Friday, November 30, 2012

Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich

This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum is hosting an extraordinary exhibition of rarely seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection.

Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München

The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. Dürer to de Kooning will occupy the Morgan’s two principal galleries. One gallery will contain more than sixty Italian, German, Dutch, and French drawings of the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries. Represented here will be such celebrated artists as Mantegna, Michelangelo, Pontormo, Raphael, Titian, Dürer, Rubens, Rembrandt, Bellange, and Friedrich. The second gallery features nearly forty late-nineteenth century and modern and contemporary works, including drawings by Vincent van Gogh, Emil Nolde, Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, David Hockney, Georg Baselitz, and Sigmar Polke.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938) Nude Girl in an Interior, ca. 1910 Inv. 1978:1 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München

ITALY

The Staaliche Graphische Sammlung is home to some 3,500 Italian drawings. The collection’s strength is sixteenth-century drawings by the most celebrated artists of the period: Leonardo da Vinci, Fra Bartolommeo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, Tintoretto, and Pontormo, all of whom are represented in the exhibition. Sheets by Benvenuto Cellini, Annibale Carracci, and Pietro da Cortona are also of particular note.

Highlights

Jacopo Pontormo (1494–1557) Two Standing Women, after 1530(?)

An outstanding example of Pontormo’s Mannerist style, this drawing is remarkable for its dynamism. It may be preparatory for one of the artist’s enigmatic depictions of the Visitation, envisioning the meeting of the pregnant Virgin Mary with her cousin Elizabeth. The abstraction of form, bold linearity, and tension between the figures contribute to the powerful appeal of this sheet.

Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506) Dancing Muse, ca. 1495

Recognized in his lifetime as the leading painter in Italy, Mantegna spent the latter part of his career working for the Gonzaga court in Mantua. This is likely the final study for one of the main figures in Mantegna’s Parnassus in the ducal palace of Mantua. It is especially notable for the artist’s masterful handling of the folds in the muse’s clothing. The figure’s face and hairstyle—both rendered in a sculptural style typical of the artist—appear in slightly different form in the finished painting.

Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669) The Age of Bronze: Design for a Mural in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence, ca. 1641

In celebration of his marriage, Ferdinand II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, commissioned Cortona to decorate Florence’s Palazzo Pitti with frescoes representing the Four Ages of Man, a theme drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This preparatory study for the Age of Bronze is notable for its lively energy, fluidity of the draftsmanship, and the broad, painterly pools of wash that signal its exploratory and inventive character.

GERMANY

Germany is the school most richly represented in Munich’s graphics collection, and many examples are included in the exhibition. An impressive variety of works is on display, including Hans Burgkmair the Elder’s Christ with the Crown of Thorns, the earliest red chalk drawing by any German artist; a fragment of a highly finished procession scene by Hans Holbein the Younger; window designs by Hans Schäufelin and Jörg Breu the Elder; fresco painter Melchior Steidl’s watercolor design for a monumental ceiling painting; landscapes by Joseph Anton Koch, Caspar David Friedrich, and Carl Rottmann; and a bold graphite-and-charcoal self-portrait by Wilhelm Leibl, a major figure in German art during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Highlights

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) Portrait of Kaspar Nützel, 1517

Dürer, the most important artist of the German Renaissance, returned to large-format portraiture in 1514 after an absence of more than ten years. This striking portrait of Kaspar Nützel, the artist’s friend and an important Nuremberg diplomat, has a storied provenance; once part of Paulus Praun’s celebrated collection of some ten thousand objects, the drawing was likely purchased by Crown Prince Ludwig, who later became King Ludwig I of Bavaria, in 1809.

Matthias Grünewald (ca. 1470/80–1528) Study of a Woman with Her Head Raised in Prayer

Few drawings by Grünewald survive, but those that do exhibit the haunting quality associated with his work that impressed twentieth-century artists as diverse as Otto Dix and Francis Bacon. This study and another on the reverse of the same sheet have been connected with the figures of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene on the crucifixion panel of the artist’s Isenheim Altarpiece.

THE NETHERLANDS

Of the Graphische Sammlung’s approximately 1,700 works by artists from the northern and southern Netherlands, fourteen of the finest were selected for the exhibition. Dutch drawings on view include important examples from sixteenth-century artists Hendrick Goltzius, Jacques de Gheyn, and Jan Harmensz Muller; and seventeenth-century drawings by Rembrandt, Ferdinand Bol, and Aelbert Cuyp. Outstanding seventeenth-century Flemish works by Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens are also on display.

Highlights

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) Saskia Lying in Bed, a Woman Sitting at Her Feet, ca. 1638

The exhibition includes three works from Munich’s collection of drawings by Rembrandt. The bedridden woman in this study, the most personal by the artist that is on view in the show, is most likely his wife Saskia, who was often ill or sapped of energy by her four pregnancies. Saskia’s precisely observed likeness, rendered by a fine pen, is juxtaposed to that of her maid in the foreground, whose figure was added in a rather cursory fashion with broad strokes of the brush. The contrast between these two drawing techniques sharpens the focus of the composition on Saskia’s pensive face.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) Study for the Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma, 1603

Rubens was just beginning his career when he completed this study for a larger-than-life equestrian portrait of the Duke of Lerma, commander-in-chief of the Spanish cavalry. The artist invested significant time and effort in perfecting the details of this, his largest known drawing, which is vividly worked with pen and brush. The resulting dynamic new approach to equestrian portraits would soon inspire imitations by the artist’s many followers.

FRANCE

Dürer to de Kooning features five examples from Munich’s select but impressive group of French drawings. On view is a stylistically diverse group of drawings by Antoine Caron, Jacques Bellange, Simon Vouet, and Laurent de la Hyre.

