ALBERTINA

16 September 2015 – 8 January 2016

When Georges Seurat died unexpectedly in 1891 at the age of 31, his older colleague Camille Pissarro already had an inkling that Seurat’s “invention” was to have consequences for painting “that would be highly significant later on”. And indeed, with just a few pictures, Seurat had founded a style that would play a pioneering role in Modern Art: Pointillism.

This fascinating art movement is now the focus of a high-calibre exhibition at the Albertina, a presentation that completes the story of Modern Art with the significant chapter of Pointillism as its midwife: 100 selected masterpieces by the main representatives of this style, Seurat and Signac, as well as impressive paintings, watercolours, and drawings by modernist masters who were fascinated by this pointed technique—figures such as Van Gogh, Matisse, and Picasso—illustrate Pointillism’s breath-taking radiance and seminal impact.

Seurat, Signac, Van Gogh, organised in cooperation with the Kröller-Müller Museum, tells the success story of Pointillism from its creation in 1886 to its effects on the early 1930s. Beginning with the ground-breaking early works by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Théo van Rysselberghe, this exhibition draws an arc from Paul Signac’s and Henri-Edmond Cross’s transformation of the points into small squares and mosaics all the way to the masterpieces of Vincent Van Gogh, the vibrant colours of the Fauves, the decoratively placed dots in the cubist works of Pablo Picasso, and the abstract works of Piet Mondrian.

This comprehensive presentation sheds light on the unique metamorphosis of the pointillist dot and for the first time makes a theme of those achievements of the pointillists that were subsequently harnessed by modernism.

Between Realism and Abstraction

The painters to whom we now refer to as “pointillists” due to their unusual techniques set out in 1886 to challenge the avant-garde tendencies of the impressionists, which had by then become de rigueur. And the subsequent development of painting in Paris towards the end of the 19th century would show just how right Pissarro’s prescient judgment was: the emphasis on surfaces and stylisation as well as the motionlessness and detachment of the depicted figures in the works by Seurat tell of increasing pictorial autonomy and, accordingly, of an abstraction of both content and form. This would soon move between two poles: the picture’s geometrisation and its ornamentalisation by means of arabesques.

In reducing their painterly handwriting to the smallest possible artistic statement—the dot—Seurat, Signac, Pissarro, and Rysselberghe not only distanced themselves from the impressionists’ reproduction of fleeting moments, but also used their approach to question the entire centuries-old norm of painting according to nature in the form of brushstrokes. Points in solid colours, which the pointillists placed close together in keeping with the optical principle of colour mixing, generated a hitherto-unknown radiance and a multitude of chromatic impulses. It was thus that the realistic view of the world gave way to depictions of a synthetic reality—and in one fell swoop, the doors were wide open for Modernism.

Following Seurat’s death, it was above all his colleague Signac who develop the pointillist technique further: together with Henry-Edmond Cross, Signac increased luminosity, intensified colour contrasts, and coined the term “Divisionism”. His small, systematically placed points soon developed into lines meant to appear as a mixture of colours when viewed from an appropriate distance.

His

small, systematically placed points soon developed into lines meant to appear

as a mixture of colours when viewed from an appropriate distance. With this

more liberal approach, Signac liberated painters from the obligation to use

dots, and it was thus that a younger generation—including Henri Matisse and his

circle as well as Piet Mondrian—ultimately broke out of Seurat’s rigid system.

An important intermediary in this

development was Vincent van Gogh, an outsider and brief adherent of Pointillism

who set off in new directions. Van Gogh at first took up Seurat’s ideas with

enthusiasm:his pallet became brighter and more luminous, and an abundant flurry

of dots found entry into his landscapes. But the systematically dotted style

never played a truly central role in Van Gogh’s output. The artist soon adopted

a freer form of expression that better matched his nature: “It is working with points

and similar elements that I hold to be the real discoveries; but we must

already be at pains to ensure that this technique, just like any other, does

not itself become a general dogma.” He said this in 1888, at which point he

began countering the cool and rational pointillist style with his own individual

expression and emotion.

Matisse, Mondrian, and Picasso

Something similar can be seen in the reception of Divisionism in the oeuvre of Henri Matisse. The founding Fauve had turned to this technique in two steps: 1897 saw him experiment with comma-like, impressionist micro-structures that are not dissimilar to Pissarro’s mode of painting, and in 1898 he intensified colours and contrasts, which subsequently led to a valid implementation of the divisionist method in term of both chromatic division and the use of dots.

Soon, Van Gogh, Matisse, and the Fauves moved Piet Mondrian, as well, to turn away from Pointillism. Under the influence of the luminist Jan Toorop, Mondrian used his paintings to deal above all with light effects, relying on motifs and an expressive power that had already become established in the works of Van Gogh and the anarchic art of the Fauves.

