The Met Fifth Avenue, Gallery 199

April 24–July 30, 2017

- Still LifeA still life is a representation of people. —Irving Penn In still life—his first and perhaps deepest love in photography—Penn established a notable discipline of rigor and compression that stood him in good stead for his long career with the camera. Still lifes were among his earliest assignments after joining Vogue in 1943. When composing these pictures he played the role of storyteller but left out the human protagonists. All that remains are their traces—an alluring smear of lipstick on a brandy glass, a burnt match. Penn constructed these (and all of his) photographs through a bravura act of reduction, challenging the viewer to apprehend their internal order and read them for signs of life.

Theatre Accident, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1984

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Still Life with Watermelon, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Salad Ingredients, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1984 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

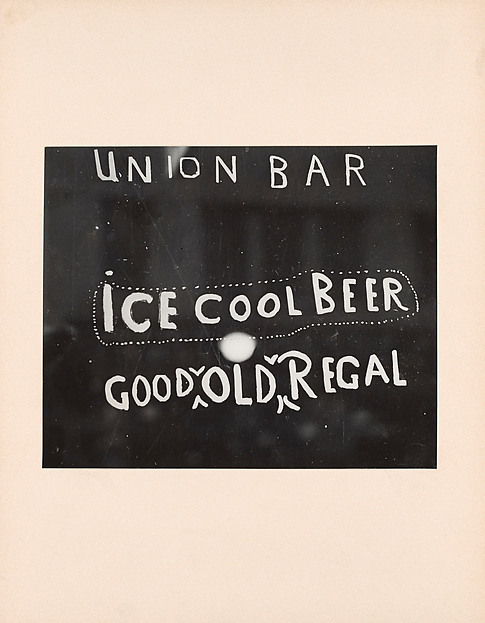

Early Street PhotographsPenn acquired his first camera—a twin-lens-reflex, 2¼-inch-square-format Rolleiflex—in 1938 while working as an assistant to Alexey Brodovitch, the legendary graphic designer and art director at Harper’s Bazaar. Penn’s earliest photographs are studies of nineteenth-century shopfronts, hand-lettered advertisements, and street signs in Philadelphia and New York. With their visual clarity and vernacular content, these pictures reflect the subject matter of Depression-era, documentary-style photography. Frequently, Penn focused in close to his subject when framing the image in the camera and then cropped it more extremely in his finished print.

Penn continued this style of picture-making on a short trip through the American South in 1941 and during the following year, which he spent painting and photographing in Mexico.

O’Sullivan’s Heels, New York, ca. 1939 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Union Bar Window, American South, 1941 Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Beef Still Life, New York, 1943 Chromogenic print, 2003Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