Highlights

Simon Vouet (1590–1649) Man Bending Over in Three-Quarter View, Two Heads with Turbans, ca. 1636

This luminous drawing likely served as preparation for one of Vouet’s most ambitious and lauded fresco commissions. Depicting the Adoration of the Magi, the frescoes adorned the chapel of the Hôtel Séguier, the private residence of Pierre Séguier, chancellor of France under Louis XIII and a preeminent patron of the arts. The chapel, now destroyed, was described by the eighteenth-century collector Dézallier d’Argenville as meriting “the attention of connoisseurs [because of] the beauty of his paintings and…the clarity of its gilding as fresh as if they were newly painted.”

Jacques Bellange (before 1575–1616) Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1610

Bellange is best known as a printmaker, although a small group of elegant Mannerist drawings reveal his talents as a draftsman. He used quick long lines in this first conceptual sketch for his largest etching, Adoration of the Magi. This work is remarkable for its bold approach to the composition and its exceptionally free handling, which exhibits a powerful use of line comparable to that later used in the etching.

MODERN

The Graphische Sammlung has become a top-ranking museum for modern European and American drawings and its holdings in this field now number some 7,000 sheets. Dürer to de Kooning includes twenty-six outstanding works by Vincent van Gogh, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Pablo Picasso, Max Beckmann, Sigmar Polke, Georg Baselitz, Jean Dubuffet, and David Hockney, among many others.

Highlights

Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) Standing Man, ca. 1951

The mask-like face of the figure in this study became one of the hallmarks of de Kooning’s Woman series, which laid the groundwork for a style—essentially a synthesis of abstraction and figuration—that revolutionized abstract art. The stylized ribs of the figure in this drawing were to reappear later in the artist’s crucifixion scenes of the early 1950s.

A. R. Penck (Ralf Winkler) (b. 1939) I and the Cosmos (Figure with Starry Sky), 1968

Penck was born in what became the German Democratic Republic, and remained behind the Iron Curtain until 1980. In order to elude the authorities and exhibit internationally, the largely self-taught artist—who was born Ralf Winkler—took on various aliases, the first and most lasting being A. R. Penck. In this striking sheet, a dramatically simplified solitary figure, identified in the title as the artist himself, faces a starry sky. The combination of red and black holds political connotations for its associations with anarchism and socialism.

ABOUT THE STAALICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG

The Staaliche Graphische Sammlung houses roughly 400,000 works covering the entire spectrum of drawing. Although the origins of the collection likely date to the sixteenth century, its documented history begins with Elector Carl Theodor (1724–1799) of the Palatinate who commissioned the creation of a kabinett of copperplate engravings and drawings for his palace at Mannheim in 1758. This collection, enlarged over time through continual acquisition, was moved to Munich in 1794–5 in order to safeguard it from approaching French revolutionary forces, forming the basis of the Staaliche Graphische Sammlung. The collection opened to the public in 1823 and became an independent museum in 1874.

ARTISTS ON VIEW

Egid Quirin Asam

Hans Baldung Grien

Federico Barocci

Fra Bartolommeo

Georg Baselitz

Johann Wolfgang

Baumgartner

Max Beckmann

Jacques Bellange

Johann Georg Bergmüller

Ferdinand Bol

Jörg the Elder Breu

Hans the Elder Burgkmair

Peter Candid

Antoine Caron

Annibale Carracci

Benvenuto Cellini

Giorgio de Chirico

Lovis Corinth

Pietro da Cortona

Aelbert Cuyp

Leonardo da Vinci

Johann Georg von Dillis

Jean Dubuffet

Albrecht Dürer

Adam Elsheimer

Caspar David Friedrich

Alessandro Galli-Bibiena

Jacques (Jacob) de Gheyn

Domenico Ghirlandaio

Vincent van Gogh

Hendrick Goltzius

George Grosz

Matthias Grünewald

Erich Heckel

Michael Heizer

David Hockney

Hans Holbein the Younger

Wolf Huber

Jacob Jordaens

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Wilhelm von Kobell

Joseph Anton Koch

Käthe Kollwitz

Willem de Kooning

Hans Süss von Kulmbach

Laurent de La Hyre

Wilhelm Leibl

Max Liebermann

Andrea Mantegna

Franz Marc

Hans von Marées

Jacob Matham

Adolph von Menzel

Michelangelo

Jan Harmensz. Muller

Bruce Nauman

Emil Nolde

Barent van Orley

Lelio Orsi

Johann Friedrich Overbeck

Palermo

Jules Pascin

Crispijn de Passe the Elder

A. R. Penck

Luca Penni

Francis Picabia

Pablo Picasso

Sigmar Polke

Antonio del Pollaiuolo

Jacopo Pontormo

Raphael

Arnulf Rainer

Rembrandt

Larry Rivers

Carl Rottmann

Peter Paul Rubens

Hans Schäufelin

Rudolf Schlichter

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

Melchior Steidl

Jacopo Tintoretto

Titian

Trometta

Perino del Vaga

Paulus Willemsz. van Vianen

Simon Vouet

Marco Zoppoxx

More Images here and here

Thursday, November 29, 2012

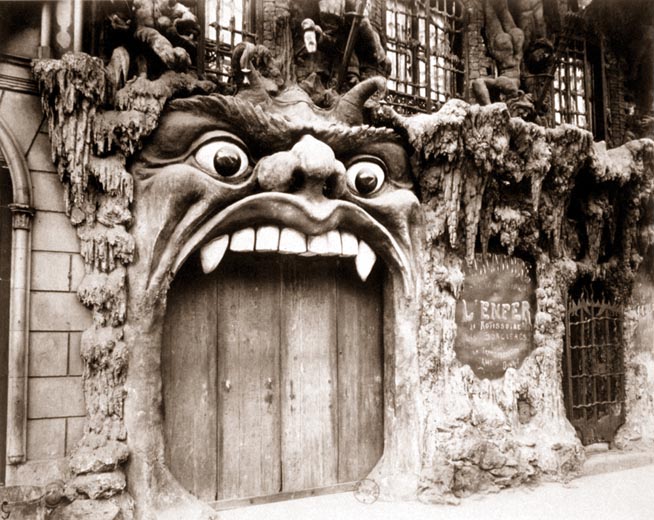

Paris in Transition: Photographs from the National Gallery of Art

Charles Nègre (1820 - 1880)

