Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

February 10 to May 28, 2023

In the 25 years of activity covered by the exhibition, there is a constant flow of new ideas ranging from his initial magic realism to his language of constellated signs.

In this period, it becomes clear that prehistoric art held a special interest for Miró, who proposed returning to the dawn of art in order to retrieve its original spiritual sense.

Admired for his formal innovations developed in the context of the first avant-garde movements, especially Dadaism and Surrealism, Miró is also considered a precursor of Abstract Expressionism and Conceptual Art.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao presents Joan Miró. Absolute Reality. Paris, 1920–1945, an exhibition that explores the career between the years 1920 and 1945 of one of the most outstanding artists of the 20th century. The start of this fundamental period in Miró’s oeuvre is marked by the date of his first trip to Paris, a key city in his life and work, and it closes with the year when Miró, after producing his Constellations (1940–41) and then hardly painting at all for some years, created a great series of works on white backgrounds that consolidated his language of signs floating on ambiguous grounds.

In the 25 years of activity covered by the exhibition, there is a constant flow of new ideas ranging from his initial magic realism to his language of constellated signs. In this development, it becomes clear that prehistoric art, including rock paintings, petroglyphs, and statuettes, held a special interest for Miró, a fascination confirmed by his notebooks, where he proposes returning to the dawn of art in order to retrieve its original spiritual sense.

The work of Joan Miró (b. 1893 Barcelona; d. 1983, Palma) is admired for its formal innovations developed in the context of the first avant-garde movements, especially Dadaism and Surrealism, and he is also considered a precursor of Abstract Expressionism. Miró was moreover an artist interested in spiritual matters and fascinated by visions and dreams. More recently, attention has also been drawn to the political aspects of his work, emphasizing his firm opposition to Franco’s dictatorship and his sympathy for the Catalan nationalism of the period. Some of his ideas like his proclamation of the “assassination of painting,” made at a point in the late 1920s when Miró was painting unceasingly, remain intriguing, and point to an attitude heralding Conceptual Art. Forty years after his death, in short, his oeuvre still interests and fascinates us while remaining just as enigmatic as ever.

Miró’s oeuvre is an exemplary mythopoetic project, a constant transformation of lived experience into art. As firmly as he ignored traditional realism, Miró also rejected the idea of pure abstraction, asserting that all the marks he painted on his works corresponded to something concrete and anchored in a profound reality that is part of reality itself. This idea relates to a phrase by poet André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement, who spoke of a new absolute reality in which the inner world of artists and poets was incorporated to the outside world. In the meantime, Paul Klee, an artist admired by Miró, called his own work abstract but with memories, meaning that in art, the real is the real transformed by memory. In statements made to Cahiers d’Art in 1939, Miró affirmed: “If we don’t try to discover the religious essence or the magical sense of things, we shall do no more than add new causes of degradation to those already surrounding people today.”

TOUR OF THE EXHIBITION

Miró spent his formative years in Barcelona at a time when nationalist sentiments were blooming. The Catalan capital was then a conservative city, but various outstanding personalities emerged there in the late 1910s with a commitment to the new ideas arriving from Paris, among them the composer Frederic Mompou, the poet J.V. Foix, and Miró himself. During World War I, several significant avant-garde artists also took refuge in Barcelona, such as Francis Picabia, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, and Marcel Duchamp, all of whom Miró met.

At that stage, the Catalan painter already longed to travel to the French capital, and he and his friends would discuss the news that arrived from it. He imagined that he would find great creative freedom in Paris and would frequent the company of the most advanced artists, poets, and art dealers of his time, as was indeed to occur.

1918–1920

In 1918–1920, Miró painted what have been called his “detailist” works, characterized by great concentration and delicacy of execution. In them, the leaves of trees and plants look like minutely exact calligraphies, reminiscent of oriental artistic practices. The rural world in these early works becomes an Arcadian setting. Rather than representing reality precisely, Miró paints the emotions the landscapes arouse in him. The desire for objectivity is transformed into a visionary gaze.

Also from this first period is Self-portrait (1919), which still manifests a desire for objectivity related to visible reality. It is a long way from two later self-portraits, Self-portrait I (1937–38) and Self-portrait II (1938). In the first, Miró turns himself into a transparent figure and his eyes and the buttonholes of his shirt adopt astral or cosmic forms, while his face is the emblem of his inner world. In the second self-portrait of 1938, Miró transforms himself literally into the night, for this is a pure vision of himself at a moment of rapture. In this work, two red circles surrounded by tongues of yellow flame float in a black space with no limits or horizon, while all around are stars, fishes, birds, butterflies, and biomorphic abstract shapes. The whole thing suggests ecstasy.

