The Städel Museum

2/13–5/26/2019

Titian (c. 1488/90–1576), Madonna and Child, St Catherine and a Shepherd (the “Madonna of the Rabbit”), c. 1530. Oil on canvas, 71 x 87 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures ©bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Michèle Bellot. |

The Städel Museum is devoting a major special exhibition to one of the most momentous chapters in the history of European art: Venetian painting of the Renaissance. Entitled “Titian and the Renaissance in Venice”, the show unites more than a hundred masterpieces – In the early sixteenth century, artists of the “City of Water” developed an independent strain of the Renaissance relying on purely painterly means and the impact of light and colour. One of their most important exponents was Titian (ca. 1488/90–1576), who would hold the key position in the Venetian art scene all his life.

The Frankfurt show assembles more than twenty examples by Titian alone – and thus the most extensive selection of his works ever before on display in Germany. It also presents paintings and drawings by Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1435–1516), Jacopo Palma il Vecchio (1479/80–1528), Sebastiano del Piombo (ca. 1485–1547), Lorenzo Lotto (ca. 1480– 1556/57), Jacopo Tintoretto (ca. 1518/19–1594), Jacopo Bassano (ca. 1510–1592), Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) and others.

These works offer comprehensive insights into the artistic and thematic breadth of the Renaissance in Venice and elucidate why artists of later centuries looked back to the art of this time and place again and again for orientation. The exhibition introduces selected aspects of Venetian cinquecento painting in eight sections: for example its atmospherically charged landscape depictions, its ideal likenesses of beautiful women (the so-called “belle donne”), or the importance of colour.

The thematically oriented chapters together form a systematic panorama of the extensive material. Apart from the Venetian holdings in the Städel collection –

Titian (c. 1488/90–1576), Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1510. Oil on poplar, 20 x 17 cm. Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum © Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK.

including Titian’s Portrait of a Young Man (ca. 1510) – the show brings together superb loans from more than sixty national and international museums.

“This powerful theme – an art-historical classic – has recently come more strongly into focus in German museums. It gives us great pleasure to be able to present such a comprehensive, thematically structured panorama of Venetian painting of the Renaissance for the first time ever in Germany here in Frankfurt”, comments Städel director Philipp Demandt.

Titian’s contemporaries, for example Sebastiano del Piombo or Lorenzo Lotto, were soon spreading the innovations beyond the watery confines of Venice as well. The 1540s saw the emergence of a new generation of highly gifted artists, among them Jacopo Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese and Jacopo Bassano, who now likewise competed for commissions. It was Titian, however, who set the standards for his rivals and admirers alike. “Hardly any epoch of art history has known such continual reception. And within that context, Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese have been accorded the admiration otherwise reserved solely for Michelangelo and Raphael”, exhibition curator Bastian Eclercy emphasizes.

A Tour of the Exhibition

The exhibition begins by taking visitors on a representative tour of sixteenth-century Venice. In the giant woodcut

View of Venice (1498–1500; Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum) based on a design by Jacopo de’ Barbari and published by Anton Kolb, the unusual bird’s-eye perspective provides an astoundingly precise impression of the “Serenissima’s” unique topography.

The prominently placed, large-scale Rest on the Flight into Egypt (ca. 1572; Sarasota, FL, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art) by Paolo Veronese ushers visitors directly into the first section of the show, introducing a typically Venetian variation on the depiction of the Madonna, a dominant theme in Italy. In its painterly execution, this exotic altarpiece is considered a magnum opus of the Venetian Renaissance; it also marks both the end and the culmination of the development of a pictorial genre known as the “Sacra Conversazione” (“sacred conversation”). Over the course of the sixteenth century, the motif had been invested with ever greater vividness and interaction between the figures. And particularly in Venice, the traditional subject of the Virgin and Child was often expanded to include further protagonists.

From depictions of the Virgin Mary set in luxurious landscapes, the focus shifts to the genre of landscape painting proper – one of the great achievements of the Venetian Renaissance. Even if it is initially still linked with a figural narrative, landscape now takes centre stage as a signifier of mood. This chapter of the exhibition highlights both the lyrical natural sceneries by the early Titian and the dramatically charged ones by such artists as Veronese or Bassano. Over time, these works would come to serve as the foundation for the establishment of the landscape as a genre in its own right. Especially in their mythological compositions, the painters breathed new life into the idea of Arcadia romanticized by the poets of antiquity as an ideal environment.

At this juncture, the exhibition rooms open onto an architecture traversed by arcades. Artistic compositions inspired by poetry – already alluded to in the previous section – are featured here as an independent genre. Sixteenth-century Venetian painters of mythological scenes were no longer content with merely illustrating the literary material, but now laid claim to equal rights in the poetic license of invention. Among the examples representing this development are

Titian’s Boy with Dogs in a Landscape (ca. 1570–76; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen)

and Veronese’s Cupid with Two Dogs (ca. 1580; Munich, Alte Pinakothek), which bears a resemblance to the Titian work. Both paintings have continued to defy interpretation to this day.

