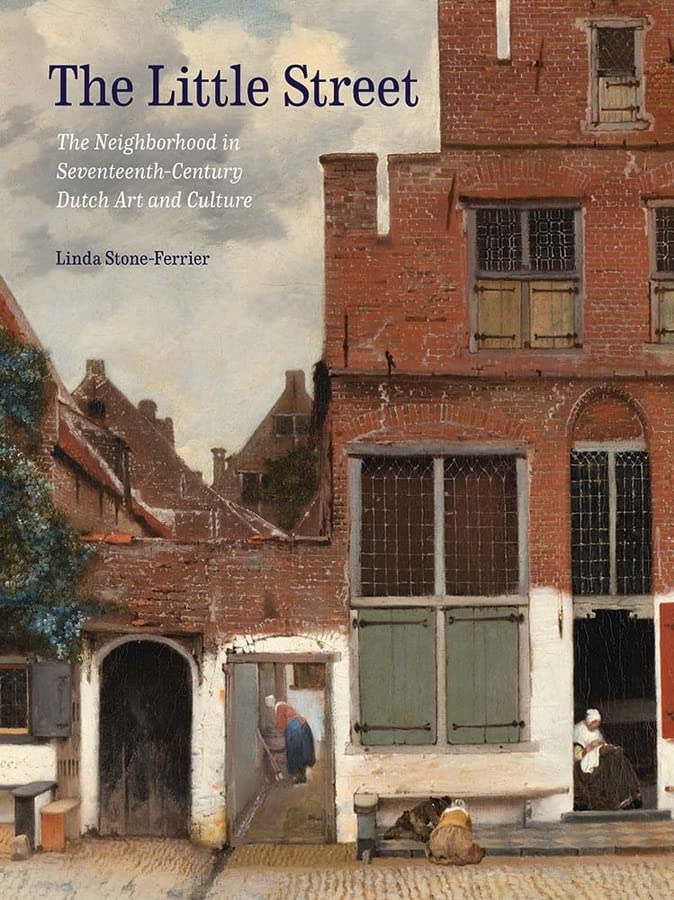

That is Linda Stone-Ferrier’s conclusion after analyzing a range of 17th-century Dutch paintings in a new context: that of the neighborhood. Her book, “The Little Street: The Neighborhood in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and Culture,” is just out from Yale University Press after a 14-year process of research, writing and editing.

A professor of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art in KU’s Kress Foundation Department of Art History, Stone-Ferrier realized she would begin research for a book like “The Little Street” when, by chance, she read an article about 17th-century Netherlandish neighborhoods by the sociologist Herman Roodenburg.

“I knew no art historian had ever talked about the neighborhood, which Roodenburg made very clear was a significant organizing unit for social control and social exchange,” Stone-Ferrier said. “No art historians of Dutch art had ever addressed the neighborhood as an interpretive context for the study of Dutch paintings.”

In the book’s introduction, she writes that studies by art historians tend to silo works by subject matter, like landscapes or scenes of daily life, “presum(ing) that each category raises interpretive issues distinct from the others. In a revision of that paradigm, I argue that certain seemingly diverse subjects share the neighborhood as a meaningful context for analysis.”

In addition, Stone-Ferrier writes, her book challenges scholars’ assumptions that categorize “imagery in paintings within a binary construct of ‘private,’ understood as the female domestic sphere, versus ‘public,’ synonymous with the male domain of the city ...”

The neighborhood was a “liminal space” between home and city that encompassed people of every gender, religion, social class, nationality and political persuasion, she writes. In fact, Dutch citizens of the 1600s were required to officially belong to and participate in their neighborhood organizations – much like today’s homes associations – which collected membership dues, enforced neighborhood rules, and hosted mandatory meetings and annual group meals. Thanks to some exquisite recordkeeping from centuries ago and today’s digital resources, Stone-Ferrier was able to research, among other things, relevant subjects of paintings and the identity and professions of Dutch citizenry who owned them that informed her research. Art collecting was important, Stone-Ferrier said, to a broad and deep urban middle class whose wealth was generated by such trading enterprises as the Dutch East and West India companies.

And it's clear, from an analysis of that art and an array of documents, that what was going on down the street and around the corner was important to Dutch people of that time – just as it is to people in neighborhoods around the world today.

“Honor is the word the Dutch used in in their neighborhood regulations and in other contexts, too,” Stone-Ferrier said. “Honor had to do with how one behaved. To act honorably in all endeavors -- personally, at home, in your business -- was valued highly. An individual's honor or dishonor reflected on that of the whole neighborhood. That was an integral tie. That's why there was gossip and documented witness statements regarding the behavior of one’s neighbors.”

One chapter is subtitled “Glimpses, Glances, and Gossip” because — like today -- not only are people curious about what the neighbor across the street is doing in his driveway, or what is going on with those Rottweilers around the corner, but they want to make sure people are not misbehaving or breaking communal rules.

Paintings showing scenes of people upholding neighborhood virtues both reflected and reinforced those values, Stone-Ferrier writes.