In the works of Pablo Picasso, as well, Pointillism and its pioneering ideas did not go unnoticed. At altogether three junctures in his career—1901, 1914, and 1917—the Spanish artist dealt playfully with the output of Seurat and integrated points into his own work. The first time he did so, Picasso was motivated by his desire to conform to the times; later on, though, he used loosely arranged points to develop the decorative surfaces of so-called “Rococo Cubism.” His final take on the technique was the masterpiece

Return from the Baptism, which amounted to a precise and entirely consummate quotation.

Matisse, Mondrian, and Picasso

Henri Matisse

Parrot Tulips

Something similar can be seen in the reception of Divisionism in the oeuvre of Henri Matisse. The founding Fauve had turned to this technique in two steps: 1897 saw him experiment with comma-like, impressionist micro-structures that are not dissimilar to Pissarro’s mode of painting, and in 1898 he intensified colours and contrasts, which subsequently led to a valid implementation of the divisionist method in term of both chromatic division and the use of dots.

Soon, Van Gogh, Matisse, and the Fauves moved Piet Mondrian, as well, to turn away from Pointillism. Under the influence of the luminist Jan Toorop, Mondrian used his paintings to deal above all with light effects, relying on motifs and an expressive power that had already become established in the works of Van Gogh and the anarchic art of the Fauves.

''Spanish Dancer,'' 1901, by Picasso. Credit Nahmad Collection, Switzerland

In the works of Pablo Picasso, as well, Pointillism and its pioneering ideas did not go unnoticed. At altogether three junctures in his career—1901, 1914, and 1917—the Spanish artist dealt playfully with the output of Seurat and integrated points into his own work. The first time he did so, Picasso was motivated by his desire to conform to the times; later on, though, he used loosely arranged points to develop the decorative surfaces of so-called “Rococo Cubism.” His final take on the technique was the masterpiece

Return from the Baptism, which amounted to a precise and entirely consummate quotation.

The Art of Sounding the Flat Surface: Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat started out as a

draughtsman. A disciple of Ingres’s Neoclassicism, he painstakingly outlined

his figures with distinct contours and carefully modelled them with delicately shaded

transitions. But it was not long before his drawing style would change

radically. Using his fingertip, he rubbed the creasy black pigment of the Conté

crayon onto the coarse surface of the drawing paper. Depending on the pressure,

larger or smaller amounts of the pigment would adhere moreor less thickly to

the grainy material. There is no stroke and no line in these drawings to guide

the spectator’s eye, just the light shining forth vaguely from the dark

expanse.

Seurat fathomed the deepness of black. Absorbing the light, the

surfaces of his drawings shimmer in their porous blackness. Subtle contrasts of

light and dark reduce the figures to bodiless silhouettes. Seurat recorded

unspectacular motifs on the outskirts of the city –passers-by and strollers he

ran into in the Parisian suburbs. Simplifying them to geometric shapes, he used

these figures to study the contrasts of light and dark. Still adhering to an

Impressionist brushwork, Seurat also sketched an idle bourgeoisie on a Sunday afternoon

on the Island of La Grande Jatte near Paris on small panels of wood. When

transferring these motifs to the canvas, he translated them into small dots for

the first time, placing them closely next to one another.