For Margit Rowell, “Miró’s spiritual life, his inner landscape, was as real to him as the sun, an insect, or a blade of grass. (…) His mythopoetic conscience seldom saw reality without a filter: the filter that transformed any truth into an Absolute Truth.”

Early 1920s

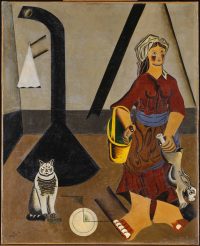

Miró wrote to his friend J.F. Ràfols in 1923 on the subject of the new landscapes he was then painting: “I have managed definitively to break away and free myself from nature, and the landscapes no longer have anything to do with external reality,” the goal being “greater emotional power.” Interior (The Farmer’s Wife, 1922–23), another painting of the rural world, is also a transitional work. To paint the farmer’s wife of the title, Miró used a doll, which heightens a final sensation of strangeness. In this picture, all the visible elements, including a cat and a stove, can still be clearly identified. However, the woman’s enormous bare feet confirm that mere representation is not the painter’s objective here, and that the energy which transfigures the real comes from the earth.

In his first Paris studio at 45, Rue Blomet, which he occupied in 1921, Miró painted the landscapes which bear no reference to external reality. André Masson was a neighbor of his, and among the outstanding artists and poets who passed through Miró’s studio were Antonin Artaud, Raymond Roussel, Robert Desnos, Paul Eluard, Michel Leiris, Benjamin Péret and René Char. He was interested in the formal innovations of all these figures, who rejected logic, cliché, and tradition while turning their attention to questions like automatism, the aesthetics of fragmentation, the arbitrary union of unexpected and unconnected images, and the visual and typographical use of poetic texts in calligrams. Miró’s pictures of the mid–1920s, known as the dream paintings, destroy any logical narrative structure, and the few elements that appear scattered over their surfaces appear to be the result of improvisation, although his sketches prove the opposite.

Rue Tourlaque

Between 1926-1927, Miró changed studio and style. He moved to the Rue Tourlaque, where he worked until 1929, alternating with summers in Catalonia, and where he frequented the company of artists like Jean Arp, René Magritte, and Max Ernst, his new neighbors. Among his most outstanding works of that time are various large-format horizontal landscapes like Landscape (Landscape with Rooster) and Landscape (The Hare), both of 1927. Here, Miró paints certain recognizable but stylized elements. The intensely colored backgrounds of these pictures suggest wide open spaces, while traditional procedures like shading, the construction of volume, and perspective all disappear. In 1927, Miró also produced a series of small paintings on white backgrounds like Painting (The Sun) and Painting (The Star). In these works, the background is a pure pictorial space where recognizable but stylized forms of stars and animals float like emblems of this new reality.

The 1930s

In the 1930s, expressionism became a dominant characteristic of Miró’s work. This is the case of Group of Personnages in the Forest (1931), the so-called Wild Paintings (1934–38), a series of paintings on sandpaper, collages, small paintings on copper like Man and Woman in front of a Pile of Excrement (1935), an extensive series of paintings on masonite from the summer of 1936, and another on celotex of 1937. In general, all of them are characterized by displaying monstrous figures in ambiguous and disturbing settings, probably a reflection of his worry and anxiety over the political situation that led to the Spanish Civil War and World War II. Miró created the 27 paintings on masonite panels of the same size during the summer that brought the start of the Civil War. These works anticipate the Action Painting of the New York School, where the act of painting becomes the subject of the work. His images are an illustration of the process that has given rise to them. Miró paints on a highly textured material with an intense earthy color upon which he rapidly superimposes black strokes and fields of color, employing other richly textured materials like tar, gravel, or sand. Sometimes he scrapes or pierces the surface. In spite of their spontaneity, certain forms in these works are recognizable or suggestive of specific things, such as eyes, heads, and phalluses.

Varengeville-sur-Mer

With the start of World War II, Miró, who was exiled in Paris, moved to a small house in Varengeville-sur- Mer in Normandy, where he received a commission to paint a mural. Once there, he painted five small landscapes entitled The Flight of a Bird over the Plain, a reference to the open plains of that area and the crows flying over them. It was a very different landscape to that of the Mediterranean.

From Varengeville, Miró wrote to his friend Roland Penrose about the way the Constellations had arisen: “After painting, I dipped my brushes in turpentine and dried them on white sheets of paper, without following preconceived ideas. The stained surface stimulated me and led to the birth of forms, human figures, animals, stars, the sky, the sun, and the moon. I drew all these things vigorously with charcoal.

Once I had achieved a balance in the composition and had put all these elements in order, I started to

paint with gouache, with the minuteness of a craftsman or a primitive man; this took me a long time.”

