March 5–May 30

The Clark Art Institute’s latest exhibition presents four centuries of war imagery from Europe and the United States in As They Saw It: Artists Witnessing War, on view March 5–May 30, 2022. Spanning European and American art from 1520–1920, the exhibition of prints, drawings, and photographs shows how artists have portrayed periods of military conflict, bringing war off the battlefield and into the homes and lives of those who were often at a far remove from the scene. The exhibition is on view in the Eugene V. Thaw Gallery of the Clark’s Manton Research Center in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Visual media have long played a key role in documenting war. Especially for those far from the front, eyewitness imagery is crucial to understanding what may be happening on the battlefield. Yet artists’ depictions of the wrenching conditions and consequences of warfare may even transcend their historical origins to become lasting monuments to suffering and sacrifice. This exhibition brings together a diverse selection from the Clark’s holdings: both pro- and anti-Napoleonic imagery (including Francisco de Goya’s Disasters of War); Civil War photographs and wood engravings; and multiple perspectives on World War I. The exhibition features a special selection of recently acquired photographs of Black Americans in military service, documenting the contributions of people who have long been underrepresented in the historical record.

“This exhibition gives us the rare opportunity to look at four hundred years of imagery that often shaped public awareness and sentiment related to conflicts that changed the course of history,” said Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director of the Clark. “From documenting battle scenes to capturing the depth of grief and suffering that accompanies war, these deeply moving images put a human face on the sometimes abstract idea of conflict and remind us of the toll of war.”

Meslay noted that “to honor all those who have served their nation, we are welcoming all veterans, active-duty military members, and their families with free admission to the Clark from March 5 through May 30 in hopes that they will visit us to see this exhibition.”

The exhibition presents more than forty-five images by artists including Mathew Brady, Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet, Albrecht Dürer, Roger Fenton, Francisco de Goya, Winslow Homer, Georges Jeanniot, Édouard Manet, and James Tissot. These artists were not simply bystanders. Many of them served as soldiers or had been expressly commissioned as war artists. To a great extent, artists’ nationalities and backgrounds influenced the version of events they chose, or felt compelled, to present. Even those who worked far from the front lines were engaged in one side or the other of a battle of images—with representations of war playing a substantial role in how the parties to a conflict were perceived and how their actions were interpreted, both in the moment and long afterward.

“This exhibition accounts for both military and civilian experiences of war and presents a great diversity of perspectives, including some which have been historically underacknowledged,” said exhibition curator Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. “As They Saw It emphasizes the subjectivity of all war reporting and reminds us that photography, so often considered the gold standard for eyewitness documentation, was only one means of expression chosen by artists addressing the raw facts and messy consequences of war.”

The exhibition is organized chronologically and includes the following sections:

Early Modern Battles and Military Strategy

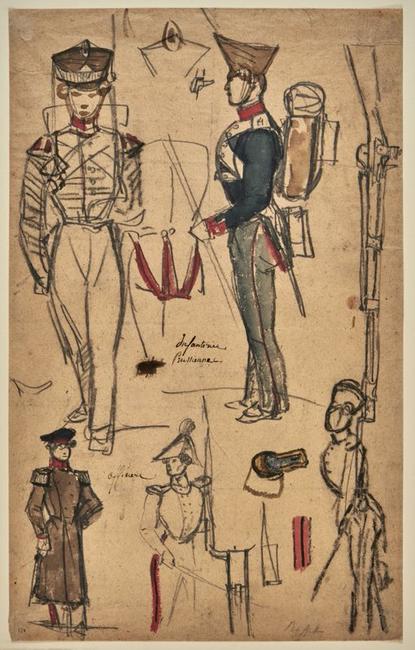

Much war imagery from 1500–1800 lacks an eyewitness dimension. Renaissance artists were often attracted to staged, reconfigured, or imagined battle subjects for the compositional challenge of arranging large groups of figures and rendering the human body in strenuous action. Major artists were also involved in designs for military fortifications and defense, on commission from their princely leaders. The difference is palpable, for example, between Albrecht Dürer’s diagrammatic Siege of a Fortress prints (1527), made as a theoretical demonstration of the efficacy of a fortification design, and two battle drawings (1793-94) made by Nicolas Antoine Taunay based on his observation of contemporary events.

