It is the 150th anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s birthday that offered the Albertina (Vienna) the occasion to pay tribute to the phenomenal draftsman. The Albertina is in possession of 170 of the artist’s most important drawings, among them sheets from all phases of his production. Gustav Klimt The Drawings March 14 – June 10, 2012 highlighted Klimt’s unique talent as a draftsman, whose manner of thinking and method of work are immediately evident in his numerous figure studies, monumental work drawings, and elaborately executed allegories. It is the first time that these unparalleled works are presented in the Albertina – the center of research for Klimt’s drawings – in a solo exhibition after fifty years.

Gustav Klimt the Draftsman

Gustav Klimt was such a brilliant draftsman that he occupies a unique position worldwide. The central subject of his more than 4,000 sheets is the human – particularly the female – figure. From 1900 on, he revolutionized the depiction of the nude: his sophisticated erotic studies blazed the trail for the Austrian Expressionists’ uninhibited depiction of the human being, particularly for Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka. But Klimt also pointed the way for younger colleagues with his figure studies allegorizing “The Sufferings of Weak Humanity.”

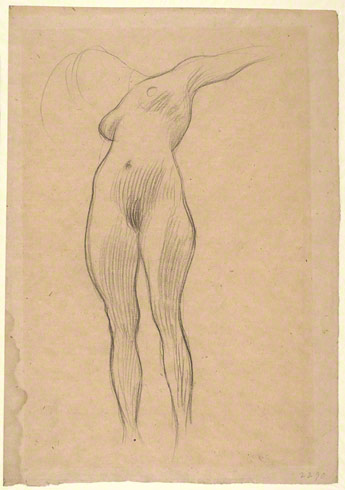

The practice of daily drawing after nude or clothed models remained crucial for Klimt throughout his life. The artist produced innumerable studies of women and men of all ages, as well as of children, in the context of his painted allegories of life. Untiringly exploring his figures’ poses and gestures, he fathomed the essence of specific emotional values and existential situations. As if in a trance, his figures, anchored in the picture plane, submit to an invisible order, whether in states of dream, meditation, or erotic ecstasy. It is the idea of a fateful bond between man and the cycle of life determined by Eros, love, birth, and death that provided the background for this kind of representation. The numerous studies for his portraits of women convey an air of majestic enrapture.

Klimt’s figures strike us as equally sensuous and transcendent. The artist’s endeavors are characterized by a subtle balancing act between the uninhibited stroke and formal discipline. His brilliant art of the line becomes manifest in every phase of his development – whether in the photographically realistic precision of the 1880s, in the flowing linearity of the period around 1900, in the metallic linear sharpness of the Golden Style, or in the nervous expressiveness of his late years. Though being related to his paintings, Klimt’s drawings constitute a world of its own and,because of the immediacy of their expression, offer deep insights into the artist’s working methods and intellectual universe.

The Klimt Collection of the Albertina

In the possession of 170 works by the artist, the Albertina holds one of the most comprehensive collections of Gustav Klimt’s high-carat drawings. The sheets exemplify all phases, techniques, and genres of representation in the artist’s production. Klimt frequently relied on black, red or white chalk, later on pencil, occasionally on pen and ink, or on watercolors. The range of his works’ functions spans from figure studies and illustrations for books to monumental preparatory sheets and meticulously detailed allegories. Besides studies of female and – less frequent – male heads, the exclusive genre of completely executed portrait drawings is excellently represented. Of particular interest are the series of studies connected to various paintings; they will be shown in the exhibition in their entirety for the first time.

The Albertina as a Center of Research for Gustav Klimt’s Drawings

The Albertina’s position as a center of research for Gustav Klimt’s drawings was established by the exhibition activities and studies of Alice Strobl, who was curator at the Albertina, before she became its Vice-Director. From the 1960s on, she documented and investigated all of Gustav Klimt’s drawings scattered across the world. Between 1980 and 1989, the Albertina published the four- volume catalogue raisonné of Gustav Klimt’s drawings that she wrote and which encompasses descriptions of nearly four thousand items. This work is still a milestone of Klimt scholarship. Beginning in 1975, the later Albertina curator Marian Bisanz-Prakken was of crucial assistance in dating the artist’s sheets. Since 1991, Marian Bisanz-Prakken has had sole responsibility for this cataloguing work; she will publish all new additions in a supplementary volume. Thanks to this continuity in the area of Klimt scholarship, the Albertina has for decades been the international authority on the assessment of Gustav Klimt’s drawings.

This is why the museum naturally felt the responsibility to devote a comprehensive exhibition to Klimt’s drawings on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of his birthday. The last show in the Albertina presenting exclusively drawings by Klimt was to be seen on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birthday in 1962. For the 50th anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s and Egon Schiele’s demise, the drawings of both artists were paid tribute to in an exhibition in 1968.