After-Dinner Games, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1985Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationPulquería Decoration, Mexico, 1942 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationW La Libertà, Italy, 1945 Gelatin silver print, 2001 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationPenn returned from Mexico at the end of 1942 and spent thefollowing year at Voguewhere, as he said, he “became [a] professional photographer” while working for Alexander Liberman, the fashion magazine’s art director. Except for a short break in 1944–45 to servein Europe and India as a staff photographer and ambulance driver with the American Field Service, during which this photograph was made, Penn remained with the magazine forthe next six decades. Existential Portraits, 1947–48Irving Penn: CentennialAfter serving in the war, in 1945 Penn returned to his work at Vogue. To infuse the magazine with culture and boost his associate’s budding career, art director Alexander Libermanasked Penn to make a series of portraits of personalities. The sitters were selected for him, but the set, lighting, and conduct of the sessions were up to the photographer.Not yet thirty and hardly known, Penn had to find a way to direct the sessions with his famous subjects. He found that cornering them between two angled stage flats was an effective way to control the interaction and amplify their responses. The unfinished nature of the set highlights the artifice of studio portraiture. Likewise, the sitters’ sometimes disproportionate body parts (such as Joe Louis’s narrow shoulders and enormous feet) call attention to the foreshortening distortions of the camera’s lens. Another minimal schema Penn used was an old carpet tossed over boxes. Like the no-exit corner, this barren no-man’s-land seemed appropriate to the psychic tenor of the postwar moment. By 1948 these stark, astute portraits had made Penn’s name.Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationJerome Robbins, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationElsa Schiaparelli, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationBottom, left to right Alfred Hitchcock, New York, 1947Gelatin silver printPeter Ustinov, New York, 1947 Gelatin silver printPromised Gifts of The Irving Penn FoundationMrs. Amory Carhart, New York, 1947 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationSpencer Tracy, New York, 1948 Irving Penn: CentennialGelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationJoe Louis, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationGeorge Grosz, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver print Truman Capote, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAudioguide #302Dusek Brothers, New York, ca. 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationLe Corbusier, New York, 1947 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationGeorge Jean Nathan and H. L. Mencken, New York, 1947Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIgor Stravinsky, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of TheIrving Penn FoundationBallet Society, New York, 1948 Platinum-palladium print, 1976 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationCharles James, New York, 1948 Gelatin silver print, 2002Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationCarl Erickson and Elise Daniels, New York, 1947Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationSalvador Dalí, New York, 1947 Irving Penn: CentennialGelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIn Vogue, 1947–51Once Penn’s prowess in portraiture was established, Alexander Liberman groomed him for fashion. “Alex thought I was a bit of a street savage,” Penn recalled. He was instructed to buy an evening jacket and to attend “the collections,” the highly anticipatedshowings of Parisian couture. However, the crush of competing photographers and excited editors at these events overwhelmed Penn. He preferred to work away from the fray, without fancy settings or accoutrements, and, if possible, in a daylight studio. Forthe 1950 collections, therefore, a Paris studio was found, as well as a theatrical curtain that served as a neutral backdrop. In an old building with neither electricity nor water and up several flights of rickety stairs, the top-floor studio had north-facing windows. Penn was delighted with the spartan place and pearly light, with the superbly wrought fashions by Balenciaga and other designers, and with his models. He praised one talented model, Lisa Fonssagrives, a former dancer who had accompanied himfrom New York, for her finesse of draping and pose. Their knowing collaboration, detectable in her gaze, resulted in an unparalleled suite of pictures. caption:Irving Penn, Irving Penn’s Studio in Paris, 1950. Gelatin silver print. The Irving Penn FoundationVogueCoversBetween 1943 and 2004 Penn produced photographs for 165 Voguemagazine covers, more than any other artist to date. Perhaps the most famous is the April 1, 1950, issue (in the middle), a snazzy composition in black and white featuring Jean Patchett. In the bottom row, Suzy Parker holds one of Penn’s Rolleiflex cameras, the type he used for most of the photographs in this gallery and throughout his working life. The woman in profile wearing gray fur (and in a light blue hat and dress, and with binoculars) is Lisa Fonssagrives, the most famous and highest paid model of the day.Glove and Shoe, New York, 1947 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationDior Dress (Dorian Leigh), New York, 1949 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIrving Penn: CentennialThe Twelve Most Photographed Models, New York, 1947Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationOwing to his evident talents with both still-life arrange-mentand portraiture, Penn was tasked with Vogue’s group portraits. These bravado feats of chore-ography were tough assignments, and given the compet-itiveness of many fashion models, this one could have been harrowing. Yet Penn relished this particular job, not only for its challenges but also because it was here that he met Lisa Fonssagrives (back row, center left, in profile). They were married in London three years later.The Tarot Reader (Bridget Tichenor and Jean Patchett), New York, 1949 Gelatin silverprint, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationKerchief Glove (Dior), Paris, 1950 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationBlack and White Fashion with Handbag (Jean Patchett), New York, 1950Gelatin silver print,2003Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationModern Family—The Broken Pitcher, New York, 1947Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationBalenciaga Sleeve (Régine Debrise), Paris, 1950Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationGirl with Tobacco on Tongue (Mary Jane Russell), New York, 1951Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationSpanish Hat by Tatiana du Plessix (Dovima), New York, 1949Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIn the days when well-dressed women wore hats, Tatiana du Plessix was a highly regarded milliner with a design studio at Saks Fifth Avenue. She was also the wife of Alexander Liberman. The model, Dovima, posed for Penn and most every photographer of the era. Cocoa-Colored Balenciaga Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), Paris, 1950 Platinum-palladium print, 1980Irving Penn: CentennialPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationRochas Mermaid Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), Paris, 1950Platinum-palladium print, 1980Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAudioguide #303Balenciaga Mantle Coat (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), Paris, 1950Platinum-palladium print, 1988Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationWoman with Roses (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in Lafaurie Dress), Paris, 1950 Platinum-palladium print, 1968Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationVogue Fashion Photograph (Jean Patchett), New York, 1949Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationLarge Sleeve (Sunny Harnett), New York, 1951Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationMan Lighting Girl’s Cigarette (Jean Patchett), New York, 1949 Gelatin silver print, 1983Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationWoman in Chicken Hat (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), New York, 1949 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationWith the war and rationing over, in the late 1940s and early 1950s the pages of American fashion magazines exploded with chic styles from Paris, London,and New York. Penn responded to the new looks—the cinched waists, full skirts, and, at times, eccentric millinery—with equal flair. PrintmakingPenn believed that there were many ways to interpret his negatives during the printing process, as seen here in four distinct variations of the same photograph, Girl Drinking, New York, 1949. The earliest example shown, a traditional gelatin silver print (far left), dates from about 1960, ten years after the photograph appeared in color in Vogue; the latest, another gelatin silver print (far right), was made by Penn forty years later. The two Irving Penn: Centennialversions in the middle are platinum-palladium prints from 1976 and 1977. Penn taught himself this laborious contact-printing process, long considered out-of-date, in the 1960s, when picture magazines had begun their decline. Using negatives he enlarged to the size of the prints he wished to make, and artist papers he selectively mounted to aluminum and coated with multiple layers of platinum and palladium, Penn executed editions from his current and older work.He experimented with highlight and shadow values, tones, and paper surfaces as well as color and scale. While most photographers try for consistency inprinting, variations were freedom for Penn: each denoted a different thought about what the picture should express. It followed that there could be many versions of “perfect.”Girl Drinking (Mary Jane Russell), NewYork, 1949Gelatin silver print, ca. 1960Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationGirl Drinking (Mary Jane Russell), New York, 1949Platinum-palladium print, 1976Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation Girl Drinking (Mary Jane Russell), New York, 1949 Platinum-palladium print, ca. 1977 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Girl Drinking (Mary Jane Russell), New York, 1949Gelatin silver print, 2000