The final section of this first part of the exhibition is like a return to reality – but only at first sight. That is because true-to-life likenesses of women were rare in Venice, whereas “ideal portraits” of beautiful ladies were quite common. Even if they are often classified as portrait paintings, the “belle donne” depicted in these works were presumably not real persons, but poetic ideals of feminine beauty.

Within the context of this exhibition, a new interpretation of

Sebastiano del Piombo’s fascinating Woman in Blue with Incense Burner (ca. 1510/11; Washington, National Gallery of Art) has led to its identification as an early example of this genre. It exhibits the typical features of the ideal of beauty prevailing in the period in question: a roundish face, voluptuous lips, an enigmatic gaze and dark blond hair.

An excursus in this section, based on the costume book De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo (1590; Of Ancient and Modern Dress of Diverse Parts of the World) by Cesare Vecellio, a cousin of Titian’s, is devoted to contemporary fashions in Venice and beyond.

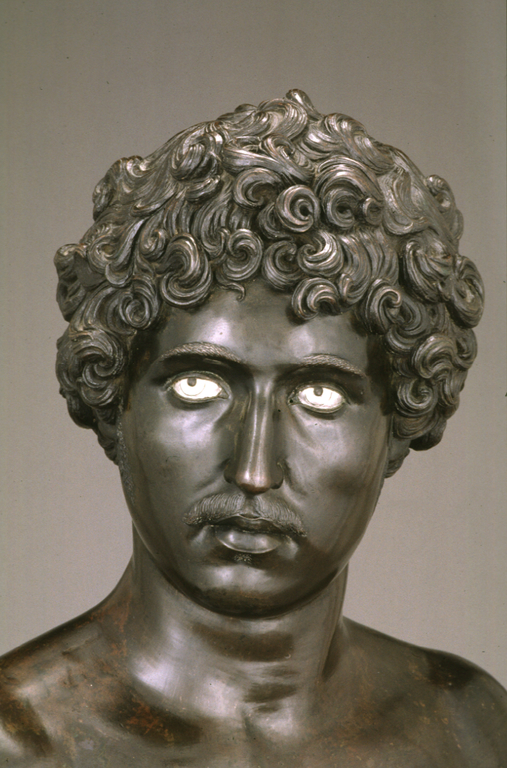

Now the tour continues on the first floor of the exhibition annex. Taking its starting point in the Frankfurt portrait of a young man from Titian’s early period, this chapter explores how the Venetian male portrait came to flourish in the cinquecento – and to exert a lasting influence on European portrait painting.

Characteristic examples here are the portraits of casually elegant young men in black, for example by Titian or Tintoretto, based on Baldassare Castiglione‘s Libro del cortegiano (1528; The Book of the Courtier). Yet expensively dressed wearers of ermine and portraits of the doges – the chief magistrates of the Republic of Venice – also contributed to shaping the image of the era.

At the centre of the room, visitors encounter three depictions of men in splendid armour. The special degree of mastery such paintings required of their makers is evident, for example, in Sebastiano del Piombo‘s Man in Armour (ca. 1511/12; Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

or Titian’s Portrait of Alfonso d’Avalos (ca. 1533; Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum). With their depictions of the gleaming metallic surfaces, the artists achieved a highly realistic impression of light.

Colour and effects – Unlike the painting of Florence and Rome, which was based more strongly on drawing, the Venetian Renaissance is distinguished above all by the art of colour, called “colorito”. The fact that Venice was a centre of the paint trade will surely have played a role in this phenomenon. The Venetian palette ranged from berry red to gloomy black, from chiaroscuro to brilliant polychromy. Whereas the Florentines favoured smooth, porcelain-like surfaces, the Venetians often left the brushstroke clearly visible as a testimony to the act of painting.

The second-to-last chapter of the show takes a look at the reception of Florentine art in the Venetian cinquecento. It was particularly the depiction of muscular male nudes as perfected by Michelangelo that impressed the Venetians in the art of Florence. Nude males such as Titian’s Frankfurt

Study of St Sebastian (ca. 1520) and his St John the Baptist (ca. 1530–33; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia), or

Tintoretto’s St Jerome (ca. 1571/72; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) bear witness to an indepth artistic study of the great Florentine master’s work and to a reciprocal influence.

The final section of the exhibition features a number of works representing the long history of its influence. Many of the most prominent artists have schooled themselves on this powerfully colourful painting and exported it – in the case of El Greco, for example, to Spain. The great French painters of the nineteenth century, for instance Théodore Géricault, were likewise among those to learn from Titian and Veronese.