Tuileries Statue: Boreas Abducting Orithyia, 1859

albumen print from collodion negative

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1995.36.109

Paris in Transition: Photographs from the National Gallery of Art on view in the Washington, DC gallery from February 11 through May 6, 2007, presented 61 of the Gallery’s photographs revealing the transformation of the French capital city and the art of photography from the mid-19th to early 20th century. The exhibition included photographs by Eugène Atget, André Kertész, Brassaï, Alfred Stieglitz and others.

The Exhibition

Beginning with images of the city’s streets and architecture by photographic pioneers William Henry Fox Talbot, Gustave Le Gray, Auguste Mestral, Charles Nègre and others in the 1840s and 1850s, the exhibition highlighted the central role that Paris played both as subject matter and as a base for a burgeoning French school of photography.

Photographs include

Talbot’s Boulevards of Paris (1843),

Nègre's Market Scene at the Port of the Hôtel de Ville, Paris (1852)

and Edouard Denis Baldus' photographs of the Louvre.

Featuring photographs by Charles Marville, Louis-Émile Durandelle, Hippolyte-Auguste Collard and others, the exhibition also explores the urban transformations of Paris in the 1860s and 1870s under Napoleon III and his chief urban planner, Baron Haussmann. In the middle of the 19th century, Haussmann undertook a massive program to modernize the twisting alleys and narrow streets that characterized medieval Paris by creating spacious boulevards, wide sidewalks and large parks suitable for the leisure pursuit of an emerging bourgeoisie class, as well as furnishing the streets with modern conveniences such as streetlamps and information kiosks.

Marville, named Paris’s official photographer in 1862, was commissioned to document the streets and buildings of “Old Paris” slated for destruction.

In Rue Saint Jacques and Rue de la Bûcherie (both 1865-69), Marville recorded the city’s disappearing neighborhoods.

(See more images here)

But in Hôtel de la Marine (1872-76), he celebrated one of Haussmann’s achievements: the installation of one of the thousands of gas lamps that made Paris “the city of light.”

Other photographs convey the energy of modern Parisian life,

including Nadar’s Self-Portrait with Wife Ernestine in a Balloon Gondola (c. 1865)

and Collard’s photographs of construction projects near the city.

More images here

The exhibition highlighted Eugène Atget’s photographs of turn-of-the-century Paris. Training his camera on shop windows, sparsely populated streets and quiet parks, Atget presented Paris not as a geographical entity but as a series of individual spaces.

The Gallery’s collection of Atget’s photographs reveals his eye for the details of daily Parisian life, offering a contemplative and often romantic vision of the city that influenced later photographers. This section also presents photographs by other artists who were drawn to Paris during this time, including American photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

The exhibition closed with an examination of a new school of Parisian photography that emerged in the 1920s. Émigrés to Paris, André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Brassaï, Ilse Bing, Jaroslav Rössler and others were energized by the modernist culture that shaped Paris in the 1920s. Their work shows Paris as a pleasurable contradiction, offering by turns the comforts of nostalgia and the vertigo of modernity.

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Fantasy and Invention: Rosso Fiorentino and Sixteenth-Century Florentine Drawing

Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540)

Holy Family with the Young Saint John the

Baptist, ca. 1520

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Photo © The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

The emergence of Mannerism in Florentine Renaissance art as exemplified by the brilliant painter Rosso Fiorentino is the subject of a new exhibition at The Morgan Library & Museum, that opened on November 16, 2012. The show includes the artist’s extraordinary painting, Holy Family with the Young Saint John the Baptist, as well a selection of drawings, printed books, letters, and manuscripts by other Florentine masters. The Holy Family, on loan from the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, is one of only three paintings by Rosso in the United States. Fantasy and Invention: Rosso Fiorentino and Sixteenth-Century Florentine Drawing will remain on view at the Morgan through February 3, 2013.

Born Giovanni Battista di Jacopo di Guaspare in Florence, Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540) — so known because of his distinctive red hair — was one of the foremost exponents of the late Renaissance style known as Mannerism, or the maniera. Characterized by extreme artifice, effortless grace, and refinement, and given to displays of inventive fantasy, spatial ambiguity, and strange beauty, this style developed about 1520 simultaneously in Rome (in the circle of Raphael) and in Florence (in the work of artists associated with Andrea del Sarto). Using the Holy Family as a starting point, Fantasy and Invention traces the Florentine iteration of Mannerism through some twenty drawings from the Morgan’s collection; five autograph documents and letters from leading artists of the day, including Michelangelo; two printed books; and a rare drawing by Rosso, on loan from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Together, these works speak to the fundamental role of disegno—the Italian word for drawing that carries broader, theoretical connotations of artistic skill and invention—in the formulation of Mannerism.

The exhibition begins with the style’s antecedents in the High Renaissance as seen in major examples by Fra Bartolommeo and Andrea del Sarto. It then moves on to Mannerism’s early stirrings in the art of Rosso and Jacopo Pontormo and its elaboration by their younger contemporaries Francesco Salviati and Giorgio Vasari. Finally, Mannerism’s more formal, frozen codification later in the century is explored through the work of Agnolo Bronzino, Giovanni Battista Naldini, Alessandro Allori and others, many of whom were employed by the Medici rulers of Florence. “Fantasy and Invention offers museum-goers a sharply focused look at the development of Florentine Mannerism,” said William M.Griswold, director of The Morgan Library & Museum.

