Wednesday, November 14, 2012

Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300–1350,

The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures, about 1315-20. Giotto di Bondone (Italian, about 1267–1337). Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Private Collection

In the first half of the fourteenth century, Florence was uniquely positioned as a flourishing center of artistic production, especially in the area of painting and manuscript illumination. Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300–1350, a major international loan exhibition on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum from November 13, 2012 through February 10, 2013, will present the most prominent Florentine artists of this era, and will feature the largest grouping of paintings by the Florentine master Giotto di Bondone ever exhibited in North America.

The exhibition will focus on those artists who worked as both panel painters and manuscript illuminators, examining these two media side by side and offering a fresh look at the distinctive artistic community that gave rise to the Italian Renaissance. Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum with the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), this major international loan exhibition will feature more than 90 works of art, including paintings, illuminated manuscripts, and stained glass and will present new findings about artists’ techniques and workshop practices based on conservation research and scientific analysis.

Artists featured in the exhibition include Giotto di Bondone (about 1267–1337), Taddeo Gaddi (about 1300–1366), Pacino di Bonaguida (active about 1303– about 1347), Bernardo Daddi (active about 1312–1348), the Master of the Dominican Effigies (active about 1325–1355), and the Master of the Codex of Saint George (active about 1315– about 1335), among others. In Los Angeles, the exhibition will include seven works by Giotto, the largest grouping of his paintings ever exhibited in North America.

The Ascension of Christ, about 1340. Pacino di Bonaguida (Italian (Florentine), active about 1303–about 1347). Tempera and gold on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 80a, verso

“By examining painting and manuscript illumination side-by-side, in concert with new scientific analysis, this exhibition will offer a fresh perspective on a pivotal moment in the history of art,” said Dr. Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “The revolution in the construction of pictorial space and the representation of emotion that Giotto pioneered changed forever the trajectory of European art. This exhibition brings that moment vividly to life, drawing on the latest analysis and art historical research, through a breathtaking selection of works from early Renaissance Florence. This is a landmark opportunity for Los Angeles audiences that should not be missed."

From 1300–1350, Florence was the focus of an extraordinary cultural flourishing that witnessed rapid civic and church growth, the production of new literary and humanist texts, and the rise of the merchant class. It was also home to the iconic literary figure Dante Alighieri (1265–1321). This dynamic climate generated great demand for artistic production, both in the elaborate decoration of sacred and secular buildings, and in the many luxury copies of manuscripts needed to feed the devotional and intellectual demands of the people of Florence.

Florence was also home to Giotto, who is regarded as one of history’s greatest painters, and even during his lifetime was celebrated by Dante and other cultural figures. He was sought after for commissions by wealthy patrons such as the Peruzzi family, important bankers in Florence.

On view in the exhibition, the Peruzzi Altarpiece, about 1309–1315, was commissioned for their private chapel in the church of Santa Croce. Here Giotto depicts five monumental figures, including Saints Francis, John the Evangelist, and John the Baptist with a new level of attention to natural detail, from realistic facial features to an awareness of the body beneath heavy garments to a profound dignity in posture and gaze.

Peruzzi Altarpiece, about 1309-1315. Giotto di Bondone (Italian, about 1267–1337). Tempera and gold leaf on panel. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, GL.60.17.7

Painters and illuminators such as Bernardo Daddi and Pacino di Bonaguida were inspired by Giotto’s new approaches—especially his depiction of the human form and narrative techniques—but quickly developed their own distinctive styles. Florentine artists provided an enormous output of objects at this time, ranging from devotional triptychs to books used for church ceremonies. These artists often collaborated on commissions or practiced their craft in a workshop setting.

“We are now able to present a richer, more nuanced picture of the beauty and creativity of the artistic production in fourteenth-century Florence than ever before,” explains Dr. Christine Sciacca, assistant curator of manuscripts at the Getty Museum, and the exhibition’s curator. “The phenomenon of the workshop formed the foundation of artistic production in Florence at this time and Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance will explore this and other issues through outstanding examples of paintings and illuminations from the likes of Giotto di Bondone and Pacino di Bonaguida.”