The 23 constellations were painted between January 1940 and September 1941. They were finished in Majorca, where Miró and his family took up residence after fleeing from the war in France. When they were shown at Pierre Matisse’s gallery in New York in 1945, they were the first works created during the war to be exhibited in the United States, and they made a great impact. These paintings are the culmination of the potential of the language of signs created by Miró, with an emphasis on imagination and intuition, and a desire to find a primal and universal form of expression.

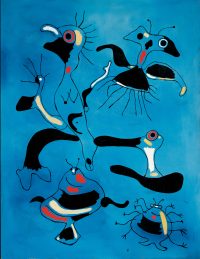

After the Constellations, Miró shut himself up in Majorca with his family and stopped painting for a time. Things changed in 1945, when he produced a great series of large-format paintings, once more on a white background, in which he resumed the development of his language of signs. Woman and Birds in the Night, Figure and Birds in the Night, and Woman in the Night are among the titles of this series, some of which are repeated. Nearly all the works have the word ‘night’ in their title, although the backgrounds are white and luminous. From 1944 on, Miró also took an interest in ceramics, working in partnership with Josep Llorens i Artigas.

Images

Joan Miró

Autorretrato, 1919

Óleo sobre lienzo

73 x 60 cm

Musée national Picasso – París. Donación Picasso, 1978. MP2017-28

© Successió Miró, 2023

Fotografía : © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso-Paris) /Mathieu Rabeau

Joan Miró

Interior (La masovera) [Intérieur (La Fermière)], 1922-23

Óleo sobre lienzo

81 x 65 cm

Centre Georges Pompidou, París. Musée national d'art moderne/Centre de Creation Industrielle, Dación 1997

© Successió Miró, 2023

Fotografía: © RMN-Grand Palais/Jean-François Tomasian

Joan Miró

El gentleman (Le Gentleman), 1924

Óleo sobre lienzo

52,5 x 46,5 cm

Kunstmuseum Basel-Schenkung Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, 1968

© Successió Miró, 2023

Fotografía: Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler

Joan Miró

Campesino catalán con guitarra (Paysan catalan à la guitare), 1924

Óleo sobre lienzo

147 x 114 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© Successió Miró, 2023

Fotografía: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Joan Miró

Pintura (Peinture), 1925

Óleo sobre lienzo

146 x 114,3 cm

Cortesía The David & Ezra Nahmad Collection

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

El saltamontes (La Sauterelle), 1926

Óleo sobre lienzo

114 x 147 cm

Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation, Atenas

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

Paisaje (La liebre) [Paysage (Le Lièvre)], Otoño, 1927

Óleo sobre lienzo

129,6 x 194,6 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Nueva York

57.1459

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

Pintura (Personaje: los hermanos Fratellini) [Peinture (Personnage: Les Frères Fratellini)], 1927

Óleo sobre lienzo

130 x 97,5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

Pintura (Pájaros) [Peinture (Oiseaux)], 1927

Óleo sobre lienzo

130 x 97 cm

Cortesía The David & Ezra Nahmad Collection

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

Pintura (El sol) [Peinture (Le Soleil)],1927

Óleo sobre lienzo

38,3 x 46,2 cm

Cortesía The David & Ezra Nahmad Collection

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

Pintura (Peinture), 1934

Óleo sobre lienzo

97 x 130 cm

Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. Donación: Joan Prats

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

El canto de los pájaros en otoño (Le Chant des oiseaux à l'automne), Septiembre 1937

Óleo sobre celotex

212 x 91 cm

Coleção de Arte Contemporânea do Estado, en préstamo a largo plazo a la Fundaçâo de Serralves - Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Oporto

© Successió Miró, 2023

Fotografía: © Filipe Braga

Joan Miró

Pintura-poema (Una estrella acaricia el seno de una negra) [Peinture-poème (Une étoile caresse le sein d'une négresse)],1938

Óleo sobre lienzo

129,5 x 194,3 cm

Tate: Adquirida en 1983

© Successió Miró, 2023

Fotografía: © Tate/Tate Images

Joan Miró

Pintura (Pájaros e insectos) [Peinture (Oiseaux et insectes)], 1938

Óleo sobre lienzo

114 x 88 cm

Albertina, Viena – Sammlung Batliner

© Successió Miró, 2023

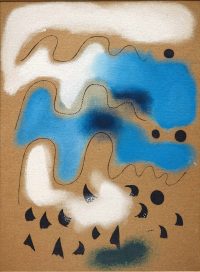

Joan Miró

Mujer y pájaros (Femme et oiseaux), 1940

Gouache y óleo sobre papel

38 x 46 cm

Cortesía The David & Ezra Nahmad Collection

© Successió Miró, 2023

Joan Miró

Mujer y pájaro en la noche (Femme et oiseau dans la nuit), 1945

Óleo sobre lienzo

146 x 114 cm

Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. Depósito de colección particular

© Successió Miró, 2023