The Order of Geometry: Paul Signac

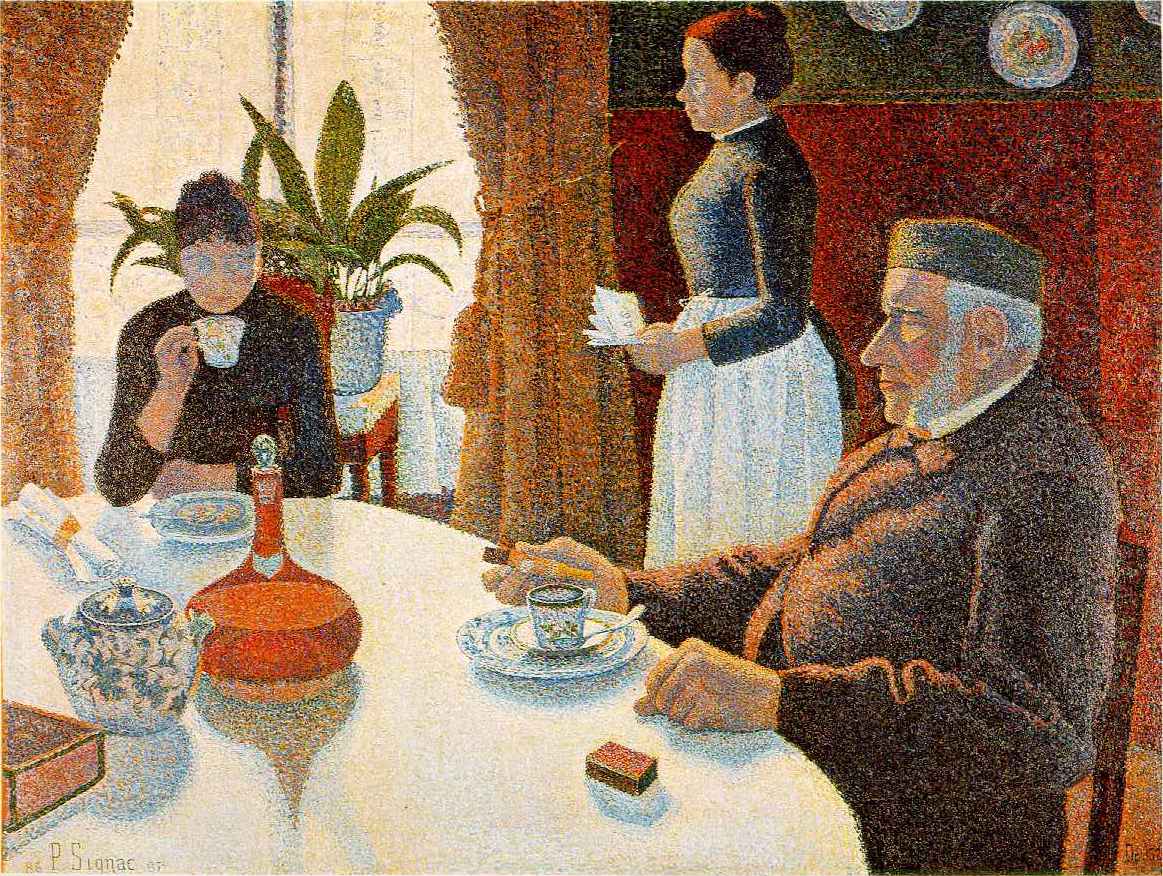

On Sundays the Signac family had a mute

luncheon. After relishing his café-rhum,the grandfather would read the paper

brought in by a maid.

which presents the Parisian bourgeoisie in the act of public self-display during leisure time. Signac’s composition, on the other hand, offers an intimate glimpse of the domestic bourgeois environment. Everything issubordinate to an austere pictorial geometry: circular, rectangular, and cuboid shapes are distributed across the surface of the picture; the flat figures are inscribed in an orthogonal system of horizontals and verticals and rendered in strict profile or frontal view. No interaction between the protagonists and no narrative moment interrupt the silence.

Paul Signac’s Dining Room was made in response to

Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,

which presents the Parisian bourgeoisie in the act of public self-display during leisure time. Signac’s composition, on the other hand, offers an intimate glimpse of the domestic bourgeois environment. Everything issubordinate to an austere pictorial geometry: circular, rectangular, and cuboid shapes are distributed across the surface of the picture; the flat figures are inscribed in an orthogonal system of horizontals and verticals and rendered in strict profile or frontal view. No interaction between the protagonists and no narrative moment interrupt the silence.

Paris–Brussels: Hotspots of Pointillism

Spreading rapidly beyond Paris,

Pointillism reached the Brussels art scene, which readily welcomed avant-gardism.

Following the example of the Parisian group of ‘independent’ artists (‘Les Indépendants’),

Belgian artists also joined forces to fight academism. The group Les Vingt (‘The

Twenty’)maintained close relations to the French avant-garde and immediately

embraced Pointillism with great enthusiasm.

In 1887, Seurat exhibited his

painting A Sunday Afternoon on

the Island of La Grande Jatte in

Brussels. Impressed by the new style, the Belgians Henry van de Velde, William

Alfred Finch, and Théo van Rysselberghe and the Dutchman Jan Toorop broke free

from Impressionism practically overnight. They reduced their motifs to abstract

shapes, stylised their objects, and simplified their compositions to geometric

constructions of what seemed to be halftone surfaces.

Regardless of the motif,

Van de Velde and Toorop covered their pictures with flimsy veils of brightly shining

dots, thereby achieving an almost abstract simplicity. Toorop also admired

Japanese woodblock prints and the art of Paul Gauguin. Curved lines and

sweeping arabesqueswere used to set the dotted planes apart from one another.

Some

artists felt confined by Pointillism’s decorative dictate. Van de Velde became

a designer and architect, and Finch switched to ceramics. Only Théo van

Rysselberghe held on to the Pointillist painting technique. His palette was

close to that of his friend Paul Signac, with whom he undertook extensive

sailing trips along the French Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