“With Rosso’s brilliant Holy Family as its centerpiece, supplemented by a carefully chosen selection of drawings and related material, the exhibition explores how the artist and his contemporaries approached the discipline of drawing, creating some of the most extraordinary and beautiful works of the Italian Renaissance.”

In his Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1568), Giorgio Vasari described Rosso as always showing “the invention of a poet in the grouping of his figures, besides being bold and well-grounded in draftsmanship, graceful in manner, sublime in the highest flights of imagination, and a master of beautiful composition.” The artist’s drawings, Vasari went on, “were held to be marvelous, for Rosso drew divinely well.”

A gifted painter, draftsman, print designer, and master of stucco, Rosso was also a notoriously quirky and difficult individual—he kept a pet monkey; had trouble with patrons; acknowledged his own arrogance; ran afoul of and was blacklisted by the powerful cabal of artists in Rome who had worked with the recently deceased and revered Raphael; and may have committed suicide by poison. Something of that personality seems to have left an imprint in the disturbing undercurrents of his style, resulting in highly original, emotionally expressive, and at times bizarre works of art—including one altarpiece that the patron judged so unsettling upon first seeing it that he fled the room in horror.

Affluent bankers, merchants, and patricians in Renaissance Florence frequently commissioned paintings of the Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist (the city’s patron saint) to hang in their palaces. For his early, unfinished Holy Family, painted for an unknown patron, Rosso cast the subject in his distinctive Mannerist style. The figures of Mary, Joseph, Jesus, and John the Baptist are confined within a tight, claustrophobic space, yet they lack any psychological interaction, each gazing in a different direction. The young John the Baptist wears a grapevine crown, an attribute of the ancient god Bacchus and a uniquely Florentine iconographic convention that fused pagan and Christian imagery. The strangely submissive figure of Saint Joseph at left of the ensemble adds to the mystery and emotional complexity of the painting—both defining features of Rosso’s work.

Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540) Bust of a Woman with an Elaborate Coiffure, 1530s

Black chalk, pen and brown ink; brown wash in background added by a later hand

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY,

U.S.A.

Michelangelo, Raphael, and ancient sculpture were the canonic models from which sixteenth-century artists drew inspiration. Rosso’s depiction of a woman with curling braids and a fanciful headdress harks back to similar female heads in Michelangelo’s frescoes and sculptures. Elaborate, finished drawings such as this were not preparatory studies for paintings, but rather stand-alone creations intended to display an artist’s creative prowess and powers of invention.

Fra Bartolommeo (1472–1517)

View of the Ospizio della Madonna del Lecceto from the West, ca. 1504–1508

Pen and brown ink

The Morgan Library & Museum

Purchased as the Gift of the Fellows

Fra Bartolommeo was one of the first Italian artists to create pure landscape drawings directly observed from nature. Not all the sites he depicted can be identified, but this example shows a convent in the Florentine countryside belonging to the Dominicans, the monastic order to which the artist professed his vows in 1500. The edifice seen here was completed around 1504, but whether the artist was drawing for pleasure or to create a visual record of Dominican real estate holdings cannot be determined.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

Studies of David and Goliath, 1550s

Black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum

In the mid-sixteenth century in literary and cultural circles in Florence, a debate known as the paragone (“comparison”) was waged over the relative merits of painting versus sculpture, the practitioners of each discipline arguing for the superiority of their chosen pursuit. Michelangelo advocated for sculpture, but his follower Daniele da Volterra used these small yet powerful drawings of David beheading Goliath for a painting of the same subject, thereby championing the opposing side of this theoretical disputation. The poet and historian Benedetto Varchi published the written responses of some artists—among them Michelangelo and Bronzino—to the paragone question in a volume also on view in the exhibition.

Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530)

Young Man with a Basket and a Sack on his Head, 1524

Black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum

The preeminent painter in Florence in the 1510s and 1520s, Andrea del Sarto oversaw a productive and industrious workshop whose ranks included Rosso, Pontormo, Vasari, and Salviati. This is a study for a figure gracefully mounting the stairs in a fresco of the Visitation in the Chiostro dello Scalzo—one of the most important undertakings of Sarto’s career, and one of the major artistic campaigns of the Florentine High Renaissance.

Jacopo Pontormo (1494–1556)

Male Nudes, ca. 1520

Red Chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum

See this image here

Like Rosso, Pontormo worked in the studio of Andrea del Sarto in the 1510s, and by the end of the decade he had become one of the leading proponents of Florentine Mannerism. The artist frequently favored red chalk when creating the vacant-eyed, elongated, and muscular but weightless figures that characterize his style. This striking, vaguely mysterious study of three nudes may have been executed in connection with a fresco that Pontormo painted in the Medici Villa of Poggio a Caiano outside Florence around 1521.

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1573)

Rearing Horse, ca 1546–48

Black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum

See this image here

The horse in this drawing—previously attributed to the sixteenth-century Florentine painter Alessandro Allori but recently recognized as the work of his teacher and adoptive father, Agnolo Bronzino—derives from one of the most influential sculptures of classical antiquity, the monumental Dioscuri, or Horse Tamers, on the Quirinal Hill, Rome. Bronzino must have made this study, which constitutes a highly important addition to the artist’s small oeuvre, during a trip to Rome in the later 1540s. He subsequently used it as a model for the horse that appears in a tapestry he designed for Cosimo I de’ Medici, Duke of Florence.

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572)

Autograph Letter to Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici,

April 15, 1564

The Morgan Library & Museum

Fantasy and Invention includes several letters and autograph documents written by some of the leading artists of the period on matters of artistic creation and production. Agnolo Bronzino sent this letter in his elegant script to his patron, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, thanking him for his salary. At the time, Bronzino was at work in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence and the church of S. Stefano in Pisa—both Medici commissions.

