The Grimaldi Forum Monaco will be presenting « From Chagall to Malevich, the revolution of the avant - garde » , exhibition July 12 - September 6, 2015 produced in connection with the Year of Russia in the Principality of Monaco. The exhibition will be one of the outstanding events of the Year of Russia celebration which will run through - out 2015.

This wide - ranging exhibition will bring together major works by great artists who from 1905 to 1930 represented the avant - garde movement in Russia. They shaped an unprecedented modernity, distinguishing themselves totally from what had been known before: Altman, Baranoff - Rossin, Burliuk, Chagall, Chashnik, Dymch its - Tolstaya, Ender, Exter, Filonov, Gabo, Gavris, Goncharova, Kandinsky, Kliun, Klucis, Kudryashov, Larionov, Lebedev, Lentulov, Lissitzky, Mashkov, Malevich, Mansurov, Matiushin, Medunetsky, Mienkov, Morgunov, Pevsner, Popova, Puni, Rodchenko, Rozanova, Shevchenko Stenberg, Stepanova, Sterenberg, Strzeminski, Suetin, Tatlin, Udaltsova, Yakulov.... These artists were the forerunners of the tremendous upheaval in the way of thinking about, seeing, and representing the reality.

If academism was still around , these young creators, both in Moscow and in St. Petersburg, could not be satisfied with that vision of the past. The arrival of electricity, of the railroad, of the automobile, of the new means of communication forged a new language. The artists would impose a vision that corresponded to what was around them, to what they were experiencing, to who they were themselves.

New ideas flourished. It became clear that there was no halting these great upheavals in a society that was also insisting on change. New ways of representation, until then unknown began to appear, and to become inseparable from this current of modernity that expressed the impact of the discoveries taking place in those first years of the 20th century, in literature, music, dance as well as in plastic arts. The sounds, the words, the form jostled and turned upside down commonplace ideas.

Between a strait - laced, outdated world and the innovators of this period, the gulf was enormous. In this shaken - up world, artists developed a language that stripped away the old and made way for the future. Different movements emerged, outside of all convention, creating schools or movements that illustrated the energy and wealth of creativity at the beginning of the 20th century: Impressionism, Cubism, Futu rism, Cubo - futurism, Rayonism, Suprematism, Constructivism — movements producing new and unknown forms of representation, indelibly interwoven with their era. Such is the essential outline of this great story of the “avant - garde” artists who shook up centuries of convention and academism.

Self-Portrait with White Collar

Marc Chagall, French (born Russia), 1887 - 1985

Date:

1914

In order to present a subject of such scope, the exhibition curator Jean - Louis Prat has obtained important loans from major Russian institutions: the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the Pushkin Museum and the Tretyakov State Gallery in Moscow. Other great Russian museums such as the Nizhny Novgorod, Astrakhan, Krasnodar, and Tula museums, all of which benefited from deposits of art at the beginning of the October 1917 Revolution, have also been contacted and have agreed to make exceptional loans. Some of the important European museums such as the George Pompidou Center in Paris complete this prestigious list. The exhibition will bring together 150 major works.\

The

departure point of the exhibition coincides with that of the upheaval of

Russian society at the beginning of the 20th century. Traditional Russia still

existed; artists such as Konchalovsky, Machkov, Malevich (at the beginning of

his career) were producing works in the classical style. Those artists, who

were portraying a society genuinely linked to the foundation of Russian

culture, intuitively sensed the profound changes to come.

This

exhibition therefore begins in 1905, date of the first great change that took

place in Russia’s history: the “Bloody Sunday” revolt in St. Petersburg. All

these artists understood that an inevitable change in society was at hand,

change that would soon lead to the 1917 October Revolution.

And

in fact, the personal paths of these artists contributed to the changing

spirit: they travelled abroad, they went to Paris—Baranoff-Rossin, Tatlin,

Chagall and Kandinsky—they were all in quest of new ideas.

For

one, Konchalovsky was very interested by the work of Derain and Vlaminck; for

another, Machkov probably saw andadmired the work by Matisse. All these artists

recognized the need to create a new style and these new ways of seeing

becamethe very basis of this revolution—it started slowly and then became

inevitable.