The Age of Napoleon

The relentlessly ambitious French general Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) parlayed his legendary reputation as a military strategist into a ruthless quest for imperial domination within and beyond Europe. The suffering and destruction wrought by Napoleon’s military campaigns loom large in Francisco de Goya’s print series The Disasters of War. Subtitled “Fatal Consequences,” the album of eighty prints chronicles the horrors of the Peninsular War between Spain and France from 1808 to 1814, including atrocities committed against civilians and a terrible famine in Madrid. The very rare bound album of Goya’s print series is included in the exhibition, showing one page of the portfolio, while a full presentation of all eighty works is featured on-screen in the gallery and on the exhibition microsite at clarkart.edu/astheysawit.

The Crimean War

The Crimean War, which claimed an estimated 650,000 lives between 1853 and 1856, was the first major conflict in which photography played a significant documentary role. Named after the Crimean Peninsula on the Black Sea, the war was fought by an alliance between Britain, France, Turkey, and Sardinia against Russia. Religious tensions between Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox believers had spurred Russia’s Czar Nicholas I to take advantage of a weakened Ottoman Empire and try to expand his influence into the eastern Mediterranean region.

Photography in the field posed many risks and challenges that required ingenuity and quick thinking. Other technological “firsts” from the Crimean War included explosive naval shells, railways, and telegraphs. These innovations revolutionized not just how war was waged but also how it was reported. With communication accelerated by mechanical means, the potential grew for people distant from the front lines to experience a more immediate sense of conflicts far away.

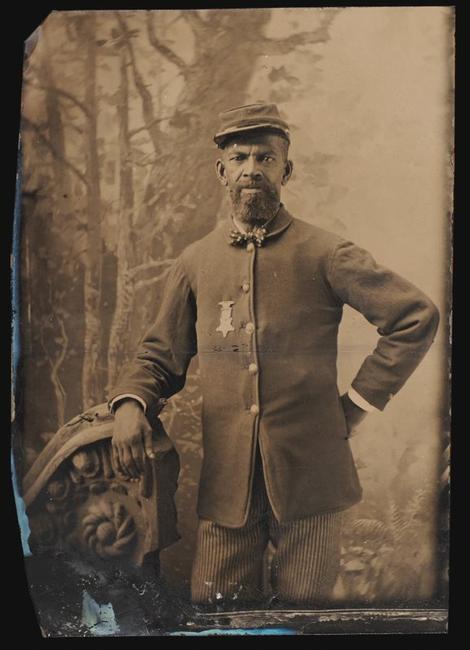

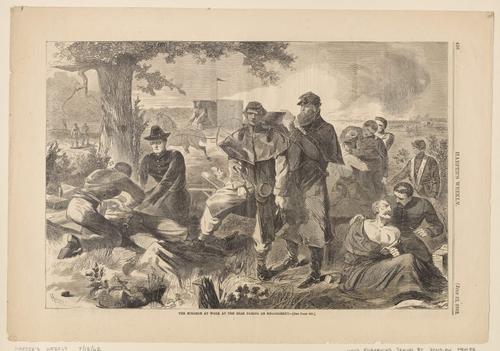

The American Civil War

Alongside wood-engraved illustrations, photography emerged as an essential reporting tool during the American Civil War. Mathew Brady was an early figure in what came to be known as photojournalism. His studio dispatched many field photographers, equipped with portable darkrooms, to capture the immediacy and atrocity of battle. Yet the history of documenting the Civil War cannot be summed up easily, given the anonymity of many photographers and the many pictured soldiers whose names are likewise unknown. Although insufficiently recognized in the historical record, more than 200,000 Black Americans served in the Civil War in the United States. The United States Colored Troops—army regiments comprising African Americans and members of other minority groups—were supplemented by thousands more who served in the Navy and segregated state regiments. The Clark’s works-on-paper collection has recently been enhanced by several new acquisitions that document Black soldiers’ essential contributions to the Union victory; these recent additions are featured in the exhibition.

The Siege of Paris, 1871

France’s war with Prussia (Germany) in 1870 was expected to score a quick victory for Emperor Napoleon III, but instead it led to the disastrous Siege of Paris and great suffering among the civilian population. During the siege, hunger and disease ran rampant, while routine shelling tore apart the fabric of the city. The emperor’s abdication in 1871 ushered in a tumultuous period of civil unrest and street violence known as the Paris Commune, in which an estimated 30,000 people died. Although some artists fled Paris during the strife, others, including Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, remained. Manet’s lithograph of The Barricade (1871) records the shooting of socialist Communards by French army troops, in an echo of the firing squad in his earlier composition The Execution of Maximilian (1867).