Francesco Salviati (1510–1563)

Study of a Bearded Man, 1540s

Black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum

A prolific and inventive draftsman, the ill-tempered Francesco Salviati divided his career between Florence and Rome where he worked for some of the most powerful patrons in both cities, among them the Medici and the Farnese. This striking work has long been thought to be an artistic invention—an example of a “type” that appears in the artist’s frescoes and other narrative compositions for which he would have used such a study as a model. However, the rather specific and descriptive physiognomy suggests that it may be a portrait, or at least based on the features of an actual sitter.

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574)

Design for a Ceiling in the Palazzo Vecchio,

Florence, ca. 1558–62

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum

Best known as the author of the The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (a copy of which is on view in the exhibition) Giorgio Vasari was also a painter and architect retained as court artist by Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici. He oversaw a large workshop and was engaged in the extensive decoration and refurbishment of the vast Palazzo Vecchio, the medieval town hall of Florence that was converted into a palace by Duke Cosimo. This carefully rendered and elaborate design—one of Vasari’s most celebrated drawings—is a study for a ceiling illustrating scenes from the life of Lorenzo de’ Medici, the de facto head of the Florentine government in the late fifteenth century. Lorenzo appears in the design’s center compartment, receiving gifts from the ambassadors of Naples, Milan, and Constantinople.

Naldini Colosseum in Rome, 1600

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Gabriel Orozco

The Museum of Modern Art presented the first major museum retrospective of the artist Gabriel Orozco (Mexican, b. 1962), who since the early 1990s has forged a career marked by continuing innovation and has become one of the leading artists of his generation. On view from December 13, 2009, through March 1, 2010, this midcareer retrospective examined two decades of Orozco’s career in an exhibition of some 80 works, revealing how the artist roams freely and fluently among drawing, photography, sculpture, installation, and painting to create a heterogeneous body of objects that resists categorization. Works in the exhibition came from international public and private collections, including the collection of The Museum of Modern Art.

Gabriel Orozco was organized by Ann Temkin, The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art, with Paulina Pobocha, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art.

Mobile Matrix (2006), a monumental sculpture composed of a reassembled gray-whale skeleton, was installed on the second floor in the Museum’s Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium. Orozco was commissioned to make the sculpture by Mexico’s National Council for Culture and the Arts for its permanent home in the Biblioteca Vasconcelos in Mexico City. Its inclusion in this exhibition marked the first time it had been seen outside of that library. After excavating the bones from the Isla Arena in Baja California Sur, Orozco and a team of approximately 20 assistants used some 6,000 mechanical pencils to draw lines on the whale that relate to its structure. Dark solid circles were surrounded by numerous series of concentric rings that overlap and collide with each other.

Explains Ms. Temkin, "Orozco’s transformation of the concept of sculpture—via innumerable mediums and methods—makes him a central figure of his generation. Sixteen years after his debut in MoMA’s Projects series, this exhibition explores both the consistency and the surprising evolution of his artistic approach."

Orozco was born in 1962 in Jalapa, in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, to Cristina Félix Romandía, a student of classical piano, and Mario Orozco Rivera, a mural painter and art professor at the Universidad Veracruzana. In 1981, Orozco enrolled at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (ENAP), a division of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), from which he graduated in 1984. In 1986, to broaden his knowledge of contemporary art practice, Orozco left Mexico City for Madrid. There he enrolled in courses at the Círculo de Bellas Artes and, using Madrid as a base, traveled throughout Europe; but by 1987, he returned to Mexico City. He formed a workshop with other artists—Damián Ortega, Gabriel Kuri, Abraham Cruzvillegas, and Dr. Lakra (Jerónimo López Ramírez)—and worked with this group for the next five years. Orozco spent the 1990s traveling to cities throughout the world, and many of his works were emblematic of the locations where they were made.

Bringing together objects originally created for autonomous settings and contexts, Orozco and Ms. Temkin have conceived this exhibition as a new landscape. Rather than offering a chronological or linear account of Orozco’s body of work, this exhibition celebrates the experimentation that lies at the heart of his practice. Orozco’s works were variously cerebral and spontaneous, convivial and hushed, the result of painstaking planning and fortunate accident.

The exhibition highlighted the diversity of Orozco’s materials and the variety of his methods while presenting an oeuvre that is unique in its formal power and intellectual rigor. Art and life combine in Orozco’s work.

Shown for the first time outside Mexico, a new work titled Eyes Under Elephant Foot (2009) is made of a section of a Beaucarnea tree trunk into which glass eyes have been set.

To create My Hands Are My Heart (1991), the artist squeezed a ball of clay between his two hands, forming a heart-shaped object that reveals the process of its making.

Rather than using a fine-art material, Orozco used clay made in a brick factory in Mexico. Like many of his early works, this object proceeds from a modesty of materials and simplicity of gesture, reducing the act of sculptural creation to its bare but potent essentials.

Nearby were two photographs showing the artist with My Hands were My Heart, exemplifying the close relationship that exists between photography and sculpture in Orozco’s work.

Among the works recreated here, only one was presented in a way that echoes its original installation:

Yogurt Caps (1994), which was first shown in Orozco’s debut exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York in 1994. Four blue-rimmed Dannon yogurt lids affixed to four otherwise empty walls punctuate the visual field so minimally as to be barely perceptible; by demarcating the perimeter of the gallery, Orozco’s intervention throws the emptiness of the room into focus.

For many of his sculptures from the 1990s, Orozco altered ready-made objects, such as an elevator, a car, or a bicycle. Without concealing the original object’s function or transforming its principal identity, he instead heightened its defining characteristics.