In

contrast, other painters, writers and poets were far more advanced in their

approach, fruit of the many exchanges between Russia and France. Matisse had

just decorated the interior of the residence of Shchukin, a great collector who

lived in Moscow. As Shchukindid with his home, so other private homes opened

their doors every weekend in Moscow to display to a chosen public the works of

Picasso, Braque and Gris that had been purchased in Paris by these rich

industrialists.

The

artists discovered and invented new forms, new colors, a new way of seeing the

world. Marinetti, an Italian poet and a born revolutionary, came to give

conferences in the Russian capital and sketched out what would be the very

foundation of an important pictorial revolution. Art bore witness to this new

world, taking into account a period, which was changing. Progress was

ineluctable. It became accepted that a car could be as beautiful as a painting.

And if the car is in movement, well then art can also embrace such movement.

The machine inevitably creates innovation, and so new artistic schools

appeared, changed by dreams and utopias.

Larionov,

Goncharova and Udaltsova began to express themselves by borrowing ideas from

the French Cubists. They had been to see them or seen their works exhibited in

Moscow, they had sometimes worked in their studios or the work of those French

artists had been acquired by Russian collectors.

Russian

artists took inspiration from what they saw and in turn created an

extraordinary nucleus, a genuine fermentation of new ideas leading to the

founding of different artistic movements: that of Rayonism with Larionov and

Goncharova, that of Futurismaround David Burliuk. For the first time,

associating a fixed image from Cubism to an imagein movement from Futurism gave

rise to a typically Russian movement: Cubo-Futurism.

Other

artists such as Chagall, who was unconnected to any school, gave expression to other

dreams. Chagall’s work spoke of tradition coming from old Russia. He painted other

images, inspired by the Orient ,using other colors. His work, using themes of

Jewish culture, was in a whole new style all his own and furnished a new

substrata to history that was in the process of being created. The Theater of

Jewish Art, painted in 1920 after the 1917 Revolution had already broken out, is

a meaningful example of Chagall’s new way of representation. Chagall was named

director of the Vitebsk school in 1917 and returned to the country where he was

born (known now as Belorussia). He created a school there at the request of

Lunacharsky, minister of culture. Naturallyhe put into practice the tenets of a

new way of thinking, of seeing, of writing, of painting. He brought in other

important artists who were following other artistic paths such as Lissitsky and

Malevich.

Creating

his own language, Malevich brought in new ideas, turning upside down the poetic

vision of Chagall’s work. The Suprematist school that Malevich founded soon

became an obstacle to any possible understanding with Chagall. The rupture was

inevitable. Chagall left for Moscow to create the Theater of Jewish Art,t hat

extraordinary place where all the great artists of his time would come to participate

in exercising their arts: writers, poets, directors, actors. Chagall created his

fresco, Introduction to the Theater of Jewish Art (which is eight meters long),

an astounding painting that proves to what extent he remained faithful to that

Russian and Jewish culture which is the very basis of his inspiration.

As

for Malevich, he continued to embody a language completely opposite of

Chagall’s but one just as extraordinary: he created abstract art, an artistic

expression totally unknown until then and which compelled attention. And so a

new school came into being--Suprematism.

At

the same time, other artists such as Tatlin created anothers chool using new

materials, that of Constructivism. The exhibition of the Grimaldi Forum sheds

light on this opposition and complementarity between Suprematism and

Constructivism. The artists who participated in that particular part of history

such as Rodchenko, Tatlin, Kliun, Rozanova, Popova and many others, participated

also in that revolution of the spirit. In Russia in the twenties, the thirst

for change originated in and existed side by side with the new modernity.

From

the start of the Revolution, Kandinsky, who at the beginning of the 20thcentury

had developed his own innovative style, was in charge of a commission to

distribute to museums in the provinces the work of all those artists who were

considered as revolutionaries and who worked and exhibited in Moscow and St.

Petersburg. The State bought works that were sent to Rostov-sur-le Don, to

Perm, to Astrakhan and Krasnodar etc....to ensure that the heart of Russia

would discover the revolutionary message.

Rapidly,

those in power began to distort this noble message, permeating it with ideology

whose motivations did not necessarily correspond to the liberty of style of the

artists. The latter finally understood that they could no longer exercise their

rights as creators in an environment where ideas were being imposed upon them.

