fortuny, whose fascination with Orientalist themes reflected his exotic travels and international career; Aureliano de Beruete, one of the earliest Spanish painters to identify with the Impressionist movement; and Joaquín Sorolla, whose Realist paintings depicting the lives of fishermen and farmers explored the effects of sunlight and shadow and pushed Spanish painting toward the threshold of modernity.

Eduardo Rosales Gallinas Female Nude (after bathing) (c. 1869)

Picasso La Belle Hollandaise (1905)

Read more about the show here

Exhibit List

1550 - 1770. Painting in an absolutist state

1.1. Portriat and Power: Kings and Buffoons

1. Doña Juana de Austria

Antonio Moro

Oil on canvas, 195 x 105 cm

1560

2. Isabel Clara Eugenia and Magdalena Ruiz

Alonso Sánchez Coello

Oil on canvas, 207 x 129 cm

1585 – 1588

3. Philip IV as a Hunter

Diego Velázquez

Oil on canvas, 189 x 124 cm

c. 1635

4. Empress Margarita de Austria

Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo

Oil on canvas, 205 x 144 cm

1666

5. Charles II in Armour

Juan Carreño de Miranda

Oil on canvas, 232 x 125 cm

1681

6. Louis I, Prince of Asturias

Michel-Ange Houasse

Oil on canvas, 172 x 112 cm

1717

7. Charles IV, Prince of Asturias

Antón Rafael Mengs

Oil on canvas, 152 x 110 cm

c. 1765

8. The Duke of Pastrana

Juan Carreño de Miranda

Oil on canvas, 217 x 155 cm

c. 1666

9. Don Tiburcio de Redín

Fray Juan Ricci

Oil on canvas, 203 x 124 cm

1635

10. Francisco Lezcano, “The Boy from Vallecas”

Diego Velázquez

Oil on canvas, 107 x 83 cm

1635 – 1645

11. Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, ''The Monster'', dressed

Juan Carreño de Miranda

Oil on canvas, 165 x 107 cm

c. 1680

12. Democritus (?)

José de Ribera

Oil on canvas, 125 x 81 cm

1630

13. Portrait of a Buffoon with a Dog

Velázquez’s Workshop

Oil on canvas, 142 x 107 cm

c. 1645

1.2. Mythology as the Language of Power

14. The Relief of Genoa

Antonio de Pereda

Oil on canvas, 290 x 370 cm

1634 – 1635

15. Hunting in Aranjuez

Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo

Oil on canvas, 187 x 249 cm

XVII Century

16. Hercules and the Dog Cerberus

Francisco de Zurbarán

Oil on canvas, 132 x 151 cm

1634

17.Vulcan Forging the Thunderbolts of Jupiter

Pedro Pablo Rubens

Oil on canvas, 181 x 98 cm

1636 - 1639

18. Flora the Goddess

Luca Giordano

Oil on canvas, 169 x 109 cm

c. 1697

19. The Olympus: Battle with Giants

Francisco Bayeu y Subías

Oil on canvas, 68 x 123 cm

1764

1.3. Painting and Religion: Sacrifice, Intimacy and The Saint as Hero

20. Christ carrying the Cross

Tiziano

Oil on canvas, 67 x 77 cm

c. 1565

21. The Holy Visage

El Greco

Oil on canvas, 71 x 54 cm

1586 - 1595

22. Christ, Man of Sorrows

Antonio de Pereda y Salgado

Oil on canvas, 97 x 78 cm

1641

23. The Dead Christ Held by an Angel

Alonso Cano

Oil on canvas, 137 x 100 cm

1646 - 1652

24. Reclining Christ

Juan Antonio de Frías y Escalante

Oil on canvas, 84 x 162 cm

1663

25. Christ on the Path to Calvary

Juan de Valdés Leal

Oil on canvas, 167 x 145 cm

26. Prayer in the Orchard

Giandomenico Tiepolo

Oil on canvas, 125 x 142 cm

1771 - 1772

27. The Immaculate Conception of Aranjuez

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Oil on canvas, 222 x 118 cm

1670 - 1680

28. The Annunciation

Francisco Rizi

Oil on canvas, 112 x 96 cm

c. 1665

29. The Holy Family

Vicente Carducho

Oil on canvas, 150 x 115 cm

1631

30. The Adoration of the Shepards

Pedro de Orrente

Oil on canvas, 111 x 162 cm

c. 1623

31. Saint Benedict

El Greco

Oil on canvas, 116 x 81 cm

1577 – 1579

32. Saint James the Elder

José de Ribera

Oil on canvas, 202 x 146 cm

1631

33. James’ Martyrdom

Francisco de Zurbarán

Oil on canvas, 252 x 186 cm

c. 1639

34. The Penitent Saint Jerome

José de Ribera

Oil on canvas, 77 x 71 cm

1652

35. The Death of Mary Magdalene

José Antolínez

Oil on canvas, 205 x 163 cm

c. 1672

36. The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Oil on canvas, 123 x 162 cm

1675 - 1682

37. Saint Matthew and Saint John the Evangelist

Juan Ribalta

Oil on canvas, 66 x 102 cm

1675 - 1682

1.4. Civil Society: The Still Life