de Young museum

through May 23, 2021

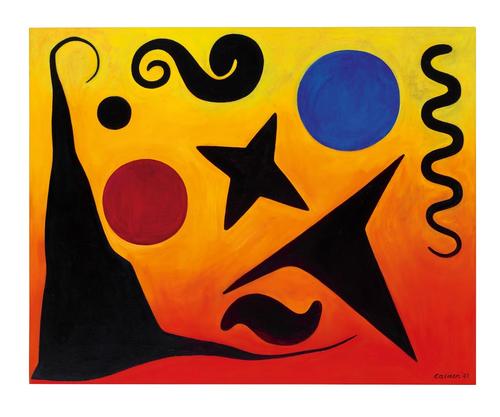

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco are presenting the U.S. debut of Calder-Picasso at the de Young museum, now through May 23, 2021. Conceived by the artists’ grandsons Alexander S. C. Rower and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, it is the first major museum exhibition to explore the artistic relationship between Alexander Calder and Pablo Picasso, two of the most innovative and influential artists of the 20th century. In more than 100 paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photographs—including many iconic works—the exhibition presents a compelling visual conversation centering around the artists’ exploration of the void, or the absence of space, which they defined from the figure through to abstraction.

“Calder-Picasso provides an in-depth investigation of the relationship between two of the most influential artists of the 20th century,” states Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “We are delighted to share this fascinating exhibition with audiences on the West Coast. It reaffirms the revolutionary impact of their work as each grappled with the representation of form, space, and time in art—and in doing so, redefined the conception of art itself.”

Calder-Picasso invites visitors to explore a visual dialogue of works from the mid-1920s to the early 1970s. In this time, Calder sought to capture the unseen and unknown forces that lie beyond traditional physical dimensions in order to express what he called grandeur immense, or “immense grandeur.” In the same period, Picasso, who described his works as pages from his diary, was engaged in fusing the personal with the universal and was determined to achieve “a deeper likeness, more real than real, thus becoming sur-real.”

“Through his mobiles, Calder animated sculpture, embraced chance as a crucial artistic element and engaged the viewer in a dynamic dialogue with the ever-evolving artwork. Exploring the concept of metamorphosis while alternating between representation and abstraction, Picasso revealed the infinite potential inherent in both styles—often in the same work of art,” states Timothy Anglin Burgard, Distinguished Senior Curator and Ednah Root Curator in Charge of American Art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Portraits of the artists’ studios will reveal deeply personal environments that offer windows into each artist’s creative process, as well as their respective psychological outlooks. Adding to our understanding of the connection shared between the two artists, the exhibition will also explore one of the artists’ four in-person meetings. While their first encounter was in 1931 at Calder’s premiere Paris exhibition of his abstract sculptures, the exhibition explores his second, at the Paris World’s Fair (1937), where Picasso exhibited his painting Guernica (1937) and Calder exhibited his sculpture Mercury Fountain (1937) in the Spanish Pavilion. Two further documented meetings took place in Antibes in 1952 and Vallauris in 1953.

Calder-Picasso will showcase a wealth of pioneering mobiles, stabiles, standing mobiles, paintings, prints, and drawings by Calder, juxtaposed with major paintings, sculptures, and drawings by Picasso, drawn largely from the extensive holdings of the Calder Foundation, Musée national Picasso-Paris, and the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. Additional loans will come from the Centre Pompidou; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery; Minneapolis Institute of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Tate Britain; Whitney Museum of American Art; and private collections.

In detail

Thematically arranged, Calder-Picasso will take visitors on a journey through the Herbst Exhibition Galleries that reveals compelling resonances and parallels between these great artists, as well as the unique visions that make each distinctive.

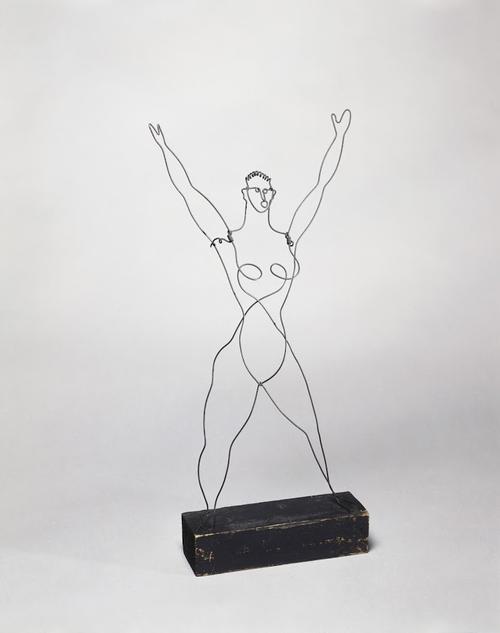

Calder and Picasso were both engaged by the relationship of volume to space. In the exhibition’s opening gallery, Calder’s Ball Player (ca. 1927) captures the silhouette of the figure as he reaches out into space in a moment of focused action, radiating kinetic energy through the slight trembling of the wire lines. Picasso’s Figure (Project for a Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire) of 1928 embodies the artist’s attempt to make “a statue out of nothing, out of emptiness.”