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationCuzco, 1948

In late November 1948 Vogue sent Penn to Lima, Peru, for his first fashion assignment on location. After completing the sessions with Jean Patchett, he traveled alone to Cuzco, the splendid city high in the Andes. Penn quickly found a local photographer’s daylight studio to rent and produced, in three days, hundreds of portraits of residents and visitors from nearby villages, all wearing their traditional woolen clothing. The photographs reveal a couturier’s instinctive grasp of a garment’s weight, pattern, and texture and a stage director’s knack for posing subjects. The Cuzco series also established the fundamental visual and psychological principles behind the portraits Penn would make in distant corners of the world over the next twenty-five years. Although virtually all of the Cuzco photographs that Penn later printedare in black and white (both gelatin silver and platinum-palladium prints), heused color transparency film for much of his work in Peru. “Christmas at Cuzco,” published by Voguein December 1949 Irving Penn: Centennial(see case nearby), featured a suite of eleven color portraits with an unsigned introduction written by Penn. Young Quechuan Man, Cuzco, 1948 Gelatin silver print, 1949Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIn Cuzco, Penn photographed both residents and visitors who came to the city from nearby villages with goods to sell or barter at the Christmastime fiestas. Many arrived at the studio to sit for their annual family portraits. Penn later recalled that they “found me instead of him [the local photographer] waiting for them, and instead of paying me for the pictures it was I who paid them for posing.”

Many Skirted Indian Woman, Cuzco, 1948 Platinum-palladium print, 1989Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Cuzco Father and Son with Eggs, 1948 Platinum-palladium print, 1982Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Mother and Posing Daughter, Cuzco, 1948 Platinum-palladium print, 1989Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Young mothers arrived at Penn’s rented studio with their newborns strapped in little hammocks on their backs; shepherds and porters came dressed in colorful, striped ponchos and woolen capes; and street vendors from near and far showed up with their wares, including straw hats, newspapers, and fresh eggs from the valleys far below the city. Penn posed these sitters with his distilled awareness of the poetics of available light and his sense of how to delicately tilt a head in order to strengthen a chin, shadow an ear, or animate the eyes.