Many of them left Russia beginning in the 1920s and moved to Berlin, Paris and

the United States: Larionov, Goncharova, Kandinsky, Chagall, Baranoff-Rossin.

Confronted

by a Russian art that had become more and more official, imposing its vision

upon the artists, those who remained behind such as Malevich were “prisoners.”

And so he wrote, “I prefer a sharp pento a dishevelled brush.” They would

return to figurative painting, though of figuresdevoid of faces. As for

Filonov, he closed himself off into a completely different language,

impenetrable to any understanding by the revolutionaries in power The death of

Mayakovsky in 1930, emblematic poet of the Revolution, marked the end of an

exceptional and unique adventure, the end of dreams and of utopias...

The

exceptional aspect of the exhibition comes from the loan of major works from

Russia, works which rarely leave the national galleries: the Pushkin Museum,

the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg. Of

course the arrival of The Theater of Jewish Art by Marc Chagall and of its

seven large panels is definitely an event, and the same can be said for the

“Quadrangle”, the “Cross” and the “Circle” by Malevich. But all the works are

of this quality. For this exhibition, there has been agenerous and exceptional

collaboration by Russian’s prestigious institutions, not to mention the museums in

the provinces whose works are mostly little seen, being rarely accessible even

for the most curious of travellers! Add to that, the loans from the Pompidou

Center such as the “Tower” by Tatlin, the works from the famous

Costakis collection in Greece, and those from the Thyssen Museum in Madrid, and

of course from many private collections.

Movements

Neo-Primitivism:

Movement of Russian painting inaugurated between 1907 and 1912 by D. and V.

Burliuk, Larionov, Gontcharova, which advocated a return to naïve forms of

popular imagery (loubok), icons, store signs, in reaction to French painting

judged to be too predominant.

Rayonism:

First abstract non-figurative movement. Larionov was its creator withhis works

of 1913 thatrepresent only networks of rays by which he wished to show “space

between objects.” Larionov made a distinction between a “realist rayonism” and

an “abstract rayonism” where the pictorial elements are orchestrated in an

autonomous way without explicit reference to the object, as in Red Rayonism

(the model of the functioning of music being its reference).

Cubo-Futurism:

Russian pictorial movement that beginningin 1912 made the synthesis of Parisian

Cubism, of Italian Futurism and of Neo-Primitivist principles. Its major

representatives were Tatlin, Malevich, Olga Rozanova, Alexandra Exter, Liubov

Popova.

Suprematism(Souprématizm): Name given by Malevich to his creation

without-object presented at the Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, at

Petrograd in 1915.

Suprematism

was also a philosophy, strictly monistic, presented in an important corpus of

treaties and articles written by Malevich. With the exception of a few booklets

published at Vitebsk, these texts remained unpublished until the end of the

1960s, date when Suprematism was rediscovered.Russian

Constructivism:

Artistic movement originating in Soviet Russia which dominated the 1920s.

Although already beginning in1921, within the framework of the Muscovite

Inkhouk(institute of artistic research),the Constructivist work group had been

created (Rodchenko, Medunetsky, Stepanova, Gane and G. Stenberg), but the name

only appeared in public for the first time in January 1922 in a booklet

entitled Constructivists that presented a exhibition by Medunetsky, and V. and

G. Sternberg.

The

Constructivist movement had its roots in a practice begun in the West with

Cubism and Futurism and was carried on in Russia through multiple artistic

experiences: Cubo-Futurism, Rayonism, Suprematism, Tatlin’s reliefs or

Malevich’s research on a “constructed scenic space”, or those of Yakulov

(interior decoration of the Café Pittoresque in 1917). Proclaiming the death of

easel painting in favour of an industrial and constructive art, Russian

Constructivism reached into all areas of the artistic environment: books,

posters, furnishings, architecture, textiles, clothing, theatre....It triumphed

in Berlin in 1922 with the exhibition Erste russische Kunstausstellungat the

Van Diemen Gallery,and later in Paris in 1925 at the International Exposition

of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts

Typical works

Kazimir

Malevich

Self Portrait Circa 1908

Gouache

and ink on paper 46,2 x 41,3 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

As

1910 dawned, Malevich, just thirty years old, abandoned his symbolist period,

an important period in Russia during the last part of the 19thcentury. He

painted two self-portraits, both dating from the same period, one now in the

Tretyakov State Gallery in Moscow and the other belonging to the State Russian

Museum. The two celebrate his convergence with the group of Russian painters

known as “Jack of Diamonds” that advocated in their works Cezanne’s principles,

and Fauvism during the period between 1910 and 1917.