La DS (1993) is a streamlined version of the already sleek Citroën DS, made in Paris, where the cars were manufactured. Orozco cut a 1960s model in thirds lengthwise, removed about two feet of width from the center, and reassembled the two remaining sections to create a version of the original that exaggerates its aerodynamic design. Photography has been an essential component of Orozco’s practice throughout his career. There were images of objects he manipulated into sometimes poetic or humorous assemblages, and straightforward pictures of ready-made sculptural situations just as he found them.

Until You Find Another Yellow Schwalbe (1995), comprising 40 color prints, is Orozco’s lighthearted diary of his travels around Berlin. While riding his own yellow Schwalbe scooter—a popular motorbike produced in East Germany during the 1960s—he searched for other yellow Schwalbe scooters. Orozco parked his scooter next to nearly identical ones as he found them, and photographed them, eventually forming the series of 40 prints. By photographing these East German relics that punctuate the landscape of a unified Berlin, Orozco invokes Germany’s divided past.

In 2004, Orozco began to paint circles first on canvas and then on wood. Using a computer and drafting software, Orozco created a design template for a large series of paintings collectively titled Samurai Tree Invariants (2004, ongoing). Every panel in the series features four colors (gold, white, red, and blue) distributed across the canvas based on the movement of a knight in a game of chess.

Alongside the Invariants, Orozco has also produced a body of paintings, such as Kytes Tree (2005), whose compositional structures were unique to each work. Also on view were works like Fertile Structure (2008), made with graphite on a plaster-primed wood support. Melding painting and drawing, this recent work acknowledges the origins of Orozco’s painterly enterprise while suggesting the possibility of endless variation. The provisional objects of Orozco’s Working Tables, 2000–2005 illustrate the artist’s hand and mind in action, and provide an intimate look at his working process. The tables display prototypes for finished works, the beginnings of projects never realized, and found objects the artist kept for one reason or another—all things on their way to becoming sculpture. Several of the objects included in Working Tables, 2000–2005 relate directly to the finished sculptures, such as Floating Sinking Shell 2 (2004) and Double Tail (2002).

The exhibition traveled to three other museums after MoMA: Kunstmuseum Basel (April 18 to August 10, 2010); Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (September 15, 2010, to January 3, 2011); and the Tate Modern, London (January 19 to April 25, 2011). Each exhibition was a uniquely designed collaboration between the artist and the institution where it is presented.

RELATED EXHIBITION: Gabriel Orozco: Samurai Tree Invariants December 9, 2009–March 1, 2010 The Paul J. Sachs Prints and Illustrated Books Galleries, second floor On the occasion of the exhibition Gabriel Orozco, MoMA’s Department of Prints and Illustrated Books presented the artist’s Samurai Tree Invariants (2006), comprising a digital-print installation and computer animation, acquired for the Museum’s collection in 2008. Of the 672 prints in the series, 460 were on view in this exhibition. Limiting himself to the circle’s simple form and only four colors, Orozco multiplied, reduced, and shifted these elements according to a pre-determined system to create hundreds of sequential compositions on screen and paper. The resulting installation is an immersive space that combines digital precision with organic mutability, to mesmerizing effect. Orozco’s Samurai Tree Invariants represents an expanded concept of printmaking that embraces digital technology and encompasses installation art. The exhibition was organized by Gretchen L. Wagner, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, The Museum of Modern Art.

PUBLICATION:

The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue titled Gabriel Orozco, edited by Ann Temkin, The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art. It was designed by Pure+Applied in collaboration with Orozco. Critical essays by Ann Temkin; Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, The Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Modern Art, Harvard University; and Briony Fer, Professor of Art History at University College, London, provide new approaches to grounding Orozco’s work in the larger landscape of contemporary art. They were complemented by a richly illustrated chronology by Paulina Pobocha, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art, and Anne Byrd, an art historian and writer based in Brooklyn, New York, which combines biographical information with focused discussions of selected objects. These texts pay particular attention to Orozco’s material practice and introduce the artist’s own reflections on the work he has made. Hardcover: 256 pages; 500 color illustrations.

The exhibition website, www.moma.org/gabrielorozco, features approximately 90 works, along with roughly 60 pages from the artist’s notebooks. Navigation will allow visitors to explore Orozco’s work both chronologically and associatively. Audio and texts explain the significance of certain works. Video of the installation will also be featured. The site was designed by Shannon Darrough, Senior Media Developer, Department of Digital Media, The Museum of Modern Art, and developed by Sastry Appajosyula, RenderMonkey Design.

VIDEO: Clips of the exhibition will be posted to MoMA’s YouTube Channel and on MoMA.org. Please visit: YouTube: www.youtube.com/MoMAvideos MoMA.org Exhibition page: www.moma.org/gabrielorozco MoMA.org Multimedia page: www.moma.org/multimedia

TRAVEL: The exhibition traveled to the Kunstmuseum Basel, where it was on view from April 18 to August 10, 2010; the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, where it was on view from September 15, 2010, to January 3, 2011; and the Tate Modern, where it was on view from January 19 to April 25, 2011.

Monday, November 26, 2012

Pieter Claesz: Master of Haarlem Still Life

Pieter Claesz

Tabletop Still Life with Mince Pie and Basket of Grapes, 1625

oil on panel,

Private collection

Pieter Claesz: Master of Haarlem Still Life is the first international exhibition dedicated to the work of one of the most important 17th-century Dutch still-life painters. The exhibition was on view at the National Gallery of Art—the only U.S. venue— from September 18 through December 31, 2005.

Pieter Claesz featured 28 still lifes by Claesz (1596/1597–1660) from all phases of his career. It included more than 20 works by his predecessors and contemporaries, as well as glass, pewter, and silver objects of the sort found in Claesz’s still-life paintings. The works on view are drawn from museums and private collections in Europe and the United States, and together they provide a magnificent overview of this master’s work, who created visual feasts that delight the eye and whet the appetite.