The Exhibition

Next to 30 outstanding loans from collections in Austria and abroad, 130 of Klimt’s 170 drawings in the possession of the Albertina were shown in the exhibition – among them works presented in Vienna for the first time such as

the life-size transfer sketch for

The Three Ages of Woman, the icon-like drawing of a standing couple, for which the artist used gold and which was made in the context of

The Kiss

and “Fulfillment,”

or the brush and ink drawing Fish Blood that has only recently turned up in a private collection.

The exhibition unfolds in four chapters that explore the main phases of the artist’s development. Though the comparison with the relevant paintings plays an important role, it is always the

autonomy of the drawing that the presentation emphasizes. Each sheet constitutes a world of its own and often goes far beyond the representation of the theme in the respective painting.

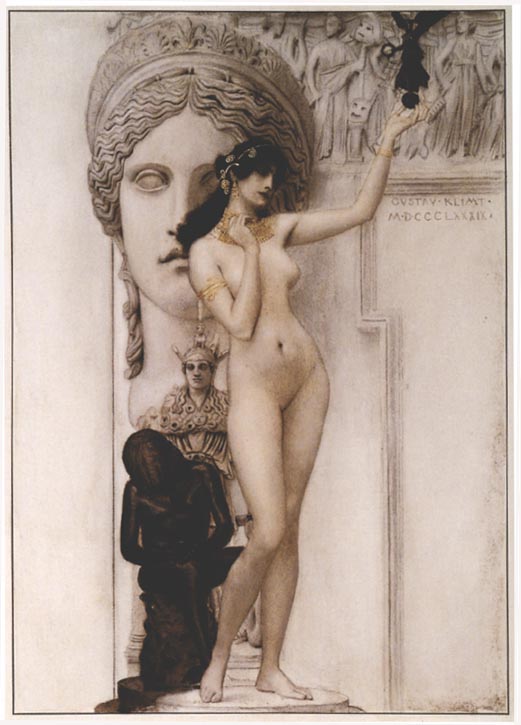

1. Historicism and Early Symbolism (1882–1892)

This chapter surveys the years from the last phase of Klimt’s studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule to the crisis year of 1892 in which he lost his younger brother Ernst, with whom he had closely collaborated, and his father. Highlights of this group are the head and figure studies for the Burgtheater paintings and the spectacular

Allegory of Sculpture, which already heralds the artist’s transition to Symbolism.

2. The Turn to Modernism and the Secession (1895–1903)

With his contribution to Allegorien, Neue Folge, Klimt professed his faith in Symbolism publically for the first time. In 1897, he was appointed president of the newly founded Secession. The works presented in this section include Klimt’s illustrations for Ver Sacrum, portraits of anonymous sitters, as well as numerous studies for his faculty paintings Philosophy,

Medicine,

and Jurisprudence and the Beethoven Frieze. His studies for portraits of women of Viennese society, a genre newly developed by the artist, constitute a group of its own.

3. The Golden Style (1903–1908)

Parallel to his work on his paintings in the Golden Style, Klimt’s creativity as a draftsman reached a culmination in these years. Around 1904, the artist switched from black chalk on wrapping paper to graphite pencil on Japan paper. In the context of his studies for Water Snakes I and

II he thematized the taboo topics lesbian love and autoeroticism for the first time. This chapter of the presentation highlights the studies for pregnant women in Hope I and II, The Three Ages of Woman, The Kiss, “Fulfillment” and “Expectation” in the Stoclet Frieze, Judith II (Salome), and the first version of Death and Life. A series of studies for various portrait paintings are shown next to various autonomous, painterly portrait drawings.

4. The Late Years (1910–1918)

From 1910 on, Klimt increasingly focused on erotic themes in his work as a draftsman. He not only made entire series of studies for his major works

The Virgin

and The Bride,

but also numerous autonomous drawings.

The studies for portraits of women, for which he received many commissions in those years, occupy an important place. Concentrating on specific types, Klimt also dedicated himself to half-length and head-and-shoulder portraits of anonymous female sitters.

The Cooperation with the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles

After the presentation in the Albertina, a large part of the works, complemented by a number of important loans, will be shown in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which will not only base its exhibition on the Albertina’s concept, but also use the English version of its catalogue. This will be the first exhibition dedicated to Gustav Klimt on the West Coast.

Biography Gustav Klimt

1862 Gustav Klimt is born on 14 July the son of the gold engraver Ernst Klimt in Baumgarten near Vienna.

1876–83 At the age of 14, Klimt is enrolled at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts; he is supposed to become a drawing teacher, like his younger brother. After two years, he switches to the decorative painting course; his most important teacher is Professor Ferdinand Laufberger.