Beyond

the representation of the artist himself, we can see in this self-portrait the

representation of the painter in him, bearing all the colors of the palette.

Malevich wrote some ten years later, “in the artist blazes all the colors of

all the tints, his brain burns, in him are ignited the rays of colors that

advance clothed in the tints of nature

Farmers

Gathering Apples

by

Natalia Gontcharova,

is

in the continuity of the movement begun by the brothers Burliuk and Natalia Gontcharova

with her companion Mikhail Larionov in the period between 1907 and 1912. This

movement advocated the return to the plastic principles of popular art. The

erudite perspective is replaced by expressive compositions of simplified forms

that develop a trivial and provincial theme. The influence of Gauguin was one

of Gontcharova’s main sources of inspiration.

Beyond

the Fauve palette, with its intense and brilliant colors, one finds in the

painting’s composition the sacralisation of farm work, the representation of

profile “à la Egyptian” as well as the enlargement of the feet and hands, a

characteristic mark of the French master. But it was in bringing to her works

inspiration anchored in Russian popular art that Gontcharova rendered them

profoundly remarkable.

Kazimir

Malevich

Perfected

Portrait of Ivan Kliun 1913

Oil

on canvas 111,5 x 70,5 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Presented

for the first time at the Youth Union (1913-1914), the Perfected Portrait of

Ivan Vassilievich Kliunkovis one of the most representative examples of

Cubo-Futurism in Malevich’s work but also in the Russian painting of the

period. With devastating humour perfectly in harmony with the spirit of the

times, Malevich constructs a portrait of his friend and most faithful adherent,

in deliberately neglecting all physical resemblance. The contour of the face

remains visible but the anatomic details have been reduced to a minimum. In

keeping with the alogism advocated by Malevich in 1913, identifiable elements

(saw, portion of log architecture, smoke rising from a chimney) appear here and

there without any logical link between them: projections of the interior world

of the model.

With

the portrait of Kliun, Malevich showed a profound interest in futurist research

whose dynamic interpenetration of the human world and objects he retained.

Nevertheless the chromatic scale and the reduction of forms come from the

tradition of Russian popular art.

Natalia

Goncharova

The

Cyclist 1913

Oil

on canvas 79 x 105 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg© 2015, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg/ ©

ADAGP, Paris 2015

The

Cyclist is considered as a genuine archetype of Russian futurism in the way it reconciles

realism with the perception of dynamism and movement. The figure of the

velocipedist is perceived as if through a window on which appears a fragment of

an inscription in Cyrillic alphabet. In the back, one can see buildings, including

a large café recognizable by its sign on which appear the silhouettes of a beer

mug and a bottle. Even incomplete, the words šlâ [pa](hat), šëlk(silk) and

nit[ka](thread) are perfectly identifiable and remind us that Natalia Goncharova,

along with several of her compatriots, explored the world of textiles, thus

enhancing decorative arts. During her first retrospective in Moscow in 1913,

her projects of textiles and embroidery were presented alongside her paintings.

The static character of the silhouettes of arms, legs, back, wheels, the bike

chain, accentuate the sensation of speed. The letter «Я» («I» in Russian) of

the word “hat” stands out clearly. Isolated, it refers to the subject “I” and

can appear as a discreet signature by the painter.