Cuzco Children, 1948 Platinum-palladium print, 1968 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAudioguide #305

Newspaper Boy, Cuzco, 1948 Gelatin silver print, 1949 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Street Vendor Wearing Many Hats, Cuzco, 1948 Irving Penn: Centennial Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationThe woman in this photograph poses in an ensemble typically worn during mourning rites.Sitting Enga Woman, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationEnga Tribesman, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationWoman with Three Tribesmen, New Guinea, 1970Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationMan with Pink Face, New Guinea, 1970 Silver dye bleach print, 1993Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAlthough Penn worked in both color and black and white when traveling the far corners of the globe, he produced almost no color prints of the pictures. That visual experience was left to the printed pages of Vogue,which published them from 1967 to 1971 (see case nearby). Penn made this trial print of a New Guinea man two decades later, by which time doubts about color photography’s capacities as an art form had evaporated. Penn evidently preferred the black-and-white medium, however, and did not make further color trials. This print has never before been exhibited.

\

Man with Pink Face, New Guinea, 1970 Platinum-palladium print, 1978Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation New Guinea

Man with Black Beard, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 2005Promised Giftof The Irving Penn Foundation

Tambul Warrior, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn

New Guinea Man with Painted-On Glasses, 1970 Platinum-palladium print, 1979 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Three New Guinea Men Painted White, 1970Platinum-palladium print, 1979Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Morocco, 1971

If Cuzco was the start of Penn’s project to photograph remote peoples of the world in situ, then Morocco was the end of the journey. For this last expedition, Penn set up his tent in the town square of Guelmin, a southern city home to an ancient camel market and known as the “Gateway to the Desert.” Penn wrote that he invited the guedradancers to pose: “Those chosen sat, eyes fixed on the lens, enjoying the camera’s scrutiny yet themselves impenetrable.” After the trip, Penn began printing photographs from his travels for his book Worlds in a Small Room(1974).Among the Moroccan subjects, he selected several images that would speak eloquently in black and white. Veiled in their burkas and seated in rocklike immobility, the figures are enigmatic. Despite the challenging, wind-whipped conditions, Penn was able to extract mesmeric monuments of stillness, a remarkable demonstration of patience and expertise in visualizing a desired outcome.Woman with Three Loaves, Morocco, 1971 Gelatin silverprint, 1990Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationTwo Guedras, Morocco, 1971 Platinum-palladium print, 1977 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationFour Guedras, Morocco, 1971Platinum-palladium print, 1985Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationTwo Women in Black with Bread, Morocco, 1971Platinum-palladium print, 1986Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Dahomey, 1967

Penn visited the newly independent Republic of Dahomey, present-day Benin, shortly after photo-graphing an African art exhibition in Paris in 1966. It was for this and subsequent trips to Africa and the Pacific that he designed his portable studio, made of an aluminum skeleton covered by a special windowed nylon tent. His first sitters in Dahomey were children and young women living in the lagoon town of Ganvié, known to Westerners as the “Venice of Africa.” The trip to Dahomey was inspired by widely circulated photographs of legendary female warriors who had been infamously exhibited at world’s fairs in the nineteenth century. Seen within this context, Penn’s photographs may evoke unsettling narratives of colonial history. They reveal a dichotomy of wills, a tension between the self-possession and occasional defiance of the sitters and the artist’s overt direction of their postures.

Dahomey Children, 1967Platinum-palladium print, 1980 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationThree DahomeyGirls, One Reclining, 1967 Platinum-palladium print, 1980 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAudioguide #313Five Dahomey Girls, Two Standing, 1967 Platinum-palladium print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationScarred DahomeyGirl, 1967Platinum-palladium print, 1984 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIn Benin, the carefully arranged cicatrization marks (raised scar formations) on a woman’s body are traditional signs of beauty and spiritual empowerment.Three AsaroM ud Men, New Guinea, 1970 Platinum-palladium print, 1976 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation“Adornment for Gods, for Love, for War,” Vogue, December 1970Offset lithographyThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Joyce F. Menschel Photography Library“The Quest for Beauty in Dahomey,” Vogue, December 1967Offset lithographyThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Joyce F. Menschel Photography LibraryPenn: Centennial“The Veiled Mystery of Morocco,” Vogue, December1971Offset lithographyThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Joyce F. Menschel Photography Library“The Spectacular Highlanders of New Guinea, SouthPacific,” Vogue, December 1970Offset lithographyThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Joyce F. Menschel Photography

