Bozar, Centre for Fine Arts - Brussels

Beauty and Ugliness have always fascinated people, yet their meanings shift over time. From 20 February to 14 June 2026, Bozar presents Bellezza e Bruttezza, a historical exhibition that explores how artists from Italy and Northern Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries depicted these extremes. From refined ideals to deliberate caricatures. A rare opportunity to see extraordinary and precious works of Botticelli, Titian, Da Vinci, Tintoretto, Cranach the Elder, Matsys, and many others, displayed in Belgium for the first and only time.

The exhibition traces how the standards of Beauty and Ugliness evolved from the last quarter of the 15th century to the end of the 16th century—key transitional periods— by juxtaposing in a rich and compelling confrontation the ways in which these two subjects were interpreted by the greatest Italian artists and their counterparts from Northern Europe. Beauty became an increasingly important social concern at this time, as shown by the rising number of 16th-century publications offering “recipes for looking beautiful” and advice on cosmetics and care. Meanwhile, Ugliness also grew in prominence in art, appearing in a widening range of forms throughout the same period.

Over 90 exceptional works are on display at Bozar. The selection includes works by renowned artists such as Sandro Botticelli, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Leonardo da Vinci, Frans Floris de Vriendt, Albrecht Dürer, Lorenzo Lotto, Quentin Metsys,Titian, Tintoretto, Carracci, Bordone, Sellaer, Dürer, Veronese, Campi, Dossi...

The exhibition brings together these precious works from public and private collections across Europe and the United States. The prestigious lenders include: the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, Museo Nazionale Romano in Rome, the Vatican Museum, the Louvre, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Galleria Borghese in Rome and the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice.

Since ancient times, beauty and ugliness have been subjects that continue to fascinate and raise questions, as they are universal themes whose variations are determined by culture and era. How was the dialectic between beauty and ugliness formally expressed between the end of the 15th century and the 16th century, a period that would prove to be pivotal? Renaissance artists were the first to accord equal importance to both, and this interest grew throughout the 16th century.

This book explores this trajectory, presenting the themes of beauty and ugliness in their most salient and representative aspects. A comparative approach between the works of the Italian Renaissance and those of Northern Europe, particularly the former Netherlands, allows us to grasp the constants and variations in the history of forms and taste, supported by works accompanied by notes, including those by Sandro Botticelli, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Leonardo da Vinci, Frans Floris de Vriendt, Albrecht Dürer, Lorenzo Lotto, Quentin Metsys, Michelangelo, Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese.

Under the scientific direction of Chiara Rabbi Bernard, with essays by Cristina Acidini, Christophe Brouard, Elena Capretti, Maria Clelia Galassi, Yves Hersant, Koenraad Jonckheere, Catherine Lanoë, Pietro C. Marani and Giandomenico Spinola.

Quotes

Beauty and ugliness reinforce each other.

— Leonardo Da Vinci

The exhibition “Bellezza e Bruttezza” offers a new perspective on the dynamic tension between beauty and ugliness, exploring their most compelling expressions from the late fifteenth to the end of the sixteenth century—a pivotal moment in history.

— Chiara Rabbi Bernard, curator of the exhibition

“Bellezza e Bruttezza” reveals a nuanced vision of the Renaissance, inspired by the period’s understanding of the human being and the world. For Bozar, the exhibition is also a unique opportunity to unfold a multidisciplinary programme reflecting on contemporary perceptions of physical beauty.

— Christophe Slagmuylder, CEO & Artistic Director of Bozar – Centre of Fine Arts, Brussels

“This important exhibition - created especially for Bozar - brings together masterpieces of Renaissance art that seldom travel. It is a unique occasion to see these remarkable artworks in Brussels. The exhibition builds upon a long tradition of Bozar of presenting Old Masters. It explores an issue that has long motivated artists and raised great debate in society: what - and who is considered beautiful? And why? The exhibition highlights the continuity of Western standards of beauty. And the parallel exhibition of contemporary art – ‘Picture Perfect’ - attempts to unpick some of these norms from our 21st-century perspective."

