Saturday, December 15, 2012

Becoming Picasso: Paris 1901

The Courtauld Gallery's exhibition Becoming Picasso: Paris 1901, on view February 14 to May 26, 2013, tells the remarkable story of Pablo Picasso’s breakthrough year as an artist – 1901. It was the year that the highly ambitious nineteen-year-old first launched his career in Paris at a debut summer exhibition with the influential dealer Ambroise Vollard. Refusing to rest on the success of this show, Picasso (1881-1973) charted new artistic directions in the second half of the year, heralding the beginning of his now famous Blue period. Becoming Picasso focuses on the figure paintings of 1901 and explores his development during this seminal year when he found his own artistic voice. This exhibition is a unique opportunity to experience works, now considered to be Picasso’s first masterpieces, which established his early reputation. They are also among the earliest paintings to bear the famously assertive and singular Picasso signature, which he adopted in 1901.

1901 was a momentous and turbulent year for the young Picasso. He spent the first part of it in Madrid where he helped to set up Arte Joven, an avant-garde journal with ambitions to shake up the staid culture of the Spanish capital. This role could not hold him for long as Picasso’s sights were firmly set upon becoming a great painter in Paris, the ‘capital of the arts’. His first visit to Paris, in the autumn and winter of 1900, had fuelled his ambitions and led to the prospect of the 1901 exhibition with Vollard, one of the city’s most important modern art dealers. In February 1901, whilst still in Madrid, Picasso received news from Paris that his close friend, Carles Casagemas, had committed suicide in dramatic fashion. Casagemas shot himself in Montmartre’s Hippodrome café in front of the young woman who had jilted him and his friends. The tragedy would have a profound impact upon Picasso’s art as the year unfolded.

Picasso left Spain for Paris, probably at the beginning of May, with a clutch of drawings and just a few paintings. He had little over a month to produce enough work for his Vollard exhibition. Arriving in Paris, Picasso took a studio in Montmartre at 130ter boulevard de Clichy with Pere Mañach who acted as his agent. The studio had previously been occupied briefly by Casagemas before his suicide. Picasso then painted unstintingly, sometimes finishing three canvases in a single day. This outpouring of creative energy resulted in most of the sixty-four works shown at the Vollard exhibition (24 June to 14 July). They demonstrate Picasso taking on and reinventing the styles and motifs of major modern artists, including Van Gogh, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec. In works such as