1879 Together with Franz Matsch, the Klimt brothers establish and share a studio that operates successfully under the name of Künstler-Compagnie [The Company of Artists]. In 1882/3, they start their collaboration with the architects Ferdinand Hellmer and Hermann Helmer, who are engaged in the design of theatre buildings across the monarchy.

1886–88 The Künstler-Compagnie has sweeping success with the ceiling paintings in the right-hand grand staircase at the Vienna Burgtheater.

1890/1 The decoration of the staircase in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna turns out to be the Künstler-Compagnie’s last great triumph.

1892 After the death of his father and that of his brother Ernst, Klimt experiences a personal and creative crisis. He takes an increasing interest in Symbolism.

1894 Klimt and Matsch are commissioned to decorate the ceiling in the Great Hall of the University of Vienna with allegories depicting the arts and sciences. Klimt devotes himself to the disciplines of philosophy, medicine, and jurisprudence.

1897 Klimt is elected president of the newly founded Vienna Secession.

1898 Klimt designs the poster for the Secession’s first exhibition and produces numerous illustrations for the periodical Ver Sacrum.

His painted likeness of Sonja Knips is the first in a row of modern female portraits.

1900 The presentation of the first faculty painting,

Philosophy, in the Secession elicits fierce controversy. The majority of the audience and press regard Klimt’s unprecedented rendering of human figures in the nude as scandalizing. The painting is awarded a gold medal at the Paris World’s Fair.

1901 The presentation of the second faculty painting, Medicine, provokes increased criticism of Klimt’s art.

1902 Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze in the XIVth Exhibition of the Vienna Secession (Beethoven Exhibition) marks his adoption of a new, monumental style. His treatment of the human figure is characterized by an emphasis on the motifs’ outlines, and by geometricized postures and gestures.

1903 Klimt travels to Italy and is fascinated by the mosaics in Ravenna. The faculty painting Jurisprudence is presented at the XVIIIth Exhibition of the Vienna Secession, a monographic show devoted exclusively to Klimt. The foundation of the Wiener Werkstätte by Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser, and Fritz Waerndorfer introduces a new phase of the Viennese Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art.

1905 Klimt buys back his faculty paintings, which were ultimately rejected. In 1945, they fall victim to a fire in Immendorf Castle in Lower Austria, together with other principal works by the artist.

1908 Klimt opens the Vienna Kunstschau, which presents sixteen masterpieces of his Golden Period, including The Kiss and the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer.

1909 In the second international Vienna Kunstschau, Klimt, as the exhibition’s president, is again represented with several of his new works. His journey to Paris brings new inspirations and marks the end of the Golden Style.

1910 Because of his erotic nude drawings exhibited at the Vienna Galerie Miethke, the artist is accused of pornography.

1911 At the International Art Exhibition in Rome, Klimt wins the first prize for his painting Death and Life. He travels to Brussels to supervise the installation of the mosaic frieze designed by him for the Stoclet Palace.

1912 Klimt moves into his last studio in Hietzing.

1912/13 Klimt takes part in exhibitions in Dresden, Budapest, Munich, and Mannheim. His painting and drawing style becomes more liberal.

1914–18 Official art life is paralyzed because of the First World War. Klimt participates in the exhibition of the League of Austrian Artists at the Berlin Secession together with Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, and Anton Faistauer.

1916/17 Klimt is appointed honorary member of the Academies of Fine Arts in both Dresden and Vienna. He makes preparations for a group exhibition in Stockholm.

1918

On 11 January, Klimt suffers a cerebral stroke and dies on 6 February. He is buried in the cemetery of Hietzing.

More images from exhibition:

Gustav Klimt

Lady with Plumed Hat, 1908

Ink, graphite, red pencil, white gouache

Gustav Klimt

Portrait of a Lady with Cape and Hat, 1897-98

Black and red chalk

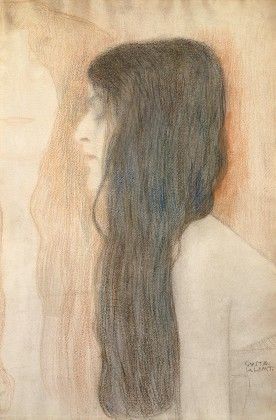

Gustav Klimt

Girl with Long Hair, with a Sketch of "Nuda Veritas", 1898/99

Black and colored chalk

Private collection, courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd., London

Gustav Klimt, Reclining Girl and Two Studies of Hands (Study for "Shakespeare's Theater", Burgtheater, Vienna), 1886/87. Black chalk, stumped, white heightening. Albertina, Vienna.

Gustav Klimt

Lying Nude, 1912/13

Red Pencil