The exhibition was presented earlier with variations at the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem (November 27, 2004, through April 4, 2005), and at the Kunsthaus Zürich (April 22 through August 22, 2005). The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, and the Kunsthaus Zürich.

The Exhibition

Pieter Claesz: Master of Haarlem Still Life was arranged chronologically and stylistically in the Gallery’s West Building Dutch Galleries and Cabinet Galleries.

Introduction

The earliest paintings by Claesz are carefully composed still lifes depicting food, tableware, and smoking and drinking utensils. While most of Claesz’s still-life paintings are modest in size, later in his career he also painted large banquet scenes brimming with sensuous foods and elegant tableware, such as

Still Life with Peacock Pie (1627). The Dutch made magnificent game pies for festive occasions, decorating the exterior of peacock, turkey, and pigeon pies with feathers and flourishes. Later in his career, Claesz collaborated on a number of still-life paintings with his Haarlem contemporary Roelof Koets, with whom he painted the large-scale banquet piece Still Life with Large Roemer and Fruit (1644). Claesz painted the left side of the composition while Koets executed the grapes and apples at the right. Also present in the first room of the exhibition were works by Claesz’s predecessors and contemporaries Osias Beert the Elder, Floris van Dijck, Willem Claesz Heda, and Gerret Willemsz Heda.

Pictorial Innovations and Vanitas Imagery

Tabletop Still Life with Mince Pie and Basket of Grapes (1625) (above) demonstrates a number of Claesz’s pictorial innovations. The vantage point is lowered, the perception of spatial depth increased, and the composition more unified in comparision to the previous generation’s work. Around 1625 Claesz began to paint “vanitas” compositions as a reminder of the transitory nature of life.

In Vanitas Still Life (1625) the candle and watch allude to the passage of time, while the skull and cut flower evoke the inevitability of death. Such images acted as a warning against attachment to material possessions and earthly pleasures.

Monochrome banquets

Claesz pioneered the development of the monochrome tabletop still life (the so-called “banketjes”)—quietly restrained works composed in sober tones yet imbued with an extraordinary sense of naturalism.

In Banquet Piece with Pie, Tazza, and Gilded Cup (1637), Claesz included incidental details, such as crumbs, nutshell remnants, and a disarrayed napkin, to suggest that a meal has been interrupted. In this work he carefully places a spoon on top of a partially eaten meat pie as an invitation to the viewer to participate in the feast. In the “banketjes,” Claesz relied on a monochrome palette to present the subtlest refinement of color and tone.

The actual cup of the Guild of St. Martin depicted in the monochromatic Still Life with the Covered Cup of the Haarlem Brewer's Guild (1641) will be on display alongside the painting.

Sumptuous Still Lifes: Unlike the simple repasts depicted in his breakfast pieces, Claesz’s later compositions are often quite elaborate, filled with a variety of foods, glasses, and serving platters dramatically strewn across the table, as seen in Sumptuous Still Life with Roast Capon and Oysters (1647).

Pieter Claesz (1596/1597–1660)

Pieter Claesz was born in Berchem, a village near Antwerp. Almost nothing is known of his early years, including the names of his parents or the identity of his teacher, though it is likely he studied in Antwerp. Around 1621 Claesz moved permanently to Haarlem, a major Dutch art center that was home to many distinguished artists, among them several still-life painters, who benefited from the patronage of the town’s wealthy citizenry. Claesz’s innovative ways soon gained recognition. Leading families of Haarlem acquired his paintings, displaying them prominently in their houses. Claesz was a prolific painter who signed most of his pictures with the monogram PC. Claesz’s son, Nicolaes Pietersz Berchem, became an important landscape artist in the mid-1600s.

Exhibition Curator, Related Activities, and Catalogue

The curator of the exhibition in Washington was Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., curator of northern baroque painting at the National Gallery of Art since 1984 and curator of such important Gallery exhibitions as Johannes Vermeer (1995–1996), Jan Steen: Painter and Storyteller (1996), Gerard ter Borch (2004), and Rembrandt's Late Religious Portraits (2005).

Pieter Claesz: Master of Haarlem Still Life by Pieter Biesboer, Martina Brunner-Bulst, Henry D. Gregory, and Christian Klemm is published by Waanders Publishers, Zwolle. The 176-page, hardcover catalogue includes 80 color illustrations and 20 black-and-white reproductions.

Still Life with Turkey Pie

Still Life with Oysters

More Images

James Ensor

The Museum of Modern Art(NYC) presented James Ensor—the first exhibition at an American institution to feature the full range of his media in over 30 years—from June 28 through September 21, 2009. James Ensor (Belgian, 1860–1949) was a major figure in the Belgian avant-garde of the late nineteenth century and an important precursor to the development of Expressionism in the early twentieth. In both respects, he has influenced generations of later artists.

Ensor’s daring, experiential work ranges from traditional subject matter such as still life, landscape, and religious symbolism to more singular visions, including fantastical scenes with masks, skeletons, and other startling figures. He made work in a wide range of styles and dimensions, from large-scale paintings and drawings to tiny prints of only a few inches. The exhibition elucidates Ensor’s contribution to modern art, including his innovative and allegorical use of light, his prominent use of satire, his deep interest in carnival and performance, and his own self-fashioning and use of masking, travesty, and role-playing.

Approximately 120 of Ensor’s paintings, drawings, and prints were included in the exhibition, most of which date from the artist’s creative peak, 1880 to the mid-1890s. The exhibition is organized chronologically, and within that chronology are thematic groupings such as Ensor’s self-portraiture, or his satirical works. A number of works, including the first two drawings from his monumental Aureoles series of 1885–86,

The Lively and Radiant: The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem

and The Rising: Christ Shown to the People, had never before been seen in the United States.