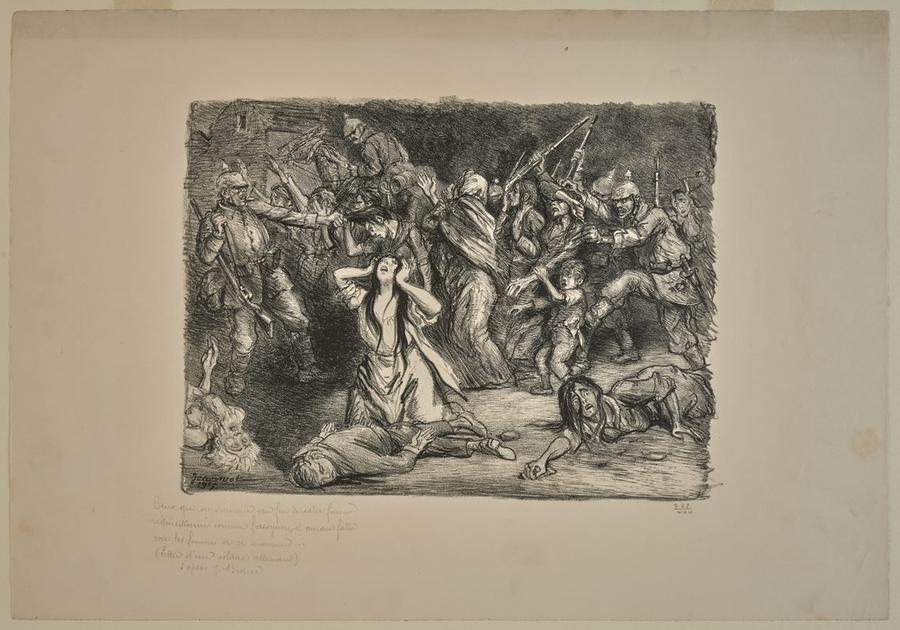

World War I

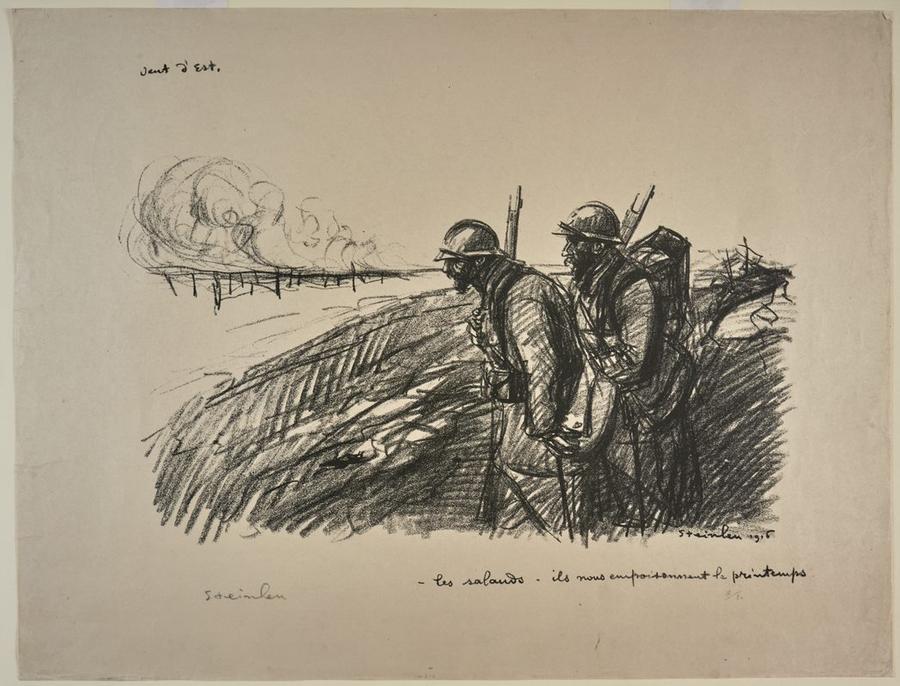

World War I was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history, with an estimated total of 40 million casualties. A series of lithographs by Georges Jeanniot (c. 1915–1916) present a searing representation of individual confrontations, both on and off the battlefield. World War I has a disproportionate representation in the Clark’s collection, perhaps stemming from museum founder Sterling Clark’s own experiences in the war. Having served a prior tour in Asia as an army volunteer just out of college (1899–1905), Clark was living in Paris with his wife, Francine, when the United States entered World War I in 1917. He rejoined the military at the rank of major in the Inspector-General Corps, serving as a liaison officer between the American and French forces until 1919.

The exhibition is organized by the Clark Art Institute and curated by Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.