Mikhail

Larionov

Portrait

of Igor Stravinsky 1915

Oil

on canvas 60 x 50 cm

Collection

V. Tsarenkov Courtesy of Vladimir Tsarenkov private collection / © ADAGP, Paris

201538

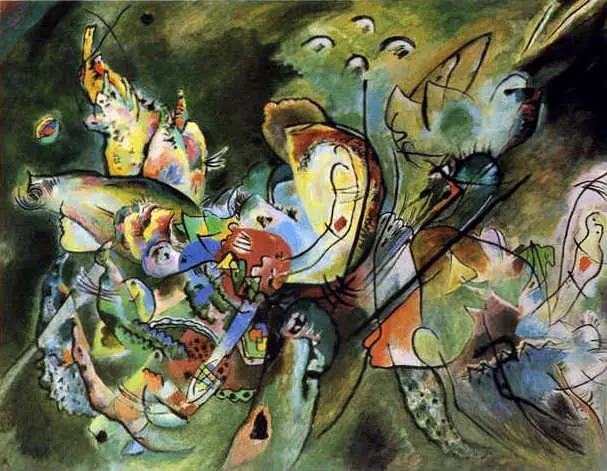

Overcast (1917)

Oil on canvas, 105 x 134 cm (41.3 x 52.8 in)

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

A bilingual scientific catalogue, richly illustrated, including essays by specialists on avant - garde art as well as notices and bibliographies on the artists and the different movements of that period will be published for the event.

The

year 1917 was, according to Kandinsky, “dramatic.” Married in February, he

thought of building himself a house and a big studio in Moscow but the October

Revolution put an end to his project. Within the framework of the confiscations,

he lost the building of 24apartments that he had owned. “We were largely

compensated for the losses during the time of the Revolution,” wrote Nina

Kandinsky. “... art and culture experienced a revolutionary spring that

relegated to the shadows everything that had ever been done in Russia in that

domain. All the artists saw themselves suddenly being offered quasi-unlimited

possibilities.”

During

those seven Russian years (1915-1921), Kandinsky held important posts. As

director of the National Commission of Acquisitions, he contributed to the

creation of twenty-two museums in the provinces. During that period, his

artistic production was characterised by a strange heterogeneity. Some

paintings abound with schematic figurative elements; others present an increasing

geometrization indebted to Suprematism and Constructivism. The composition

however always dominates over the construction and intuition over reason.

Alexander

Rodchenko

Abstraction (Rupture) Circa 1920

Oil on canvas140,2 x 136 cm

Greek State

Museum of Contemporary Art –Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki© Greek State

Museum of Contemporary Art –Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki / © ADAGP, Paris

201541

Between

1916 and 1920, Rodchenko explored all the possibilities that combinations of

lines and colors offered him, seeking to create never-before-seen formal

associations. Having launched himself into abstraction without ever having

passed by the deconstruction of the object, his art by-passed the designs of

Cubism, of Cubo-Futurism, of Suprematism, to delve into a knowledge of the

world. Rodchenko’s problematic during his brief career was focused by turns on

drawing, color and text. Here, one notices a very particular attentiveness to

the texture of the pigment. With Abstraction Rupture, the artist does not speak

about the world, but the painting speaks about itself.

Chagall

and the Jewish Art Theatre

Introduction to the Jewish theatre 1920

Tempera on canvas toile,

gouache 284 x 787 cm

Marc Chagall

The Dance 1920

Tempera on canvas,

gouache 213,3 x 107,8 cm

Marc Chagall

The Music 1920

Tempera on

canvas, gouache 212,3 x 103,2 cm

Tretyakov State Gallery, Moscow© Tretyakov State

Gallery, Moscow/ © ADAGP, Paris 2015

The

creation of the décor for the Jewish Art Theatre provided Marc Chagall with an

intense joy. It was created in 1920 and shows a powerful and dream-like world.

In a saraband full of verve and life, Chagall painted The Introduction to the

Jewish Art Theatre, a very big panel of almost eight meters long that, like a

huge comic strip ahead of its time, provides a space of liberty in astunning

display of people and colours. A whirlwind of energy responding to the painter’s

dreams. Subtle nuances fill these great works with familiar and comical details

that Chagall often borrowed from daily life and from his imagination.

The

whole of The Jewish Art Theatre constitutes one of the great events of the

pictorial creation of the 20thcentury. The seven panels of which it’s

made are now a part of the Tretyakov State Gallery collection in Moscow. Marc

Chagall signed these works upon his return to the USSR in 1973, the first

voyage he had made to his native land since his departure in 1922.