— Zoë Gray, Director of Exhibitions, Bozar – Centre of Fine Arts, Brussels

Wall Texts

Introduction

In his treatise De Pictura (1435), Leon Battista Alberti tasked the painters of his day with the pursuit of beauty, which for him was based on a broad ideal of "elegant harmony", governed by mathematics. However, from the last quarter of the 15th century, artists started to show increasing attention to beauty’s opposite: ugliness. This phenomenon intensified throughout the 16th century, with representations of "divine heads" placed alongside ugly, even monstrous, ones. Why this unprecedented interest in representing the seemingly contradictory? Because beauty cannot exist without ugliness: they are inseparable, for one derives its meaning, and – perhaps even more so – its brilliance, from the other.

Beauty and ugliness have always been essential, universal themes, their variations in form and taste determined by cultures and eras. What better medium than art, with its power to condense images and create forms, to capture the sembianze (the "outward appearance") and restore their meaning, in an era when the cult and power of the image were not what they are today?

This exhibition seeks to highlight the most salient aspects of this confrontation between bellezza and bruttezza during the Renaissance, showing how they were represented by Italian and Northern European artists (particularly the Flemish), in the pivotal period from the last quarter of the 15th to the end of the 16th century.

Antiquity and the Renaissance

During the Renaissance, the representation of beauty and ugliness was largely influenced by Antiquity, as evidenced here by several striking examples. Initially, 15th- century artists remained largely indebted to the Ancients' conception of ideal beauty, understood as the harmonious association of parts with the whole. Starting with the study of real bodies to arrive at the representation of idealized human figures, they adopted "canonical" proportions and applied geometric grids for respecting certain mathematical relationships between the parts.

Ugliness, in Antiquity, was expressed more specifically by anything that deviated from these norms to come closer to real – sometimes visually unprepossessing – subjects. Certain portraits from Rome’s Republican era, for example, influenced several works by Renaissance artists. However, the discovery, in the 15th century, of the Roman frescoes of Nero's Domus Aurea would provide Renaissance artists with another idea of ugliness, a more imaginary one: that of the grotesques.

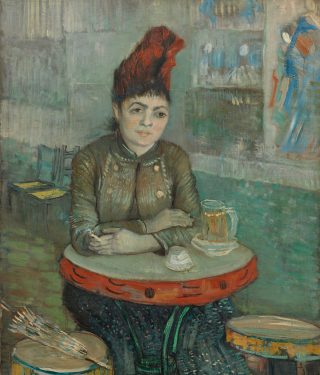

Beautiful Women and Realistic Portraiture in the Renaissance

Portraiture is undoubtedly the art form that best reveals how beauty and ugliness were interpreted and represented. The influence of Antiquity is evident in realistic portraits, inspired by the profiles that appeared on ancient coins and medals: the figures are hardly embellished, their flaws not erased. Ideal beauty, on the other hand, is most often depicted and expressed in feminine form, with a proliferation of beautiful, somewhat static-looking ladies. From the late 15th century, in imitation of Flemish art, the three-quarter profile became widespread, permitting a better definition of the subject's physiognomy and greater psychological precision; the posture too is less static. This resulted in a new representation of beauty and ugliness, which gained in complexity and individuality.

In Italian art, especially in the 16th century, the representation of beauty varied considerably depending on whether the artists were Venetian or Florentine: the former depicting beautiful women who come across as a sensuous and assertively seductive, the latter often portraying them as icy and distant.

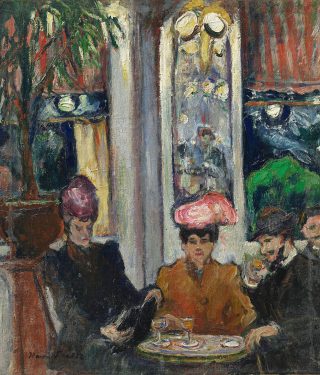

Muses, Monsters, and Prodigies

Renaissance artists also drew inspiration from real-life subjects who, because of their extreme appearance, were perceived as models that could be artistically idealised. This was the case of the very beautiful Simonetta Vespucci, one of whose supposed portraits is presented here. She inspired Botticelli in many works, including his famous Venus; her beauty was also celebrated by poets. The dwarf Morgante, by contrast, represented a certain model of ugliness, as did Madeleine Gonzales, who inherited from her father Pedro excessive hair growth due to a genetic anomaly, known as hypertrichosis. Those affected by this condition were considered monsters at the time. Such figures became genuine archetypes.

