June 25 to November 6, 2022

This summer, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA) in Brunswick, Maine, will present At First Light: Two Centuries of Artists in Maine, an expansive exploration of how artists have shaped our understanding—and often, quite literally how we see—Maine’s landscapes, communities, and people. At First Light will include more than 100 works, including those by such historic acclaimed artists such as Berenice Abbott, Lynne Drexler, Marsden Hartley, Winslow Homer, and Andrew Wyeth, as well as living masters Katherine Bradford, Barry Dana, Lois Dodd, Daniel Minter, Richard Tuttle, and William Wegman, to name just a few of the numerous artists whose artistic production has been nurtured in Maine over the course of two centuries.

Together the featured works, which range widely in media, style, and approach, will offer a vivid portrait of Maine while charting its relationship to wider artistic developments in American art. At First Light will be on view from June 25 to November 6, 2022.

While this exhibition was originally scheduled to coincide with the bicentennial of Maine statehood in 2020, the concept behind this exhibition has evolved as much as the surrounding world has changed. Over the last decade, BCMA has been steadily diversifying its collections, in particular emphasizing an expanded perspective on American art. As Maine moves beyond its bicentennial, this presented an opportunity to re-evaluate how At First Light could better reflect this diversity of art and artists working in Maine—and to acknowledge more clearly some of its challenging histories. In some cases, that means more deeply examining the experiences of artists of color, in particular those from the Native American and Black communities; in other cases, the addition of other artworks explores more directly the tension between appreciation for the state’s natural beauty and the history of resource extraction. At the same time, three artists who were expected to be vibrant participants in the exhibition when it opened—Ashley Bryan, David Driskell, and Molly Neptune Parker—have since passed away. The exhibition will explore their significant role and impact on the arts of Maine.

In tandem with At First Light, the Bowdoin Museum will be presenting two additional exhibitions that—in different ways—also underscore Maine’s long history as a home to artists. The first of these companion shows, At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes, and Studios, an installation of photographs by Walter Smalling, the celebrated architectural photographer, who has produced a photographic record of the homes, studios, and favored locations of 26 artists who lived and worked in Maine, from the early 19th century to the present. The installation of Smalling’s work also opens on May 26. The second exhibition is Innovation and Resilience Across Three Generations of Wabanaki Basket-Making, which highlights the dynamic tradition of basket-making and features the unique styles and designs of Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Micmac artists. Curated by members of Bowdoin’s Native American Students Association, the show brings historical baskets together with some of the finest examples of contemporary Wabanaki artistry. This exhibition, which opened on February 1, is being extended through September 18, so that its presentation runs in tandem with At First Light.

“To look at Maine’s artistic history is also to explore the trajectory of American art more broadly,” said Frank Goodyear, Co-Director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. “Through the more than 100 works featured in At First Light, we will capture the developments and evolutions within creative practice and across an array of communities, with a show that will fully engage our audiences in seeing the vibrant exploration of Maine’s artistic traditions and its present-day creative spirit.” Added Anne Collins Goodyear, Co-Director of the Museum, “We deeply mourn the loss of Ashley Bryan, David Driskell, and Molly Neptune Parker, whose art and personal histories were sources of inspiration. Although this exhibition

extends well beyond their work, theirs are foundational pieces for this exhibition, a means of connecting with the challenges of the last two years even as our community, our state, and our nation look to the future.”