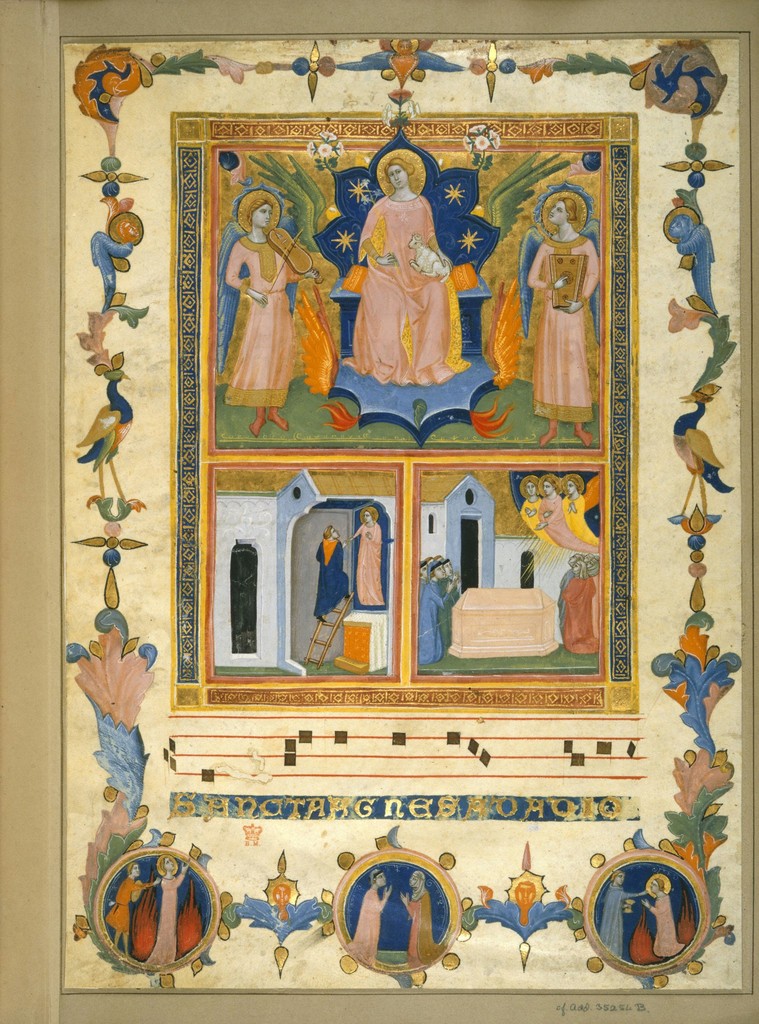

In addition to a large selection of paintings by Giotto, Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300–1350, will present the most important illuminated manuscript commission from the first half of the fourteenth century, the Laudario of Sant’Agnese. Illuminated by Pacino di Bonaguida and the Master of the Dominican Effigies, this beautifully executed and ambitiously designed illuminated manuscript was dismantled and dispersed sometime in the nineteenth century. The two dozen leaves that survive exhibit a great variety of imagery celebrating Christian feasts. This exhibition reunites nearly all of the surviving leaves for the first time.

Also featured in the exhibition are three illuminated copies of the Divine Comedy, Dante’s beloved literary masterpiece tracing the author’s journey from the depths of hell to the heights of heaven. Soon after Dante’s death, Pacino and the Master of the Dominican Effigies illuminated this text, visualizing the captivating events that the author described and feeding the demand for illustrated copies of what was quickly becoming a best-seller among Florentine citizens. The groundbreaking visual iconography developed to represent Dante’s narrative set the stage for the later artists who illuminated this popular text well into the fifteenth century.

Painting and Narrative

Building on the thirteenth-century traditions of depicting scenes from the lives of the saints in paintings (known as vita icons), artists of the early fourteenth century developed innovative ways of portraying elaborate, multi-episode religious narratives, especially those drawn from the life of Christ and the Christian saints. Florentine artists portrayed extended stories through a series of individual events shown in sequence,like frames in a movie or a graphic novel. This treatment allowed the viewer to contemplate each moment in turn and to meditate on its significance.

The Master of the Codex of Saint George, for example, is a painter and illuminator known for his beautifully rendered and evocative narrative scenes. Featured in the exhibition, four panels by the artist The Crucifixion, The Lamentation, The Risen Christ Appearing to Mary Magdelene, and The Coronation of the Virgin (all about 1328–1335), depict images from the end of Christ’s life. Displayed together for the first time since their separation (likely in the nineteenth century), these panels were originally hinged to form a portable devotional altarpiece.

Scientific and Technical Analysis

One section of the exhibition will describe the work and findings of a team of Getty conservators and conservation scientists who have examined a number of illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings from the period, including leaves from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, in order to gather information about artistic techniques common in early-fourteenth-century Florentine workshops. The appearance of many early panel paintings has changed over time due to environmental conditions and previous restorations, while manuscripts often maintain their original appearance. Thus, a direct comparison with illuminations provides important information about early painting and informs our understanding of the original splendor of these works.

The Chiarito Tabernacle, part of the Getty Museum’s permanent collection, is a panel painting that underwent digital color reconstruction for the exhibition: the blue background had darkened to almost black, the pink robes had faded, and in some yellow areas the pigment had fallen away. These pigments were identified using scientific analysis and their original appearance in the Tabernacle was calculated using similar areas from better-preserved works as references. The resulting partial digital color reconstruction will be shown in the exhibition, providing an informed visualization of how the painting may originally have appeared.