Suprematism

Kazimir

Malevich

The

Black Square Circa 1923

Oil

on canvas 106 x 106 cm

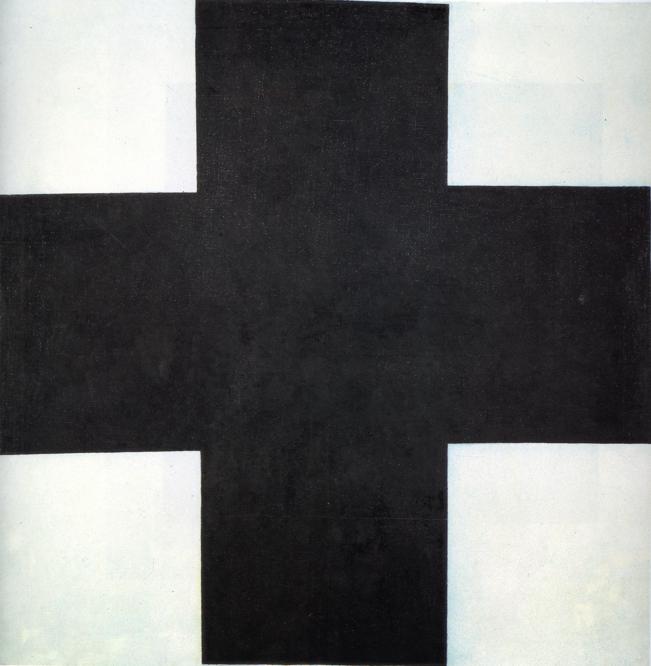

Kazimir

Malevich

The

Black Cross Circa 1924

Oil

on canvas 106 x106,5 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

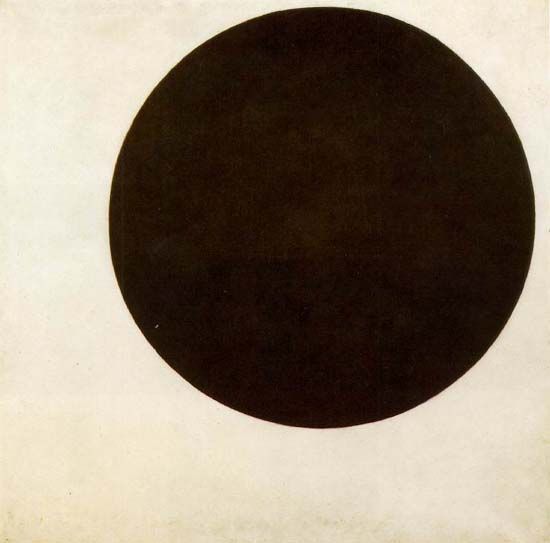

Kazimir

Malevich

The

Black Circle Circa 1925

Oil

on canvas 105,5 x 106 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The

Black Square, the Black Circle, and The Black Cross make up a sort of triptych,

including Kazimir Malevich’s epigraphic compositions, all painted, according to

the specialists, around the end of the 1920s. However, the author dated them

1913, which would mean the works were made at the moment of the appearance of

Suprematism and at the first showing of The Black Squareduring the famous “Last

Futurist Exhibition 0.10” in 1915 at Petrograd.

It’s

not simply by chance that Malevich presented the first variant of The Black

Squareat the exhibition “0.10” like an icon, hanging it, according to Russian

custom, in the “good angle” (the right angle of the room). The icon was the

sign of a new epoch, it was thus that his contemporaries perceived The Black

Square, probably in recalling Malevich’s words, “I have only one naked

frameless icon, of my time (like a pocket)....”The Black Square became, during

the artist’s lifetime, a certain symbol of Malevich’s art, the sign of the

Suprematism that he had created.

Mikhail

Matiushin

Movement

in space 1921

Oil

on canvas 124 x 168 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Movement

in space is among those works by Matiushin in which he expresses his theory of

the interaction of colors and of the “enlarged vision” that he formulated

definitively at the beginning of the 1920s. That became the working basis of

the Zorved group that he created with Boris Ender in Leningrad. Intending to go

beyond pictorial impressionism that portrayed only the phenomenological and

fragmentary aspect of light, Matiushin multiplied experiments on color and

visual perception that oneperceives under different conditions. Movement in

space is the most brilliant example of the interaction that colors can have

between themselves. According to Matiushin’s theories, color has nothing

definite about it. It depends on neighbouring colors, on the forms that contain

it, on the intensity of the lighting. His research led in 1932 to the publication

of the Color Tables.