Beauty, Ugliness, and Artifice

In the 16th century, "artifice" referred to the technique of making a difficult-to- represent figure appear natural while simultaneously creating a more perfect form. Through such means, art could correct nature's flaws; but conversely, it could also distort nature, even rendering it monstrous. The widespread social practice of cosmetic art, common at the time, falls under the umbrella of artifice.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is grace, less acquired than bestowed, and with which even those considered naturally disproportionate can be endowed. Grace permits a transcending of traditional beauty, which was dependent on an external canon and the dogma of proportions and harmony; it also encompasses the inner dimension of being and confers a kind of nonchalant air, a sprezzatura, with both ethical and aesthetic connotations.

Making Oneself Beautiful

Reflections on beauty, and implicitly on ugliness, also manifested themselves during the 16th century with the publication and widespread dissemination of treatises and books of beauty recipes. In them we find the criteria for the ideal appearance of a woman: she should have particularly white skin, ample blond hair, dark eyes, rosy cheeks and red lips, a small nose, thin, arched eyebrows, a high, broad forehead, and well-proportioned limbs. The secrets of cosmetics to mask imperfections due to nature or illness were also revealed. While, like art, makeup aimed to perfect nature, often the opposite effect was achieved due to the harmful substances used in their preparations, which included materials such as lead, arsenic, or mercury.

Beautiful Ugliness: Caricatured Heads

It is impossible to find in nature, which is inherently varied, a model of beauty that is always identical and ideal. Moreover, Mannerist art freed itself from strict imitation. In a major shift, the artist felt more entitled to create ever-new forms. Norms, now perceived as unreliable, were transgressed.

Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer, from the last quarter of the 15th century onward, opted for a freer creation; distortion was not excluded, as evidenced by Da Vinci’s famous "caricate" (caricatured) heads. Ugliness and caricature acquired a new legitimacy, first in Italy and then in Northern Europe. These bodies and faces, which already disfigure the "normal" in some of the two masters' works, demonstrate that art does not shy away from arousing pleasure by resorting to monstrous figures. In this way, a "beautiful ugliness" is born.

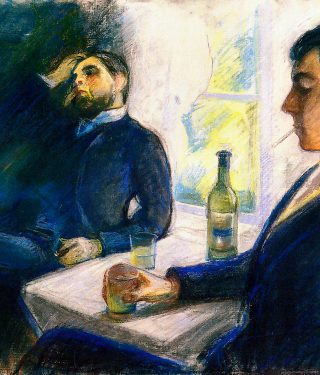

Villains, madmen, vicious or wicked persons... or the privileged figures of ugliness

During the 16th century, ugliness — also because of its protean nature — came to play an increasingly important role in Italian art and in that of Northern Europe, particularly in Flanders. Disproportionate bodies, deformities, and hybridizations: these singularities, which have an impact that is as much intellectual as visual, provided artists with rich sources of inspiration, enabling them to create captivating figures of ugliness. These figures are marked by a strong social and moral connotation, which the various sections of the exhibition seek to highlight.

It was easier for artists to distort the features of marginalized people, who were considered socially inferior, and often the artists sought to mock them, eliciting a laughter of superiority.

Comedy and Social Satire

“Certainly, there is nothing that gives more contentment and recreation than a

smiling face.”

Laurent Joubert (leading 16th-century French physician)

Fools and Jesters

“See with what foresight Nature, mother of humankind, has ensured that a pinch of folly is spread everywhere. [...] And so that human life might not be entirely sad and bitter, she has mixed in them more passions than reason.” Erasmus

Vices and Virtues

“Virtue, therefore, seems to be health, beauty, and well-being of the soul; and

vice, illness, ugliness, and weakness.”