The first painting on view in the exhibition was The Scandalized Masks (1883), an example of the evocative paintings of masks in portraits and fictive dramas for which Ensor is best known.

Ensor lived in Ostend, Belgium—a fashionable resort known for its beaches, spas, and casino—from his birth in 1860 to his death in 1949. He left Ostend only for a brief period, from 1877 to 1880, to attend the Académie royale des beaux-arts, a prestigious training ground for young artists. Ensor was surrounded by masks throughout his life. He saw them for sale in his family’s souvenir shop in Ostend, and worn by revelers in the annual Carnival celebration. The bawdry puns and silly pratfalls of traveling vaudeville acts in Ostend, and even his grandmother’s eccentric penchant for dressing up in strange costumes, all nourished Ensor’s appreciation for farce and disguise.

Early works in the exhibition, such as The Lamp-Lighter (1880), were made soon after Ensor’s schooling in Brussels.

Ensor masterfully combined the genres of still life, portraiture, and interior scene in a painting considered among his best of the period, The Oyster Eater (1882). This life-size image shows his sister Mitche absorbed in a meal of oysters at a table decorated with flowers, dishes, and linens. Every element of the painting illustrates Ensor’s interest in the power and qualities of light. The Oyster Eater made its first public appearance at the 1886 exhibition of Les Vingt (Les XX), an avant-garde art society cofounded by Ensor in 1883 as an alternative to the official academic Salon. Ensor regularly exhibited in Les Vingt annuals, and the group would prove critically important for his artistic development.

Ensor’s overarching interest in light soon came to dominate his artistic vision, inspiring him to develop a drawing technique that would make objects seem suffused by light. Discovering that this formal innovation had expressive potential, he soon made light a subject in itself, an agent of symbolic intention, conveying ideas and evoking mood. He perfected his drafting techniques in Visions: The Aureoles of Christ, or The Sensibilities of Light, a series of six drawings from 1885–86. The series indicates a switch from Ensor’s depiction of reality-based subjects toward more imagined, fictionalized scenes. The most accomplished of these drawings, The Lively and Radiant: The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (1885), presents a biblical event in a contemporary, urban setting resembling Brussels, and is especially notable for its large dimensions. At nearly seven feet high, it is a scale that, at the time, was almost always reserved for painting.

A restless and incessant experimenter with a variety of mediums and techniques including collage and hand-printed etching, Ensor even revisited works completed years earlier, adding colors and images that often radically transformed the originals. For example, Ensor revisited his Self-Portrait with a Flowered Hat of 1883, adding a plumed hat and other elements that make the new image resemble a self-portrait by the Flemish Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens.

He also depicted himself in his works repeatedly, in keeping with his own sense of subversive play, while divulging the influence of theater and popular culture on his work.

In Self-Portrait with Masks (1899), he portrays himself as a young artist—in the same pose as

Self-Portrait with a Flowered Hat (1883/1888), finished 11 years before. His steady regard, outsize dimensions, and red hat set him apart from the masked crowd, to which he turns his back. Proclaiming his allegiance with masquerade and performance, Ensor opts for a public image that is overtly and completely contrived.

Ensor had a number of lifelong obsessions that were prominent subjects in his work—masks, light, himself, and death. Skulls or full-body skeletons appear in his works repeatedly and in a variety of ways. In Skeletons Trying to Warm Themselves (1889), a group of skulls draped in fabric absurdly and vainly seek heat from a dead stove. Ensor used the image of death to depict people he despised, such as the two skeleton-critics ripping apart a witty, metaphorical version of himself in Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring (1891). And death was even a theme of Ensor’s self-portraits, as with My Skeletonized Portrait (1889) and The Skeleton Painter (1895 or 1896). These two works were based on photographs: he transformed his pictured naturalistic countenance into skeleton versions of himself. Ensor’s use of photography as pictorial source material and his practice of collage were consistent with his experimental nature, as they are both techniques that placed Ensor ahead of his time.

A study room includes a wrap-around chronology on its walls that affords viewers the opportunity to learn more about the life of Ensor and his diverse range of interests. Beyond his career as an artist, he was involved in music, choreographed a ballet, and was an avid writer. This multitude of interests translates directly into the diversity of Ensor’s artistic oeuvre.

The exhibition concluded with satirical works focusing on contemporary political and social issues of Ensor’s time, which use grotesque exaggeration and base humor to make their point. Influenced by folk tradition, satirical journals, actualités, and burlesque theater, these pieces make Ensor’s radical individualism and political perspective patently clear. Examples are Doctrinaire Nourishment (1889), a scatological image of the king and other figures of Belgian authority excreting feces onto a group of citizens, and The Wise Judges (1891), a harsh criticism of the country’s judicial system. Ultimately, the exhibition presented Ensor as a socially engaged and self-critical artist involved with the issues of his times and with contemporary debates on the nature of modernism.

PUBLICATION:

The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue edited by Anna Swinborne. It includes essays by Anna Swinbourne; Susan M. Canning, Professor of Art History, College of New Rochelle, New York; Michel Draguet, Director, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels; Robert Hoozee, Director, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent; Herwig Todts, Curator, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp; Laurence Madeline, Curator, Musée d’Orsay, Paris; and Jane Panetta, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art. It was published by The Museum of Modern Art. Hardcover: 208 pages, 152 color illustrations.

WEBSITE:

The exhibition website, www.moma.org/jamesensor, features approximately 120 works, which visitors may zoom in on to explore details. Audio and texts explain the significance of certain works. An expanded chronology of Ensor’s life is included, as are excerpts from the essays in the exhibition catalogue. The site was designed and developed by Shannon Darrough, Senior Media Developer, Department of Digital Media, The Museum of Modern Art.

More Images:

The Baths of Ostend, 1890

The Dangerous Cooks

The Banquet of the Starved, 1915

MORE IMAGES:

Here

and here

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)