Boris

Ender

Extended space

Canvas

on oil 69,1 x 97,8 cm

National

Museum of Contemporary Art-Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

During

the 1920s, in opposition to the Futurist cult of the machine, Boris Ender and

his sisters, Maria and Xenia Ender, actively participated in the development of

the organicist theory defended by Matiushin and his wife Elena Guro whom the

artist had met in 1911. In 1923 Ender became a member of Zorved (See-Know), a

research laboratory where work was being doneon the widening of man’s ocular

vision.

In

his pictorial works, Boris Ender sought to show color in movement as well as

its mutations according to the enlarging “point of view.”His work derives from

non-figuration (the object is submerged in a colored magma) and from

abstraction with its myriad of small touches of colors made into a complex

mosaic. The very warm colors combining blues, yellows, reds and greens

underline the artist’s very Slavic expressionist palette

The

end of utopias

Kazimir

Malevich

The

Sportsmen 1930-1931

Oil

on canvas 142 x 164 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The

painting The Sportsmen retains the geometric base in the construction of the

figures, elaborated by Kazimir Malevich at the beginning of the years 1910 and

enriched, in the new phase, by an increasing interest inthe pictorial style. The

rhythm of the composition and the colors of this painting show the influence of

icon painting and fresco. In particular it brings to memory the canonical

images of the rows of the Apostles on the walls of ancient churches and the

iconostases, but also the figures from the Futurist opera “Victory over the

sun”(1913), in demonstrating the continuity of the creative evolution of the

master, as attests the inscription on the back of the painting: “Suprematism in

the shape of sportsmen.”

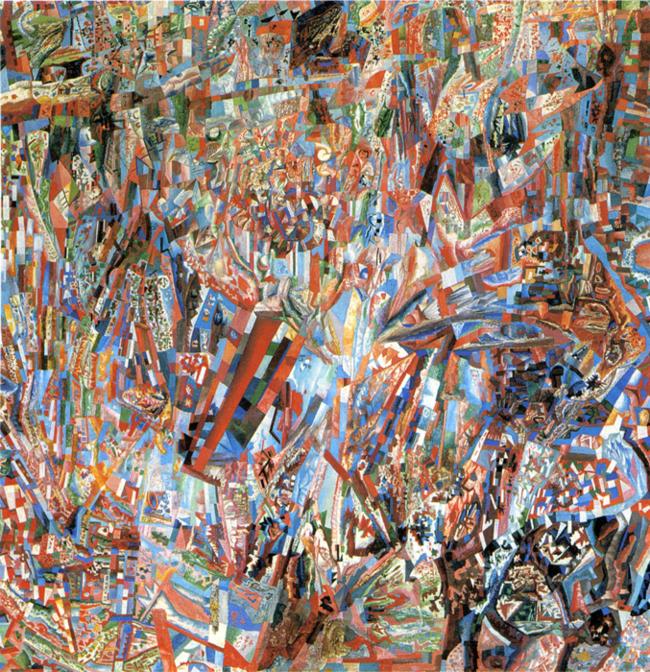

Pavel

Filonov

The

Formula of Spring 1927-1928

Oil

on canvas 250 x 285 cm

State

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The

Formula of Spring sums up all of Filonov’s creation, creation where the world is

in perpetual metamorphosis. Made up of a intertwined network of colored units,

in the way of tessera of mosaics, there is no empty space on the surface of the

painting. It is the place of germination, of growth and of the opening outof

the pictorial into the grandiose polyphony of atoms. The geometry is not that

which consists, as in Cubism, of defining the object through several points of

view, but that of the Universe that implies superior dimensions to those known

by the Euclidian world.

Showing

affinities with Matiushin’s “organicism”, Filonov’s analytical method assumes

the auto-development of the form and its metamorphosis. Describing himself as

“the artist of Universal Flowering”, Filonov believed in the purely scientific

method of his work which made possible, according to him, “to include within the

paintings life as biological process.

A bilingual scientific catalogue, richly illustrated, including essays by specialists on avant - garde art as well as notices and bibliographies on the artists and the different movements of that period will be published for the event.