The next gallery, “Drawing in Space”—a phrase coined by critics for Calder’s wire sculpture in 1929—explores the two artists’ use of line to separate volume from void. Calder’s wire proto-mobile, Aztec Josephine Baker (1930), which sways with air currents, captures the dazzling energy and dynamism of the legendary African American dancer and cabaret performer who took Jazz Age Paris by storm in the late 1920s. Picasso also experimented with wire and his Figure (1931), seems to conflate a human figure with a geometric object that recalls an artist’s easel.

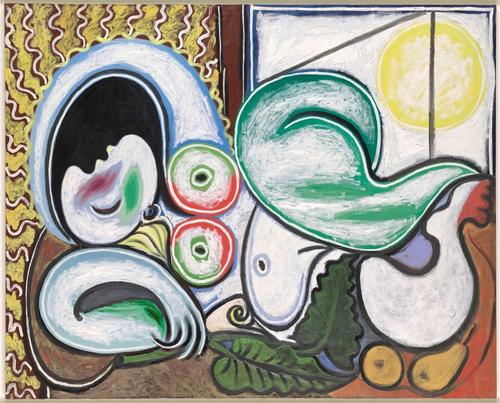

In “Capturing the Void,” Calder’s and Picasso’s works explore the idea of activating negative space as an essential component of their compositions. With Croisière (1931), Calder depicts unifying yet disparate forces in his non-objective work: solidity and transparency, stasis and activity, volume and void. The upraised left arm of Picasso’s Nu couché (Reclining Nude) of 1932, which frames a half-moon profile against a black void, finds a resonant echo in the wire lines encircling the voids in Calder’s sculptures.

Works in “The Void and the Volume / In Suspense” reveal that both Calder and Picasso were deeply engaged with ideas concerning the articulation of volume within the space of the canvas, and in Calder’s case, expanding works beyond their two-dimensional confines. Calder’s Little Yellow Panel (1936) explores the idea of animating two-dimensional painting with a projecting three-dimensional element in motion. Picasso’s Femme assise dans un fauteuil rouge (Woman Seated in a Red Armchair) of 1932 transforms the subject into a floating arrangement of bone and stone shapes that would collapse in the real world.

In “Sculpting the Void,” Calder’s and Picasso’s works utilize a sculptural vocabulary to shape voids into sensed and seen elements in their compositions. Calder’s standing mobile Four Leaves and Three Petals (1939) employs gracefully slender wire rods and organic sheet-metal shapes to sculpt the surrounding space. Picasso’s Femme dans un fauteuil, (Woman in an Armchair), April 2, 1947, depicts the female sitter as partially transparent and suggests that the voids in her body assume equally significant sculptural form.

“Vanitas” represents a post–World War II period of rebirth. Calder’s mobile Dispersed Objects with Brass Gong (1948) ingeniously introduces randomly generated sound as an essential element, while Picasso’s Still Life with Skull, Leeks, and Pitcher (1945) uses a skull, bone-like leeks, and a pitcher painted with the French flag colors to suggest the dawn of a new era.

In “Making and Deconstructing,” Calder and Picasso construct and deconstruct their subjects and forms to visualize invisible worlds. Key works include Calder’s mobile Scarlet Digitals (1945), a sculpture that projects into places that it doesn’t occupy; its three disparate movements present a shifting presence of absence that is alive with gestures. Picasso’s iconic Bull’s Head (1942), a bronze sculpture made from a discarded bicycle seat and handlebars, reveals the artist’s fascination with the process of distillation to access the truth of the subject.

Works in “Gravity and Grace” have substantial mass yet seem to defy the rules of gravity. Calder’s perfectly balanced Tightrope Worker (1944) is an unusual excursion into solid and fully three-dimensional sculpture that still retains the artist’s preoccupation with movement, while Picasso’s Vase with Flower (1951) challenges conceptions of mass and weight by depicting a soft and fragile flower in hard and durable cast bronze.

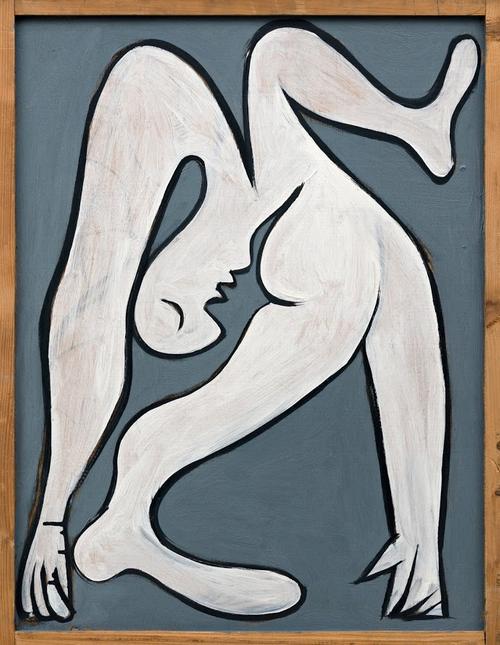

The exhibition’s final section, “Folding and Piercing,” will challenge traditional definitions that equate sculpture with solid three-dimensional mass. The sheet-metal standing mobile Louisa’s Valentine (1955), with a miniature mobile animating the heart-shaped void, was made by Calder as a valentine for his wife. Picasso’s Woman with Outstretched Arms (1961), sculpted out of metal yet retaining the lightness of paper, flattens the female form into silhouettes and plays on the dialogue between substance and void.