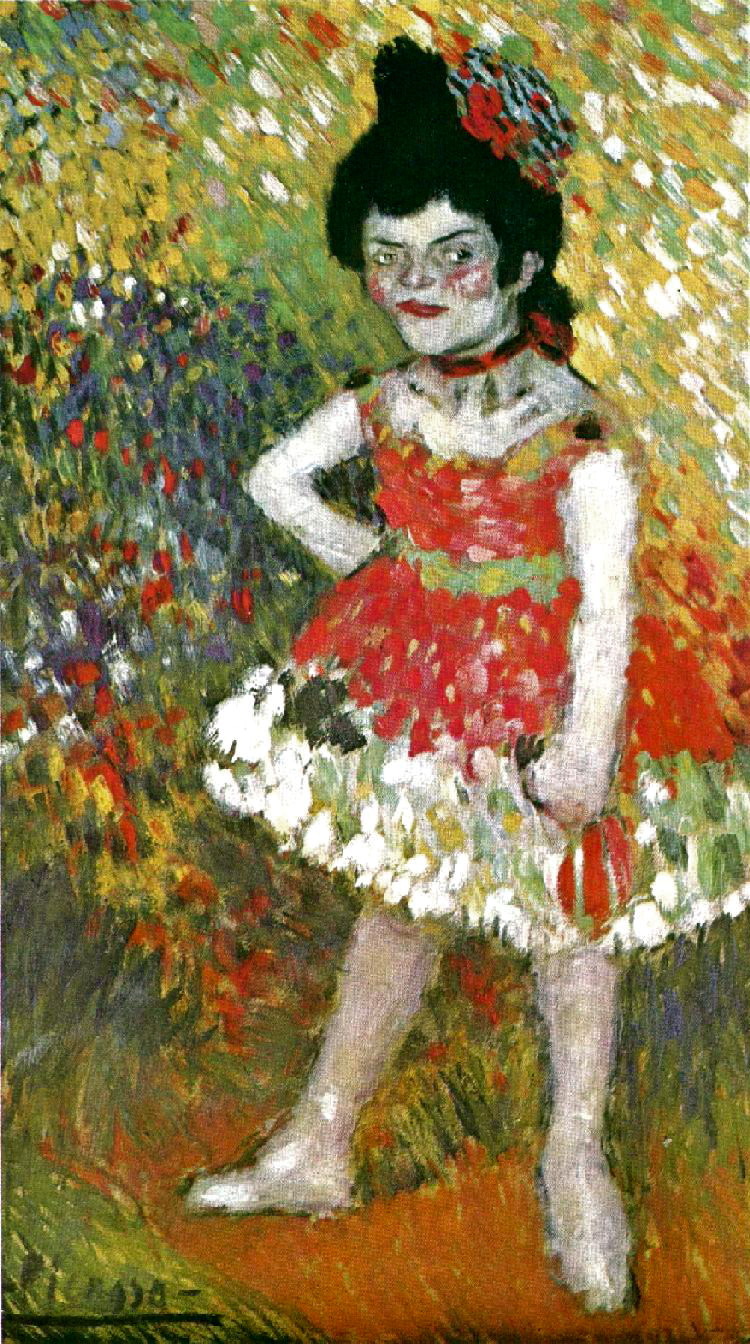

Dwarf-Dancer, Museu Picasso, Barcelona,

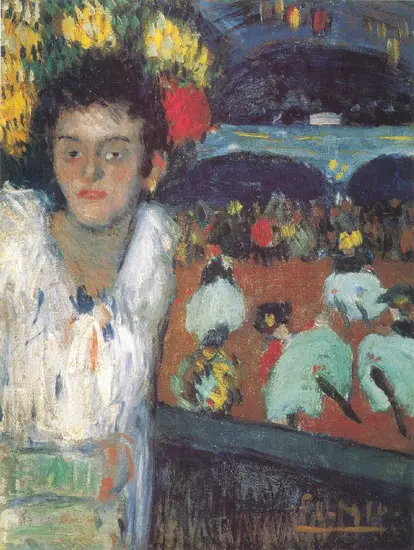

and At the Moulin Rouge, Private collection,

we see these influences coming together and being transformed into bold and daring expressions of Parisian night life, captured in showers of broken brushwork and bright colours.

The Vollard exhibition was a critical success with respectable sales. Reviewers were won over by Picasso’s youthful energy, creative powers and insatiable visual appetite. As Gustave Coquiot introduced him: “Pablo Ruiz Picasso – an artist who paints all round the clock, who never believes the day is over, in a city that offers a different spectacle every minute… A passionate, restless observer, he exults, like a mad but subtle jeweller, in bringing out his most sumptuous yellows, magnificent greens and glowing rubies”. The exhibition effectively launched Picasso’s career in Paris but, despite this success, he took his art in daring new directions in the second half of 1901.

Picasso evidently wanted to move away from the belle époque gaiety of the Vollard show paintings, with their exuberant brushwork, towards pictures that expressed a more profound and reflective account of human existence. He was inspired, in part, by the spectre of Casagemas’ death.

The Blue Room, Phillips Collection, Washington, is often thought to mark a turning point, demonstrating Picasso’s move to the use of more muted colours, tending towards blue, and painted outlines to enclose form, giving his figures an almost sculptural effect. These qualities are a defining feature of the celebrated series of paintings of melancholic café drinkers, numbed by ennui and absinthe, which are now considered one of his greatest early achievements.

This exhibition brings together a number of major examples including

Absinthe Drinker, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg,

which is redolent of

Degas’ infamous earlier treatment of the subject.

In other café scenes, such as

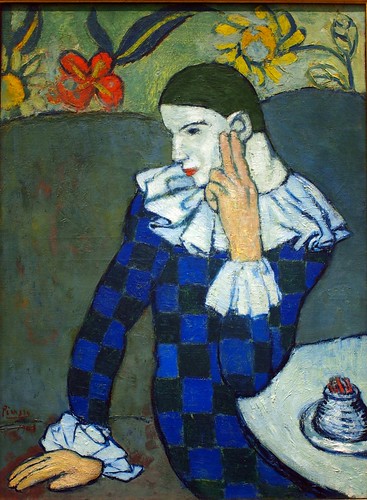

Seated Harlequin, (above) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

and Harlequin and Companion, The State Pushkin Museum, Moscow,

Picasso introduces the unexpected figure of Harlequin, reinventing this familiar subject in a highly original manner. This is the first appearance of the mischievous Harlequin in Picasso’s paintings. The character became a recurrent feature of his later art and indeed was adopted as an alter ego for the artist.

Related to this group is Picasso’s much-loved

Child with a Dove, Private collection,

which also expresses a sense of melancholy but in relation to the fragility of childhood innocence.

This series of works anticipate his Blue period paintings of the following few years. They demonstrate the early emergence of a number of major themes that preoccupied the young Picasso in the second half of 1901 and would continue to drive his art throughout his long career. The paintings explore the interplay between innocence and experience, purity and corruption, and life and death. These concerns were bound up with Casagemas’ death and further inspired by a number of visits Picasso made in the late summer and autumn of 1901 to the Saint-Lazare women’s prison where he observed, and subsequently painted, the former prostitutes and their infants who were incarcerated there.

Picasso’s new pictorial world of innocence and corruption, of prostitutes, melancholic drinkers, mothers and children found its fullest expression in his large-scale

Evocation (The Burial of Casagemas), Musée d’art moderne, Paris.

This ‘secular altarpiece’ was a valediction to Picasso’s dead friend and shows Casagemas ascending to heaven on a white stallion, surrounded by naked prostitutes, playful children, mourners and a madonna and child. This radical and highly unusual painting challenged the conventions of religious art. It will form the centrepiece of this exhibition and demonstrates the scale of Picasso’s aspirations, developed in 1901, to reinvent the language and traditions of painting. His ambition and confidence is further expressed in one of his most powerful and famous self-portraits in which he appears lit up against a dark background with a bold inscription proclaiming

Yo - Picasso (or I - Picasso), Private collection.