In the Context of Devotion

Although today these paintings and manuscripts are often viewed separately from each other in the context of museums, they originally functioned together in liturgical ceremonies, especially the mass. Throughout the Middle Ages, various types of paintings and manuscripts were created to aid Christians in their religious devotion and this production increased in the early fourteenth century with the rise of the mendicant (preaching) orders of the Franciscans and the Dominicans who sponsored much of the art produced in Florence in this period.

In Florentine churches, multi-paneled paintings graced the altars of chapels, large-scale crucifixes hung above altars, illuminated manuscripts provided sources for liturgical texts and hymns, small crosses were carried in procession in churches and through the streets, and stained glass windows provided luminous scenes on the walls of the church space. Individual worship outside the mass also took place in private family chapels and in the cells of monks and friars, and smaller panel paintings, such as diptychs and small triptychs, enhanced this devotion.

By bringing these works of art together in an exhibition setting, Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300–1350, evokes this original context and demonstrates the way that manuscript illumination, painting and other media were meant to work together in the lives of the faithful in fourteenth-century Florence.

The Nativity with the Annunciation to the Shepherds, about 1340. Master of the Dominican Effigies (Italian, active ca. 1325-ca. 1355). Tempera, gold leaf, and ink on parchment. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection, 1949-.5.87 194

The exhibition Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300–1350, is accompanied by a

color-illustrated volume of the same name, edited by Christine Sciacca and published by Getty Publications. Curated by Sciacca, with coordinating curator Sasha Suda, assistant curator of European art at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), in Toronto, Canada, the exhibition will be on view at the AGO from March 16, 2013 through June 16, 2013.

More Images From The Exhibition:

A Crowned Virgin Martyr, about 1340

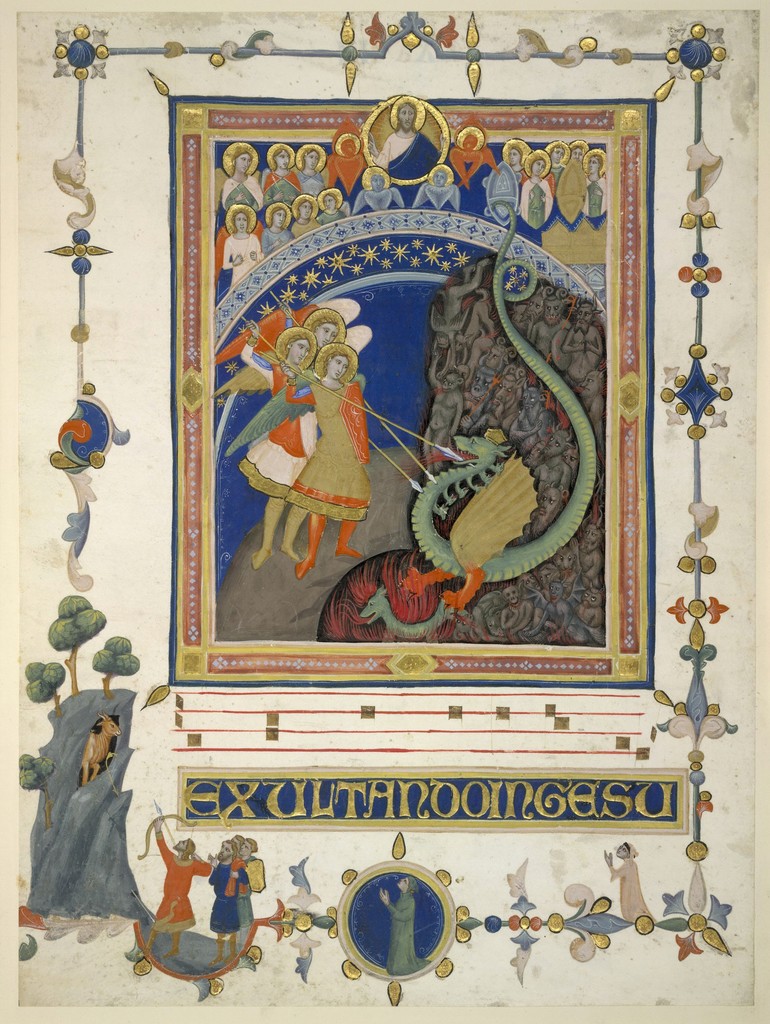

The Apparition of Saint Michael, about 1340

Saint Agnes Enthroned and Scenes from Her Legend, about 1340

The Virgin Mary with Saints Thomas Aquinas and Paul, about 1330