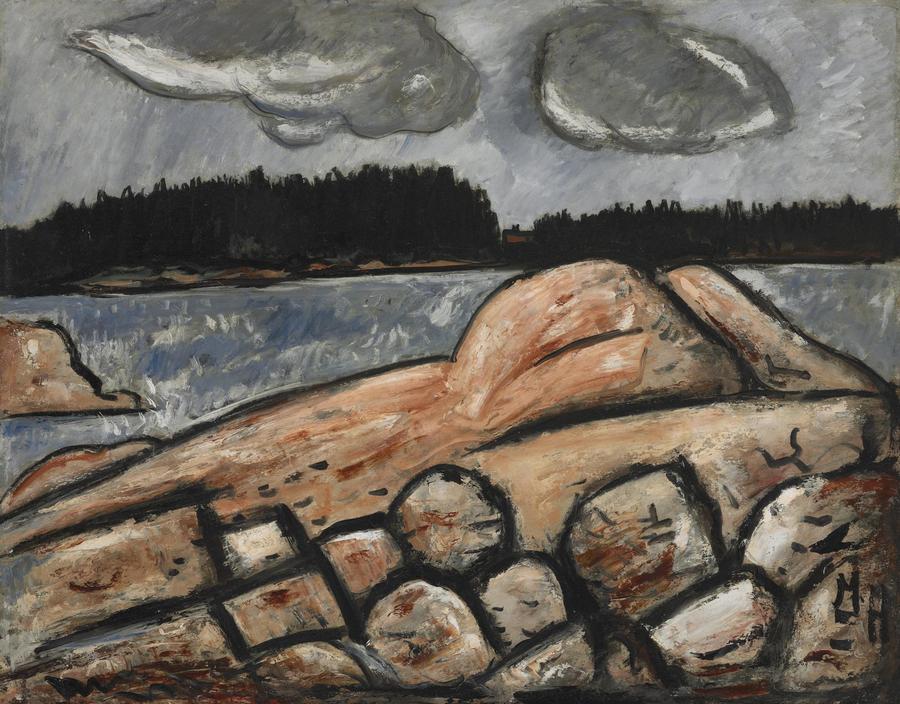

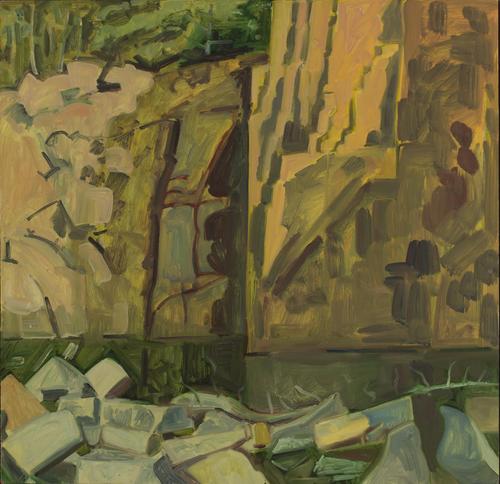

At First Light will be installed chronologically, allowing audiences to experience how ideas were communicated to different artists and communities through evolving artistic styles and approaches. Among the underlying themes is Maine’s dramatic landscapes, which will examined through works such as Thomas Cole’s House, Mount Desert, Maine (1844-45), Winslow Homer’s Sunlight on the Coast (1890), George Bellow’s Green Breaker (1913), Marsden Hartley’s After the Storm, Vinalhaven (1938-39), Ashley Bryan’s Spruce, Soli Deo Gloria (Skowhegan), (c. 1950), Lois Dodd’s Long Cove Quarry (1993), and Abelardo Morell’s Rock and Snow (2015). Other works will evoke the professional occupations that have come to characterize Maine and drive its economy, from tourism, as experienced in Wegman’s playful works, to the traditional industries of logging, as depicted by George Hawley Hallowell and Berenice Abbott, and lobstering, as seen through the work of Olive Pierce and Andrew Wyeth.

The presence and impact of growing communities of ambitious artists over the course of two centuries are also examined throughout the exhibition—and artists have been adept at capturing and expressing the character and diversity of Mainers themselves. This can be seen in Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of the abolitionist Phebe Lord Upham (ca. 1823) and in Jeremiah Pearson’s depiction of the African American barber Abraham Hanson (ca. 1828). Marguerite Zorach’s The Family Evening (ca. 1924) testifies to the formation of communities of artists in the region, which began to proliferate in the early 20th century, as areas such as Ogunquit, Georgetown, Monhegan, Skowhegan, Mt. Desert Island, Vinalhaven, and the Rangely Lakes became more accessible to creative practitioners eager to escape urban settings.

The exhibition will also explore the work of many of Maine’s native artists, including members of the Wabanaki Confederacy through the work of Barry Dana, Molly Neptune Parker, and the Ambroise St. Aubin Family. These three artists will all be featured in At First Light; Parker, along with her grandson Geo Neptune, will also be featured in Innovation and Resilience. Addressing the formation of artistic communities across the state, the exhibition will draw connections between artists and their creative motivations, offering a range of artistic voices including those that are well known—and many others are not.

Another approach to measuring the impact of Maine on centuries of artists is through the lens of where these artists’ art was collected. In addition to the many masterpieces in At First Light drawn from the BCMA’s collection, the exhibition is supported by important loans from other institutions, including the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Farnsworth Art Museum, the Harvard Art Museum, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, and the Toledo Museum of Art.

Among the artists included in Smalling’s series of photos for At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes, and Studios, are Bryan, Dodd, Driskell, Hartley, Homer, Robert Indiana, Alex Katz, Rockwell Kent, John Marin, Parker Fairfield Porter, the Wyeths, and Marguerite and William Zorach.

Smalling’s photos are also available as a book published by Rizzoli Electa that brings these photographs together with images of notable works by each of the featured artists, as well as texts by the BCMA’s co-directors, along with Michael Komanecky, Chief Curator at the Farnsworth Art Museum. Stuart Kestenbaum, the poet laureate of Maine, has contributed a forward.

In Innovation and Resilience Across Three Generations of Wabanaki Basket-Making, audiences can explore the many connections between these Indigenous Maine communities and this traditional art form. While the Wabanaki have been weaving baskets since time immemorial, when they were forced off their land under European colonization, basket-making became a means of economic independence and resistance to assimilation. Since the nineteenth century, Wabanaki artists innovated traditional utilitarian forms to meet collectors’ tastes, leading to a new style of basketmaking—fancy baskets. The art form remains a powerful avenue for individual artistic expression and a vehicle for sharing generational knowledge. In the recent past, artists such as Geo Neptune, Molly Neptune Parker H’15, Clara Neptune Keezer, and Fred Tomah have influenced other aspiring basket-makers, shaping the path of Wabanaki basket-making traditions for generations to come. In addition, Wabanaki basket-makers have partnered with natural resource managers and forestry scientists to create the Ash Task Force, which works to combat an invasive beetle called the emerald ash borer, which threatens the future of Wabanaki baskets’ primary material, brown ash. The exhibition was curated by Amanda Cassano ’22, Sunshine Eaton ’22, and Shandiin Largo ’23, all members of the Native American Students Association. Assistance with translations was provided by Dwayne Tomah, a member of the Passamaquoddy Nation.