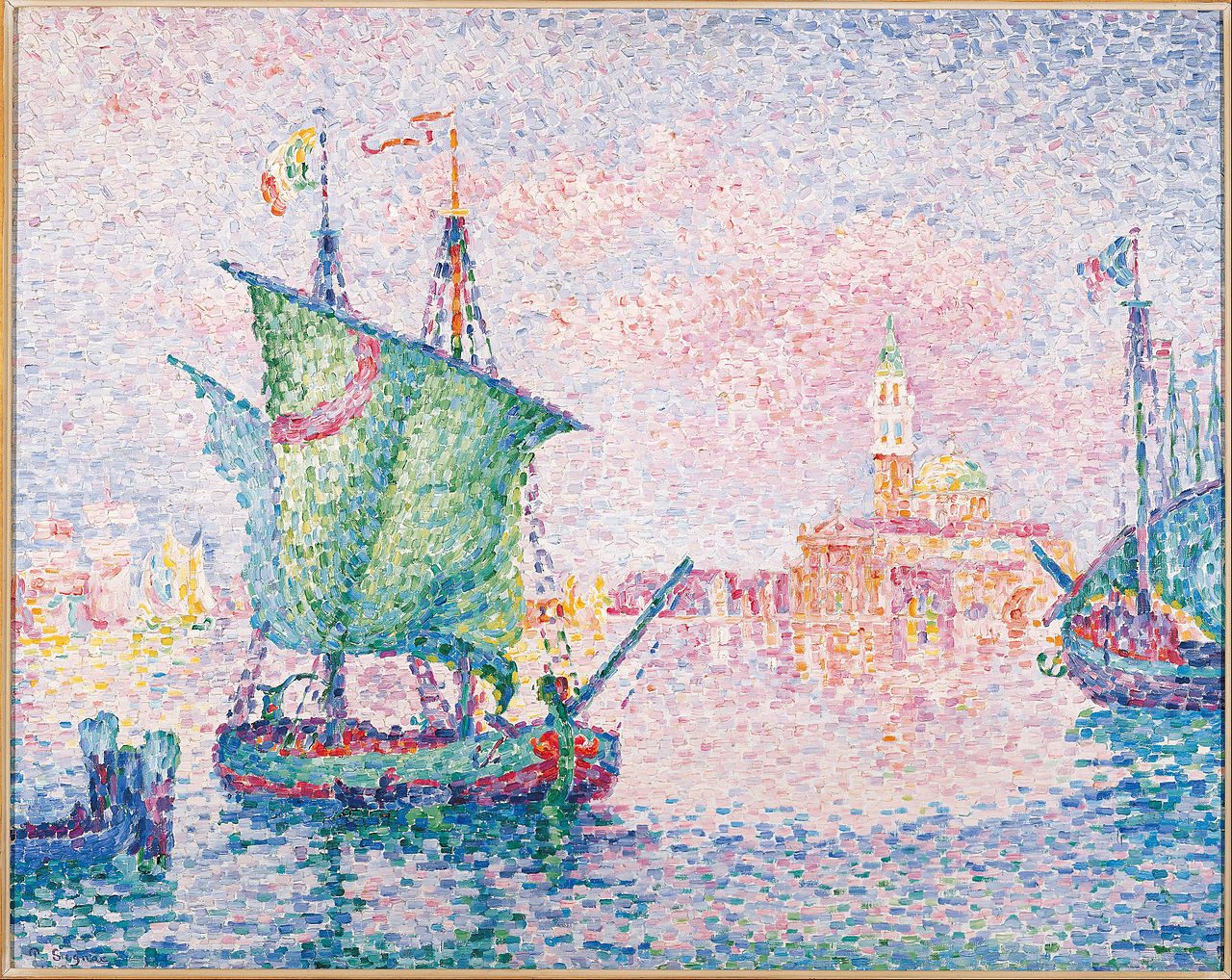

Paul Signac - Venice, The Pink Cloud, 1909

Paul Signac was a close friend of

Georges Seurat, his senior by four years, and after Impressionist beginnings adopted

Seurat’s Pointillism. However, although employing the same painting technique, he

pursued different goals. Yet both artists strove for a new pictorial harmony

and hence for a liberation of the image from nature: this autonomy of art would

eventually pave the way for modernism. Whereas Seurat achieved a homogeneous

pictorial surface by using related colours and focusing on rhythm and line,

Signac sought to achieve visual harmony through the interplay of contrasting,

intensely brilliant colours. He divided the surface into geometrically abstract

or stylised, arabesque-like shadows on the one hand and naturalistically

rendered motifs on the other.In the nineteenth century there was a widespread

ambition to create a harmony in painting that was related to that of music.

Many of Signac’s contemporaries were guided by the idea that their pictures were

‘harmonies of tones of colour’; the American painter James Abbott McNeill

Whistler, for example, entitled his works as ‘harmony’, ‘symphony’, or

‘nocturne’. Signac borrowed from him by assigning opus numbers to his

paintings, thereby emphasising the abstract and musical qualities of his

pictures. Paul

Signac was the mouthpiece of Pointillism in France and won over many other

artists for the movement. He established contacts with the Belgian group Les

Vingt and Théo van Rysselberghe, who became the leader of the Belgian

Pointillists.