Plato

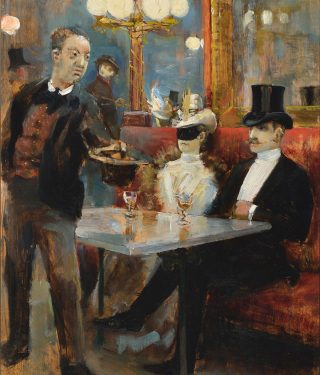

Beauty and Ugliness in Pairs

The association of beauty and ugliness is exemplified during the Renaissance by the pictorial genre of "unequal pairs": bellezza and bruttezza in one and the same work.

This theme, first illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, symbolically concludes the exhibition. Here, we encounter mythical mismatched couples from Antiquity, which served as inspiration for Renaissance artists. These are accompanied by secular couples from Italian art, engaged in games of seduction, and by couples from Northern Europe, whose relationship is based more on financial and moral considerations. At the end of the 16th century, we find a tendency to favour stark contrasts, the pairing of antithetical figures: a beautiful young woman alongside an old woman or an ugly old man, a handsome young man courting an ugly woman.

These couples further strengthen the conviction of Da Vinci that "beauty and ugliness reinforce each other".

Sandro Botticelli (toegeschreven aan / attribué à / attributed to) (Firenze, 1445 - Firenze, 1510)Allegorisch portret van een vrouw (Simonetta Vespucci?) / Portrait allégorique d'une femme (Simonetta Vespucci?) / Allegorical Portrait of a Woman (Simonetta Vespucci?)ca. 1490Tempera en olieverf op doek / Tempera et huile sur toile / Tempera and oil on canvas Privéverzameling / Collection privée / Private collection

Lucas Cranach de Oude / Lucas Cranach l’Ancien / Lucas Cranach the Elder (Kronach, 1472 - Weimar, 1553)Ongelijk liefdespaar (Jonge man en oude vrouw) / Le couple inégal (Jeune homme et vieille femme) / Ill-matched Couple (Young Man and Old Woman)ca. 1520-1522Olieverf op paneel / Huile sur panneau / Oil on panelBudapest, Szépművészeti Múzeum

Tiziano Vecellio, bekend als Titiaan / dit Titien / known as Titian

(Pieve di Cadore, 1488/90 - Venezia, 1576)

en atelier / et atelier / and workshop

Portret van Giulia Gonzaga / Portrait de Giulia Gonzaga / Portrait of Giulia Gonzaga ca. 1534Olieverf op doek / Huile sur toile / Oil on canvas Privéverzameling / Collection privée / Private collection

Tiziano Vecellio, bekend als Titiaan / dit Titien / known as Titian

(Pieve di Cadore, 1488/1490 - Venezia, 1576)

Vrouw met appel / Femme tenant une pomme / Woman Holding an Apple

ca. 1550-1555

Olieverf op doek / Huile sur toile / Oil on canvas

Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (Milano, 1538 - Milano, 1592) Grotesk hoofd van een vrouw in profiel / Tête grotesque de femme de profile / Grotesk Head of a Woman in Profile ca. 1560 Olieverf en tempera op paneel / Huile et tempera sur panneau / Oil and tempera on panel Privéverzameling / Collection privée / Private collection

Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem(Haarlem, 1562 - Haarlem, 1638)Portret van Pieter Cornelisz. van der Morsch als nar / Portrait de Pieter Cornelisz. van der Morsch en fou / Portrait of Pieter Cornelisz. van der Morsch as a Jester Eind 16e eeuw / Fin du XVIe siècle / End of the 16th centuryOlieverf op paneel / Huile sur panneau / Oil on panelAmsterdam, Allard Pierson, theatercollectie

Leonardo da Vinci / Léonard de Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) Grotesk hoofd van een vrouw in proel / Tête grotesque de femme de prole / Grotesk Head of a Woman in Prole ca. 1490-1500Pen, lichtbruine inkt en metaal- of zilverstift op papier / Plume et encre sépia claire, sur tracé à la pointe de plomb ou à la pointe d’argent / Pen and clear sepia ink with stylus or silverpoint on paperVenezia, Verzameling / Collection Ligabue

.TIF)