Library Time Capsules

The portraits and photographs of style in this room range in date from the 1960s to the first decade of the twenty-first century. The expressions of sixties modernity—such as model Marisa Berenson in a brazen bridal outfit and author Tom Wolfe’s BeauBrummel flair—embody the swinging “youthquake” years. The lighter tone of these images yields, in works from more recent decades, to nostalgic fantasies and suggestions of lost innocence and futile vanity. While Penn’s sense of beauty had always included the inevitability of decay, the death of his wife (in 1992) and his own advancing years affected his perspective, turning his late fashion photography into a brilliant mirror of life’s transience.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, New York, 1993 Gelatin silver print, 2002 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Truman Capote, New York, 1965 Platinum-palladium print, 1968Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1986 (1986.1206)

Joan Didion, New York, 1996 Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation Vogue,September 15, 1967 Offset lithography The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Late Still Life

Penn managed to stay creative throughout his sixty-six years at Vogue because the editorial demands continuously evolved and because he engaged in personally nourishing side projects exploring still life, his first love.

Between 1975 and 2007 Penn produced four major series: Street Material, Archaeology, Vessels, and Underfoot. They are compositions of old bottles and vases, and of detritus—gutter rubbish, metal parts, rags, bones, and decaying fruit. In his off-hours, Penn often sketched or painted the same objects (see case nearby).

Like assembling a jigsaw puzzle, but in three dimensions, Penn’s still-life habit was a form of creative meditation. Engrossed with the materials, he considered the imaginative realms residing in the life of shoe leather, a fissured crock, or a flower petal. As sensitive to the charge emitted by objects as he was to the spark from individuals, Penn listened to their messages and photographed them singly or arranged in conversations, as human surrogates. These assemblages were then disassembled and painstakingly rearranged to form other constellations. Pictured are moments of rest in the ongoing flow of Penn’s active mind; they make permanent a cycle of constant change and offer further proof of the artist’s exceptional, lifelong fecundity.Three-Tiered Vessel, New York, 2007 Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIrving Penn: Centennial Mouth (for L’Oreal), New York, 1986 Dye transfer print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationSingle Oriental Poppy, New York, 1968 Dye transfer print, 1987 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Hell’s Angel (Doug), San Francisco, 1967 Gelatin silver print, before 1975 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationBirgitta Klercker —Long Hair with Bathing Suit, New York, 1966Gelatin silver print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationBalenciaga Rose Dress, Paris, 1967 Gelatin silver print,2002 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationUngaro Bride Body Sculpture (Marisa Berenson), Paris, 1969 Gelatin silver print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAudioguide #314Naomi Sims in Scarf, New York, ca. 1969 Gelatin silver print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIrving Penn: CentennialNicole Kidman in a Chanel Couture, Lagerfeld’s Mannish Tweed Jacket, New York, 2004 Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIssey Miyake Staircase Dress, New York, 1994Platinum-palladium print, 1997 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationIn The 1960s Vogue asked Penn to photograph flowers, a subject that had not attracted him previously but became a passion for The duration of The commission. He wrote: “My preference is for flowers considerably after They have passed that point of perfection, when They have already begun spotting and browning and twisting on Their way back to The earth.”

The images were published in special Christmas issues from 1967 to 1973.

Three Poppies ‘Arab Chief’, New York, 1969 Dye transfer print, 1992 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationPeony ‘Silver Dawn’, New York, 2006 Inkjet print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationUnderfoot IX, New York, 2000Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationCup Face, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationMud Glove, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationCamel Pack, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium printPurchase, Nancy and Edwin Marks Gift, 1990 (1990.1000)Deli Package, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationCup, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationParade, New York, 1980 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationStill Life with Shoe, New York, 1980 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationThree Steel Blocks, New York, 1980 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationStill Life of Nine Pieces, New York, 2005 Inkjet printing, watercolor, and gum arabic on paper The Irving Penn Foundation

IRVING PENN QUOTES“I myself have always stood in awe of the camera.I recognize it for the instrument that it is, part Stradivarius, part scalpel.”

“I don’t think I was overawed by the subjects. I thought we were in the same boat.”

“A beautiful print is a thing in itself.”

“The daylight . . . is the light of Paris, the light of painters.It seems to fall as a caress.”

“Photography is just the present state of man’s visual history.”

“To me personally,photography is a way to overcome mortality.”